Criminal Law – Fairfax – Fall 2009

advertisement

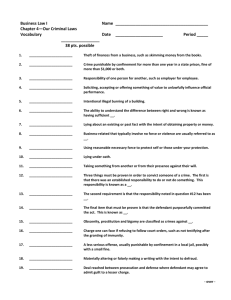

CRIMINAL LAW - FALL 2009 - FAIRFAX I. “Building Blocks” A. The basics 1) Theories of punishment -Retributivism: punishment is justified because people deserve it Grounded in notions of moral desert, backward looking -Utilitarianism: punishment is justified by the useful purposes it serves Concerned with broader benefits derived by society from imposition of punishment, forward looking Characteristics of punishment (according to Greenawalt): 1) Performed by, and directed at, agents who are responsible in some sense 2) Involves “designedly” harmful or unpleasant consequences 3) The unpleasant consequences are usually preceded by “a judgment of condemnation” 4) Imposed by one who has authority to do so 5) Imposed on an actual or supposed violator of the rule of behavior 2) Proportionality: Ewing v. California -Does the Eighth Amendment prohibit the state of California from sentencing a repeat felon to a prison term of 25 years to life (under the “three strike” rule) Court (O’Connor) says no, states can use various penological rationales Dissent (Breyer) says yes, punishment was “grossly disproportionate” 3) The Criminal Process -Complaint of a crime (detection/report/suspicion) -Investigation -Arrest -Charge -Preliminary hearing -Discovery (most discovery obligations run from the State to the defense) -Motions -Trial (bench or jury) -Sentencing/Punishment -Appeal (State cannot appeal an acquittal b/c of “double jeopardy” clause) -Collateral Review 4) Jury Nullification – when a jury acquits in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary (they have the power to do this; people argue about whether they have the right) -Double Jeopardy clause: “no person shall…be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy” 5) Construction/Interpretation of criminal statutes Principles of legality in dealing with criminal statutes: Legality: no judicial criminal lawmaking (Keeler v. Superior Court) Void-for-vagueness: legislatures cannot delegate lawmaking to the courts (In re Banks) Lenity/Strict construction: ambiguity should be resolved in favor of the defendant United States v. Foster - what does it mean to “carry a gun”? In re Banks: void-for-vagueness/overbreadth claims against “PeepingTom” statute Keeler v. Superior Court - the court assumes legislators from 1850 were codifying contemporary common law; they review “born alive” rule (w/ regard to fetus) Court’s reasoning: It is beyond the court’s authority to define crimes and fix penalties It would violate due process because of the lack of notice to defendant Dissent arguments: The majority ignored the common law The majority misconstrued the intent of the legislature B. Actus reus – the external or physical part of the crime: the “action” “Voluntary act” - volition is required for actus reus (involuntary acts are not “acts”) -Possession: Section 2.01(4) of the MPC: “possession is an act…if the possessor knowingly procured or received the thing possessed or was aware of his control thereof for a sufficient period to have been able to terminate his possession.” -Omission: Section 2.01(3) of the MPC: liability for the commission of an offense may not be based on an omission unaccompanied by action unless: (a) the omission is expressly made sufficient by the law defining the offense; or (b) a duty to perform the omitted act is otherwise imposed by law. -criminal liability for omission can only attach where there is a legal duty -when an omission may create criminal liability: 1) where a statute imposes a duty 2) a status relationship (i.e. spousal or parental) 3) contractual duty 4) voluntarily assumed duty 5) creation of a risk of harm C. Mens rea – the mental or internal part of the crime: the “intent” -under the common law, intent includes both purpose and knowledge -General intent – requires only the intent to commit the act (any moral blameworthiness) -Specific intent – requires intent to inflict the specific harm of the act (specific defined state of mind) MPC 2.02: Requirements of culpability: A person is not guilty of an offense unless he acted purposely, knowingly, recklessly, or negligently (2)(a) Purposely – conscious object to engage in conduct…or to cause such a result; awareness of the existence of attendant circumstances (2)(b) Knowingly – awareness of the existence of attendant circumstances, awareness of practical certainty that conduct will cause result (2)(c) Recklessly – conscious disregard of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element exists or will result; involves gross deviation from standard of law-abiding person (2)(d) Negligently – should be (but are not) aware of risk that the material element exists or will result; involves gross deviation from standard of reasonable person -attendant circumstances – a condition that must be present, in conjunction with the prohibited conduct or result, to constitute the crime (i.e. statutory rape: consensual sex with a female under the age of 16) -A prosecutor can establish knowledge by demonstrating willful blindness State v. Nations – State attempted to show willful blindness through the “high probability” standard of MPC 2.02(7); however, MO did not adopt the MPC statute, so the State had to show actual knowledge, instead