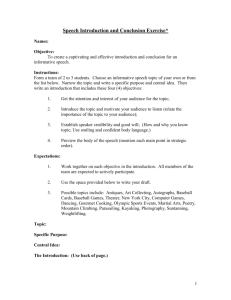

Baseball Vice: Gambling - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

Baseball Vice: Gambling and Scandal "Any professional base ball club will 'throw' a game if there is money in it. A horse race is a pretty safe thing to speculate on in comparison with the average ball match." -- Beadle's Dime Base Ball Player, 1875 Artemus Ward Dep. of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu Introduction • Why have baseball and gambling been linked from the sport’s beginnings? • Why are baseball officials so sensitive to gambling issues? • Is there a relationship between money in terms of player salaries and team revenues (or lack thereof) and gambling? • Should baseball punish individuals for being involved with gambling? If so what should be the penalty? New York Mutuals (1865) • As with all contests, gambling has been associated with baseball from the beginning. • At the end of the Civil War, a betting scandal nearly destroyed the Mutuals, a professional team organized by corrupt Tammany Hall boss William Marcy Tweed. • The catcher, third baseman and shortstop, who claimed they were victimized by a "wicked conspiracy", were all banned from baseball for accepting $100 apiece to throw a game. Ken Burns’ Baseball Clip: Gambling Synonymous With Baseball 2:09 The National League and the 1877 Conspiracy • • • • • Ken Burns’ Baseball Clip: National League Survives First Gambling Scandal 4:24 • One reason the National League was founded was because there was a lucrative market for exhibiting baseball games that were free from vices such as gambling. In 1877, after a great run early in the season, the Louisville Grays mysteriously lost seven games in a row. Four players were found to have thrown games in exchange for bribes from gamblers, or had knowledge of such transactions and would not cooperate. The players (Jim Devlin [left], George Hall, Al Nichols and Bill Craver) were suspended by their clubs, later supported by National League President William Hulbert. The players claimed they threw the games because their owner had failed to meet payroll obligations and begged for forgiveness, but Hulbert would hear none of it and the players were never reinstated. Louisville dropped out of the circuit and St. Louis followed, partly in consequence. 1905 World Series • John McGraw, manager of the National League's New York Giants, won $400 betting on his team to win the 1905 World Series. • McGraw had held his team out of the 1904 Series against Boston because of a grudge against American League president Ban Johnson, who had suspended and publicly ripped McGraw for his boorish on-field behavior during McGraw's tenure as an American League manager. • But McGraw agreed to take on Connie Mack's Philadelphia A's following the 1905 season. • Led by Christy Mathewson's three shutouts (thrown in a span of six days), the Giants beat the A's in five games and McGraw got his money and his revenge on Johnson. The winnings were known to the public, and would have almost certainly gotten McGraw banned from baseball in a later day. 1908 Bribery Attempt • On the eve of the one-game playoff between the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants that resulted from the Merkle boner and would decide the National League championship, an umpire refused an attempted bribe intended to help the Giants win. • The Giants lost to the Cubs, and the matter was kept fairly quiet. But the story came out the following spring, an official inquiry was launched by the National League but the results were kept secret. • The Giants' team physician for 1908 was reportedly the culprit and was banned for life. • Recent research has suggested that the team physician was allowed to be the "scapegoat"; some baseball historians now suspect that the Giants' manager, John McGraw, was behind the physician's bribe attempt, or that it may in fact have been McGraw himself who approached the umpire. If true, and had it become known, it could have been disastrous, as McGraw was such a prominent figure in the game. The O’Connor-Howell Conspiracy (1910) • • • • On the last day of the regular season in 1910, the St. Louis Browns were scheduled to play a doubleheader against Cleveland at Sportsman’s Park. Cleveland star Napolean Lajoie was hitting .376 going into the final two games, but was losing in the batting title to Detroit Tigers outfielder Ty Cobb, who was hitting .385. Because Cobb was so hated at the time, Browns manager Jack O’Connor told his third baseman, Red Corriden, to position himself in shallow left field. Every time Lajoie came up to bat against the Browns, he bunted successfully down the third base time five consecutive times. During the sixth atbat, reached base