Value of Pre-hospital Videolaryngoscopy

advertisement

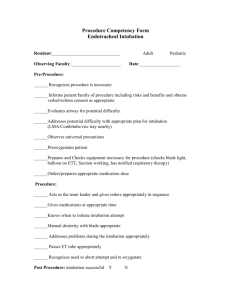

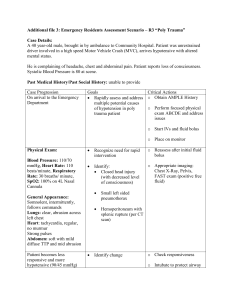

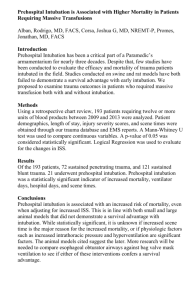

Videolaryngoscopy: Should this be the Standard of Care for Emergency Intubations: What is the Evidence Joseph E Pellegrini, PhD, CRNA Conventional Laryngoscopy Conventional laryngoscopy depends on achieving a “line of sight” from operator to glottic inlet with a recommendation to place patient in a traditional sniffing position. Sniffing position results in optimum alignment of the three axes Oral ---Pharyngeal---laryngeal to achieve a “line of site” 1-4% of all cases this is very difficult to achieve or impossible Often you cannot predict these difficult or impossible cases o Many of these intubations are effectively “blind” requiring increased neck extension, external laryngeal manipulation or the use of a gum elastic bougie Conventional Larygoscopy Conventional laryngoscopy requires flexing of the lower cervical spine and extending the atlantooccipital joint Line of Site Line of Site – Traditional Laryngoscopy Easy to lose Line of Site Often morbidity secondary to poor alignment or technique Videolaryngoscopy Videolaryngoscopy consistently improves the view of the larynx even in conditions where direct laryngoscopy may lead to poor view (i.e. cervical spine cases) Videolaryngoscopy allows the camera to act an “eye” of the operator and is situated in the pharynx of the patient Enables projection of glottis on monitor without the need to anteriorly displace the lower jaw and reduce the cervical spine motion Allows the operator to “see around the corner” Less sympathetic response Less leverage required More easily tolerated in an “awake” patient Videolaryngoscopy Line of Sight PROS - Rothfield Approximately 25 million patients are intubated/year for surgical procedures Overall safety of anesthesia markedly improved with advent of SaO2 and ETCO2 monitoring Morbidity with ETT placement alone ranges from 4-22% Reported decreased morbidity/adverse events with video versus traditional laryngoscopy Multiple studies have shown that using video to assist intubation is effective and reduces morbidity Allows you to “look around the corner” without hyperextending neck etc. CONS - Russo Some studies dispute all positive videolaryngoscopy findings when intubation is performed by experienced anesthesia providers Only effective when used by novices or outside OR’s Anesthesia providers should only use as “backup” to CL? Report decreased effectiveness when video used in face of blood, emesis etc. Can be obscured by sunlight etc. Various publications show that “direct view” does not ensure placement Too angular versus too deep Intubation outside the OR Intubation outside of OR associated with increased morbidity and mortality Data suggest that in-hospital “first pass” intubation success rates varies from 50-98% Most studies evaluated efficacy with anesthesia providers Achieved higher success rates Many “codes” are done without anesthesia presence Limited data Studies indicate increased adverse events in hospital with direct tie-in to survival rates Increased morbidity outside anesthesia specialties Video-laryngoscopy Conventional Laryngoscopy fraught with problems Poor illumination Limited view angle (10-15 ◦) Insufficient view is Number 1 reason for failure both in and out of the OR Especially apparent in NON- ANESTHESIA PROVIDERS Intubations outside operating room often performed by NON ANESTHESIA PROVIDERS in many institutions OB Anesthesia carried CODE BEEPER Sometimes could not respond immediately to code and reliance on emergency room and ICU physicians to facilitate intubation Respiratory therapists presence consistent at all codes Often anesthesia paged emergently to intubate after multiple attempts Study Proposed Glidescope introduced Training provided Comparative study formulated Study efficacy, time to intubate, differences between providers, complications etc. Complication rate: N=105 intubations 3 traumatic bloody airways 1 esophageal intubation No dental trauma Lessons Learned Glidescope difficulties Failure to