of simply a high probability that Δ was aware that the girl was 17” -“willful” means that someone did something either (1) deliberately and intentionally or (2) in bad faith D. Strict liability offenses – offenses for which mens rea is not required -often the element that does not require mens rea is an attendant circumstance (i.e. statutory rape) - The MPC rejects strict liability for crimes Staples v. United States – Thomas says the Court requires “some indication of congressional intent…to dispense with mens rea” (it would be unjust to extend strict liability to these firearms) Justice Stevens dissent: gives 3 characteristics of “public welfare” offenses (for strict liability): 1) “Regulate dangerous/deleterious devices or products or obnoxious waste” 2) “heighten the duties of those in control of particular industries, trades, properties, or activities that affect public health, safety, or welfare” 3) “no mental element, but consist only of forbidden acts or omissions” E. Ignorance or Mistake Mistake of fact: -For General Intent crimes, only a reasonable mistake of fact provides a defense. (2 exceptions) “moral wrong doctrine” – reasonable mistake is no good in circumstances where your actions were morally wrong even if you had not been mistaken (through Δ’s eyes) “legal wrong doctrine” – reasonable mistake is no good in circumstances where your actions were illegal even if you had not been mistaken (through Δ’s eyes) -For Specific Intent crimes, a reasonable or unreasonable mistake, as long as it is genuine and negates the specific mental element of the crime -Strict liability offenses do not allow mistake of fact defenses (no mens rea element) Mistake of law: The general rule is ignorance of the law is no excuse Common law three exceptions: 1) Mistake negating mens rea “same law” mistake: mistake about law with which being charged (not a defense) “different law” mistake: mistake about law different from one with which being charged (a defense) 2) Reasonable reliance – if an individual reasonably relies upon an “official” statement of the law that is wrong 3) Fair Notice – not having reasonably “fair notice” of legal requirements may be a defense (Lambert v. California, a felon registration act in L.A.) MPC Exceptions to “ignorance is no excuse”: MPC 2.04 -ignorance or mistake is a defense if (a) the ignorance or mistake negates the purpose, knowledge, recklessness, or negligence required for a material element, or (b) the law provides that the state of mind established by such mistake constitutes a defense -the defense is not available if Δ would be guilty of another offense had situation been as he believed; in that case, the ignorance or mistake will reduce the grade and degree to the offense which he would have been guilty of had the situation been as he believed F. Causation -MPC causation: scope of liability (note 10, p222) -Actual cause (cause-in-fact): two theories 1) “But-for” causation: prohibited result would not have occurred but for the actor’s conduct 2) “Substantial factor” causation: two or more actors commit separate acts, each of which is sufficient to bring about prohibited result -Proximate cause (“legal cause”): involves intervening but-for occurrence after actor’s conduct and prior to prohibited result; analyzing proximate cause involves considerations of fairness Oxendine v. State - Jury instruction: “contribution or aggravation is not acceleration”, acceleration needed for causation Velazquez v. State -“superseding” intervening cause exculpates defendant II. Homicide A. Degrees Common Law First degree murder (premeditated & deliberate) Second degree murder (malice aforethought) Voluntary manslaughter (passion/provocation) Involuntary manslaughter (criminal negligence) Model Penal Code Murder (purposely or knowingly) Manslaughter (recklessly) Negligent Homicide (negligently) -Direct evidence – evidence of a fact -Circumstantial evidence – evidence that requires inference to reach a fact B. Intentional killings First degree murder – it requires either: (1) premeditation and deliberation; or (2) murder in the course of committing arson, burglary, robbery, or rape State v. Guthrie – premeditation and deliberation characterize a thought process without “hot blood” or passion (thus, “cold-blooded murder”) Midgett v. State – court says evidence insufficient to support conviction of first degree murder which required “premeditated and deliberate purpose of causing the death of another person” -but was sufficient to sustain second degree murder which requires “purpose of causing serious physical injury” that causes death (lesser included offense) State v. Forrest – circumstances to be considered in determining premeditation (1) want of provocation on part of deceased (2) conduct and statements of defendant before and after the killing (3) threats and declarations of the defendant before/during course of the killing (4) ill-will or previous difficulty between the parties (5) dealing of lethal blows after deceased has been felled and rendered helpless (6) evidence that the killing was done in a brutal manner Second degree murder – “the baseline murder” (can go up or down) -it requires “malice aforethought”; four ways to prove: (1) intent to kill (2) intent to cause grievous bodily injury (3) “depraved heart” – unintentional associated