on an error, which lowered his average. O’Connor and his coach, Harry Howell, sought to change the error to a hit by attempting to bribe the official scorer with a new wardrobe. Their efforts were reported to American League President Ban Johnson, who immediately ordered Browns owner Robert Hedges to fire both O’Connor and Howell, and then awarded the batting to title to Cobb. Both O’Connor and Howell were effectively banned from baseball for life. Jack O’Connor (above) and Harry Howell (right) 1914 World Series Upset • The four-game sweep of the Philadelphia Athletics by the Boston Braves in the 1914 World Series was stunning. • Students of that Series suspect that the Athletics were angry at their notoriously miserly owner, Connie Mack, and that the A's players did not give the Series their best effort. • Although such an allegation was never proven, Mack apparently thought that it was at least a strong possibility, and he soon traded or sold all of the stars away from that 1914 team. • Unfortunately for the decimated A's, within two years they had limped to the worst season won-loss percentage in modern baseball history (36-117 .235), and it would be well over a decade before they recovered. • Ban Johnson continually battled AL owners including his old ally Charles Comiskey. When Comiskey warned Johnson that his players may have been bribed to fix games for gamblers, Johnson ignored him. • Comiskey was a star player and manager in the 1880s and 1890s. He is sometimes credited with being the first 1B to play behind the bag and inside the foul line, which is common now. • He became the owner of the Chicago White Sox from 1900 until his death in 1931 and oversaw the building of Comiskey Park in 1910. • Notoriously frugal with his players, he made them pay to launder their own uniforms, hence the “Black Sox” nickname for their often dirty uniforms. • The substandard wages tempted many of his players to talk to gamblers about throwing games for money. After eight of his players were accused of throwing the 1919 World Series he provided them with expensive legal counsel. But ultimately supported the decision to ban them for life, despite the fact that it decimated his team by depriving them of its stars including “shoeless” Joe Jackson. Charles Comiskey 1917 World Series • The manner in which the New York Giants lost to the Chicago White Sox in the 1917 World Series raised some suspicions. • A key play in the final game involved Heinie Zimmerman (top left) chasing Eddie Collins across an unguarded home plate. Immediately afterward, Zimmerman (who had also hit only .120 during the Series) denied throwing the game or the Series. • Within two years, Zimmerman and his corrupt teammate Hal Chase would be suspended for life, not so much due to any one incident but to a series of questionable actions and associations. • The fact that the question of throwing the Series was even raised suggests the level of public consciousness of gamblers' potential influence on the game. 1918 World Series • In 1918 there were rumors of World Series fixing by members of the Chicago Cubs. • The Cubs lost the 1918 Series to the Boston Red Sox in a sparsely-attended affair that also nearly resulted in a players' strike demanding more than the normal gate receipts. • With World War I dominating the news (as well as Burns’ Baseball Clip: having shortened the regular baseball season and KenGambling in the Early Game having caused attendance to shrink) the 2:37 unsubstantiated rumors were allowed to dissipate. • • • • • One of the best players of his era, Chase’s career is tainted by fixing scandals. Beginning in 1910 he was accused of “laying down” in games by his own managers. Midway through the 1918 season, Chase, playing for the Reds, allegedly paid pitcher Jimmy Ring $50 ($729 today) to throw a game against the Giants. He was suspended for the season by the team but National League president John Heydler acquitted him due to lack of evidence. After the end of the 1919 season, an unknown individual sent Heydler a copy of a $500 ($6,349 today) check that Chase, now playing for the Giants, received from a gambler for throwing a game the previous season. Armed with this evidence, Heydler ordered Giants owner Charles Stoneham to release Chase. No American League team would sign him and he was effectively blackballed from the major leagues. On why he bet on baseball: "I wasn't satisfied with what the club owners paid me. Like others, I had to have a bet on the side and we used to bet with the other team and the gamblers who sat in the boxes. It was easy to get a bet. Sometimes collections were hard to make. Players would pass out IOUs and often be in debt for their entire salaries. That wasn't a healthy condition. Once