Political Socialization Patterns in Younger and Older American

advertisement

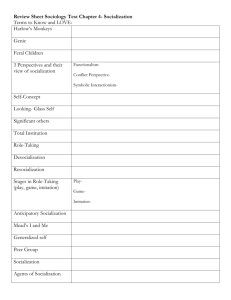

Political Socialization Patterns 1 Political Socialization Patterns in Younger and Older American Adolescents Abstract Through a survey of more than 1,200 pairs of teenagers and their parents, this study examined what factors lead to political knowledge and political participation in young children. We also examined whether these factors changed as children aged. Tweens (12-14 years old) seemed to rely more on parental political involvement and family political discussion for their political knowledge, while teens (15-18) relied more on finding knowledge through school and the media. In diagramming how knowledge moved to participation however, political efficacy or the belief that their actions made a difference were the largest predictors for tweens and teens. The study suggests that programs designed to get children interested and participating in politics should focus on developing self-efficacy instead of simply imparting knowledge or political opinions. Political Socialization Patterns 2 Introduction In the 2008 presidential election, an estimated 23 million 18- to 29-year-olds voted, representing the second-largest turnout of youth voters in American history (Willis, 2009). More than 65 percent, in fact, voted for President Obama. But it is unlikely and problematic to ascribe the record numbers of young votes exclusively on the charismatic candidate seeking to make history. In fact, political socialization, the process that leads young people to learn about, think about and participate in a democracy, probably began long before any of them were eligible to vote. The goal of this study is to explore when political socialization begins and whether the causal processes that drive it change over time. Using a study of more than 1,200 children/parent pairs who filled out a mail survey in the spring of 2008, about six months before the election, we examine what factors lead children ages 12-18 to participate politically, either online or off, and how their age affects the process. We define political socialization is a network of responses in cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. We focus on the differential impact of structural, demographic, and cognitive variables on this network of responses while creating two groups of young respondents: “tweens” (aged 12-14) and “teens” (aged 15-17). Literature Review Adolescent development of political self: Influence of family, school and news media Eveland, McLeod and Horowitz (1998) found age to be a significant predictor for political knowledge. As children got older, the influence of news media exposure on political knowledge was greater for older children rather than younger. News media, however, are just Political Socialization Patterns 3 one factor in political knowledge acquisition. Other developmental aspects of adolescence need to be examined if we wish to understand the process of political socialization. Foremost among these are political identity development and a sense of political efficacy. Early studies in political socialization assumed the political system or society and its socialization agents were relatively effective in transmitting certain basic political values or information, and that the individual absorbed these without much personal interpretation (Torney-Purta, 1995; Easton & Dennis, 1969; Greenstein, 1965; Jennings & Niemi, 1968). These studies failed to consider the fact that adolescents go through a phase where they critically question what parents and school teach. Adolescents themselves can play an active role in their political identity formation once motivated to follow news and participate in conversations, Kiousis, McDevitt, & Wu (2005) found, thereby refuting the transmission model of political socialization. Jennings and Niemi (1974) also found the parent-adolescent correlation in terms of political opinion was low, indicating parents’ political views did not necessarily transmit to their teenagers. Erikson’s (1966) theory of development states that an identity search begins in early adolescence, and internal and external experiences during childhood and adolescence are lead to a commitment to a particular values and beliefs. Many adolescents go through the stage of searching for their identity and will question parents’ instructions and seek autonomous decisions. Marcia (1980) said adolescents identity formation relies on whether they have explored various alternatives and made firm commitments to an occupation, a religious ideology or political values. Adolescents’ effort to influence parents, and to outright provoke them in some cases, can cause a shift in the structure of family communication, reflecting the child’s desire for autonomy (McDevitt, 2005). Also, identity search leads to more emphasis on peers. McDevitt and Kiousis (2007) found that in terms of political activism, family and school acted as socialization agents Political Socialization Patterns 4 promoting compliant voting, while peer group discussion fostered political