w/ extreme recklessness (4) intent to commit a felony Malice can be express or implied -Express malice: deliberate intention unlawfully to kill or cause grievous bodily injury -Implied malice: killing w/o provocation; killing with an “abandoned or malignant heart”; conscious disregard of risk and extreme indifference to human life Girouard v. State - the court articulates four requirements for provocation: (1) adequate provocation, (2) killing in the heat of passion, (3) heat of passion was sudden and the killing followed the provocation before there was “reasonable opportunity for the passion to cool” (4) casual connection between provocation, passion, and fatal act -common law: words alone do not constitute adequate provocation to mitigate crime Under MPC: -words are adequate provocation -victim does not have to be the one who provoked the defendant -defendant can be mistaken about what he saw that led to the killing -does not have to be sudden; it can be a “build-up” Voluntary manslaughter – intentional killing, absence of malice -Reasons for mitigating to common law voluntary manslaughter: 1) Finding one’s spouse having sex with another 2) Mutual combat 3) Assault and Battery C. Unintentional killings Involuntary manslaughter – killing as a result of negligent acts (“regular recklessness”) D. Felony-murder – killing that occurs in relation to the committing of a felony -MPC rejects the felony-murder rule -Two varieties of common law felony-murder: 1) Statutory first degree murder rule 2) Common law second degree murder rule Limitations on felony-murder rule: -The felony must be an inherently dangerous felony People v. Howard – killing occurred during high speed chase but felony as defined was not inherently dangerous (look at the abstract elements of the felony) -Independent felony “merger” rule (if felony is an integral part of the homicide) People v. Robertson – killing occurred while defendant was firing to scare robbers away, but not kill them and so merger rule did not apply (felony has no independent purpose) -In perpetration/Furtherance of a felony People v. Sophophone – killing doesn’t have to occur during the commission of a felony as long as it occurs in continuation of the action (in the “res gestae”) -time, distance, and causal relationship to the killing are all factors Killing by third party: 1) Agency approach – if killing was done by someone not involved in the felony, the perpetrator of the felony cannot be charged with felony-murder 2) Proximate causation approach – if act by the felon is the proximate cause of the killing by the non-felon, the felon can be charged with felony-murder E. Capital murder – murder punishable by death Furman v. Georgia - Court holds that states must separate conviction and sentencing phase to sustain capital punishment sentences (bifurcated trial) -challenges to death penalty come under Eighth Amendment Gregg v. Georgia – arguments for/against capital punishment (p342-349) III. Rape -Consent is a complete defense -Limitations: (1) consent may be withdrawn at any time prior to penetration (2) consent cannot be induced by fear or violence (3) prior consent is not consent for the instant act (4) forcible persistence following post-penetration withdrawal of consent renders an offense less than rape (some degree of sexual assault) -Rape is a general intent crime (only requirement is moral blameworthiness) A. Common law elements of Rape Actus reus elements of rape: 1) Intercourse (penetration) 2) Force (actual or constructive, includes threats) 3) Non-Consent and/or Against the Will (“forcible compulsion”) -threatened force must be physical (cannot threaten non-physical, i.e. humiliation or criminal action) State v. Alston – State did not have to show actual force; constructive force (threats of harm) is sufficient Commonwealth v. Berkowitz – PA Supreme Court found no forcible compulsion and found simple “no’s” as insufficient for claim of nonconsent People v. John Z. - CA Supreme Court finds that a withdrawal of consent “effectively nullifies any earlier consent and subjects the male to forcible rape charges” if he forcibly continues despite the objection B. Rape by fraud -Fraud in factum (vitiates/nullifies consent) vs. Fraud in inducement (does not vitiate) C. Rape reform efforts: -push to abolish force/resistance requirement (shift focus from force to consent) -gender neutrality (most statutory rape statutes are not gender neutral) -rape shield laws (most jurisdictions have them but very few are strong) -marital immunity IV. Defenses A. Types 1) Failure of proof – negation of an element or elements of a crime 2) Offense modification – exculpation of an actor despite proof of elements (i.e. paying a ransom) 3) Public policy defenses – actors are culpable, but forward-looking public policy arguments end pursuit of conviction (i.e. statute of limitations, diplom. immunity) 4) Justification – the harm of the act is justified by the need to avoid an even greater harm or further a greater societal interest (i.e. self-defense) 5) Excuse – no justification for the act, but conditions suggest a lack of moral blameworthiness B. Self-Defense Requirements for invoking self-defense in homicide: 1) Threat, actual or apparent, of use of deadly force 2) Threat must have been unlawful and immediate 3) Defendant must