The Nature of the Research Paper

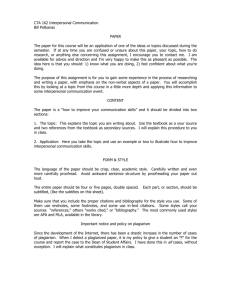

advertisement

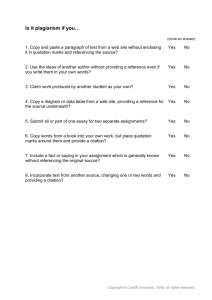

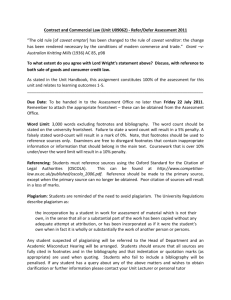

The Nature of the Research Paper Research in the Electronic Age Research Assignment—”OMG, What Should I do Now?” Topic What will I write about? Can I focus on a precise topic? Information How will I find good information? Is everything I need from the library and elsewhere available online on my home computer? Can I use Library Online Databases? What are "primary and secondary sources?" Other than my instructor, who else can assist with the research and writing? Research Assignment—”OMG, What Should I do Now?” (cont’d) Evidence/Evaluation How do I choose appropriate resources? There are thousands upon thousands of books and articles and Web sites on different aspects of the Vietnam War, how do I avoid feeling overwhelmed? How do I evaluate a good resource from a poor one? How do I evaluate evidence to use in my paper? Research Assignment—”OMG, What Should I do Now?” (cont’d) Citation How do I prepare the bibliography/works cited section? How do I cite an article from the ChinaTimes? What about articles from an electronic journal? My uncle fought in the 8-23 Battle. How do I cite a long e-mail message from him relating these experiences? How do I cite government statistics about the War discovered online? What is the most effective way to take research notes? Research Assignment—”OMG, What Should I do Now?” (cont’d) Paper What sections must all research papers include? Should I write an outline first? What about preparing a schedule? Do I include a literature review? What are the differences between databases and indexes and catalogs? How do I know when I've done enough research? When is it time to start writing? How do I avoid accusations of plagiarism? Must I write an executive summary or abstract? Approach to Academic Research Plan. Know the steps involved in any academic project. Action. Do the research. Intuition and/or common sense won't make a research paper appear. Intuition. Insight is of little use without examining appropriate evidence. Intuiting that Alexander the Great was a great general is not enough; research the topic. Common sense. Common sense is not as common as believed and by itself won't produce a research paper. Asserting that something makes common sense, without providing research to prove it, falls short. Types of Research Experimental Research Survey Research Observation Research Naturalistic observation or ethnography Obtrusive or participant observation Case Studies Historical Research Evaluative Research Types of Information Sources (To be Covered next week) Print Materials in Libraries Journal Articles Databases Scholarly Books and Monographs Conference Papers/Proceedings Abstracts Working Papers Citation Indexes Newspapers and News Services Microforms Bibliographies Book Reviews Encyclopedias Reference Titles Online Almanacs Atlases Biographical Information Quotations Dissertations Business Information Statistical Information Archives and Manuscripts Media Sources Govt. Agency Data Other Government/Political Databases Legal Sources Other Resources Bibliographies & Encyclopedias Statistical Information Govt. Agency Data Using the Internet for Research: A Caution Developing the mental framework necessary to successfully deal with such an evanescent tool as the Internet is the researcher's first step. Constant growth keeps the Internet in flux. Greater variability in the quality of information on the Internet differentiates it from traditional library resources. In addition, vast quantities of what can be easily accessed electronically is useless, so researchers must carefully evaluate any document on the 'Net A Step by Step Guide to Researching Your Paper Topic Choice What interests you? Capitalize on your intellectual and knowledge strengths. Use course textbooks Encyclopedias. Browse current periodical shelves Recommendations Conversation Brainstorming Internet Subject headings Example of Generating a Topic Try going into the online database. Do a simple subject search with the word related to your interest. Start with a very broad search in a database. Look carefully at the subject headings and descriptors; ideas to bring the search into focus may be right in front of you. Factors for Topic Selection Interest: Don’t bore others and YOURSELF! Overdone topics. Topics on capital punishment, OCB, CRM, global warming, and other very popular subjects have been covered countless times. If you select any of these issues, choose an innovative angle so your account stands out. Avoid clichés and trite conclusions. Knowledge. Interest in a topic does not necessarily mean you know much about