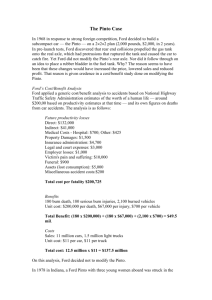

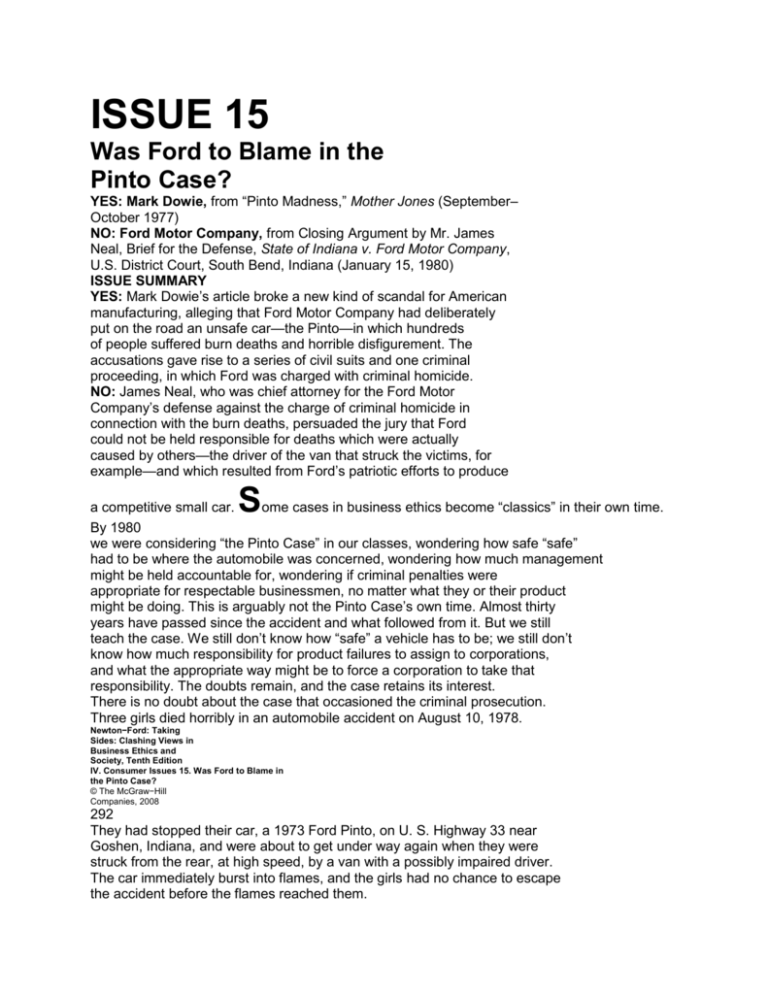

ISSUE 15 Was Ford to Blame in the Pinto Case?

advertisement