DefectsofconsentchapterFINAL

advertisement

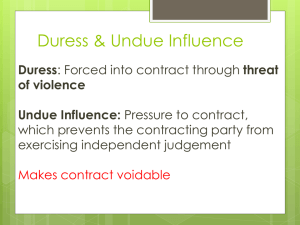

Defects of consent in English law: protecting the bargain? Introduction In English law, a voluntary and free consent is clearly regarded as an essential requirement for a valid contract. Doctrines therefore exist in law and equity to protect against defective consent, but these have developed in a piecemeal fashion1. A party’s consent may consequently be defective in the event that the party was mistaken, deceived or threatened by the other contracting party (or even a third party).2 Defective consent is usually seen through the prism of the dichotomy between party autonomy and the sanctity of contract. The question is however wider than that, since defects of consent not only raise issues of fairness but also relate to more general conceptions of justice3. In fact, as highlighted by Professor Harrison in this book, 1 The lack of a unified theory of defects of consent is explained by historic and systemic considerations: see Muriel Fabre-Magnan and Ruth Sefton-Green, ‘Defects of Consent in Contract Law’ in Arthur S Hartkamp et al (eds), Towards a European Civil Code (3rd edn, Kluwer Law International 2004) 399, 406. 2 For an interesting comparative study in this field, see Gareth Sparks, Vitiation of Contracts: International Contractual Principles and English Law (CUP 2013). 3 The approach of a legal system to defects of consent reveals much about the system’s approach to contracts: John Cartwright, ‘Defects of Consent in Contract 1 discussions about consent are ‘less about consent as an absolute matter than about the quality of consent’.4 A proper enquiry therefore requires us to delve into the underlying policy and purpose of the doctrines and consider how these piecemeal solutions are used. Do vitiating factors simply aim to protect against such defects of consent in the light of the general theory of voluntariness?5 Or do they reflect other values such as protecting the victim, usually the weaker party, from a contractual imbalance?6 If so, are they justified by reference to procedural fairness or can they also intervene in order to achieve substantive fairness? The debate over the relation between defects of consent and fairness is still highly relevant. Indeed, following the increasing specialization of contracts (following, in great part, the Europeanisation of consumer contracts) and new developments in the law7, the question of the role of and place for defects of consent must therefore be Law’ in Arthur S Hartkamp, Towards a European Civil Code (4th edn, Kluwer Law International 2011) 537, 537. 4 See ch 000, p 000 [Ref to Harrison ch]. 5 In favour of this, see Sparks (n 2) ch 1. 6 This is especially the case where consent was induced by unacceptable conduct, as in duress, undue influence. Many have called for a formal review of the law: see, eg, Mindy Chen-Wishart, Contract Law (4th edn, OUP 2010) ch 8; David Capper, ‘Protection of the vulnerable in financial transactions: what the common law vitiating factors can do for you’ in Mel Kenny, James Devenney, and Lorna Fox O’Mahony (eds), Unconscionability in European Financial Transactions (CUP 2010). 7 Fabre-Magnan and Sefton-Green (n 1) 407. Two EU texts in particular highlight the need to assess the role and place of defects of consent, the Council Directive (EC) 2 considered. That is the aim of this chapter, which is organized in two parts: the first part will critically consider the law on capacity and duress in order to assess their role and efficiency (consistency in protection and efficiency in relief) of such systems; the second part will consider the role of and place for defects of consent in the wider context of the Europeanisation of (consumer) contract law, as well as their future. A critical look at some defects of consent under English law Even though the UK does not have a unitary doctrine of defects of consent, the English approach is nevertheless coherent8. The various doctrines can be categorised into two types of defects, those that negate consent (capacity, mistake and misrepresentation) and those that impair consent (duress, undue influence and unconscionable bargains)9. This chapter will concentrate on capacity and duress (with reference to undue influence and unconscionability) in order to assess the link between procedural and substantive fairness in those fields. Capacity 2005/29 on unfair commercial practices [2005] OJ L 149/22) for duress. The recognition of duties of disclosure as part of a larger field of pre-contractual liability and that of Consumer Rights Directive (EC) 2011/83, [2011] OJ L 304/64 is relevant for misrepresentation. The first issue will be discussed in the second part of this chapter. 8 Fabre-Magnan and Sefton-Green (n 1) 402. 9 For Sparks, this is all linked to the doctrine of voluntariness. For his central theory, see Sparks (n 2) ch 1. 3 The issue of capacity raises the difficulty of having to reach a compromise between two competing policies of (on the one hand) protecting people of unsound mind but (on the other) without causing too much detriment to the people with whom they have dealt in a fair manner10. In spite of the introduction of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, the rules have not changed substantially11 and the Act certainly does not remove the above-mentioned need for a compromise between competing policies. As such, the rules can therefore still be described as deceptively simple12. Issues of capacity typically arise in two situations: (1) when the inequity is suffered by the person of unsound mind himself, or (2) when it is suffered by a person outside the contract. In relation to the former, at common law, and following the objective theory of contracting, it is not possible to set aside a contract for mental incapacity alone, since the incapacity must be known to the other contracting party13. Where the other party is not aware of the incapacity, following the seminal decision of the Privy 10 Ewan McKendrick, Contract Law (10th edn, Palgrave Macmillan 2013) 287. 11 The act is based upon a presumption of capacity, s 1(2) stipulating that a person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that he does not. 12 Professor Chen-Wishart says that ‘although an incapacitated party is logically incapable of giving valid consent … the actual picture is far messier’: Chen-Wishart, (n 6), additional online chapter http://global.oup.com/uk/orc/law/contract/chenwishart4e/, accessed 10 July 2013. 