have believed he was in imminent peril of death or serious harm 4) Defendant must have believed that his use of force was necessary to save himself (and the necessity cannot be self-created; the slayer must not have provoked) 5) The beliefs of defendant must be objectively reasonable in light of circumstances (reasonable and proportional) -If an individual provokes, but later communicates his withdrawal and withdraws, he again can claim selfdefense if the other party continues the confrontation United States v. Peterson - court finds that self-defense “is a law of necessity” and that “one who is the aggressor in a conflict culminating in death cannot invoke the necessities of self-preservation” -D.C. Court adopts common law “retreat to the wall” requirement -however, majority of American jurisdictions allow an individual to stand his ground and use deadly force “whenever it seems reasonably necessary” (subjective test) -Common law says that deadly force may not be used to repel a non-deadly attack MPC says deadly force may only be used to prevent death, serious injury, kidnapping, or rape People v. Goetz – determination of “reasonableness” must be based on circumstances facing a Δ, including relevant knowledge the Δ had about the potential assailant, physical attributes of all persons involved, and prior experiences the Δ had providing a basis for belief of bad intent -“Partial” or “Imperfect” self-defense: defendant proves only some elements of his self-defense, and so is not acquitted but charges are mitigated (not everywhere; some jurisdictions are all or nothing) -Imperfect self-defense occurs when (1) defendant’s genuine belief of a threat is unreasonable, or (2) defendant uses lethal force to repel non-lethal force, or (3) defendant provoked the confrontation State v. Norman - Defense offered testimony of a doctor who testified that Norman suffered from Battered Woman Syndrome and so the threat of severe harm or death was essentially always imminent (response to state’s claim of absence of imminent threat) -NC Supreme Court reverses intermediate decision and finds no basis for perfect self-defense claim; Norman is convicted of voluntary manslaughter (her sentence was later commuted) Other common law self-defense principles: -One may use deadly force in defense of another (even if you are reasonably mistaken) -One may not use deadly force in defense of property (but you can threaten) -Some jurisdictions permit use of deadly force in defense of home (to prevent intrusion) Others only permit such use of force when there is a reasonable threat Others further limit such use of force to defending against certain felonies -One may not use deadly force to prevent a crime (exception: serious felonies) MPC Self-Defense (3.04) (1) Use of force justifiable for protection of person (2) Limitations: resisting arrest, resisting force while on another’s property, deadly force is only justifiable to protect against serious harm (death, serious bodily harm, kidnapping, rape) (3) A person may estimate the necessity of force, subject to the limitations of the statute C. Necessity -A justification defense: “choice of evils” Common law elements to necessity defense: 1) Act charged must have been done to prevent a significant evil 2) There must have been no adequate alternative 3) The harm caused must have not been disproportionate to the harm avoided 4) The cause bringing about the necessity must have been nonhuman 5) Imminence requirement MPC elements to necessity defense: 1) Conduct that actor believes necessary to avoid a harm or evil, provided that a) Harm or evil sought to be avoided is greater than that of the conduct b) Neither the Code nor other law defining the offense provides exceptions or defenses for the specific situation involved c) There is no legislative purpose to exclude the justification claimed 2) Actor cannot have been reckless or negligent in bringing about situation requiring the choice Nelson v. State - Clearly the taking of and damage to the two highway dept. vehicles was not necessary to avoid some greater harm (in this case, the defendant’s stuck truck) -the MPC rejects any limitations on necessity cast in terms of particular evils to be avoided or particular evils to be justified (nothing is off-limits) D. Duress -Is duress a justification or an excuse? (depends on the severity of the harm avoided/produced) -Typical common law guidelines (combine w/ elements from Contento-Pachon): 1) Another person threatened to kill or grievously injure actor or another person 2) Actor cannot be at fault in exposing himself to the threat 3) Duress is not a defense to murder or other intentional killings 4) Duress is only a defense if the coercive agent is human 5) There must not have been reasonable opportunity to escape the threatened harm United States v. Contento-Pachon – cocaine smuggling case where smuggler was caught in LAX, claimed that he believed that his family would be killed if he did not smuggle the drugs -Common law elements of duress according to Contento-Pachon: 1) An immediate threat of death or serious bodily injury (to actor or to others) 2) A well-grounded fear that the threat will be carried out 3) No reasonable opportunity to escape the threatened harm -MPC Duress (2.09): measured against a “person of reasonable firmness” E. Insanity