lecture 1

advertisement

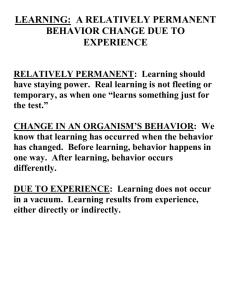

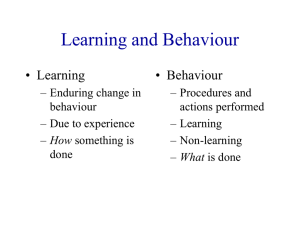

PSYCHOLOGY 2250 LEARNING Definition of Learning: In defining learning we could refer simply to overt behavior. For ex., if I see you riding a bicycle I can assume that you’ve learned that skill. Definition of Learning: In defining learning we could also refer to an internal state of knowledge. For ex., you all know the 10 provinces (but I can’t tell that just by looking at you). So, behavior, or performance, is important. A good definition of learning should have both components: Overt behavior and internal state of knowledge Learning as knowledge acquisition Animals learn about stimuli in their environment Such stimuli serve as signals for some important outcome for ex., a particular odor could indicate that there is food or a predator nearby. Animals also learn about their own behavior A certain action will produce a particular outcome for ex., running to escape from a predator Usually both types of knowledge occur together. For ex., an animal detects a certain odor that tells it a predator is nearby and this odor evokes an escape response, namely running, to avoid being attacked by the predator. Learning: is an inferred change in the organisms’ mental state which results from experience and which influences in a relatively permanent fashion the organisms’ potential for subsequent adaptive behavior. Why is learning defined this way? Key components to definition of Learning 1. Learning is inferred from performance. If there is no behavior to observe then we can’t say for sure whether or not learning has occurred. 2. Learning involves a change in the mental state of an organism We can’t see the neurological structures that underlie this mental state but, in theory, they must exist. Acquired knowledge must somehow be coded or represented in the brain. 3. Learning stems from experience This distinguishes learning from instinct, which refers to behaviors present at birth (i.e., imprinting in certain species of birds) Key components to definition of Learning 4. Learning is relatively permanent Learning persists through time. This part of the definition guards against mistaking a temporary change in behavior, due to fatigue for example, for real learning. 5. Learning is a change in the potential to behave. An animal could acquire knowledge and yet not perform in such a way as to demonstrate that knowledge. The organism could have the potential to behave even though the behavior is not occurring. Other points: Learning is assessed as a change in behavior — this could mean an increase or decrease in behavior For ex., In presence of light — barpress for food In presence of tone — barpress for shock What other things could influence behavior or performance (other than learning)? Fatigue — temporary change so not learning Motivation — maze example; learning occurs but rat not motivated to perform Maturation — could also affect performance but wouldn’t call it learning (i.e., kid reaching cookie jar on top of counter) Domjan’s definition of Learning: Learning is an enduring change in the mechanisms of behavior involving specific stimuli and/or responses that results from prior experience with those or similar stimuli and responses (p. 14) Emphasize distinction between learning and performance fatigue maturation motivation Habituation and Sensitization Much of behavior occurs in response to stimuli, that is, it is elicited, as opposed to spontaneously produced. The simplest form of elicited behavior is reflexive behavior. -knee-jerk reflex -a loud noise causes a startle response -puff of air at the cornea makes the eye blink These are all reflexes. A reflex involves 2 closely related events: -eliciting stimulus -corresponding response The response and stimulus are linked -presentation of the stimulus leads to the response and the response rarely occurs in the absence of the stimulus (i.e., you don’t go around kicking your leg out unless someone taps you on the knee). The specificity of the relation between stimulus and response is a consequence of the organization of the nervous system. Simple reflexes involve three neurons: (1). Sensory— afferent— to spinal cord (2). Motor— efferent— to muscles (3). Interneuron — sensory and motor neurons often don’t communicate directly. This is known as the reflex arc (see Fig. 2.1) Other forms of elicited behavior Two of the simplest and most common forms of behavioral change are: (1). Habituation—defined as a progressive decrease in the vigor of an elicited response that may occur with repeated presentations of the eliciting stimulus. (2). Sensitization— defined as an increase in the vigor of elicited behavior that may result from repeated presentations of the eliciting stimulus. Habituation and Sensitization occur in a wide variety of response systems and are therefore fundamental properties of behavior. Because elicited behavior involves a very close relationship between the eliciting stimulus and the resulting response, people often think that the behavior is invariant, or fixed. The common assumption is that elicited behavior will occur the same way every time the stimulus is presented--not true! Behavior is plastic — it changes— it does not occur the same way every time. Procedures used to study Habituation and Sensitization (examples of repeated stimulation): 1. Visual attention in human infants In babies, visual cues elicit a looking response which can be measured by how long an infant keeps her eye on one object before shifting her gaze. A study by Bashinski, Werner & Rudy (1985)-described on p. 37 of Domjan. 