13 Imperial Loan Co v Stone [1892] 1 QB 599. For drunkenness, the same principle applies: see Gore v Gibson (1843) M&W 623. 4 Council in Hart v O’Connor14, the contract can only be set aside if, using equitable standards, the contract is unconscionable. As in the US, capacity is therefore most relevant when the inequity is suffered by a third party. As also in the US, this is most often the case in family testamentary disputes. The questions of whether the balance of exchange influences the decision and whether the courts have a paternalistic attitude are very interesting ones in that area. Indeed, it is clear from Banks v Goodfellow15, the leading case on testamentary capacity, that although testators have ‘an unfettered discretion’16 in the disposal of their property, it is nevertheless conditional upon the testator having capacity. The test, as defined by Cockburn CJ, which has withstood the test of time is as follows: it is essential … that a testator shall understand the nature of the Act and its effects, shall understand the extent of the property of which he is disposing; 14 [1985] AC 1000 (PC). In this case, a piece of land was sold to the defendant. Unknown to the defendant, the seller was of unsound mind. Shortly after the sale, the defendant started farming the land and carried out improvements to it. The plaintiffs (the brother of the seller and his two sons) instituted proceedings in New Zealand on the ground of the mental incapacity of the seller, unfairness, and unconscionability. At first instance, and on appeal to the Court of Appeal of New Zealand, the contract was set aside for want of capacity and for unfairness. The Privy Council however reversed both judgments, on the ground that it was impossible to set the contract aside simply because it was unfair to the person of unsound mind. 15 (1870) LR 5 QB 549. 16 Goodfellow 563 (Cockburn CJ). 5 shall be able to comprehend and appreciate the claims to which he ought to give effect; and, with a view to the latter object, that no disorder of the mind shall poison his affections, pervert his sense of right, or prevent the exercise of his natural faculties—that no insane delusion shall influence his will in disposing of his property and bring about a disposal of it which, if the mind had been sound, would not have been made.17 Capacity aside, testamentary freedom must also be appreciated in the context of ‘a moral responsibility of no ordinary importance’18 which, as Cockburn CJ adds ‘will lead men to make provisions for those who are the nearest to them in kindred and who in life have been the object of their affection’.19 In other words, the normal thing to do is for parents to leave their estate to those closest to them, their children. When they do not, the will is regarded as ‘surprising’ or ‘unofficious’20. This is the area, which is the most interesting to us, since issues of fairness are therefore relevant for the courts when assessing capacity. Although the courts have discretion, they nevertheless use it in a very cautious manner so as to not to be seen to be paternalistic. In the words of Lord Neuberger, ‘a court should be very slow to find that a will does not represent the genuine wishes of the testatrix simply because its terms are surprising, inconsistent 17 Goodfellow 565. 18 Goodfellow 563. 19 Goodfellow 563. 20 Goodfellow 570. 6 with what she said during her lifetime, unfair or even vindictive or perverse’.21 The balance is therefore delicate since the question for the courts is not ‘whether the will is a fair one in all the circumstances of the case’22 but ‘if the provisions of the will are surprising, that may be material to the court’s assessment of whether the testator did have capacity’23. The courts therefore have to try to balance the policy considerations behind the testamentary freedom24 with issues of fairness. As to the manner in which the courts assess this unfairness, the position was well summarized by May LJ in Sharp and Bryson v Adam and Adam and others,25 who stated that ‘an irrational, unjust and unfair will must be upheld if the testator had the capacity to make a rational, just and fair one, but it could not be upheld if he did not’.26 In this instance, Adam suffered from multiple sclerosis and died a short time after making his last will in 2001, in which will he disinherited his two daughters and left the bulk of his estate to the 21 Gill v Woodall and others [2011] 3 WLR 85, [26] (Lord Neuberger) (note however that this was not a case on capacity). For a similar remark in a case on capacity, see Sir James Hannen, in Broughton v Knight (1873) LR 3 P&D 64, 66, who stated ‘the law does not say that a man is incapacitated from making a will if he proposes to make a disposition of his property moved by capricious, frivolous, mean or even bad motives’. 22 Cowderoy v Cranfield [2011] EWHC 1616, [133] (Morgan J). 23 Cowderoy [133] (Morgan J). 24 Gill v Woodall and others [2011] 3 WLR 85, [86]. 25 [2006] EWCA Civ 449. 26 Sharp and Bryson [79]. 7 appellants, who had been looking after him for years. His daughters, the first two respondents, claimed that the 2001 will was invalid on the ground that their father lacked capacity. They claimed that a previous will, made in 1997, which treated them as the main beneficiaries of the estate, should therefore be reinstated. By 2001, Adam was in a very debilitated state and could neither speak nor read, communicating through a mixture of spelling board, eye movement, and shaking of the head. There was competing expert evidence as to his testamentary capacity. Applying the Goodfellow test, the Court of Appeal found that, as the disinheritance of the daughters could not be explained rationally (there being no family dispute), the testator lacked capacity in 2001. The freedom to make an ‘unfair will’ is therefore respected so long as it is a rational decision; if that is the case, capacity cannot be contested, as the more recent case of Jeffery & Anor v Jeffery27 illustrates. In this case, the court held the testatrix’s decision to disinherit one of her sons, Nicholas, to be perfectly capable. The testatrix had been running an insurance business with her husband. This business was subsequently handed over to Nicholas, who ran it in a fraudulent manner. On discovering this, the testatrix changed her will to disinherit Nicholas. He later challenged the will on the ground of his mother’s competency (as well as undue influence on the part of his brother, Andrew, a ground that was not established). Vos J, in finding that the testatrix was perfectly capable, considered that the fraud was a strong and valid reason to disinherit her son28. The court also took into consideration 27 [2013] EWHC 1942 (Ch). 