Tart Lizzie Tart Jeffrey Peake Honors English III 1 December 2011

advertisement

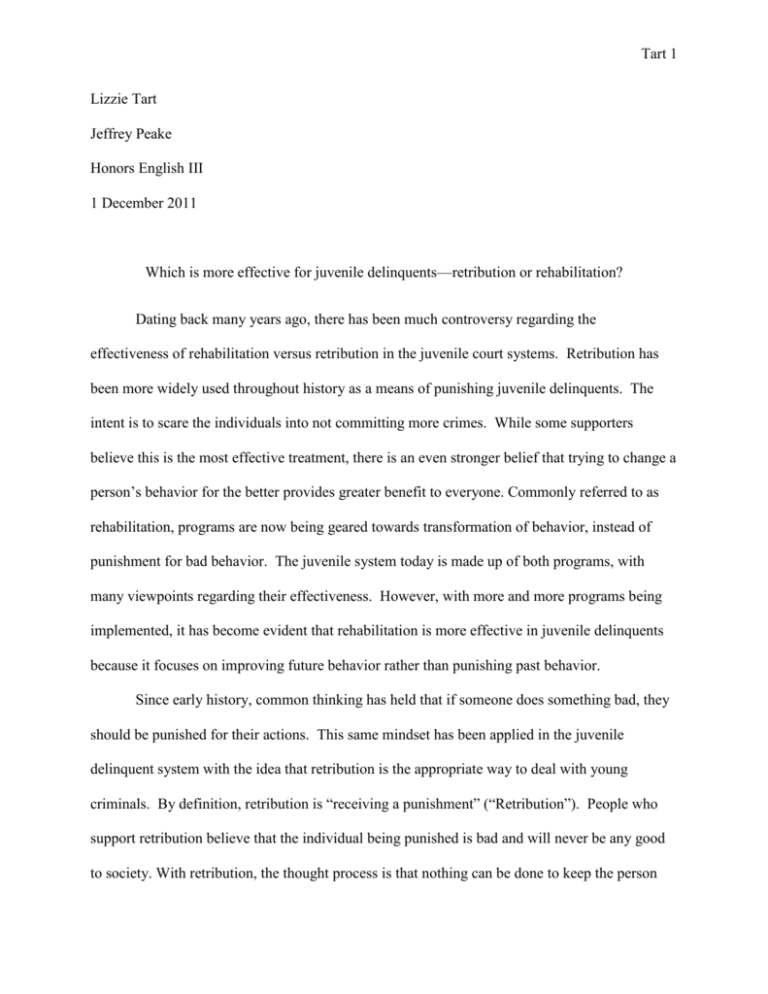

Tart 1 Lizzie Tart Jeffrey Peake Honors English III 1 December 2011 Which is more effective for juvenile delinquents—retribution or rehabilitation? Dating back many years ago, there has been much controversy regarding the effectiveness of rehabilitation versus retribution in the juvenile court systems. Retribution has been more widely used throughout history as a means of punishing juvenile delinquents. The intent is to scare the individuals into not committing more crimes. While some supporters believe this is the most effective treatment, there is an even stronger belief that trying to change a person’s behavior for the better provides greater benefit to everyone. Commonly referred to as rehabilitation, programs are now being geared towards transformation of behavior, instead of punishment for bad behavior. The juvenile system today is made up of both programs, with many viewpoints regarding their effectiveness. However, with more and more programs being implemented, it has become evident that rehabilitation is more effective in juvenile delinquents because it focuses on improving future behavior rather than punishing past behavior. Since early history, common thinking has held that if someone does something bad, they should be punished for their actions. This same mindset has been applied in the juvenile delinquent system with the idea that retribution is the appropriate way to deal with young criminals. By definition, retribution is “receiving a punishment” (“Retribution”). People who support retribution believe that the individual being punished is bad and will never be any good to society. With retribution, the thought process is that nothing can be done to keep the person Tart 2 from committing other, more serious crimes. In the 1960’s when the crime rate sharply increased, this method of discipline became more extensively used. People started believing that therapeutic solutions did not work, and the only option was to create more programs based on disciplinary solutions. According to John Dilulio, a political scientist, many juvenile delinquents were “super predators” and were “radically impulsive, brutally remorseless youngsters, including ever more teenage boys who murder, assault, rob, burglarize, deal deadly drugs, join gun-toting gangs, and create serious disorders” (Piquero). From observations such as this, it was obvious that nothing good could come from these individuals and punishment was the only alternative. Although jail time is the most common form of punishment, retribution can be more than just sentencing a youth to prison. Youth detention centers, probation, and protective supervision are all methods of “justice” used to address juvenile delinquency in today’s society. In some cases, when it seemed nothing else would work, retribution has proven to be the only form of effective punishment. However, in today’s society, it most likely would not be the chosen method except when dealing with serious felons or repeat offenders (Rawls). Statistics show that about 30% of young offenders become repeat offenders, but this rate increases once they are imprisoned (Lamb). The most effective impact of correcting bad behavior in juveniles needs to occur before they end up in jail. The only real way to take someone corrupt and try to make them virtuous is to do it before they end up in jail. Rehabilitation is the opposite of retribution. In this approach, the system finds sources of treatment that target common factors of delinquency and treat the needs of adolescents in hopes of transformation. The goal is to reform them into involved members of society. This is a longterm treatment—a customized approach to prevent juveniles from becoming repeat offenders. The intent is to provide a hopeful future for the children in the rehabilitation process. In today’s Tart 3 society, rehabilitation is more likely to be used and in turn, there are more options available for rehab treatment. Some examples include youth development