activism. Such results suggest political socialization is not necessarily a process of inculcation and enculturation controlled by the adults. Once we acknowledge the autonomy seeking of adolescence done through peer interaction, self-identification with unconventional citizenship and activism can be promoted. In addition, early political socialization literature did not address the possibility that the political voices of adolescents may influence the parents. McDevitt and Chaffee (2002) defined this as “trickle-up politicization,” and found there are ample possibilities for adolescents to not merely follow the parents political identification and political behavioral patterns. Socialization, or re-socialization of the parents is also possible. The environment that makes this ‘trickle-up’ influence possible is school. In school, adolescents are exposed to political values and ideas that may be different from what they grew up with in their family or from their peers. Schools potentially provide social interaction that represents a level of political stimulation and communication that may not be available from parents at home (Kiousis & McDavitt, 2008). School intervention, such as the Kids Voting USA, was found to not only encourage adolescents to be politically interested and knowledgeable, but also it helped lead them to a more motivated discussion in school (McDevitt, 2005; McDevitt & Chaffee, 2002). Thus, it is possible to expect that even for a politically active teenager who follows his parents’ political actions and party identification, school will provide the public sphere where he can hear about different arguments. Exposure to political diversity, which may not be available within a family environment, can also act as a motivator for teenagers to act differently from their parents. Younger teens or tweens are likely to still be in the stage of asking questions about political values, or even be at the foreclosure stage, which Marcia (1980) defines as being Political Socialization Patterns 5 committed to some identity without going through the crisis of deciding what really suits them best. In addition, they may also feel politics is removed from their everyday lives. By late adolescence, many young men and women achieve a sense of identity (Shaffer, 2009). Not only will older adolescents feel more of a need to affiliate, commit and feel responsible to politics (Sherrod, Flanagan, & Youniss, 2002), but they will also have had ample time to go through all the possible options in their search for a political identity. They may reach a stage where they personally commit to the values. In fact, family communication patterns were no longer related to older adolescents’ level of political interest, or political knowledge (Meadowcroft, 1986), implying that once children gain adequate skills, they are able to internalize, comprehend fully and act in ways of their own. If anyone in this age group shows identical political perspective with their parents, they have most likely chosen to follow their parents’ point of view, instead of merely doing what they have been told. The news media play a crucial role for adolescents who actively ask questions about their political values and identities. Media helps adolescents start to seek autonomy and independence from their parents and look for sources outside of family. Adoni (1979) argued mass media serve as socializing agents by providing a direct link to the content adolescents need to develop political values and contribute to the social contexts where they can exercise value orientations. Now, the Internet provides a direct outlet that can be used whenever there is a need for information, and it has been found to be the most often used political news outlet for adolescents (Gross, 2004). As the capacity to think about political matters begins in adolescence (Eveland, McLeod, & Horowitz, 1999), young people start to mentally process the abstract ideas and concepts that serve as the bases for politics. As the adolescents’ cognitive ability allows them to elaborate on the news and feel efficacious about their political opinion, they will go through the process of not only discovering what they believe in terms of politics but also understand what others’ Political Socialization Patterns 6 perspectives are. Initially, the family communication and parental participation will guide the adolescents to be exposed and build interest in political behavior and later school curricula such as the Kids Voting program, and the news that they decide to follow can equip the adolescents to make political decisions which reflect their own attitudes (Meirick & Wackman, 2004). In sum, the first two research hypothesis can be stated as followed: H1: For teens, school education and news media use will be significant predictors of political knowledge, traditional political participation, and online political participation, while family communication and parental political participation will not. H2: For tweens, family communication and parental political participation will be significant predictors of political knowledge, traditional