28 Jeffery [239], finding (ix). 8 the fact that, as she had nevertheless provided for her son’s children, she clearly had capacity.29 A similar position was adopted in Cowderoy v Cranfield30 where the decision by a grandmother (Mrs Blofield) to disinherit her granddaughter (the claimant) in favour of the defendant, who had looked after her when she was dying of cancer, did not demonstrate a lack of capacity. The court emphasized that the granddaughter’s contestation of the will was primarily motivated by her distrust of the defendant and by her own interest as the sole beneficiary in an intestacy31. It therefore seems that 29 Jeffery [239], finding (ix). See too, Wharton v Bancroft [2011] EWHC 3250 (Ch), where Mr Wharton, who was in the last stage of cancer, married the woman whom he had lived with for 32 years having made a will leaving his entire estate worth £4m solely to her, and leaving nothing to his daughters (contrary to an earlier will). 30 Cit n 22. 31 Cowderoy [116]. Undue influence was also pleaded, but not established. Undue influence, is very often pleaded in addition to incapacity, since similar issues— namely whether the consent was free or was influenced by a relationship—are raised. This is especially relevant in cases of gift: see, eg, De Wind v Wedge [2008] EWHC 514 (Ch), concerning a brother and sister treated differently by their mother in her will. The gift was in favour of the brother (who had power of attorney), and the sister contested the will on the ground of undue influence. The court rejected her claim, finding no undue influence, and holding that the gift of the mother to the brother had been given of her own free will, without persuasion on his part. The gift was motivated by the fact that, a few years previously, the brother had loaned £70,000 to his sister to allow her to start a business in Spain. The primary reason for the gift was 9 when assessing fairness, the courts have regard to the character of the parties. In Cowderoy, Mrs Blofield had an alcoholic son who, in his latter years, came to live with her. The defendant was well known to Mrs Blofield as he had been a drinking partner for her son for some years. Although Mr Cranfield’s house was close to that of Mrs Blofield’s the former nevertheless spent considerable time at her house. When Mrs Blofield’s son died, Mr Cranfield continued to visit her. When she was too diagnosed with terminal cancer, Mr Cranfield helped her till her death. The judge emphasized that whereas Mr Cranfield had underplayed everything that he had done for Mrs Blofield, the granddaughter’s sole interest in challenging the will was financial. Mrs Blofield’s desire to leave her estate to Mr Cranfield was motivated by a clear wish not to leave anything to her granddaughter as well as by the hope that in doing so, Mr Cranfield would continue to come and care for her, she was clearly capable.32 A final point to make is that, although the courts apply the Goodfellow rule in the same manner whether the will is to benefit other relatives or strangers (the latter in the form of natural or legal persons), the further removed from the testator the beneficiaries are, the closer the scrutiny appears to be. This is especially so when the sums involved are high, as the cases of Re Kostic, Kostic v Chaplin33 and Gill v Woodall34 demonstrate. In the Kostic case, which involved insanity, the testator had that the money loaned had not been reimbursed. The UK and American positions on such cases are strikingly similar: see p 000 of this work [ref Harrison, part IV, A]. 32 Cowderoy [147] (Morgan J). 33 [2007] EWHC 2298 (Ch). 34 [2010] EWCA Civ 1430, [2011] Ch 380, [2011] 3 WLR 85. 10 left his entire estate (worth £8.2m) to the Conservative Party rather than his only son. The court went to some considerable length to establish incapacity. The case of Gill, involving an estate worth over £1m, though not a capacity case, nevertheless appears to show a similar tendency towards the perceived sense of injustice where the parent disinherits a child for, seemingly, no valid reason. In this case, the issue was whether the testatrix had known and approved of the contents of the will, which, having been prepared on the instructions of her husband some years earlier, left her entire estate to the RSPCA rather than to her only daughter. Lord Neuberger went to some length to reiterate the exceptional nature of the facts (and therefore the appeal) of the case,35 stressing that the decision was not to be seen as ‘a green light to disappointed beneficiaries’.36 Yet, given the exceptional nature of the facts, the court held that the testatrix did not know the contents of her will. The decision was therefore in the daughter’s favour. In this instance, the unfairness of the will appears to have played a crucial role in the court’s decision. Emphasis was laid by the court on the fact that the relationship between mother and daughter was absolutely fine, the decision to leave the estate to the RSPCA seemingly coming rather out of the blue given the view of the mother towards the beneficiary,37 and on the fact that, as the daughter (and her husband) had considerably helped out on the farm her parents owned, not to leave the estate to her created a sense of unfairness. It is clear that, in testamentary matters, incapacity as a vitiating factor is an important tool giving the courts some discretion to avoid what can sometimes be described as an 35 Gill [65] (Neuberger LJ). 36 Gill [65] (Neuberger LJ). 37 For details, see Gill [29]. 11 unfair outcome. Although the courts are at pains to emphasise that their primary task is ‘to ascertain what was the last true will of a free and capable testator’,38 and not to decide ‘whether the will is a fair one in all the circumstances of the case’,39 the process by which they do so is nevertheless in response to ‘indignations at a sense of unfairness’.40 This appears especially so when the sums are very large and the beneficiaries far removed from the deceased. On this, the position in the UK is strikingly similar to that of the US. (Economic) Duress Contract law has always placed limits on the permissible means used to persuade another.41 At first sight, duress, as a doctrine,42 would therefore appear ideally placed 38 Wharton v Bancroft [2011] EWHC 3250, [8] (Norris J). 