Understanding Character

advertisement

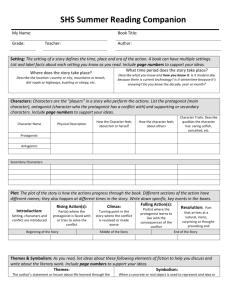

Character Many writers will tell you that a story depends on its characters, rather than the actual plot. Some even say that if you create interesting characters and give them a scenario, they will take over and “write” the story. At the very least, characters must be believable for a story to ring true, and writers bring them to life in specific ways. First, it is important to understand basic terminology involving character. The main person in a story is called the protagonist; if the protagonist is in conflict with another character or force, the opposing character or force is called the antagonist. A foil is a character who serves, by contrast, to highlight the characteristics of another character. Ex. Antagonists are usually people, but could be something like the whale in Moby Dick, the weather in The Perfect Storm, society as a whole, or even conflicting desires within the protagonist. Ex. A wicked character in a literary work can serve as a foil to one who is at least reasonably upstanding. A very meek character may be the foil of an independent character. Major characters are important to a story, while minor characters play less important roles. Characters can be described as round or flat—round if they are fully developed, flat if readers see only one side of them (one or two character traits). Ex. A “loyal wife” who is only heard or seen being loyal to her husband would be considered flat even if she is in a number of scenes. Although in reality a wife would have numerous other traits, the author only needs to show this wife being loyal for purposes of the story. Recognizable character “types” may be called stock characters or stereotypes (often unfairly negative). Ex. The strong-but-silent cowboy, the mad scientist, the battle-scarred veteran, and the dumb jock are all examples of stock or stereotypical characters. Characters can also be described as dynamic or static—dynamic if they change during the course of the story, static if they do not. It is important to realize that these terms are used in order to discuss literature. They are not mutually exclusive, meaning that a protagonist may be both round and dynamic (or even static occasionally). A foil may be classified as both a flat and stock character. Of course, a character cannot logically be two opposites, such as both flat and round. Understanding Characterization Writers reveal their characters in six basic ways, one direct, five indirect: Direct statement: The author can tell readers that a character is, for example, “a foolish man,” or that “she had a cool head under pressure.” Indirect methods include: Description of the character’s appearance and his/her background, surroundings, possessions Narration of the character’s actions Narration of the character’s thoughts Narration of the character’s words Record of others’ reactions toward the character – how do they behave and/or what do they say about the character? The indirect methods require the reader to infer certain things about the character by putting these details together. Combined with the direct statements, if any, a definite personality should emerge. Writing About Character Armed with above knowledge, students can analyze characters in all genres (novels, short stories, plays, poems). Here are some possible topics for writing about character: 1. Analyze how the protagonist or antagonist changes from the beginning of the work to the end. 2. Analyze the role of a minor character (or characters) in a literary work. 3. Discuss the role of foils in a literary work. 4. Discuss the conflicts, internal and external, that a character suffers. 5. Analyze the use of a character as narrator. 7. Discuss the use of dialogue as a method of characterization. 8. Explain a character’s class or place in society. Is the character free to move within several classes or limited to one? Why? 9. Explain the role the character has played so far in the novel (importance). 10. Explain how the character reflects the values of the time period in which the work was written. 6. Compare and/or contrast two of the characters. Evaluate relationships between/among characters. The Scarlet Letter—Character Analysis Directions: For this week’s reading, focus on one or two characters that seem to be significant to the plot, conflict, theme, etc. Review the notes from Understanding Characterization and Writing About Character and select three quotes that highlight the character/s. Write the quotes in MLA format and then provide at least 3-5 sentences of commentary explaining the significance of the details in relation to the character. You will have three separate quotes and three separate paragraphs of commentary.