political participation, and online political behavior, while school and news media use will not. Development of political efficacy Another important psychological aspect of political socialization is the development of political efficacy. Political efficacy is conceptually defined as “the feeling that political and social change is possible, and that individual citizen can play a part in bringing about the change (Campbell, Gurin, & Miller, 1954).” Political efficacy is recognized to contain two separate components: internal efficacy referring to beliefs about one’s own competence to understand and to participate effectively in politics, and external efficacy which refers to beliefs about the responsiveness of governmental authorities and institutions to citizen demands (Kenski & Stroud, 2006). Many studies have tried to find the antecedents of increasing political efficacy. Focus group interviews by Wells and Dudash (2007) suggested many young voters do not feel they have enough knowledge to participate, thereby establishing a connection between political knowledge and political efficacy. Gniewosz, Noack, and Buhl (2009) found that supporting and transparent parent-child interactions, and an open, transparent and positive classroom climate Political Socialization Patterns 7 1 was negatively related to adolescents’ political alienation. The type of news media adolescents used also influenced their level of political efficacy. Late-night TV shows (Hoffman & Thompson, 2009), campaign messages, political advertising, and debates (Kaid, McKinney, & Tedesco, 2007) directly targeted to young voters (McKinney & Banwart, 2005) increased adolescents’ and college students’ political efficacy. Political efficacy is also an important predictor of adolescents’ current and future political participation. Hoffman and Thompson (2009) found political efficacy significantly mediated the effects of late-night TV viewing on civic participation, such as joining student government, debate club, and similar youth organizations or volunteering for any neighborhood or civic group. Vecchione and Caprara (2009) argued efficacy predicted engagement in political manifestations, donation to the political associations, contacting politicians or working for a political party. Similarly, the Rock the Vote campaign on MTV increased college students’ intention to vote (McKinney & Banwart, 2005). While civic and political participation as a teenage is not the same as voting as an adult, these behaviors in early adolescence not only predicted participation in late adolescence, but also the level of civic engagement in young adulthood, after they reached the age to vote (Zaff, Malanchuk, & Eccles, 2008). On the other hand, political cynicism reflects low external efficacy (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006; Hoffman & Thompson, 2009). Cynicism and decreased external political efficacy has been found to detract from current and future political activities, especially for adolescents (Kaid, et al., 2007; Rodgers, 1974). Studying what could influence the political efficacy and cynicism of black children, Rodgers (1974) found increased political knowledge correlated positively with political cynicism and decreased political efficacy. Bandura (2006) said people who generally believe they can achieve desired changes through their collective voice and view Political alienation is defined as citizens’ subjective feelings about their abilities to affect the political system’s performance at the individual level. Four dimensions political alienation was defined to be (a) political powerlessness, (b) political meaninglessness, (c) political normlessness, and (d) political isolation (See Gniewosz, et al., 2009) 1 Political Socialization Patterns 8 their governmental system as trustworthy tend to participate actively in conventional political activities, whereas the apathetic are more likely to be disaffected. While Rodgers’ study did not examine whether these African American adolescents showed high voting rates in the future, he did try to explain the lower political participation rate of young African Americans through their low political efficacy and high political cynicism. Studies examining the role of political efficacy in terms of political socialization have not answered the question asking ‘when’ efficacy about one’s role in politics starts to develop. That is one of the main research question this study examines. It can be inferred from the studies linking political knowledge and political efficacy that teens who have a better understanding of and enough information about politics would feel more efficacious compared to tweens. However, based on the political cynicism research, it is also possible that teens have learned that the political activities they participate or the future votes they cast might not make much difference, resulting in increased political cynicism and leading them to feel less efficacious. Some studies do show that the naïve belief and admiration towards politicians that was found to be high in early elementary school years diminished by the time children