39 Cowderoy [133] (Morgan J). 40 Wharton [9] (Norris J). 41 Chen Wishart (n 6) 313. 42 The fact that there is a unitary doctrine of duress is contested, given the existence of three forms of duress, duress to the person (Barton v Armstrong [1976] AC 104), duress to goods (The Evia Luck [1991] 4 All ER 871), and economic duress: Capper (n 6) 173. Sparks, far from seeing this as a problem, states that this allows the adoption of a sliding scale, similar to that of misrepresentation, based on the illegitimacy of the defendant’s conduct with economic duress the least serious: Sparks (n 2) 212. 12 to regulate certain aspects of unfairness.43 However, as the focus is on procedural fairness, the courts do not, traditionally, use duress to alter substantive outcomes. This is due, of course, in no small part to the link with consideration.44 And yet, as in the US, substantive fairness (or a sense of perceived unfairness by the judiciary) nevertheless appears relevant. This is especially so in relation to the emerging doctrine of economic duress,45 where the link between duress and unfairness appears stronger than with capacity and unfairness (or, at the very least, more openly acknowledged46). However, in spite of recent developments in the field, which show interesting tempering of the non-interference rule, the doctrine is still ‘emerging’,47 43 For a contrary view, see Capper (n 6), 173, who thinks that duress tends to operate outside the relational context, where vulnerable people are in most need of protection, ie in relation to undue influence. 44 45 Consideration need not be adequate but must be sufficient in the eyes of the law. Although still a reasonably new doctrine (it first arose in Occidental Worldwide Investment Corporation v Skibs A/S Avanti (the Siboen and the Sibotree) [1976] 1 Lloyds’ Rep 293), economic duress is the most significant form of duress, hence, the focus on it in this chapter. 46 See Coleman J’s comments in South Caribbean Trading Ltd v Trafigura Beheer BV [2004] EWHC 2676, [2005] 1 Lloyds Rep 128, [112], that ‘economic duress (…) is (…) based on principles of unconscionability which can be seen as principles of fairness’. 47 Sapporo Breweries Ltd v Lupofresh Ltd [2012] EWHC 2013, [50] (Bean J). On appeal, the Court of Appeal held that Japanese law was applicable and, as there was no doctrine of duress under Japanese law, the plea could not succeed: [2013] EWCA Civ 948. 13 and still suffers from ‘conceptual confusion’.48 Its precise scope and role are consequently difficult to identify, which significantly weaken its impact. Interestingly, although the US position is not perfect either, the problems the US face are of a different nature49. For a successful plea of economic duress to succeed, two elements must be established, (1) an illegitimate pressure,50 and (2) causation. Although the two are inextricably linked51, what amounts to an ‘illegitimate’ pressure, especially in a commercial setting, and the correct test for causation are both far from obvious. On the question of the legitimacy or otherwise of the pressure, it is plain that ‘illegitimate pressure must be distinguished from the rough and tumble of the 48 For Mckendrick (n 10) para 17.2. See too Capper (n 6), 182, who proposes to merge duress with undue influence and unconscionable bargains, on the ground of the lack of theoretical coherence to economic duress. 49 See p 000 of this work [ref to Harrison ch]. 50 Lord Hoffmann stated, in R v AG for England and Wales [2003] UKPC 22, [2003] EMLR 24, that, in the ‘wrong of duress’, there are two elements: pressure amounting to the compulsion of the will, and the illegitimacy. 51 In Huyton v Peter Cremer [1999] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 620, Mance J remarked (637) on ‘the extent to which any consideration of causation in economic duress inter-acts with consideration of the concept of legitimacy’. Bigwood asserts that the rationale of vitiation is the interaction of the illegitimacy of the pressure (the unacceptable conduct) and the impairment of the complainant following the pressure: Rick Bigwood, Exploitative Contracts (OUP 2003) 291-4. 14 pressures of normal commercial bargaining’52 and that the question depends on the nature of the threat and on the demand.53 Yet, as the courts are wary of providing a broad definition, and consequently apply a wide range of factors when considering the legitimacy/illegitimacy of the pressure54, a clear concept of legitimacy has yet to emerge. This is problematic especially in relation to the conduct/motive of the wrongdoer, which brings broad notions of fairness but makes it difficult to ascertain whether the essence of the relief is based on the conduct of the wrongdoer or the adequacy of the consent55. That very problem was recently raised in the context of 52 DSND Subsea v Petroleum Geo-Services [2000] EWHC 185 (TCC), [2000] BLR 530, 545 (Dyson J). See too deputy judge David Donaldson QC, in Adam Opel GmbH v Mitras Automotive (UK) Ltd [2007] EWHC 3205 (QB), who stated that the fundamental question is whether the pressure has crossed the line ‘from that which must be accepted in normal robust commercial bargaining’([26)]. 53 Universe Tankship Inc of Monrovia v International Transport Workers Federation [1983] 1 AC 366, 400-401 (Lord Scarman). 54 Dyson J in DSND stated ([131]) that there were 5 factors, namely (1) whether there has been an actual or threatened breach of contract, (2) whether the person allegedly exerting pressure has acted in good or bad faith, (3) whether the victim had any realistic practical alternative but to submit to the pressure, (4) whether the victim protested at the time, and (5) whether he affirmed and sought to rely on the contract. Such factors were reiterated in Carilion Construction Ltd v Felix (UK) Ltd [2001] BLR 1, and were approved in the Adam Opel case. For Professor McKendrick, these factors, although flexible, are uncertain and link things that should be kept separate. McKendrick, (n10), p 296. 55 Capper (n 6) 172. 