centers, cognitive behavior programs, and social treatment programs, along with more localized programs like Structured Day, New Directions, Healthy Choice, and Teen Courts (Rawls). These methods are more logical approaches in treating juvenile delinquents. Adolescents are the future of society, and instead of wasting their lives in prison, they need to make something of themselves—the future depends on it. Michael Rieder, the former executive director of Haven House, says that his “program serves about 1,400 young people each year, many of whom the juvenile court system refers. Of those who complete the program, 90% do not commit another crime” (Lamb). In programs such as Haven House, juveniles get access to therapy, diversion opportunities, and structured day programs. The main goal of rehabilitative solutions is to save the at-risk individuals by offering hope for a better future. Each type of rehabilitation in the juvenile justice system is very detailed. It is created to fit the needs of an individual, not just the whole. For a young child who comes from an abusive background, social treatment programs sometimes are the best option. Students who may have been suspended from school or have gotten in trouble for truancy might benefit the most from Structured Day programs (Rawls). Teen Courts are designed for minor crimes and first offenders because they try to provide a change in attitude and demeanor. Michael Cox, who went through a youth development center commented, “Those programs save lives. If it wasn’t for those youth development centers, I could have been killed; I could have gotten involved in more serious crimes” (Mildwurf). All programs are used to help adolescents recover in a unique way. Tart 4 A very common approach to rehabilitation in North Carolina is Teen Courts. Also called youth or peer courts, teen courts offer a different approach where teens that are first time offenders can experience real-life court and take responsibility for their actions, in both education and service opportunities (“North”). Out of all juvenile prevention programs in the country, they are considered one of the “fastest growing”. It gives adolescents a chance to learn from their mistakes, and it teaches them about the judicial processes (Herman). Teen court programs are made up of a mock court situation in which other teenagers serve as lawyers, jurors and court reporters. Each session is facilitated by a sworn judge and a licensed attorney. Statistics show that there were only 78 teen courts in operation in 1994. In 2002, it was shown that over 900 programs were in service in the United States (Herman). As all other types of rehabilitative treatments are specialized, teen courts are no different. Usually, the only people getting sent there are teens from ages ten to fifteen, and are mostly first-time offenders or teens who have committed minor misdemeanors. Evidence has shown that the majority of young people who have made a teen court appearance stay out of trouble in the future (“North”). Jeffrey Butts found that “in three of four youth courts studies, the six-month recidivism rate for youth court was lower than that of the comparison group” (Herman). Teen Courts also provide community involvement—the “good kids” get to experience it, too. It is a hands-on experience for students in the justice system; they are the ones organizing the whole court process. Although it is only one method for providing solutions to at-risk youth, it is widely embraced by local communities and praised for its success in reducing repeat offender occurrences. Whether one is an advocate of rehabilitation or a critic, there is a general consensus that some juveniles simply cannot be rehabilitated (Lamb). A poll taken on WRAL’s website in March 2009 indicates an overwhelming majority of poll participants believe there are indeed Tart 5 juvenile offenders who can never be rehabilitated (see the diagram below). In those situations, retribution may be the only answer. But for those members of society, who are involved closely in the correctional process, they know the impact of these