went to middle school (Easton & Dennis, 1969; Greenstein, 1965). Because of the mixed results on the age difference in political efficacy, we propose the following hypotheses. H3: Political efficacy will be a stronger predictor of political participation, both online and off, for teens than tweens. On the other hand, it can be inferred from the literature that the level of political efficacy that teens or tweens feel will mediate the relationship between education from socialization agents and their participation in political activities. H4: Political efficacy will mediate the influence of family communication, parental political participation and school education on political socialization (traditional participation, and online political participation). Methods Political Socialization Patterns 9 The authors obtained a nationwide sample of teenagers and their parents between May 20 and June 25, 2008 using Synovate, a commercial survey research firm. Synovate employs a stratified quota sampling technique to recruit respondents. Initially, the company acquires contact information for millions of Americans from commercial list brokers, who gather identifying information from drivers’ license bureaus, telephone directories, and other centralized sources. Large subsets of these people are contacted via mail and asked to indicate whether they are willing to participate in periodic surveys. Small incentives are offered, such as pre-paid phone cards, for participation. Rates of agreement vary widely across demographic categories. For example, five to ten percent of middle class recruits typically consent, compared to less than one percent of urban minorities. It is from this pre-recruited group of roughly 500,000 people that demographically balanced samples are constructed for collection. To achieve a representative pool of respondents, Synovate created a stratified sample that reflected the properties of the population within each of nine census divisions in terms of household income, population density, age, and household size. This starting sample is then adjusted within a range of subcategories that include race, gender, and marital status in order to compensate for expected differences in return rates (see Shah, Cho, Eveland & Kwak, 2005; Shah et al., 2007 for details). For the purposes of this study, this technique was used to generate a sample of households with children age 12-17. A parent in the selected households was contacted via mail, asked to complete an introductory portion of they survey and then to pass the survey to the 12-17 year old child in the household who most recently celebrated a birthday. This child answered a majority of the survey content and then returned the survey to the parents to complete and return. This sampling method was used to generate the initial sample of 4,000 respondents for the 2002 Life Style Study. Of the 4,000 mail surveys distributed, 1,325 responses were received, which represents a response rate of 33.1 percent against the mailout. A small number of these responses Political Socialization Patterns 10 were omitted to do incomplete or inconsistent information, resulting in a slightly smaller final sample. In all, the study examines 1,291 teens between the ages of 12 and 17. We divided respondents into two age groups: tween, with 614 participants, and teens, with 617. To begin, we used confirmatory factor analysis to create scales to measure independent and dependent variables. We measured political knowledge with three questions that asked participants the following political questions: Which political party is more conservative? Which political party controls the House of Representatives? Which political party did Ronald Reagan belong to when he was president? A correct answer was scored 1, while incorrect responses were 0. On a scale of 0-3, tweens had a mean score of less than 1, while teens’ mean was 1.11. We measured efficacy with two questions that asked how influential the respondents thought they were among their friends and how often their friends sought their opinions. The questions had a statistically significant correlation at the p<.01 level. Online political participation combined questions about how often the young participants used the following Internet features to discuss politics: social networking sites, news Web sites, political blogs, e-mail, text messages and online videos (Cronbach’s =.860). Offline political participation was an aggregation of questions about how frequently they did volunteer work, contributed money to a campaign, attended rallies or speeches, worked for candidates or displayed a candidate’s button or sticker (Cronbach’s =.818). Results The main question this study asked was what difference exists, if any, between tweens, or those 12-14, and teens, those 15-17, in the political socialization process. To begin to answer this, our analysis began with an independent samples t test to identify possible differences between tweens and teens (See Table 1). Statistically significant mean differences existed in four areas: Internet news use, learning about politics in school, political