15 ‘lawful acts of duress’, where what the courts perceive to be immoral conduct on the defendant’s part will be punished. That much is very clear in the Privy Council decision of Borrelli v James Ting,56 where it was held that economic duress can include an action ‘not made in good faith’, motivated ‘for an improper motive’,57 and therefore amounting to ‘unconscionable conduct’.58 The case arose out of the collapse and eventual windingup of Akai Holdings Ltd in 1999. Following Ting’s constant refusal to help the liquidators in their attempt to realize the assets of the group59, in 2002 the liquidators accepted a Settlement Agreement under which Ting agreed to withdraw his opposition to the scheme of arrangement and the liquidators agreed not to pursue any claims against Ting and to stop all investigations against him60. After the scheme of agreement was completed, the liquidators sought orders to examine Ting, who then commenced proceedings in Bermuda seeking to restrain them from doing so on the ground that doing so was in breach of the Settlement agreement. In 2006, the liquidators wrote to Ting asserting that the Settlement Agreement was voidable on 56 [2010] UKPC 21, [2010] BLR 1718. Whether this is a true case of ‘lawful act of duress’ is contested: Rex Ahdar, ‘Contract doctrine, predictability and the nebulous exception’ [2014] CLJ 39, 46 (fn 47), citing authors such as McKendrick and Peel. 57 [2010] UKPC 21, [28]. 58 Borrelli [32]. 59 Lord Saville described what Mr Ting did as a ‘long process of evasion and prevarication’: Borrelli [27]. 60 For details of the agreement, see Borrelli [14]. 16 several grounds, including economic duress.61 The Board of the Privy Council agreed that the agreement was voidable for duress. Clearly focusing on the respondent’s conduct as well as his motive, the Board held that ‘opposing the scheme for no good reason’ was ‘unconscionable’.62 That decision was described as ‘high authority’, and a similar focus on the defendant’s conduct was relied upon, in Progress Bulk Carriers Limited v Tube City IMS LLC (the Cenk Kalpanoglu).63 In this instance (an appeal from arbitration), the court held that a settlement agreement was voidable for duress. The claimants, the disponent owner of the vessel ‘Cenk Kalpanoglu’, concluded a voyage charter on 2 April 2009 with the respondents to carry some shredded scrap from the USA to China. The charterer was shipping the cargo to fulfill its obligations under a sales contract. In breach of contract, the owner delivered the vessel to another charterer. The respondent did not accept the repudiation. Acknowledging the breach, the owner promised to find an alternative vessel and agreed that compensation for loss caused would be given. An alternative vessel (the Agia) was eventually found, but at such a date that a delay in shipment was inevitable. The respondent failed to negotiate a discount as a condition for accepting the late shipment, and on 27 April the owner made an offer of compensation, which was considerably less than the charterer’s loss 61 62 Borrelli [18-19]. Borrelli [35-32]. The Board’s disapproval of the respondent’s conduct was palpable, and it referred, several times, to the fact that Ting’s purpose in resisting the scheme, and his use of fraudulent methods to do so, were the source of the illegitimate pressure: see [8], [26], [28] and [32]. 63 [2012] EWHC 273 (Comm), [34] (Cooke J). 17 under the sales contract. In spite of the charterer’s protestation, on 28 April the owner reiterated their ‘take it or leave it’ final offer, which the charterer accepted under protest. The court confirmed the arbitrator’s finding that this amounted to duress. The court held that, although the behaviour of the owner was not bad faith, they ‘had manoeuvred the Charterers into the position they were in, … in order to drive a hard bargain’.64 Justice Cooke added that ‘their breach and subsequent misleading actions could validly be found to amount to illegitimate pressure’65. He then concluded that, as guidance, ‘the more serious the impropriety and the greater the moral obloquy which attaches to the conduct, the more likely the pressure is to be seen as illegitimate’.66 The position adopted is interesting since, in both cases, the court relied heavily on subjective matters such as malice, unconscionability, or lack of good faith in their assessment of the legitimacy of the pressure. Although the willingness of the courts to accept lawful threats as illegitimate in pure commercial cases has been praised,67 approval of the decisions is however far from unanimous. Criticisms are twofold. First, by focusing on the wrongdoer’s conduct and using subjective matters to define the legitimacy or otherwise of such conduct, the courts have been criticised for 64 The Cenk Kalpanoglu [40] (Cooke J). He added ([42)] that the behaviour of the owner ‘had to be seen both in the light of that prior repudiatory breach which was unlawful and the owner’s subsequent attempt to take advantage of the position created by that unlawfulness’. 65 The Cenk Kalpanoglu [43]. 66 The Cenk Kalpanoglu [43]. 67 Pey-Woan Lee, ‘Compromise and coercion’ [2012] LMCLQ 479, 479. 18 ‘making the test for lawful acts duress dependent on social morality’,68 which lacks a ‘conceptual basis’69 and allows too much judicial discretion70. Second, by focusing on such conduct, the courts are moving ‘from assessing the quality of the claimant’s consent to the nature of the defendant’s conduct’.71 In doing so, it is feared that ‘with doctrinal distortion, the relief may depend on being granted solely on the defendant’s unacceptable behaviour’.72 Although made in the context of the question of lawful acts of duress, such criticisms clearly apply to economic duress where the failure to define the limits of economic duress undermines the purpose of the doctrine. Borrelli and The Cenk Kalpanoglu were not the first case to rely on the conduct and motive of the wrongdoer to assert that the pressure was illegitimate. Indeed, in Kolmar Group AG v Traxpo Enterprises Pvt Ltd,73 to find that there was economic duress, Mr Justice Clarke held that the wrongdoer ‘cannot have thought that there was any legal or moral justification in the stance he was taking. He must have sensed Kolmar’s increasing desperation’.74 In reverse, the lack of ‘bad motive’ is also taken into consideration in order to decide 68 Ahdar (n 56) 47. 69 Carmine Conte, ‘The continued obscurity of duress’ (2014) LMCLQ 333, 339. 70 Ahdar (n 56) 47. 71 Conte (n 69) 336. 72 Conte (n 69) 339. 73 [2010] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 653. 