the evil started there was no stopping it, and club owners were not strong enough to cope with the evil." Hal Chase (1919) • • • • 1919 Black Sox Scandal The 1919 World Series (often referred to as the Black Sox Scandal) is the most famous scandal in baseball history. Eight players from the Chicago White Sox (nicknamed the Black Sox) were accused of throwing the series against the Cincinnati Reds. Details of the scandal remain controversial, and the extent to which each player was involved varied. It was, however, front-page news across the country when the story was uncovered late in the 1920 season, and despite being acquitted of criminal charges (throwing baseball games was technically not a crime), the eight players were banned from organized baseball (i.e. the leagues subject to the National Agreement) for life. The “eight men out" were the great "natural hitter" "Shoeless" Joe Jackson; pitchers Eddie Cicotte and "Lefty" Williams; infielders "Buck" Weaver, "Chick" Gandil, Fred McMullin, and "Swede" Risberg; and outfielder "Happy" Felsch. Ken Burns’ Baseball Black Sox Scandal 27:52 “Shoeless” Joe Jackson • • • • • • • Juries acquitted Jackson of any involvement in the conspiracy in the criminal trial in 1921 and again in a 1924 civil suit that Jackson filed. In the latter, Jackson won a $16,711.04 judgment against White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. But Jackson, who hit a convincing .375 in the Series, setting a major league record for hits, did take $5,000 from a teammate after Game Four of the eight-game series. Some say that because Jackson refused to take the cash in his hand and a teammate simply left it on a table, for him. Jackson told a grand jury in 1920 that he’d accepted the money but hadn’t participated in any effort to lose a game. In the years after he was banned from baseball, Jackson started a barbecue restaurant in Greenville and later ran a liquor store. He never learned to read or write. He’s believed to have signed his name all of five times in his life — on his draft card, his driver’s license, his mortgage, a baseball and his will, which is in the museum. As the years went on Jackson rarely spoke about the scandal, but when he did, he contended that he had tried to report his suspicions about a fix to Comiskey, who allegedly rebuffed him. On his deathbed, Jackson declared just as he always had: “I’m innocent.” In 2005, Congress unanimously passed a resolution seeking Jackson’s reinstatement. Jackson’s famous bat, Black Betsy, was sold at auction in 2000 for almost $600,000. Ken Burns’ Baseball Commissioner’s Office Begins 5:53 The Commissioner • • • • • Hoping to restore public confidence in the sport following the 1919 Black Sox Scandal in which Chicago White Sox players accepted bribes from gamblers in order to throw the World Series, the owners named federal Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis commissioner of baseball, to replace the three-person National Commission that had formerly governed the sport. Landis accepted but on the condition that he have absolute power to take any action he deemed “in the best interest of baseball.” The owners agreed and Landis’ first decision was to ban the eight White Sox players involved in the scandal. Throughout 1921 Landis came under intense criticism for his moonlighting, and congressional members called for his impeachment. In February 1922, Landis resigned his position as a federal judge saying that, "There aren't enough hours in the day for me to handle the courtroom and the various other jobs I have taken on." Ban Johnson continually clashed with the new Commissioner and was ultimately forced out of baseball by the owners who also hoped that Landis would follow Johnson’s lead and that after the Black Sox scandal passed, Landis would “retire” to a quiet life as the titular head of baseball. But instead, Landis ruled baseball with an iron fist for 25 years. At times he antagonized the owners and the players but historians generally agree that his actions were consistent with his “best interest of baseball” mandate and the independence of the office. Claude Hendrix (1920) • • • • • Hendrix was a spitball pitcher for the Chicago Cubs and had pitched in the 1918 World Series, which was rumored to have been fixed. On August 31, 1920, Hendrix was scheduled to pitch against the Philadelphia Phillies. Cubs president Bill Veeck received telephone calls and telegrams saying Detroit gamblers were betting heavily that the Phillies, ranked at the bottom of the league, would beat the Cubs, a top team. The Cubs switched their rotation and went with their better pitcher, Grover Cleveland Alexander, instead but still ended up losing the game. A grand jury was convened in Chicago to