2. Startle response in rats A study by Davis (1974)-described on p.38 of Domjan The startle response is a defensive response in many species (i.e., present loud noise, you jump). In rats, we can measure startle in a stabilimeter chamber Rat jumps, chamber bounces and sensors detect the amount of movement Davis investigated startle in rats by presenting a loud tone. 2 groups of rats -each received 100 tones at 30 sec intervals (110-dB) -noise generator that provided background noise Group 1 soft background noise (60-dB) Group 2 loud background noise (80-dB; not as intense as the tone) Results: Repeated presentations of the tone did not always elicit the same response With soft background noise, repetitions of the tone resulted in weaker startle response (i.e., habituation) In contrast, when the background noise was louder, repetitions of the tone resulted in a bigger startle response (i.e., sensitization) With the same tone, see 2 different patterns depending on other circumstances. These 2 studies show that increases or decreases in responding can occur with repeated presentations of stimuli Decreases in responsiveness by repeated stimulation = Habituation Increases in responsiveness by repeated stimulation = Sensitization Lots of everyday example: grandfather clocks, trains Habituation is a decline in the response that was initially elicited by a stimulus However, habituation is not the only effect that can produce a decrease in response Must distinguish habituation from: response fatigue muscles become incapacitated by fatigue sensory adaptation sense organs become temporarily insensitive (i.e.,won’t respond to visual cues if you’re temporarily blinded by a bright light) Habituation is stimulus-specific -if you present a different stimulus, the animal will make the response -shows that they are not fatigued if they can still make the response -rules out response fatigue Habituation is response-specific -an animal may stop responding to a stimulus in one aspect of its behavior but continue to respond in other ways -e.g., orienting response to mother’s voice may habituate but still listen to what she is saying -rules out sensory adaptation Sense organ Sensory neuron Central Nervous System Site of sensory adaption Muscle Site of response fatigue Motor neuron Site of habituation and sensitization Dual-Process Theory Habituation and Sensitization effects are changes in behavior or performance But what factors are responsible for such changes? The Dual-Process Theory (Groves & Thompson, 1970) was an attempt to get at this issue The DPT assumes that different types of underlying neural processes are responsible for increases and decreases in response to stimuli. The habituation process produces decreases in responding The sensitization process produces increases in responding These 2 processes are not mutually exclusive— they may be activated at the same time. The behavioral outcome depends on which process is stronger. Net effect = summation of habituation and sensitization processes (not to be confused with habituation and sensitization effects) process = underlying neural process/mechanism effect = behavior (what you actually observe) if you observe habituation, might still have sensitization process activated, but its not very strong Groves & Thompson suggested that habituation and sensitization processes occur in different parts of the nervous system. Habituation processes are assumed to occur in the S-R system -the shortest neural path connecting the stimulus and the response (sense organs and muscles) -similar to the reflex arc Each presentation of the stimulus activates the S-R system and causes some build up of habituation Sensitization processes are assumed to occur in the state system -this system consists of other parts of the nervous system that determine the organism’s general level of responsiveness or readiness to respond -only arousing events activate state system; not necessarily activated with every stimulus presentation. The state system determines the animal’s readiness to respond, whereas the S-R system enables the animal to make the specific response that is elicited by the particular stimulus Changes in behavior that occur with repeated presentations of a stimulus reflect the combined actions of the S-R and state systems Back to Startle Response in rats: When the rats were tested with the quiet background noise, there was little to arouse them – the state system was probably not activated - repeated presentations of the tone activated only the S-R system and the result was habituation of the startle response When the rats were tested with the loud background noise, the state system was activated and the result was an increase in the startle response to the same tone. The State and S-R systems are activated differently by repeated presentations of a stimulus The S-R system is activated every time a stimulus elicits a response -it is the neural circuit that conducts impulses from sensory input to response output The state system only becomes involved in special circumstances -e.g., when stimulus is intense Characteristics of Habituation and Sensitization Time course Sensitization is usually temporary -sensitization can last for up to a week but not generally a longterm effect. -with a stronger stimulus, the effects last longer. Habituation can be short-term or long-term, depending on presentation and interval between stimuli. Short-term habituation: -rapid presentations of a stimulus with a short interval between presentations -results in habituation quickly but see spontaneous recovery -the degree of spontaneous recovery depends on length of rest interval. Long-term habituation: -one stimulus presentation a day -see more long-term effects -see less spontaneous recovery Tones Once a Day Tones Tones Every 3 seconds on 1 day Blocks of 30 Tones Leaton, 1976; see page 46 of Domjan Tones Once a Day Tones Stimulus specificity Habituation is stimulus-specific -if you change the stimulus, see recovery of the response Sensitization is not highly stimulus-specific -if an animal is aroused, it is usually aroused to a variety of cues Effects of strong extraneous stimuli If you change the nature of the eliciting stimulus you see recovery of the habituated response. Can also see recovery of the response if the animal is given a rest period = spontaneous recovery. The response can also be restored by presenting a strong stimulus— this is called dishabituation. Dishabituation refers to recovery of the response to the habituated stimulus following presentation of a different, novel stimulus.