Procedural Overview: Competency hearing, then Pretrial notice of intent to claim defense -Two insanity verdict options: 1) Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity (NGRI) or 2) Guilty But Mentally Ill (GBMI) -Why do we excuse for insanity? (lack of moral blameworthiness?) Utilitarian: good b/c incapacitates the person Retributivist: bad b/c punishment with lack of appreciation Different tests for the insanity defense: M’Naughten Rule – Requires that at the time of the act the defendant was suffering from a “defect of reason” or “disease of the mind” such that he either a) did not know the nature and quality of the act he was doing b) did not know that what he was doing was wrong Irresistible Impulse/Control test – individual had no control over actions when crime occurred “Product” test – defense available if act was the product of Δ’s mental defect or disease (enunciated in Durham; very dependent on expert testimony) MPC test – requires that at the time of the conduct: a) Δ lacked substantial capacity to appreciate criminality/wrongness of his conduct, or b) Δ lacked substantial capacity to conform his conduct to the requirements of law -following Hinckley acquittal, there was public backlash and reaction in the legislatures; many jurisdictions went back to M’Naughten rule or abandoned defense altogether F. Diminished Capacity (MPC 4.02 – a failure of proof defense) - deals with mental abnormalities that do not reach the threshold of legal insanity Two variants: 1) mens rea variant – mental abnormality negates mens rea element (failure of proof) -Successful defense = acquittal, but elements of lesser crime may have been met -Majority approach in the U.S. 2) partial responsibility variant – mental abnormality makes defendant not fully responsible -Successful defense results in conviction of lesser crime or lesser sentence -Minority approach (few states recognize; those that do only apply it to homicide) People v. Wetmore – Δ had a history of psychotic illness and lived in another’s apartment for several days; defense could claim mens rea variant based on lack of requisite intent for burglary Intoxication -Voluntary and involuntary (involuntary is very rare) – can never negate recklessness/negligence -Only relevant as to the capacity of the actor to commit the requisite intent of the crime -Voluntary intoxication not a defense to a crime, however common law allows for the negation of a specific intent due to intoxication (and in some instances will allow negation of actus reus) -The defense has also been used to show that a Δ was physically incapable of committing the crime -The MPC requires that intoxication “negative an element of the offense” -Four types of involuntary intoxication: (1) Coerced, (2) Pathological, (3) Mistake, (4) Unexpected from a Rx drug Commonwealth v. Graves – defendant drank a quart of wine and took LSD, then burglarized a house and robbed a man inside; the elderly victim later died of his injuries -Δ alleged that the court erroneously denied his suggestion for jury instructions that allows for consideration of intoxication to negate specific intent, and to a question of an expert witness whether or not Graves could have consciously formed the specific intent necessary for the crime -court found that intoxication was not an excuse or exoneration, but ruled that intoxication could be introduced to negate an element of the crime (in this case, specific intent of robbery/burglary) Addiction/Alcoholism Robinson v. California – CA statute makes it a criminal offense to “be addicted to the use of narcotics”; defendant charged and convicted under the statute relating to use of heroin -Court finds that a law that imprisons a person afflicted with the status addiction inflicts cruel and unusual punishment and is unconstitutional under 8th and 14th Amendments Powell v. Texas - issue of whether defendant, charged and convicted of public intoxication, could assert the alcoholism as a defense (as a “chronic disease”) -The court evaluates alcoholism as a disease, the various ways of dealing with the problem through the criminal system, and generally finds that alcoholics do not suffer from an irresistible compulsion to drink that excuses them from culpability -Distinguishes this case from Robinson because the statute in question was punishing criminal behavior in public, not private behavior Infancy (4.10) In re: Devon T – 13-year old convicted in juvenile court with possession of heroin with intent to distribute -Three philosophical bases for the infancy defense: 1) Lack of moral culpability 2) Different (lower) capacity 3) Threat of punishment not a deterrent -The court analogizes that a juvenile could argue the defense of insanity, mental retardation, or involuntary intoxication; shouldn’t they be able to argue infancy? General common law rules on infancy: -Younger than 7 years, barred from conviction -Older than 14 years, cannot claim infancy defense - Between 7 and 14, rebuttable presumption that he doesn’t have capacity to commit the crime Cultural defenses “Rotten social background” defense: case with Marines and black patrons at the diner -Mere words alone are not sufficient provocation (couldn’t mitigate murder) -D.C. Circuit rejected the defense, but dissenting Judge Bazelon formulated a general proposition for the