knowledge and online political Political Socialization Patterns 11 participation. In all four, teens were more likely to participate in those areas than tweens. Teens in the study used the Internet more for news and said they learned more about politics in school than tweens, which supported H1.They also had significantly greater political knowledge and much higher online political participation. Tweens also scored lower on parental political involvement and family talk, but neither of these differences was statistically significant. This could suggest that H2: Tweens’ knowledge and participation would be predicted more by family communication and parental political involvement. However, the t tests do not predict any of the dependent variables in the study. To do that, we set up linear regressions for tweens and teens separately to see which of the demographic, school and family communication variables would predict our three socialization measures. For knowledge (see Table 2), the most significant predictors for tweens and teens were income (=.1, .144, p<.01), parent’s education (=.16, .18, p<.01), and talking about politics with the family (=.21, .2, p<.01). This suggests partial support for H2, but not for H1. The literature suggests family talk would be a significant predictor for tweens and not necessarily for teens. It also suggests teens’ political discussion at school and media use would also significantly predict their knowledge. When looking at online political participation (see Table 3), we found partial support for H2 and H1. Newspaper use (=.14, p<.01), Internet news use (=.1, , p<.05), and family talk (=.12, p<.01) were all significant predictor for tweens, along with learning about politics in school (=.2, p<.01), which was contrary to what we supposed in H1. For teens, learning about politics in school was the most significant predictor (=.23, p<.01), which supported H1, but family talk was also statistically significant at the p<.01 level with a =.17. The pattern of partial support for H1 and H2 continued when examining offline political participation (see Table 4). Tween participation was predicted most strongly by parental political Political Socialization Patterns 12 involvement (=.436, p<.01), which supported H2. But learning about politics in school (=.25), was also significant at the p<.01 level along with Internet news use (=.11), which did not support the hypothesis. For teens TV news use (=.1), Internet news use (=.15), and learning about politics in school (=.22) were significant predictors at the p<.01 level, which supported H1. But parent political involvement was the most significant predictor at =.4, p<.01. These regressions suggest that another mediating variable may better explain the differences in political involvement between tweens and teens. We added our efficacy measure to the regressions to test H3: Efficacy will predict participation more for teens than tweens. In two regressions of online and offline participation we found only partial support for this hypothesis. For both tweens and teens efficacy was a statistically significant predictor of online (=.16, .12, p<.01) participation (see Table 6) and offline (=.11, .15, p<.01) participation (see Table 7). The strongest predictor for tweens and teens of online use was Internet news use (=.24, .30, p<.01), and for offline it was parental political involvement (=.43, .4, p<.01). To understand why, we predicted efficacy for tweens and teens (see Table 5) and found that tweens relied on newspaper use (=.14, p<.01), family talk (=.12, p<.01) and learning about politics in school (=.2, p<.01), while teens relied only on family talk (=.17, p<.01) and learning about politics in school (=.23, p<.01) to predict efficacy. This suggested that adding efficacy to the model changes the dynamic of the other variables. To test H4: whether efficacy mediates the political socialization process for tweens and tweens, we added set up path analysis models in Amos, a structural equation modeling software package from SPSS, placing knowledge and efficacy between parental influence, school and family discussion. We adjusted the models for the best fit (see Figures 1 and 2) and found that for both tweens and teens, efficacy had the largest standardized regression weight (=.32, .26, p<.01). The Chi square divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN) statistic was 32.905 for tweens Political Socialization Patterns 13 and 26.887 for teens. Although high, both were less than the CMIN for the independence model, which accounts for all paths equally. The RMSEA statistic was .230 for tweens and .207 for teens, which was also high, but both numbers were once again less than the independence model and suggested a good fit. The path models suggested a political socialization pattern toward offline or real world participation, such as campaigning for a candidate or donating money. Parent’s political involvement, family political talk and learning about politics in school were highly correlated and seemed to work together to predict a child’s political knowledge. Knowledge by itself did