October 29, 2015 Law Club Handout

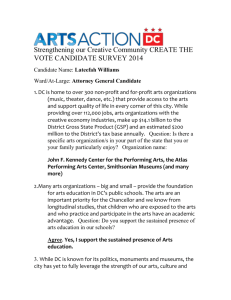

advertisement