74 [95]. The conduct of the contractor was equally important in the DSND Subsea case. 19 that the pressure is legitimate. For instance, in Patricia Wright v HSBC Ltd,75 where the claim for economic duress by the claimant was rejected, although Jack J accepted the vulnerability of Mrs Wright towards the bank, since she could not repay the money she owed without giving up her home, he nevertheless stated that the bank was entitled to that money76. Neither Borrelli nor The Cenk Kalpanoglu have helped to alleviate the considerable uncertainty this position brings. In fact, in Borrelli, although the Board emphasized the improper motive as well as the bad conduct of the wrongdoer, it nevertheless failed to clarify whether one of the two was enough or whether the two are cumulative.77 Furthermore, although the courts refer to good and bad faith in relation to the conduct of the wrongdoer, they only do so in very general terms. In Borrelli,78 the Privy Council made explicit reference to good faith and the necessity of ‘upholding justice’.79 The decisions have therefore not clarified whether bad faith is an essential element80 or whether good faith is always a good defence.81 For some, bad faith should not even be an ingredient of economic duress.82 75 [2006] EWHC 930 (QB). 76 Jack J added ([61]) that the bank ‘did not put any pressure on Mrs Wright to settle the Bank’s claim. She was not told that she must settle with the Bank if they were to continue lending. But in my view they would have been entitled to take that position’. For a similar position, see National Merchant Buying Society v Bellamy [2012] [EWHC] 2563 (Ch). 77 The difference is of crucial importance, for details, see Conte (n 69) 335. 78 [2010] UKPC 21, [2010] Bus LR 1718. 79 [32] and [33]. 80 Lee (n 67) 479. 20 This brings us to the second criticism. By concentrating solely on the conduct of the wrongdoer, the courts move away from the rationale of duress, which is the interaction of the illegitimacy of the pressure and the impairment of the victim following the pressure83. This links us to causation. The current causation requirement is very high. The justification is the perception that economic duress is not as serious as the other types84. Regardless of the justification85, the main problem is the lack of consistency in its application, something that both Borrelli and The Cenk Kalpanoglu fail to address. Although it is now accepted that the problem is not the absence of consent but an impaired one, the language of an ‘overborne will’ is not entirely 81 See Professor Chen-Wishart on cases such as Atlas v Kafco, The Alev, the Atlantic Baron etc, where, even though good faith was present, duress was nevertheless found: Chen-Wishart (n 6) para 8.4.4. 82 Nathan Tamblyn, ‘Causation and bad faith in economic duress’ [2011] J of Contract L 140. 83 Bigwood (n 51). 84 Huyton v Cremer [1999] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 620, 636 (Mance LJ). 85 Although the act itself may be less serious, it is nevertheless regarded as a wrong and there are nevertheless strong policy considerations to prevent it, even in commercial circles. Interestingly, cases sometimes argue economic duress as well as intimidation (even though the latter requirement is even more difficult to establish): for details, see Berezowsky v Abramovich [2011] EWCA Civ 153. This was the case in Cantor Index v Shortall [2002] All ER (D) 161 and in Kolmar Group AG v Traxpo Enterprises Ltd [2010] EWHC 1131, [2011] 1 All ER (Comm) 46. 21 gone.86 A difficult area in this respect is whether the victim had a practical alternative. Although the courts still consider it as a factor, there is some argument as to whether it really helps differentiate the cases where duress was found or not.87 In Borrelli, the Privy Council emphasized the lack of practical alternative. Yet, the court failed to clarify whether this is a separate requirement or simply a matter of evidence.88 In its emphasis on the lack of a practical alternative, the Privy Council in Borrelli stated that Ting had the victim ‘over a barrel’. This links us to the issue of the substance of the deal and whether fairness is a procedural issue or a substantive one. The matter is important especially in cases of renegotiation of contracts.89 Indeed, substantive concerns were important in Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd90 and Pao On v Lau Liu Long91 in deciding that there was no 86 Lord Hoffmann’s comments in R v AG for England and Wales [2003] UKPC 22 (see n 50), appear to show that the compulsion of the will theory is not completely abandoned. 87 Chen-Wishart (n 6) para 8.4.2. See also Hugh Beale et al, Chitty on Contracts (30th edn, Sweet and Maxwell 2008) para 7.003, where the authors write ‘it is submitted that a reasonable alternative is not an absolute requirement but rather strong evidence of whether the victim was in fact influenced by the threat.’ Conte goes further by stating that it should not even be taken into consideration since it is redolent of the overborne will theory. Conte (n 69). Dr Tamblyn however considers it as a crucial element: Nathan Tamblyn, Contract law in Hong Kong (Rights Press 2014) 151. 88 Conte (n 69). 89 J Beatson, ‘Use and abuse of Unjust Enrichment’ (Oxford, 1991), 95-136 90 [1991] 1 QB 1. 22 duress. This is, however, still a contentious issue, as is clear from Atlas v Kafco,92 which shows that correcting substantive unfairness alone cannot legitimize a threat to breach. Yet, substantive unfairness also appears to have played a role in The Cenk Kalpanoglu.93 In that case, in its assessment of the illegitimacy of the claim, the court took into consideration the impact of the settlement agreement on the defendant. The fact that the proposal for compensation was a $2 reduction per barrel compared to the loss of $8 per barrel was important in finding the pressure illegitimate. The substance therefore could not be discounted. If the terms are particularly disadvantageous to the ‘weaker side’, this will add weight to the claimant’s accusation of duress. For some, this highlights the similarity of duress with undue influence and unconscionable bargains, and the need to unify the doctrines to bring consistency.94 As undue influence is also a form of illegitimate pressure, there is a lot of common ground between them and merging them would therefore be possible. The more pertinent question however is whether this would solve the problems. 