defense (Condemnable Act, Condemnable Actor, Society allowed to sit in condemnation) Culture practice defense: State v. Kargar (man kissing his son’s penis case) -de minimis statutes excuse criminal behavior for reasons of culture or tradition -often discriminatory against women/children V. Inchoate Offenses -all inchoate offenses deal with conduct that is designed to culminate in the commission of a substantive offense, but has failed to do so or has not achieved its culmination -The major inchoate offenses: attempt, solicitation, and conspiracy A. Attempt -either in provisions in specific statute or in general attempt provisions -Dual intent: both intent to perform the actus reus, and intent to commit the underlying offense -Incomplete attempt: actor does some of the acts intended, but then is prevented from continuing them -Complete attempt: actor does every act intended, but fails to produce intended result -Common law: attempt to commit a felony is a felony, attempt to commit a misdemeanor is a misdemeanor (but the degree of the offense and sentence is less severe) -MPC: attempt to commit a crime is treated and punished the same as the underlying offense (with the exception of a first degree felony, which is mitigated to second degree) People v. Gentry – defendant charged and convicted with attempted murder in Illinois after he spilled gasoline on his girlfriend and the gasoline ignited, severely burning her -Ill. Supreme Court has held that “a finding of specific intent to kill is a necessary element of the crime of attempted murder.” -Only the specific intent to kill qualifies for attempted murder (this is CL rule) Common law intent includes both purpose and knowledge Bruce v. State – defendant charged and convicted of attempted felony murder; he appealed on the basis that attempted felony murder was not a crime in MD -MD’s felony murder statute requires the State to prove a specific intent to commit the underlying felony and that death occurred in the perpetration or attempt to perpetrate it -MD’s attempt statute is a general attempt law (applies to any crime): “a specific intent to commit the offense coupled with some overt act in furtherance of the intent that goes beyond mere preparation.” -Court agrees with common law rule that there is no attempted felony murder (exception: FL) Attempt murder under MPC -there cannot be attempted murder under 5.01(1)(b) because there is no belief that the action will have the result of death -there can be attempt murder if it is committed purposely (“with the purpose of causing”) -there may be attempt murder if it is committed knowingly (distinction between “know” and “believe”). States that have adopted 5.01 have tried to refine knowledge vs. belief -there cannot be attempt murder if it is committed recklessly (no purpose or belief) -there cannot be attempt manslaughter if it is committed recklessly (no purpose or belief) -there can be attempt manslaughter if it is committed purposely and mitigated Simmons v. State – the court carries the policy of strict liability from the underlying crime of statutory rape to the attempt U.S. v. Mandujano – hybrid general/specific attempt statute (specific to that particular title, but general to the crimes within) -distinction between mere preparation and attempt (because up to a certain level, the perpetrator can still decide not to commit the crime) Common law tests for preparation/perpetration distinction 1) Physical proximity test 2) Dangerous proximity test – how close you are to the danger and the severity of harm and degree of apprehension People v. Rizzo (no attempt when robbers drove around trying to find the target) 3) Indispensable element test – elements that are critical to perpetration of the crime 4) Probable desistence test – reached a point where voluntary desistence is unlikely 5) Abnormal step test – steps toward the crime beyond conduct of a normal citizen 6) Res ipsa loquitor (or “unequivocality”) test – conduct itself manifests criminal purpose MPC: act must be a substantial step in a course of conduct designed to achieve criminal result Defenses for Attempt: -Under the common law, factual impossibility is not a defense -Under the common law, legal impossibility is a defense -in the factual impossibility situation, the mistake of fact prevents the actor from completing the offense, but the mens rea (intent to injure) and actus reus (i.e. stab) of the attempt are present -Legal impossibility broken down: “pure” legal impossibility and “hybrid” legal impossibility Pure: Legal mistake (defense) Hybrid: Factual mistake, but relates to an attendant circumstance (not a defense) -another defense: Abandonment (not a defense at majority common law) MPC 5.01(4) gives an attempt defense for abandonment/withdrawal/renunciation -MPC Withdrawal for Attempt: complete and voluntary renunciation of criminal purpose; not voluntary if motivated by desire to avoid detection or postpone the criminal conduct People v. Thousand – chatroom predator case (hybrid legal impossibility – not a defense) B. Solicitation -Common law: “asking, enticing, inducing, or counseling of another to commit a crime” The solicitor conceives the criminal idea and furthers its commission via another person -mens rea: specific intent crime (you have to be sure there is intent that the act be