The Heavens Were Alive With Fire

advertisement

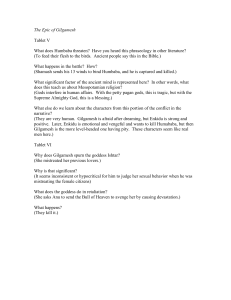

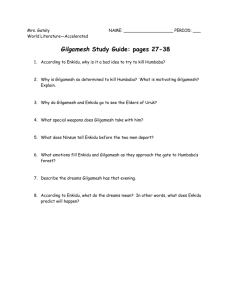

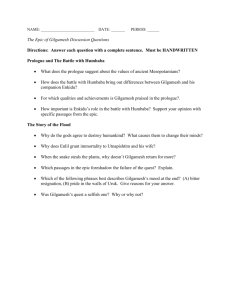

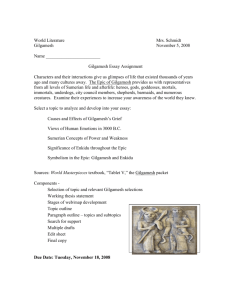

Gilgamesh: The Heavens Were Alive With Fire Feraco Myth to Science Fiction 19 September 2012 He tried to ask his friend for help Whom he had just encouraged to move on, But he could only stutter and hold out His paralyzed hand. It will pass, said Gilgamesh. Would you want to stay behind because of that? We must go down into the forest together. Forget your fear of death. I will go before you And protect you. Dreams take on great importance within the epic. They foreshadow the future, reinforce themes, and influence the characters’ decisions – even serving as Shamash’s conduit to Gilgamesh’s consciousness. Several of them are worth knowing and analyzing. I saw a star Fall from the sky, and the people Of Uruk stood around and admired it, And I was jealous and tried to carry it away But I was too weak and I failed. What does it mean? I have not dreamed Like this before. Ninsun tells him that the star represents “a companion who is your equal/In strength, a person loyal to a friend,/Who will not forsake you and whom you/Will never wish to leave.” Gilgamesh’s only objection to her interpretation: he has never failed before. The people stood around the ax When I tried to lift it, and I failed. I feel such tiredness. I cannot explain. Ninsun tells him the same thing – the ax symbolizes your “friend and equal” (who we know will be Enkidu). But her interpretations here don’t fit, or at least don’t tell the whole story. When it comes to lifting stars and axes – or at least their human counterparts – Gilgamesh actually can do it. After all, the two men journey to the Cedar Forest over Enkidu’s fevered opposition. Enkidu never agrees with Gilgamesh’s views: he simply gives in and goes along…much like a star or ax being carried somewhere (not moving of its own accord). The problem, of course, is that Gilgamesh often tries to possess whatever’s within reach – and he cannot control what he aims to carry here, because he is not the only force acting upon it. While the two visions are highly similar, I’d submit that the star-as-Enkidu parallel works more effectively; the ax, in my view, makes for a more problematic comparison. If anything, the ax seems to symbolize the forces that govern mortality (an ax, after all, could be used to cut a life in two) moreso than Enkidu. After all, Gilgamesh also tries to master these forces, and with plenty of people standing around (Utnapishtim, Siduri, Urshanabi, etc.). While he succeeds somewhat in influencing Enkidu, however, he ultimately fails to control life and death (with the relationship between both represented by Enkidu). If anything, then, Gilgamesh dreams of death at roughly the same time he dreams of that which gives him life – a somewhat unsettling image, but one that’s perfectly in keeping with the lesson the epic ultimately seeks to teach. After being urged in his dreams to kill Humbaba, Gilgamesh departs with Enkidu. He stops to receive Ninsun’s blessing and prayers, at which point she curses Shamash and welcomes Enkidu (ceremonially) into her family. But where Mason’s translation cuts a large (and hugely repetitive) section covering the heroes’ journey to the forest, that section is actually worth noticing. The passage of time in these ancient stories was often marked by refrains – intentionally repeated passages, like choruses in pop songs – and Gilgamesh’s author is no stranger to the technique Gilgamesh himself has no fewer than five dreams before he reaches the forest, always preceded by Enkidu performing the same ritual and introduced by the same five questions:“What happened? Did you touch me? Did a god pass by? What makes my skin creep? Why am I cold?” And as it so happens, he dreams of terrible things. In one dream, a mountain falls on them. Next, a mountain attacks him (he’s only saved by a friendly stranger’s intervention). In a third, tremendous storm brings rain and fire. In yet another, a beast combined from two others breathes fire at him (he’s saved by the same stranger – Enkidu takes this as a sign that the gods are watching over and protecting Gilgamesh) Finally, a bull shatters the ground it stands on, killing scores of men. Here, the dreams are more useful as structural support than they are for foreshadowing purposes (hmm…what could that bull dream be hinting at?). Every time the heroes advance x amount of distance, growing closer and closer to the forest, the dreams return in increasingly terrifying fashion. The effect is similar to the one experienced by horror-film audiences who yell at the screen before a character enters the room in which he/she will inevitably be dispatched: You’re filled with this urge to reach into the story and stop the characters from doing something that, when viewed from a distance, seems phenomenally stupid. But because we can’t do anything to stop it, our dread has no outlet. Thus we’re already filled with dread when Gilgamesh gets his first look at Humbaba, which makes for some very interesting interplay between story and audience: We not only feel exactly what the character feels, but we feel it first. This happens to be one of the most damaged portions of the poem, and our reconstruction of these events is uncertain. Mason’s translation diverges from the others here by essentially tearing through the section concerning Gilgamesh’s and Enkidu’s dreams, focusing instead on Enkidu’s wounded hand (damaged when he reaches the barrier to the Cedar Forest). This wound doesn’t appear in many of the translations – even here, Gilgamesh dismisses it – but it plays a part in Mason’s depiction of the battle. The battle is presented very differently here than in other versions. I’ve retyped Mitchell’s translation in order to compare it with Mason’s…and it’s at this point that we’ll read it!