intubate initially Inability to place tube despite clear visualization o Stylet – need to use GS specific stylet • Flexible stylet o Scope too deep • Pull back ¼” = success Inadequate relaxation o Use of succinylcholine versus midazolam versus nothing Over-eager residents o Placing GS using conventional approach Training parameters established Success rates approached 100% in final stages of study Glidescopes purchased throughout hospital and findings presented at corporate level Found to be easier to use than C-MAC and other devices by NON ANESTHESIA PERSONNEL Intubation in the Field Paramedics have been able to intubate in the field since 2003 Endotracheal intubations are essential components of paramedic training Higher survivability in areas where intubation is performed in the field Some problems arise once transported to hospital secondary to: Malpositioned tubes Multiple attempts Experience of paramedic teams Rural versus metro Pre-hospital Intubation Overall intubation success rate 85.3% Average paramedic experience 59.5 months Average number of attempts per paramedic 1.3 (1-2.75) Mean intubation success rate per paramedic was 80.6 ± 22.3 Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Intubations success rate in Baltimore City ranged from 78-98% successful Variability among EMT providers Dependent on trauma versus cardiac arrest Higher success rates noted in cardiac arrest cases EMTs well versed in use of airway adjuncts and alternative airways Varied results in other counties Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Arundel County Intubation success approximately 80% Carroll County Intubation success rates unknown Prince Georges County Intubation success rates unknown but suspected to be 70% Howard County Intubation success rates 64% with a first pass success rate of only 59% Cardiac arrest Multiple co-morbidities documented Ability to study alternative techniques based on CMO for Howard County Interest by Howard County FD, EMT Divisions Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Study Design Implementation of county-wide education for all EMTs Placement of Ranger Glidescopes on all EMT Data collection tool formulated to collect variables of interest Intubation attempts, Time to intubation, Number of EMTs , Rationale for intubation, Success rates Prospective study approved by State of Maryland IRB Howard County IRB Saint Agnes Hospital IRB Governor O’Malley’s office Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Other variables measured Age Gender Mallampati Laryngeal view Number of patients at scene Initial saturation/Vital Signs Final ETCO2 Glidescope Ranger Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations 344 cardiac arrest incidents evaluated 152 intubations evaluated using Videolaryngoscopy 192 intubation evaluated using Conventional laryngoscopy 3 patients could not be intubated Could not ventilate nor intubate 5 patients used alternative techniques 2 King LTD Airway 3 Bag-valve mask Intubation Success (Percentages) 100 95 90 85 80 75 70 65 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 First Attempt Second attempt Third Attempt Videolaryngoscopy Success Rates Overall Success Seaman K., Rothfield K, Pellegrini J. Video Laryngoscopy Improves Intubation Success in Cardiac Arrest and Enables Excellent CPR Quality Percentages of Overall Success Rates 100 90 80 70 60 50 Series1 40 30 20 10 0 Videolaryngoscopy Conventional Laryngoscopy Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Interruption in CPR Mean duration between VL and CL 45.1 seconds (CI 37.1-53.0 seconds) Associated almost exclusively with CL CPR Fraction was 87.5% in VL group in patients where CPR analytics available o CPR was uninterrupted in VL cases which equates to increased survivability Primary reason for intubation 58% cardiac arrest or airway protection Airway protection secondary to drug overdose 35% trauma Automobile accident GSW Other Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Other variables measured Age 54.2 ± 23.6 years Gender 65% male 35% female Laryngeal view 85% Grade 1-2 view on first attempt 10% Grade 4 views 8 Patients required rescue methods