investigate the incident, and during the course of the investigation the Black Sox scandal emerged. Needless to say, the grand jury never ruled on whether the Cubs/Phillies game was linked to gambling. Hendrix’s career was on a downturn in 1920 and he had announced his retirement at the end of the season, while the grand jury was still convened. In February 1921, the Cubs gave him an unconditional release and Veeck issued a statement that Hendrix’s release had nothing to do with events of 1920, alluding to the Cubs/Phillies game and the rumors that had circulated. Commissioner Landis never banned Hendrix. But that’s been the popular belief because Landis’ 1947 biography made the false claim. “Shufflin’” Phil Douglas (1922) • In 1922 New York Giants pitcher, and former Chicago Cub, Phil Douglas sent a strange letter to former Cubs teammate Les Mann, who was then with the Cardinals, one of the teams battling the Giants for the pennant. • Douglas proposed that he would quit the team if Mann and his teammates came up with, “the goods.” “So you see the fellows,” Douglas wrote, “and if you want to send a man over here with the goods, and I will leave for home on the next train, send him to my house so nobody will know, and send him at night.” • Douglas, it seemed, was trying to throw the pennant race. • Mann turned the letter over to his manager, Branch Rickey, who passed it on to Commissioner Landis. • After meeting with McGraw, Landis banned Douglas from baseball. The O’Connell-Dolan Scandal (1924) • • • • • • • The Giants and Dodgers were battling for the 1924 National League championship. As the last weekend arrived, the Giants had a 1 ½ game lead in the standings with three home games against the lowly Phillies. The Dodgers had two games left with the even more lowly Braves and should they win both and the Giants lose both, the Dodgers would take the division. Before the Giants-Phillies game of Saturday, September 27, Giants utility outfielder Jimmy O'Connell, at the instigation of Coach Cozy Dolan, sounded out Phillies shortstop Heinie Sand as to whether, for $500, he might be willing to avoid "bearing down hard." Afterwards, O'Connell also contended that Giant stars Frankie Frisch, Ross Youngs, and George Kelly had spoken with him before the game about the feeler. At any rate, Sand rejected O'Connell's invitation. Growing worried during the course of the game, Sand that evening reported the bribe offer to his manager, Art Fletcher. The latter immediately took the matter to the, executive level and soon Commissioner Landis was involved. Hearings were promptly held at which O'Connell, Dolan, Sand, Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs testified. O’Connell and Dolan were banned while Sand was booed by fans for being a squealer for years until he left the game. Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs—3 future Hall of Famers—were likely behind the incident, testified that they were simply kidding, and were not sanctioned. Jimmy O’Connell Cozy Dolan The Cobb-Speaker Incident (1926) • • • • • • Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker were permitted by American League President Ban Johnson to resign from baseball near the end of the 1926 season after former pitcher Dutch Leonard charged that Cobb, Speaker and Smoky Joe Wood had joined him just before the 1919 World Series in betting on a game they all knew was fixed. Leonard presented letters and other documents to Johnson, and Johnson thought they would be so potentially damaging to baseball in the wake of the Black Sox scandal that he paid Leonard $20,000 to have them suppressed. Commissioner Landis exposed the cover-up and the eventual fallout forced Johnson out his job as president of the league he had created. Cobb and Speaker vehemently denied any wrongdoing, Cobb saying that "There has never been a baseball game in my life that I played in that I knew was fixed,” and that the only games he ever bet on were two series games in 1919, when he lost $150 on games thrown by the Sox. He claimed his letters to Leonard had been misunderstood, that he was merely speaking of business investments. Landis took the case under advisement and eventually let both players remain in baseball because they had not been found guilty of fixing any game themselves. It was after this case, though, that Landis instituted the rule mandating that any player found guilty of betting on baseball would be suspended for a year and that any player found to have bet on his own team would be barred for life. Cobb later claimed that the attorneys representing him and Speaker had brokered their reinstatement by threatening to expose further scandal in baseball if the two were not cleared. Leo Durocher Suspension (1947) • After