91 [1980] AC 614, 628. 92 [1989] QB 833 93 [2012] EWHC 273. 94 A particularly bad bargain will be used as evidentiary presumption for undue influence and such a particularly bad bargain will add weight to the accusation of unconscionability. As duress cuts across other categories of relief, Dr Capper questions what more duress offers as a doctrine: Capper (n 6) 172. See too Professor McKendrick, who argues that, as there is no clear concept of duress, it is difficult to identify its limits and therefore not clear whether duress plays the role that people say it does: McKendrick, (n10) para 17.2. 23 The future for defects of consent: unification? Following the objective theory of contracting, rules to protect consent have developed in a piecemeal manner. Although for some, the link of those rules to the doctrine of voluntariness is a sufficient measure for consistency,95 the reality nevertheless highlights a ‘patchwork of protection’.96 Two tentative proposals to this problem will be considered, unification of the vitiating factors, and, specifically, unification through legislation. Merging the doctrines Undue influence is an equitable doctrine, which has emerged alongside the common law of duress. The link between procedural and substantive unfairness is much stronger with undue influence, especially for presumed undue influence where substantive unfairness plays a strong evidentiary role97. The categories of relationship giving rise to presumed undue influence are reasonably wide: parent/child,98 95 Spark (n 2); Fabre Magnan and Sefton-Green (n 1) 408. 96 Capper (n 6). 97 The requirements can be inferred from a transaction at gross undervalue. If the transactional terms are particularly disadvantageous to the weaker side, this will help the presumption in favour of undue influence and will therefore add weight to the claimant’s accusation. 98 For a recent application, see Violett Hackett v (1) CPS (2) David Hackett [2011] EWHC 1170, where Silber J referred to the claimant, who had relied upon her son to manage her affairs, as ‘deaf, dumb, barely educated and illiterate’. 24 brother/sister, trustee/beneficiary, lawyer client, etc. Presumed undue influence is a particularly powerful tool and represents a difference with the US (where is no presumed undue influence). This is perhaps an area where the UK appears more protective than the US, especially in the light of the bias noted by Professor Harrison.99 The link between duress and (presumed) undue influence,100 as well as with capacity,101 would certainly allow for a merging of these vitiating factors. Yet, undue influence too suffers from conceptual problems102, so merging the two is therefore not ideal. Could unconscionable bargain be the answer? 99 See p 000 [Ref Harrison ch X]. 100 Macklin v Dowsett [2004] EWCA Civ 904, [2004] AllER (D) 95, Hammond v Osborn [2002] EWCACiv 885. In the latter, see especially Sir Martin Nourse at [32]. 101 The link between the two was mentioned in the first section of this chapter. For a more recent case, see Liddle v Cree [2011] EWHC 3294 (Ch), concerning the transfer of a farm to Liddle and Cree as beneficial joint tenants. The couple cohabited and farmed in partnership. After they separated, an agreement to divide the farm was reached in principle in 2009. Liddle however was bipolar, and his health significantly worsened in 2010. Solicitors were instructed to formalize the division of the property into two titles. As there was a difference in value between the two titles the issue of undue influence arose. The court held that, as the parties had separated, any trust and confidence had disappeared, and although the transaction was not wise for Liddle, it was not unfair in value, and therefore no duty arose on Cree’s part to advise Liddle to seek independent advice. 102 For a critique, see Mindy Chen-Wishart, ‘Undue influence: vindicating relationships of influence’ (2010) OJLS 231. 25 Unconscionability as a doctrine also arises out of equity. The link with contractual imbalance was clearly acknowledged in the Privy Council decision of Hart v O’Connor103 by Lord Brightman when he said ‘that the two concepts may overlap. Contractual imbalance may be so extreme as to raise a presumption of procedural unfairness such as undue influence or some other forms of victimization’.104 It is also present in cases such as Alec Lobb, where Millett LJ acknowledged that the severe substantive unfairness was important to establish that there was unconscionability.105 Given the limitation of capacity as a bargaining impairment, unconscionability has the advantage of affording protection to a wider array of people suffering from ‘bargaining disabilities’106 where it is clear that other special circumstances matter.107 103 [1985] AC 1000 (PC). 104 Hart 1018. 105 Lobb (Alec) Garages Ltd v Total Oil GB Ltd [1983] 1 WLR 87 where Millett LJ mentioned (94-5) that the undervalue, which had always been substantial was ‘in itself indicative of some presence of some fraud, undue influence or some other feature’. 106 The expression is borrowed from Chen-Wishart (n 6) para 9.4.3. The categories range from ‘poor and ignorant’ in Fry v Lane (1888) 40 Ch D 312 to the less educated in Cresswell v Potter [1978] 1 WLR 255. 107 See Backhouse v Backhouse [1978] 1 WLR 243, where a wife had signed a document without legal advice. In setting the agreement aside, the court remarked that, although the wife was an intelligent business woman with clear abilities, the break-up of the marriage was such that she found herself ‘in circumstances of great emotional strain’. Professor Chen-Wishart argues that the category of ‘poor and ignorant’ is outdated in a modern welfare state, Chen-Wishart, (n 6), para 9.4.3 at 26 The courts are however too careful here to couch their reasoning in language of procedural fairness.108 The contours of the doctrine are therefore equally fuzzy. A third solution often proposed is the adoption of a doctrine of unconscionability as it exists in the United States or in Australia. It is therefore very instructive to learn from Professor Harrison that the picture that unconscionability provides in the United States may not be of the panacea that many in the UK perceive the doctrine to be.109 As Professor Harrison suggests, statutory intervention may indeed be a better tool.110 Statutory intervention? Statutory intervention raises the difficulty of defining the criteria for having the contract set aside, which brings us back to the debate over the nature of defects of consent, one which appears to have reached a stalemate.111 This stalemate is perhaps due to the fact the parameters within which the debate takes place—the dichotomy of security of transactions and freedom of contract—is too simplistic and a little too 354. Unfortunately, given the rising level of indebtedness and illiteracy, I am not entirely sure I agree with such a statement. 