the subject at the outset. The research process mines new knowledge. Factors for Topic Selection (cont’d) Guidelines. Carefully follow the instructor's guidelines. Is the research paper quantitative or qualitative? Will you use survey research methodology or primarily historical research? Follow directions. Breadth of topic. How broad is the topic's scope? Too broad a topic is unmanageable, for example, "The History of Mankind," or "Cancer," "The Influence of Shakespeare on Modern Literature," or "Computers in the Workplace." On the other hand, too narrow and/or trivial a topic, e.g., "My Breakfast", is uninteresting and extremely difficult to research. Focusing on a Topic An Excessively broad topic. "Life and Times of Matthew Arnold." More focused topics. (Though still too broad.) "Poetic Theories of Matthew Arnold," or "An Examination of Matthew Arnold's Views on the Three Main Social Classes in England." Specific and manageable topics. "Imagery in Matthew Arnold's The Scholar Gypsy"; "Matthew Arnold and the Optimal School Curriculum;" "Matthew Arnold and His Idea of the Clergy." Excessively narrow topic. "Matthew Arnold and His Dogs." Select a Realistic Timetable Practical logistics. Allow enough time to choose a sample, to prepare and distribute a survey questionnaire, to wait for the returned questionnaires, to analyze the responses, to write the paper and conclusion. Resources. Have enough resources readily accessible (library, people, museum artifacts, etc.). Very new topics. Is your topic so new that few resources are readily available? Technology makes this less of a problem. However, instructors usually require you to cite many peer-reviewed articles, and very recent topics may cause a problem. It takes time for refereed scholarly articles to appear in print. Select a Realistic Timetable (cont’d) Length of paper. Qualifications. You should be qualified in some way to write about a topic. With no knowledge of Ancient Greek, it is nearly impossible to write a term paper on Ionic and Doric dialect usage in the Homeric epics. Final observation. Most instructors do not allow a student to submit the exact same paper in two courses. Some may allow students to work on an earlier paper, for example, to expand its scope or to bring it up-to-date, etc. The product of this rewrite is essentially a different paper. If you wish to revise a paper written for another course, discuss this with your instructor. Schedule—Set dates for: Topic choice and research proposal. Completion of literature research. Completion of data collection. Completion of data analysis. Fully organized notes. Completion of first, revised and final drafts of paper. Submission of final paper (if no date has been set). Find Background Information If you choose a topic you know very little about, begin by gathering some general background knowledge. Start with your notes, textbooks, reserve reading, and encyclopedias. Decide on Proportion of Resources Determine what use you will make of each of these main resource categories: preliminary, primary, and secondary Online Databases or Print Indexes Remember. Most types of material utilized a couple of decades ago still exist in print format and remain essential resources. All the resources useful for research purposes are not available on the Web. Walk around the libraries. Look at the hundreds of thousands of books and journals. Only a tiny percentage of the full-text contents of these books and journals are accessible electronically. For most research papers in most disciplines it will be necessary to come into the main library (or other libraries) and consult traditional print material. Internet for Other Resources A word of caution. The internet has limitations. Read carefully the material in “Organizing Research Step by Step” on evaluating material found on the Internet. Material within the four walls of any of libraries has been selected by librarians. While occasionally some peripheral items end up on the shelves, most material has scholarly and academic credibility. The immense range of types of material on the Net means it is not always easy to ascertain who authored, published, or posted the material. Some of the material is total rubbish. The fact that a great majority of material on the Net is of more recent vintage also limits the scope of its value. Organizing Research Step by Step Evaluating the Worth of a Resource Be on guard and skeptical when dealing with material found on the Web. Remember the old saying, “Don‘t believe everything you read in print.” (盡信書不如無書) Today, it's "Don't believe everything you read on the Web." Anyone can post anything. There is no filtering or refereeing process. Consequently, all that wonderful, highly valuable research material