the scandals of the 1920s it appeared that baseball’s gambling problem had been solved. • In 1947 Leo Durocher, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, became involved in a feud with New York Yankee owner Larry MacPhail (top left)— each accusing the other of inviting gamblers into the clubhouse. • Commissioner Happy Chandler was under pressure from MacPhail, a close friend who was pivotal in having him appointed to succeed Landis as Commissioner. • Chandler first warned Durocher and then suspended him for the 1947 season after he discovered evidence that Durocher and actor George Raft were running rigged crap games in order to take money from unsuspecting players. • Commissioners have always taken an almost fanatical interest in gambling, suspending wellknown individuals for lengthy times just for having been seen with gamblers. Denny McLain: The Rise (1968-1969) • • • In 1968 Detroit Tigers pitcher Denny McLain won 31 games (the last pitcher to do so), the Cy Young and MVP awards, and led his team to a World Series championship. He became famous, racked up endorsements, did TV appearances, and won 24 games and the Cy Young the following year. In February 1970, Sports Illustrated and Penthouse both published articles about McLain's involvement in bookmaking activities. Sports Illustrated cited sources who alleged that the foot injury suffered by McLain late in 1967 had been caused by an organized crime figure stomping on it for McLain's failure to pay off on a bet. Early in his career, McLain’s interest in betting on horses was piqued by Chuck Dressen, one of his first managers. McLain’s descent into his gambling obsession was further precipitated by an offhand remark made during an interview: that he drank about a case of Pepsi a day. (When he pitched, he was known to drink a Pepsi between innings.) A representative from Pepsi then offered McLain a contract with the company, just for doing a few endorsements. McLain soon realized that he and the Pepsi rep shared an affinity for gambling; when the two realized how much money they were losing, and that they could earn so much more by "taking the action" on bets, they attempted to set up a bookmaking operation as hands-off, silent partners. Denny McLain: The Fall (1970) • • • • McLain was suspended indefinitely by Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn; the suspension was then set for the first three months of the1970 season. He returned in mid-season, but struggled to pitch well. He received a seven day suspension in September for dousing two sportswriters with buckets of water. Just as the seven day suspension was about to end, he received another suspension from Kuhn for carrying a gun on a team flight that effectively ended his season. Later that year, despite being the first $100,000 player in Tigers history, he was forced into bankruptcy, traded, had arm trouble, traded again and again, and was out of baseball by the age of 29. McLain’s troubles didn’t end there, however. He was imprisoned for drug trafficking, embezzlement and racketeering, spending a good portion of the 1980s and 1990s behind bars. Mickey Mantle Ken Burns’ Baseball Mickey Mantle 8:43 Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays Banned (1983) • After their retirement, Hall-of-Famers Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays were no longer involved in Major League Baseball. • In 1983 they were hired by casinos in Atlantic City, New Jersey, for public relations: to be greet guests and autograph signers. • Mantle was hired by the Claridge Hotel and Casino to become their goodwill ambassador, and Mays held a similar position at Bally's Park Place. • Commissioner Bowie Kuhn banned them from baseball saying that any affiliation with gambling were grounds for being placed on the "permanently ineligible" list. He added that a casino was "no place for a baseball hero and Hall of Famer." • Newspaper articles of the time pointed out that Mantle and Mays played before there were large player salaries and that they were simply trying to make money to live. • Their bans were finally lifted in 1985 during Commissioner Peter Ueberroth's tenure. The Steinbrenner-Winfield Feud (1990) • • • • • • Ken Burns’ Baseball Steinbrenner 7:33 In late 1980, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, who had already developed a reputation for spending lavish amounts of money on free agents, signed Dave Winfield to a 10-year, $23 million contract. In 1985, Steinbrenner referred to Winfield as “Mr. May,” in an interview with New York Times reporter Murray Chass after a late September series against the Toronto Blue Jays, saying, “Where is Reggie Jackson? We need a Mr. October or a Mr. September. Winfield is Mr. May. My big guys