commited) -actus reus: complete upon the asking/enticing/inducing (no additional step required) -for uncommunicated solicitation, common law says no and MPC says yes However, some jurisdictions recognize the crime of attempted solicitation -at common law but not MPC, solicitation carries a lighter punishment than attempt -at common law and MPC, solicitation merges into the underlying offense if it is completed -For CL, cannot be guilty of solicitation if plan is already in place (opposite is true for MPC) -renunciation of criminal purpose is an affirmative defense (similar to attempt) But this only activates if the criminal offense is prevented from happening and a genuine renunciation of criminal purpose C. Conspiracy -At common law, requires mutual agreement or understanding 1) Express or Implied, 2) Between two or more persons, 3) To commit a criminal act or to accomplish a legal act by unlawful means -Twofold specific intent required (for exam, knowledge alone satisfies intent): (1) Intent to combine with others AND (2) Intent to accomplish the illegal objective -The key to conspiracy is whether there was an agreement -some jurisdictions require an overt act, in most agreement is enough -common law: can be punished for both conspiracy and the substantive crime, no merger (common law) -For MPC: Conspiracy merges into the target crime, no double conviction Unless a first or second-degree felony, prosecution must prove an overt act - MPC rejects Pinkerton; for conspiracy conviction, Δ had to solicit commission of the offense or aid in its commission -In jurisdictions that require an overt act to activate criminal conspiracy, any overt act by any one of the conspirators satisfies the requirement -Group crimes: higher chance the crime will occur; lower chance the attempt will be abandoned But also a higher chance of apprehension prior to the attempt Pinkerton v. United States -“Pinkerton Rule”: each co-conspirator is responsible for any “reasonably foreseeable” crime by a co-conspirator in furtherance of the conspiracy (exposure to enhanced criminal liability) People v. Lauria – defendant charged and convicted of conspiracy related to his operation of a phone answering service that was used by prostitutes (issue of knowledge and intent) -criminal conspiracy requires (1) knowledge of the use of services for illegal purposes (2) intent to further that use -intent to further the conspiracy can be inferred from knowledge when: 1) the purveyor of legal goods for illegal use has acquired a stake in the venture 2) no legitimate use for the goods or services exists 3) the volume of business with the buyer is grossly disproportionate to any legitimate demand, or sales for illegal use are high proportion of seller’s business -after the initial forming of the conspiracy, a conspirator that changes his mind can only get off the hook if he “thwarted the success of the conspiracy, under circumstances manifesting a complete and voluntary renunciation of his criminal purpose.” (MPC) -Commonwealth v. Cook – you cannot prove conspiracy through conjecture (only facts) -Commonwealth v. Azim – circumstances relevant to proving conspiracy are: (1) association with alleged conspirators, (2) knowledge of the commission of the crime, (3) presence at the scene of the crime, and at times, (4) participation in the object of the conspiracy -The “corrupt motive” doctrine: minority doctrine (also rejected by MPC) where parties are not held to be guilty of involvement in conspiracy unless they had a “corrupt motive” Unilateral conspiracy requires that only one of the alleged conspirators needs to agree to create conspiracy (MPC uses unilateral approach, but common law majority is bilateral approach) People v. Foster – absence of agreement because one party did not want to commit crime Types of conspiracies: -“Wheel” conspiracy: hub and spokes (harder to prove b/c spokes don’t know each other) -“Chain” conspiracy: links in the chain (easier to prove b/c each member’s role is necessary) -Every conspirator does not have to agree with all the other conspirators to form a conspiracy Bilateral conspiracy requires the agreement of only two (Kilgore v. State) -Generally, one agreement = one conspiracy (2+ objectives does not mean 2+ conspiracies) Wharton’s Rule –when the crime requires the participation of two or more persons, the conspiracy merges into the substantive offense (i.e. adultery, dueling, incest) However, does not apply when crime involves more people than necessary for offense Iannelli v. U.S. – federal gambling statute making it a crime for five or more persons to conduct, finance, manage, supervise, direct, or own a gambling business prohibited by state law -Withdrawal under common law: affirmative and bonified rejection of the conspiracy that is communicated to the co-conspirators -In jurisdictions requiring an overt act, complete defense if occurs before the overt act, defense to the substantive offense but not the conspiracy if occurs after the overt act -In jurisdictions not requiring an overt act, only a defense to subsequent acts by the conspiracy -Withdrawal under MPC: renunciation is an affirmative defense to the crime of conspiracy, but it requires the successful thwarting of the substantive crime intended by the conspiracy OVERVIEW OF CONSPIRACY COMMON LAW No overt act