is often mixed with a plethora of nonsense. Evaluating the Worth of a Resource (cont’d) Be conscious of the differences between print and electronic documents. There are many electronic versions of print journals. Sometimes the electronic version is not as complete as the original print document and may contain errors or omit tables, graphs, and pictures. Evaluating the Worth of a Resource (cont’d) Authorship The author's academic background, experience in the discipline, and previous publications provide useful clues about the quality of the source. Check one of the citation indexes. Have other authors cited this particular author and her/his work? Scholars sometimes cite another author's work as an egregious example of poor research. Generally, however, the more frequently cited works do possess some merit. Authorship Ask: Is the author of the Web or print document qualified to write on this topic? Who wrote the item? (No author listed? Then wonder why.) Recognize the author's name? Read anything else by her or him? Has your professor mentioned this author? Have other types of publications made references to this author? Scholars often cite other good authors. Is the information provided merely the author's opinion? Do the author's credentials, education, position held, age, experience relate to the topic? Authorship Ask: Has the author written a book in this area? Do an author search in online library to find books by the author. Check appropriate database(s) for any written articles. Is the author the original creator of the piece? Has the author provided ways to be contacted? Phone, e-mail, etc.? Is there a Mail-To link? Any details about her or his research methods? Can you be sure that the document was not composed by someone who probably has little authority in the field? Is anonymous data from an electronic newsgroup of any worth? Evaluating the Worth of a Resource (cont’d) Objective Reasoning Ask: Is the information in the source a fact, an opinion or propaganda? Is the information well researched? Or is it questionable and not based on reasonable evidence? Is the language inflammatory or full of bias? Evaluating the Worth of a Resource (cont’d) Personal Biases Acknowledge your own personal biases and how they influence perceptions of others' writings, results, and research. People tend to consult material they find congenial, i.e., material that supports their viewpoints. Creationists, for example, may tend to read more articles by those who disbelieve theories of evolution, and so on. Evaluating the Worth of a Resource (cont’d) Date of Publication For Web material, ask: When was the research gathered and the piece first composed? When was the site last revised and updated (look at the end of the page)? Is a copyright date provided? If the author provides any links, do they work, and if so, are they up-to-date? If the links do not work, it might indicate the information has not been recently updated. If the piece includes tables, charts, graphs, statistics are dates provided? Writing an Outline Outlines are useful for different reasons at different times. Sketching an outline at the beginning of a research project, even without knowing much about the topic, helps to get you started. Outlines become more useful, as the initial research stages evolve. Don’t fool yourself and hope that just by putting index cards or notes into some logical order and proceeding a good research paper will somehow emerge. Taking Notes Underlining books and articles serves some limited use, but only in small judicious amounts. Take notes instead of underlining. Writing notes reinforces and solidifies the argument's point or quotation. Writing summaries on cards forces you to be succinct, to get "to the point." Don’t trust your memory. Record all research. If you consult twenty or thirty sources you'll never remember who said what. Few researchers have keen photographic memories. Option: Use 4" x 6"index cards to take content notes and 3" x 5" cards for the bibliography. Increasingly, researchers use lap-top computers for notes, though these are not always as convenient or as portable as index cards. Still, lap-tops are getting smaller and handier. PDAs are also particularly useful for notetaking. Taking Notes (cont’d) Always include the relevant citation (don't forget the page number(s) as they are necessary for the footnotes and bibliography), whether you use index cards or a computer. For Internet citations, note the electronic address. Keep a word-processing file of the bibliography, whether you use index cards or a computer. As each source is consulted, keep an alphabetical list for the paper's bibliography. Assign the proper citation to each card or note. Remember: one major point per