programs and they have seen the success stories firsthand. Judge Addie Rawls, District Court Judge for Harnett, Johnston and Lee counties, works with juvenile delinquents on a daily basis. As a juvenile court counselor, she has experience with both retributive and rehabilitative treatments in youth. She says that today, the juvenile justice system focuses more on treatment of adolescents and prevention of future crime and less on punishing those who have committed crimes (Rawls). She is currently facilitating a teen court program in Johnston County, with community and citizen involvement. Are there some juvenile offenders who cannot be rehabilitated? 14% I don't know. No, every juvenile delinquent can be rehabilitated 6% in some way. 79% Yes, some juveniles will never be rehabilitated. 0 Generated by Lizzie Tart 1000 2000 3000 4000 Number of Votes 5000 6000 The ultimate way to know whether rehabilitation or retribution works better is to look at the recidivism in both. Recidivism is when someone repeats a crime after completing punishment Tart 6 for the first crime. Recidivism rates overall are lower for rehabilitation than retribution. The number of juveniles who commit another crime after getting treatment has decreased from 53% to 33% (Lamb). This proves that alternative sources of treatment rather than punishment are the best when it comes to the juvenile justice system. A constant hurdle in keeping recidivism rates low is the ability to maintain effective treatment services for juvenile delinquents. With continuous budget cuts, many state-funded programs are being eliminated. After passing the 1998 Juvenile Justice Reform Act, North Carolina became the second state to mandate state funding only for those rehabilitative services with proven effectiveness (Lipsey). This of course involved the need for an evaluation system to track the effectiveness of these treatment programs, another cost added to the process. Keeping juveniles out of the adult court system also poses another challenge. In 2006, North Carolina experienced one of its highest juvenile crime rates reported at 36.21%. Although there has been a decline in recent years, the general fluctuation in juvenile crime has at times backlogged juvenile courts with more than just petty crimes, including cases of murder, rape and robbery (Lamb). While there will always be obstacles, rehabilitation has certainly proven itself in modern society. Programs that focus on group counseling, mentoring and family involvement have a significant impact on reduction in recidivism (Lipsey). Research into the effectiveness of teen court programs has also shown promising results (Herman). Keeping first-time offenders of nonviolent out of the juvenile justice system raises accountability for the crimes committed and reduces recidivism (Herman). Instead of punishing past behavior, it focuses on improving future behavior. Therefore, it is more effective overall. Tart 7 Works Cited Herman, Madelynn M. “Juvenile Justice Trends in 2002 Teen Courts—A Juvenile Justice Diversion Program”. National Center for State Courts. National Center for State Courts, 22 November 2002. Web. 10 October 2011. Lamb, Amanda. “NC’s juvenile justice system faces challenges”. WRAL.com. Capitol Broadcasting Company, 11 March 2009. Web. 2 October 2011. Lipsey, Mark W. “Improving the Effectiveness of Juvenile Justice Programs”. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform. Georgetown Public Policy Institute, 26 October 2011. Web. 28 October 2011. Mildwurf, Bruce. “Cuts to NC juvenile justice budget pose ‘public safety issues’”. WRAL.com. Capitol Broadcasting Company, 23 May 2011. Web. 2 October 2011. “North Carolina Teen Court Association Publications”. NCTeenCourts.org. NC Teen Court Association, 2011. Web. 21 October 2011. Piquero, Alex R. “Never too late: Public optimism about juvenile rehabilitation”. Punishment & Society. SAGE Publications, 11 October 2011. Web. 28 October 2011. Rawls, Addie. Personal Interview. 19 September 2011. “Retribution”. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC, 2011. Web. 10 October 2011.