Diapositiva 1

advertisement

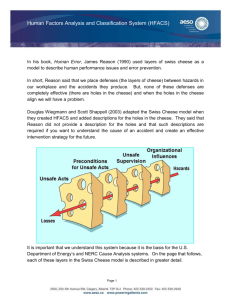

I. International Trade and development Raul Caruso Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano raul.caruso@unicatt.it 1 Let’s Start 2 The main question of this course is: Does trade help economic development? How? 3 World Trade and World Income 4 World Trade and World Income 5 World Trade and World Income 6 World Trade and Income 7 Trade and World Income 8 The question is still: Does Trade cause GDP growth? The answer seems to be YES 9 Trade and Income (Frankel and Romer 1999) 10 Frankel and Romer 1999 Frankel and Romer (1999) find that: (1) There is a positive effect of trade on income(economic factors). The levl of income is increasing in trade share (2) Increased size of the countries raises income. (geography matters) 11 Trade Share or Trade Openess Ratio Trade Openess Ratio The trade-to-GDP-ratio is the sum of exports and imports divided by GDP. This indicator measures a country's "openness" or "integration" in the world economy. It represents the combined weight of total trade in its economy, a measure of the degree of dependence of domestic producers on foreign markets and their trade orientation (for exports) and the degree of reliance of domestic demand on foreign supply of goods and services (for imports). Trade Openess Ratio X M GDP 12 For example consider these countries Trade/GDP 2004 Constant prices Australia Austria France Germany Italy Japan Poland UK USA Belgium 48,6 102,4 57,8 76,42 51,37 23,62 69,75 60,2 26,5 173,7 Source: OECD 13 Trade and Income, One more time… Harrison (2006) 14 However,…. Even if cross-country studies point to a positive relationship between globalization and overall growth, such growth may lead to unequal gains across different levels of income. If the growth effects on average are small trade-induced growth could be accompanied by a decline in incomes of the poor. 15 Trade and Poverty Harrison (2006) 16 Finally Therefore it seems that: There is an association between poverty reduction and trade. But aggregate studies sometimes are misleading 17 Main points or main questions? According to Harrison (2006) the evidence suggests that the poor are more likely to share in the gains from globalization when there are complementary policies in place: (1)investments in human capital and infrastructure; (2)policies to promote credit and technical assistance to farmers (3)policies to promote macroeconomic stability. (4)trade and foreign investment reforms have produced benefits for the poor in exporting sectors and sectors that receive foreign investment. (5)Financial crises are very costly to the poor. Finally, evidence suggests that globalization produces both 18 winners and losers among the poor. To continue…. Therefore, (1) Trade and development exhibit a complex association (2) Nowadays in 2010 in the aftermath of the global crises the picture could be completely different (3) We have first to go back to the basic economic theories of trade 19 Consider that USA is the largest country in the world with over the 21% of world income 17% of world imports and 10% of world exports 20 Basic Economics of Trade The Ricardian Model 21 Comparative Advantage Ricardo (1817) (1)A country(region) has a comparative advantage in producing a good (say clothing) if the opportunity cost of producing that good in terms of other goods is lower in that country than it is in other countries. (2)Eventually this country specializes in the production of clothing. (3)It will export clothing. 22 Assumptions of Ricardian World (1) There are 2 countries: Home and Foreign (2) Consider only two goods: cheese and wine (3) There is only one factor of production: Labor (4) Labor Productivity are constant 23 Some notations • The Home economy can be described by the following relation (see Krugman): • Where aLC Qc aLW QW L aLi , i c, w denote Unit Labour Requirements. In other words, they are coefficients capturing costs and technology of production. In this simplest case they denote how many hours are needed to produce a unit of a good. 24 More…. • Note also that the ratio: aLC aLW Can be defined as the opportunity cost of cheese in terms of wine. That is how many units of wine I have to give up in order to have 1 unit of cheese 25 For example….. • If aLC 1 aLW 2 This means that in order to have 1 extra unit of cheese I have to give up 1/2 units of wine. In one hour of work a person is supposed to produce 1 unit of cheese or ½ unit of wine. 26 Identifying Comparative Advantage • To have CA we must have: * LC * LW aLC a aLW a (1) That is, Home country has a comparative advantage in Cheese. 27 What about Prices? • Assume prices depending upon (1) cost ; (2) demand and supply. • In autarky the relative prices of goods equal their relative unit labour requirements: pc aLC pw aLW 28 What about Prices? • Note that if: pc aLC pw aLW The Economy will specialize in the production of cheese if the relative price of cheese exceeds its opportunity cost 29 Prices and CA • In the presence of CA we have: a*LC aLC pc * aLW pw a LW In the presence of trade the relative price of cheese must lie between the opportunity cost of cheese in terms of wine in Home and the opportunity cost of cheese in terms of wine in Foreign 30 Prices and CA • Consider the case: * aLC a LC pc * aLW a LW pw Both Home and Foreign will produce cheese. There will be no wine. The supply of cheese goes to infinity. 