card. Take a minimalist approach. Don't fill each card or note with all important points or themes in an article, or book, or you will be overwhelmed. Taking Notes (cont’d) Use abbreviations to save space and time. If the research concerns Walt Whitman write W.W. Don't waste time noting well known facts. When reading Mary Smith’s History of World War II do not include that Professor Smith stated that Word War II took place between 1939 and 1945. Too many notes are better than too few. All notes don't have to be used. Carefully distinguish between scholarly interpretation, the personal opinion of an author, and the research facts. Taking Notes (cont’d) Sometimes personal comments are made on the index card, e.g., "electronic commerce is here to stay" or "Romanesque cathedrals are more aweinspiring than Gothic ones." Be sure to label the index card or computer reference with a note: personal interpretation or some similar abbreviation. Otherwise, you might later on mistake your opinion for that of the book or article's author. Write all direct quotations precisely, word-for-word, as the original. Use quotation marks, so it can be recognized as a directly quoted text and not a paraphrase. Failure to put a direct text in quotation marks or to credit the author sets the stage for plagiarism. Taking Notes (cont’d) Avoid copying too many direct quotations. Take down the substance of the author's idea in your own words, i.e. paraphrase. Most of the paper should be primarily in your own words with appropriate documentation of others’ ideas. Do not take too many notes from just a single source or two. Admittedly some sources will be more valuable than others; one source in particular may support your thesis or argument. Still, always provide evidence you consulted and used a wide range of resources. Write a headline in capitals on the top of each card. Succinctly indicate the card’s main subject-matter. Arrange the cards in a logical sequence to reflect the paper’s main organization. Taking Notes (cont’d) For a contentious topic, present as equally as possible opposing positions. Be objective. Do not overemphasize one side. Always note the book's or journal's call number for future reference. If you have used different libraries, jot the name of the library where you located the source and took notes. Stop Researching It is impossible to thoroughly cover every facet of the research question and to read all the secondary literature. Know when to quit, when to stop collecting data, and to look for fresh leads. Know when to begin writing. Design a comprehensive research proposal with a well-planned schedule to minimize writer’s block and procrastination. Plagiarism Plagiarism is taking another’s work and passing it off as your own. We all do it each day when we take ideas from others without acknowledging the original source. However, more often than not, we don’t even know the original source. And even if we did, generally we do not make a point of attributing routine quotes of others. Plagiarism in research is quite different. True plagiarism is stealing. Different Types of Plagiarism Copy text. Quotation. A direct quotation from an author must be placed in quotation marks and then referenced in the bibliography or works cited. Forgetting quotation marks could result in accusations of plagiarism. Paraphrase. Paraphrasing another’s passage but doing a poor job of it by keeping very close to the original text is not genuine paraphrasing. Also, paraphrasing a passage or presenting someone else’s ideas in their own words, but failing to give the proper references or citations to the original author is cheating. A Step by Step Guide to Writing Your Research Paper Writing the First Draft Go back to your outline. Read it carefully. Ask yourself, does it still make sense? Read over your research notes. Arrange them in logical order. Keep the topic and the requirements of the paper in mind. Some notes fit the introduction; others support the argument's affirmative position; still others challenge the thesis. Selecting the Audience Brevity, logic, and clarity always strengthen a paper as does omitting unnecessary jargon and avoiding emotional expressions and excitable tones. Don't assume everyone shares your interest in the topic. Your challenge is to generate interest in your readers. Avoid abstruse language and convoluted structures. Always ask a friend or classmate to critique your paper. Don’t try to impress your instructor with excessive sources, materials, and too many quotes. Customary Parts of a Research Paper Refer to the textbook Revising Your Paper Time to Revise Thesis/Argument Organization and Coherence of the Paper Revise the Paper with a Word Processing Program Proofreading Text Presentation