with GS Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Initial saturation/Vital Signs 70% no recorded Oxygen saturation initial (on arrival to scene) Final Saturation levels (on arrival to ED) 49% had no recorded saturation levels 51% had recorded saturation levels ranging from 85% to 100% Final ETCO2 Median ETCO2 levels 25 mmHg 60% of population had ETCO2 < 30 mmHg Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Tube properly placed on arrival to ED 97% ratio of tube properly placed on arrival to ED 37% increase Other Complications Inappropriate tube size attempts 6 ETT required placement using smaller tube Fogging of lens Inability to adequately displace tongue Cords clearly visible but unable to place tube Aspiration 52% reported aspiration present on initial laryngoscopy o 22% blood o 23% gastric contents o 7 % foreign material Maryland Data – Pre-hospital Intubations Plans for Future Studies Other Counties Refined educational tools New standards for troubleshooting National implications Expansion All first responders Survival Data Did not measure survival ratios New code mantra ETCO2 Intubation attempts No disruption of CPR reported when GS was used Study Subjects Design Results (time to intubation) Comments Anderson, Rovsing, & Olsen, 2011 100 morbidly obese pts with BMI >35 (50 in glidescope group and 50 in DL group) RCT, providers had experience with at least 20 glidescope intubations DL: 32 sec VL: 48 sec Glidescope intubation lasted slightly longer, but was of no clinical significance because there were no significant drops in SpO2 in either group. DL intubations were rated as more difficult than VL intubations, and DL intubations required significantly more lifting force. No difference in postoperative sore throat. Ndoko et al, 2008 106 morbidly obese patients with BMI >35 (53 pts in each group) RCT, intubations performed by providers skilled in both techniques DL: 56 sec VL: 24 sec Better maintenance of SpO2 levels with VL compared to DL. Greater increase in MAP, heart rate, and bispectral index number was seen with the DL group. More intubations were rated as difficult in the DL group, and there was a higher incidence of postoperative sore throat in this group as well. Ranieri, Filho, Batista, & do Nascimento, 2012 132 morbidly obese pts with BMI >35 (DL: 64pts, Airtraq VL: 68 pts) RCT, all intubations performed by anesthesiologists highly experienced in both VL and DL DL: 37 sec VL: 14 sec Improved vocal cord view and faster time to intubation with the VL as compared to Dl. Dhonneur et al 2009 318 morbidly obese pts with BMI >35 (106 in each group of LMA CTrach, Airtraq Laryngoscope (VL), and Macintosh laryngoscope) RCT, intubations performed by senior anesthesiologists experienced in the use of VL DL: 69 sec VL: 29 sec This study also compared the use of a videoscopic intubating LMA, but for our purposes we extrapolated data just from the other 2 groups. VL resulted in less shunting and better arterial O2 saturations as compared to DL. VL allowed for the fastest definitive airway, as compared to both other modalities. Arterial oxygenation was of better quality during use of VL compared to DL. Marrell, Blanc, Frascarolo, & Magnusson, 2007 80 morbidly obese pts (BMI >35) RCT, all intubations performed by same DL: 93 sec senior anesthesiologist. Laryngoscopy VL: 59 sec was performed with the same videolaryngoscope (MAC 3 blade Airtraq) but in the control group the screen was hidden. Found better view with VL vs DL and faster time to intubate, but no significant difference in lowest SpO2 during intubation Videolaryngoscopy Bottom Line Pros Easier to master than conventional laryngoscope Novice mastery o Can be used by wide variety of professionials & paraprofessionals More easily tolerated than CL in awake patients Less sympathetic discharge “Intubation by committee” More useful in patients with limited mobility or possess a difficult airway Promotes faster time to intubation & less adverse events in morbidly obese patients Cons Technology driven with all inherent problems Enough said Decreases skill in novices Cannot be used in all settings Pellegrini@son.umaryland.edu