are not coming through. The guys who are supposed to carry the team are not carrying the team. They aren't producing. If I don't get big performances out of Winfield, (Ken) Griffey and (Don) Baylor, we can't win.” In July 1990, after Winfield had sued the Yankees for not making a $300,000 contribution to his charitable foundation as stipulated in his contract. Steinbrenner hired Howie Spira, a known gambler, and paid him $50,000 to dig up whatever “dirt” he could find about Winfield. Word of this got back to MLB commissioner Fay Vincent, who suspended Steinbrenner from baseball for a period of two years. In Steinbrenner's absence, his son took control of the Yankees, and then relinquished the team back to his father when Bud Selig reinstated him in 1993. Steinbrenner retired as owner in 2006, passing control to his sons permanently and died in 2010. Pete Rose Ken Burns’ Baseball Charlie Hustle 2:07 Big Red Machine 2:01 Rose Breaks Record 1:43 Rose Banned 5:32 Pete Rose Betting Scandal (1989) • • • • • Pete Rose, baseball's all-time leader in hits and games played and manager of the Cincinnati Reds since 1984, was reported as betting on Major League games, including Reds games while he was the manager. Rose had been questioned about his gambling activities in February 1989 by outgoing Commissioner Peter Ueberroth and his successor, National League president A. Bartlett Giamatti. Three days later, lawyer John M. Dowd was retained to investigate the charges against Rose. During the investigation, Giamatti took office as the Commissioner of baseball. A March 21, 1989 Sports Illustrated article linked him to gambling on baseball games. The Dowd Report asserted that Pete Rose bet on fifty-two Reds games in 1987, at a minimum of $10,000 a day. It included testimony that Rose had bet on his own players while managing, phone records to known bookies moments before ball games (while no other major sports were in season) and a betting slip filled out in Rose's handwriting and covered with his fingerprints. Pete Rose Betting Scandal (1989) • Rose, facing a very harsh punishment, along with his attorney and agent, Reuven Katz, decided to seek a compromise with Major League Baseball. On August 24, 1989, Rose agreed to a voluntary lifetime ban from baseball. The agreement had three key provisions: • Major League Baseball would make no finding of fact regarding gambling allegations and cease their investigation; Pete Rose was neither admitting or denying the charges; and Pete Rose could apply for reinstatement after one year. • To Rose's chagrin, however, Giamatti immediately stated publicly that he felt that Pete Rose bet on baseball games. • Then, in a stunning follow-up event, Giamatti, a heavy smoker for many years, suffered a fatal heart attack just eight days later, on September 1. Aftermath: Pete Rose Banned for Life • • • • • • • The consensus among baseball experts is that the death of Giamatti and the ascension of Fay Vincent, a great admirer of Giamatti, was the worst thing that could happen to Pete Rose's hopes of reinstatement. On February 4, 1991, the twelve members of the board of directors of the Baseball Hall of Fame voted unanimously to bar Rose from the ballot. However, he still received 41 write-in votes on January 7, 1992. Bud Selig, the former owner of the Milwaukee Brewers, succeeded Vincent in 1992. Rose was allowed to be a part of the All-Century Team celebration in 1999 as he was named by the fans as one of the team's outfielders. He appeared with all the other living selected players before Game 2 of the 1999 World Series. Rose applied for reinstatement in September 1997 and March 2003. In both instances, Commissioner Selig failed to act, thereby keeping the ban intact. In 2004, after years of speculation and denial, Pete Rose admitted in his book My Prison Without Bars that the accusations that he had bet on Reds games were true, and that he had admitted it to Bud Selig personally some time before. Rose, however, stated that he always bet on the Reds — never against. Should Rose be reinstated to baseball and be eligible for the Hall of Fame? Conclusion • Gambling has been a part of the game since its inception. • Early players said that they gambled due to low salaries. • Modern players have gambled for other reasons. • Whatever the reason, in the quest for greater profits, baseball has been extremely strict in penalizing those associated with gambling. References • • • Fisher, Marc. 2012. “At the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum iin Greenville, S.C. It Ain’t So.” Washington Post.February 3. Ginsburg, Daniel E. 1995. The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.). Longoria, Rico. 2001. “Baseball’s Gambling Scandals.” ESPN.com, July 30.