not predict participation. The path between knowledge and participation was not significant in either model. Knowledge and learning about politics in school, however, worked together to predict efficacy, which was the greatest predictors of offline participation. Discussion The goal of this study was to test a model that accounts for many of the factors leading to political socialization. As the literature suggests, there is no single issue that will lead youth to become politically active, especially before they can even vote. A discussion of socialization needs to include demographic, media, school, and psychological variables. It also cannot discount the importance of a child’s age. The maturation process affects how much young people learn and trust the sources of their knowledge. It also impacts how successful they think they will be in applying their political knowledge. First, our study suggests that age helps determine how children learn about politics and what media sources they will choose. Teens, or those 15-17, are more likely to turn to the media for information about politics, as the literature suggests, because they are trying to find their own way in the world. They are also more likely to use the Internet to participate politically, our study Political Socialization Patterns 14 suggests. Younger children or tweens will rely more on family, especially as they try to learn about the political process. As children apply their knowledge, the influence of family and even school is not enough. They have to believe their actions will make a difference, that they or the candidates they choose to support will be successful. Political self-efficacy mediates the effect that parents, school, and even the media can have on whether they participate. Efficacy, in fact, is such a strong mediating variable that it might determine the political socialization process. Translating knowledge to action requires this belief which is a product of school, family, and media. We believe efficacy is the reason we found only partial support for many of the hypotheses the literature suggested. The path models suggested that teens and tweens follow a similar path to action. Almost everyone starts by following in the parents’ political footsteps. This can lead to talking as a family about politics and can inform political discussions at school. All three work together to inculcate in tweens and teens the desire to gain political knowledge. But simply learning facts and talking about politics at school and at home is not enough. That knowledge must lead tweens and teens to believe in the system and to think they can make a difference. Strong political education programs, such as Kids Voting USA, helped instill this belief in young people. This study suggests it is important for political education in schools and at home to revolve around self-efficacy if the goal is to create children who will get actively involved. Even online, where participation is as easy as clicking a button or adding something to a Facebook page, self-efficacy determines a person’s likelhood to act. The models tested in this study do not account for all of the variables that lead to selfefficacy. The low fit statistics suggest that other factors are at play. The models also do not account for demographics, such as income, which the regressions suggest are significant. Further studies should adjust the model to determine what other factors influence knowledge and Political Socialization Patterns 15 efficacy formation. These factors could include previous experience or success and the impact of other models, such as peers or people in the media. However, we think the significant path between efficacy and participation and the large adjusted R2 scores of the regression equations suggest that efficacy plays an important role in political socialization. Schools and parents could help young people to get interested and participate in building their nations if they focus their efforts on helping them believe they can make a difference. This belief might be just enough, and in that case, age does not matter. Political Socialization Patterns 16 References Adoni, H. (1979). The functions of mass media in the political socialization of adolescents. Communication Research, 6(1), 84-106. Bandura, A. (2006). Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In F. Pajares & T. C. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents: Information Age Publishing. Campbell, A., Gurin, G., & Miller, W. E. (1954). The voter decides. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. Easton, D., & Dennis, J. (1969). Children in the political system. New York: McGraw-Hill. Eveland Jr, W. P., & McLeod, J. M. (1998). Communication and age in childhood political socialization: An interactive model of political development. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 699-718. Gniewosz, B., Noack, P., & Buhl, M. (2009). Political alienation in adolescence: Associations with parental role models, parenting styles and classroom climate. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(4), 337-346. Greenstein, F. I. (1965). Children and politics. New Haven: Yale University Press. Gross, E. F. (2004). Adolescent Internet use: What we expect, what teens report. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6), 633-649. Haas, C. (2008). The Obama campaign- Social media. Retrieved December 10th, 2009 from http://www.barackobama.com. Hoffman, L. H., & Thompson, T. L. (2009). The effect of television viewing on adolescents' civic participation: Political efficacy as a mediating mechanism. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 53(1), 3-21. Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1968). The transmission of political values from parent to child. The American Political Science Review, 62(1), 169-184. Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1974). Political character of adolescence: The influence of families and schools. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kaid, L. L., McKinney, M., S., & Tedesco, J., C. (2007). Introduction: Political information efficacy and young voters. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(9), 1093-1111. Kenski, K., & Stroud, N. J. (2006). Connections Between Internet Use and Political Efficacy, Knowledge, and Participation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50(2), 173 192. Kiousis, S., McDevitt, M., & Wu, X. (2005). The genesis of civic qwareness: Agenda setting in political socialization. Journal of Communication, 55(4), 756-774. Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley. Political Socialization Patterns 17 McDevitt, M. (2005). The partisan child: developmental provocation as a model of political socialization. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(1), 67-88. McDevitt, M., & Chaffee, S. (2002). From top-down to trickle-up influence: revisiting assumptions about the family in political socialization. Political Communication, 19, 281-301. McDevitt, M., & Kiousis, S. (2007). The red and blue of adolescence: Origins of the compliant voter and the defiant activist. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(9), 1214-1230. McKinney, M., S., & Banwart, M. C. (2005). Rocking the youth vote through debate: Examining the effects of a citizen versus journalist controlled debate on civic engagement. Journalism Studies, 6(2), 153-163. Meadowcroft, J. M. (1986). Family communication patterns and political development. Communication Research, 13(4), 603-624. Meirick, P. C., & Wackman, D. B. (2004). Kids Voting and political knowledge: Narrowing gaps, informing votes. Social Science Quarterly (Blackwell Publishing Limited), 85(5), 11611177. Rodgers, H. R., Jr. (1974). Toward explanation of the political efficacy and political cynicism of black adolescents: An exploratory study. American Journal of Political Science, 18(2), 257-282. Shaffer, D. R. (2009). Social and personality development (9th ed.). Wadsworth: Cengage Learning. Sherrod, L. R., Flanagan, C., & Youniss, J. (2002). Dimensions of citizenship and opportunities for youth development: The what, why, when, where, and who of citizenship development. Applied Developmental Science, 6(4), 264–272. Torney-Purta, J. (1995). Psychological theory as a basis for political socialization research. Perspectives on Political Science, 24(1), 23. Vecchione, M., & Caprara, G. V. (2009). Personality determinants of political participation: The contribution of traits and self-efficacy beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 487-492. Wells, S. D., & Dudash, E. A. (2007). Wha'd'ya know?: Examining young voters' political information and efficacy in the 2004 election. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(9), 1280-1289. Zaff, J. F., Malanchuk, O., & Eccles, J. S. (2008). Predicting positive citizenship from adolescence to young adulthood: The effects of a civic context. Applied Development Science, 12(1), 38-53. Political Socialization Patterns 18 Political Socialization Patterns 19 Tables Table 1 Independent samples T-test between tweens (12-14) and teens (15-18) on perceived news bias, political knowledge, online political participation, and offline political participation. Tween N Household Size Teen Mean 614 4.1547 N 617 (1.26588) Income 614 45.5163 613 2.8858 617 611 1.486 615 608 2.1069 616 610 .7852 614 611 3.4239 615 614 5.0627 611 611 3.3307 617 614 .8893 615 613 2.6436 617 609 1.4828 614 609 1.8440 1.565 .833 1225 2.5277 2.621 1220 1.0439 2.336** 1223 3.4464 .220 1220 5.1783 1.124 1229 3.6697 3.157** 1224 1.1135 3.918** 1229 2.7695 2.374 1225 3.300** 1221 1.218 1221 (.94475) 614 (.90327) Offline Political Participation 1226 (1.05533) (.91365) Online Political Participation .092 (1.94501) (.94934) Political Efficacy 2.8911 (1.82666) (1.81179) Political knowledge scale 1229 (1.79454) (1.78097) Learned about politics in school 2.283 (2.05059) (1.77325) Family Talk 46.2934 (2.82988) (1.81621) Parental Polical Involvement 1229 (1.7102) (2.78146) Internet news use -1.414 (.98374) (1.6309) Newspaper use df (5.91222) (1.01621) TV News use (local and network) 4.0535 t (1.24658) (6.03083) Parent's mean education Mean 1.6661 (1.03492) 614 (1.01646) Note: * = p < .05, *** = p < .01. Standard Deviations appear in parentheses below means. 