108 Thomas therefore says that we are talking of ‘unconscionably-obtained bargains rather than unconscionable bargains’: Charlotte Thomas, ‘What role should substantive fairness have in the English law of contract? An overview of the law’ (2010) Cambridge Student LR, 177, 186. 109 See p 000 of this book [Ref Harrisson, ch, part IV D]. 110 See p 000 of this book [Ref Harrisson, part IV, B]. 111 Chen-Wishart (n 102) 232. 27 constrained. Indeed, we are far away from nineteenth century conception of freedom of contract based on the idea that all parties are equal. Parties are clearly not all equal. The matter must also be considered in the light of the specialization of contracts, primarily through secondary legislation.112 By widening the debate, and considering the fields of consumer and competition law, a tentative proposal can be made. In consumer law, the Directive on unfair commercial practices113 is of particular relevance. Although the Directive excludes vitiating factors from its remit (recital 9), unfair commercial practices nevertheless have a lot in common with duress (and fraud/misrepresentation).114 Indeed, there are two categories of unfair commercial practices, one linked to the behaviour of the wrongdoer and another linked to the impact of that behaviour. The directive recognises as unfair, practices that are very similar to duress (and misrepresentation). Moreover, the conditions are also similar to duress, since there must be a wrong (contrary to professional diligence, as specified in article 5(2)(a)) and the wrong must have been a determining factor in the consumer’s decision (article 9c). Finally, it appears that other vitiating factors are also included.115 112 It is not clear whether the remedies for defects of consent can be added to those available under the Council Directive (EC) 99/44 on consumer sales, [1999] OJ L 171/12. Fabre-Magnan and Sefton Green (n 1) 407. 113 See n 7 above. 114 Carole Aubert de Vincelles, ‘Le code de la consommation à l’épreuve de nouvelles notions’ in Carole Aubert de Vincelles and Natacha Sauphanor-Brouillaud, Les 20 ans du code de la consommation: Nouveaux enjeux (LDGD 2013) 25. 115 Art 9 clearly stipulates ‘use of harassment, coercion and undue influence’: Aubert de Vincelles (n 114) 25. 28 While the Directive could therefore be used as a template for statutory intervention, the text is far from perfect. Although the text brings together several areas (consumer law, competition law, protection of the weaker party, and protection of the market), the interaction between them is not clearly defined and, as a result, it is neither completely protective of the consumers nor of the market.116 Competition law is also interesting, since duress and competition law are linked by their concern for the use and abuse of power and pressure.117 The notion of dominance (or lack of it) is therefore particularly important here.118 Yet, as the two 116 Aubert de Vincelles (n 114) 29. 117 Pinar Akman, ‘The relationship between economic duress and abuse of a dominant position’ [2014] LMCLQ 100, 100. An interesting parallel is the French system, which links competition and unfair practices with the notion of dépendence économique (economic dependency): art L 442-6-2, French Commercial Code. 118 In The Cenk Kalpanoglu, the fact that the charterer used the breach for their own advantage was a clear factor for the court in finding their behavior illegitimate, a point noted by Lee (n 67) 479. The issue of dominance also appears important for Burrows in his assessment of good faith/bad faith of the wrongdoer, who states that, if the threatened breach is used to exploit a claimant’s weakness rather than solving a problem for the defendant, this is bad faith: Andrew Burrows, The Law of Restitution, (3rd edn, OUP 2010) 233. A slightly different test is proposed by Chen-Wishart, who advocates that it should be illegitimate for a party to threaten breach if he can perform without modification, but it should be legitimate for a party to renegotiate to his advantage if he has no practicable alternative but to do so to perform the contract: Chen-Wishart (n 6) para 8.4.4. 29 areas serve different functions, the differences as well as the similarities must be clearly understood in order to see where the intersection clearly lies and where the similarities could help the two disciplines.119 Although recent developments have highlighted the increasing recognition of the need for closer interaction between competition and consumer law,120 how precisely those fields interact has yet to be defined. Conclusion The aim of this paper was to consider critically the relation between defects of consent and unfairness. Although they are undoubtedly linked, the whole area nevertheless lacks consistency. In comparison, the US position, although not perfect, appears more coherent, thanks, it seems, to the presence of unconscionability. Yet, as unconscionability (or a merging of the various defects of consent considered in this chapter) is unlikely to be adopted in the UK, a different solution must be found. In the light of an increasing specialization of contracts, and a growing relationship between fields traditionally seen as separate (competition and consumer laws), defects of consent cannot be seen in a vacuum. Understanding the function and purpose of defects of contract within as well as outside the discipline is crucial. It therefore seems 119 See Akman (n 117) 120-126. 120 See the remit of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (n 7), as well as the Consumer Rights Bill currently under consideration by the UK Parliament (which proposes to use tools such as mediation and other alternative methods of dispute resolution in relation to consumers). 30 crucial to explore further the interaction between defects of consent, competition, and consumer law. Only by doing so can one perhaps helps to build clearer foundations. 31