31 A numerical example of CA Unit Labor Requirements Home Foreign Cheese 1 6 Wine 2 3 See Krugman-Obstfeld, chap. 2 Note: Home has higher labor productivity in both industries In H the opportunity cost of producing cheese in terms of wine = ½ In F the opportunity cost of producing cheese in terms of wine =2 32 Production and Consumption in Autarky Units produced in Autarky Labor Supply=100, Cheese Wine Home 70 Foreign 11 World 81 15 10 25 33 A numerical example of CA Unit Labor Requirements Home Foreign Cheese 1 6 Wine 2 3 See Krugman-Obstfeld, chap. 2 Assume that in world equilibrium the relative price is Pc/Pw=1 Home will specialize in cheese production. Home workers can earn more by producing cheese 34 Production and Consumption with Trade Units produced in tre presence of Trade Labor Supply=100 Cheese Wine Home 100 Foreign 0 World 100 0 33 33 * L L YC ; YW* * aLC aLW 35 Production and Consumption with Trade • Consumption and Production Possibilities are higher in the presence of trade • Supply of both goods is larger 36 A trick? Note that in the example above we have: aLW a * LW That is, Home is more productive also in the production of wine, because it needs only two hours of work whilst Foreign country needs three (see the table). This is a case of Absolute Advantage Is it a Trick? NO. The CA theory suggests that each country specializes in the production of good in which it has the RELATIVELY lower unit labor requirements 37 Another Example Ham 200 100 Home Foreign aham 200 25 a peppers 8 a peppers aham 8 0.04 200 * aham 100 4 * a peppers 25 a*peppers * ham a 25 0.25 100 Peppers 8 25 * aham aham * a peppers a peppers a peppers aham a*peppers * aham 38 Another example (1) Foreign has CA in Ham (2) Home has CA in Peppers Foreign does specialise in Ham Home does specialise in Peppers 39 CA Theory’s Legacy • Productivity differences play a role in international trade • Comparative Advantage rather than Absolute advantage matters • Evidence confirms that countries tend to export goods in which they have relatively high productivity 40 Measuring Comparative Advantage • Belassa Index of Comparative Advantage X ijt / X wjt X ijt / X wjt bijt X it / X wt ED where – for every time period t considered – i denotes a specific country, w indicates the world economy (i.e. the entire set of countries considered in the analysis), and j is a specific sector. b is, therefore, a sectoral relative export measure in terms of share of world exports. Since the numerator ranges from 0 (the country is not exporting products belonging to that particular sector) to 1 (the country is an international monopolist in such category of products), and the denominator which is the economic dimension of the country, in export terms – also ranges from 0 to 1, then b ranges between 0 and ED. 41 Some Elaborations Source: De Benedictis (2005) 42 A very simple model to explain competitiveness • Consider only one factor of production: Labor. • This assumption holds in the short-run • The Unit labour cost is the key factor • The ULC can help us for a prediction of CA • Prices depend upon ULC 43 Notations Consider Employement =N Average Hours=AH Production = Y Labor Productivity= LP Wage = W Unit Labor Cost =ULC Exchange Rate = E 44 A very simple model You have N, Y, AH, W and E Then, The total hours worked (TH) are simply: TH=N*AH and the Labor Productivity (LP) is: LP=Y/TH 45 • Then, consider wages. [Note that differently from neoclassical predictions in many countries (ex. European contries) wages are sticky]. • The unit labour cost then is given by: ULC=W/LP • (1) when wages go up ULC goes up as well; (2) when LP goes up ULC goes down. 46 Identifying CA Then, consider the relation (1) and use ULC. It becomes: ULCC ULCC* ULCW ULCw* 47 A very simple model • To have a trend consider growth rates. Take Natural Logs of our variables. Then, we have: th n ah lp y th ulc w lp 48 Therefore… Therefore in the short run we easily find that prices depend upon ULC as: P ULC(1 K ) Where K denotes a mark up which in the shot run can be easily assumed to be constant [especially within industries]. Then we write simply that: P ULC 49 International Competitiveness To be sold on the world market goods have to be converted into an international currency. (say the $). P E ULC * Where E denotes the exchange rate between the home country and the american dollar assumed to be the international currency. Therefore P* is the international price of goods to be exported. Namely a key factor for international competitiveness 50 Taking natural logs we can easily compute the growth rate of ULC expressed in dollars. This is a good proxy for evaluating international competitiveness. p e ulc * Namely, the growth rate of international price of goods to be exported equals the sum of growth rate of exchange rate and the growth rate of ULC. That is, the international competitiveness depends upon (i) rate of change of exchange rate; (ii) change of productivity. 51 Labor Productivity and Unit labour costs Productivity and Unit Labour Costs in some OECD coutries growth rates 2000-2005 Productio Employe Average Hours n ment Italy -1,2 -0,2 -0.3 Germany 1,7 -1,5 -0,3 France 1,2 -1,8 -0,5 Sweden 3,9 -1,7 -0,2 USA 1,5 -3,7 0,1 Total Hours -0,6 -1,8 -2,3 -1,9 -0,3 Hourly Productiv Hourly ity Wages -0,6 3,1 3,5 2 3,6 3,2 5,9 4,3 5,8 4,6 Unit Labour exchange ULC in rate Costs dollars 3,7 6,2 10 -1,5 6,2 4,7 -0,4 6,2 5,8 -1,6 4,2 2,7 -1,1 // -1,1 Source: figures collected from Bureau of Labor Statistics 52 Productivity in OECD countries (growth rates) 53 EU-15 54 USA 55 56 Sweden 57 Poland 58