1.9153 (1.03100) Political Socialization Patterns 20 Table 2 Linear regression analysis predicting knowledge for tweens (12-14) and teens (15-17). (N = 1,291) Variable Tweens SE(B) B β Teens SE(B) B β Household Size .006 .029 .007 -.002 .033 -.002 Income .016 .007 .100* .026 .008 .144** Parent's mean .149 .041 .160** .195 .046 .182** -.004 .025 -.008 .003 .025 .005 Newspaper use .018 .015 .052 -3.405E-5 .015 .000 Internet news .004 .022 .007 .021 .021 .042 -.013 .022 -.025 -.021 .025 -.035 Family Talk .112 .023 .209** .114 .027 .196** Learned about .067 .023 .128 .039 .024 .071 education TV News use (local and network) use Parental Polical Involvement politics in school R2 Adjusted R2 .154 .141 .165 .152 Note: *=p<.05, **= p < .01. Table 3 Linear regression analysis predicting online political participation for tweens (1214) and teens (15-17). (N = 1,291) Variable Household Size Tweens SE(B) B β Teens SE(B) B β -.008 .026 -.011 .025 .030 .030 .004 .006 .026 -.004 .007 -.025 -.032 .036 -.036 -.024 .043 -.023 .048 .021 .085* .051 .023 .083* Newspaper use .025 .013 .077* -.013 .014 -.035 Internet news .131 .020 .252** .144 .020 .286** .082 .019 .160** .095 .023 .164** Family Talk .034 .020 .067 .058 .024 .102* Learned about .115 .020 .229** .092 .022 .172** Income Parent's mean education TV News use (local and network) use Parental Polical Involvement politics in school R2 Adjusted R2 Note: *=p<.05, **= p < .01. ..296 .285 .260 .249 Political Socialization Patterns 21 Table 4 Linear regression analysis predicting offline political participation for tweens (12-14) and teens (15-17). (N = 1,291) Variable Tweens SE(B) B β Teens SE(B) B β Household Size .019 .027 .024 .031 .028 .037 Income .001 .006 .006 .007 .007 .039 -.060 .037 -.060 -.061 .041 -.058 .057 .022 .090* .059 .022 .097** Newspaper use .026 .014 .070 .009 .013 .026 Internet news .067 .021 .116** .075 .019 .149** .250 .020 .436** .231 .022 .399** Family Talk .005 .021 .008 -.022 .023 -.039 Learned about .142 .021 .252** .116 .021 .218** Parent's mean education TV News use (local and network) use Parental Polical Involvement politics in school R2 Adjusted R2 .398 .389 .328 .318 Note: *=p<.05, **= p < .01. Table 5 Linear regression analysis predicting political efficacy for tweens (12-14) and teens (15-17). (N = 1,291) Variable Tweens SE(B) B β Teens SE(B) B β Household Size -.008 .028 -.011 .000 .030 -.001 Income -.001 .007 -.009 -.009 .007 -.055 Parent's mean -.045 .039 -.050 .022 .043 .023 .002 .023 .003 -.013 .023 -.024 Newspaper use .046 .014 .140** .007 .014 .020 Internet news .053 .021 .105* .015 .020 .032 .046 .021 .090* -.025 .023 -.047 Family Talk .063 .022 .121** .090 .024 .174** Learned about .102 .022 .202** .112 .022 .231** education TV News use (local and network) use Parental Polical Involvement politics in school R2 Adjusted R2 Note: *=p<.05, **= p < .01. .182 .170 .116 .103 Political Socialization Patterns 22 Table 6 Linear regression analysis predicting online political participation for tweens (12-14) and teens (15-17) while adding efficacy to the model (N = 1,291) Variable Household Size Tweens SE(B) B β Teens SE(B) B β -.007 .025 -.010 .015 .029 .018 .004 .006 .027 -.004 .007 -.021 -.026 .036 -.029 -.025 .042 -.024 .048 .021 .085* .046 .023 .076* Newspaper use .018 .013 .055 -.018 .014 -.051 Internet news .123 .020 .235** .151 .019 .301** .074 .019 .145** .100 .023 .173** Family Talk .025 .020 .048 .046 .024 .081 Learned about .099 .020 .198** .077 .022 .146** .037 .156** .132 .040 .121** Income Parent's mean education TV News use (local and network) use Parental Polical Involvement politics in school Efficacy R2 Adjusted R2 .155 Note: *=p<.05, **= p < .01. .316 .304 .281 .269 Political Socialization Patterns 23 Table 7 Linear regression analysis predicting offline political participation for tweens (12-14) and teens (15-17) while adding efficacy to the model (N = 1,291) Variable Tweens SE(B) B β Teens SE(B) B β Household Size .020 .026 .025 .028 .028 .033 Income .001 .006 .008 .008 .007 .046 -.055 .037 -.055 -.065 .040 -.063 .057 .022 .090** .057 .022 .095** Newspaper use .021 .014 .057 .007 .013 .019 Internet news .060 .021 .103** .074 .018 .148** .244 .020 .426** .232 .022 .404** -.003 .021 -.004 -.033 .023 -.059 .130 .021 .231** .096 .021 .182** .039 .106** .161 .039 .147** Parent's mean education TV News use (local and network) use Parental Polical Involvement Family Talk Learned about politics in school Efficacy R2 Adjusted R2 .119 .408 .398 .341 .330 Political Socialization Patterns 24 Figure 1 Path analysis model examining the mediation effects of knowledge and efficacy on offline political participation for tweens (N=607) showing only significant paths e1 parent e3 .26 knowledge .25 .38 family .24 -.26 .14 offline .32 efficacy .41 .23 school e2 Figure 2 Path analysis model examining the mediation effects of knowledge and efficacy on offline political participation for teens (N=604) showing only significant paths e1 parent e3 .39 knowledge .27 .32 family .30 -.21 .08 .26 efficacy .47 .23 school e2 offline