required (majority rule) Bilateral (but modern trend toward unilateral) Does not merge with substantive offense Punished at lower level than offense MODEL PENAL CODE Overt act req’d unless 1st or 2nd deg. offense Unilateral Generally merges with substantive offense Punished at same level as offense D. Accomplice Liability -As a result of complicity in a crime, a person may be liable/guilty for criminal acts of another -Sometimes called “derivative liability” -Conspiracy requires proof of agreement; Accomplice liability requires proof of assistance Four common categories of complicity: 1) Principal in the first degree (perpetrates the crime) 2) Principal in the second degree (aids, counsels, encourages the perpetrator and is present) 3) Accessory in the first degree (aids, counsels, encourages, the perpetrator but not present) 4) Accessory in the second degree (renders assistance to the perpetrator after the crime) An accessory in the second degree must have knowledge of the other’s guilt -The first three categories are considered serious and usually punished at the same level as the substantive crime (the fourth is less serious) -Actus reus of accomplice liability is assistance to the primary perpetrating party -Common law mens rea is dual intent: (1) Intent to assist, and (2) Intent that the crime be committed (the majority rule is that intent means “purpose”) MPC mens rea: purpose of promoting or facilitating the commission of the crime -MPC 2.06(3)(a): A person is an accomplice of another person in the commission of a crime if 1) He solicits another person to commit the offense, or 2) He aids or agrees or attempts to aid such other person in planning or committing it, or 3) He fails to make an effort to prevent the commission of the offense (if he has legal duty) -Target offenses not requiring intent 1) Alleged accomplice had intent to assist 2) Alleged accomplice had requisite mental state for target offense - MPC 2.06(4) takes pretty much the same approach as common law in this regard -Natural-and-probable consequences (State v. Linscott – robbery/murder at the coke dealer’s house) Common law: accomplice is liable for a crime in which he assisted as well as all other crimes that were natural and probable consequence of the crime in which he assisted (similar to Pinkerton) -MPC rejects natural-and -probable consequences rule -Attendant circumstances (State v. Hoselton – lookout during the barge robbery) Common law: requires that alleged accomplice have mental state of the underlying offense MPC: doesn’t take a position and leaves the question open -in many jurisdictions, states abrogate principals in the first and principals in the second degree and allow prosecutors to charge principals in the second degree (like lookouts) as principals in the first -If someone has a duty to prevent a crime, generally jurisdictions will apply accomplice liability for an omission (but actus reus omission and mens rea required) -Presence can be enough if you are genuinely acting as a lookout, even if you did not have to discharge your duty as a lookout (telling them the police were coming) -But if you’re just there? (State v. Vaillancourt) Common law doctrine: mere presence is not enough, but courts have been willing to recognize accomplice liability when the person’s presence bolstered or encouraged the perpetrator Wilcox v. Jeffery – Wilcox charged with aiding and abetting the violation of immigration employment law for covering the concert of Coleman Hawkins (saxophonist) and applauding -Stretching it, but actus reus is presence at the concert without objecting and mens rea is intent that the saxophonist play and intent to assist him play (encouragement through applause) -Majority approach: but-for causation not necessary to prove assistance accomplice liability (the result could have been inevitable long before assistance was rendered) MPC follows this approach as well -Common law: there still must have been some assistance, no matter how minimal – intent and attempt to assist is not enough -MPC: intent to assist is sufficient (still on the hook for accomplice liability even if try to assist fails) -Common law: you can derive liability from aiding in attempts -MPC 5.01: allows conviction of an accomplice even when the primary actor’s target offense fails -Common law requires derivative liability (if principal is acquitted, accomplice cannot be guilty) -MPC does not require derivative liability Bailey v. Commonwealth -No derivative liability, because police officer was justified in killing Murdoch -But, Bailey is a principal in the first degree, because he was the primary cause of the murder In re Meagan R. – statutory rape involves two parties (male and underage female), but female action is not punished because it was legislature’s intent to protect her (she is not liable for aiding and abetting) -The difference between conspiracy liability and accomplice liability: with accomplice liability, the defendant is liable for the natural and probable consequences of the offense she intentionally assisted, whereas with conspiracy liability, the defendant is liable for the natural and probable consequences of the conspiracy she joined (Pinkerton rule; much broader) -whenever there is accomplice liability, be on the lookout for conspiracy/solicitation (and vice-versa!)