GRS LX 700 Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory

advertisement

GRS LX 700

Language Acquisition

and

Linguistic Theory

Week 12.

Language Universals, and the

beginnings of a model

Typological universals

1960’s and 1970’s saw a lot of activity

aimed at identifying language universals,

properties of Language.

Class of possible languages is smaller

than you might think.

If a language has one property (A), it will

necessarily have another (B).

+A+B, –A–B, –A+B but never +A–B.

(Typological) universals

All languages have vowels.

If a language has VSO as its basic word order,

then it has prepositions (vs. postpositions).

VSO?

Adposition type

Yes

No

Prepositions

Postpositions

Welsh

None

English

Japanes

e

Markedness

Having duals implies having plurals

Having plurals says nothing about having duals.

Having duals is marked—infrequent, more

complex. Having plurals is (relative to having

duals) unmarked.

Generally markedness is in terms of comparable

dimensions, but you could also say that being

VSO is marked relative to having prepositions.

Markedness

“Markedness” actually has been used in

a couple of different ways, although

they share a common core.

Marked: More unlikely, in some sense.

Unmarked: More likely, in some sense.

You have to “mark” something marked;

unmarked is what you get if you don’t

say anything extra.

“Unlikeliness”

Typological/crosslinguistic infrequency.

More complex constructions.

[ts] is more marked than [t].

The non-default setting of a parameter.

VOS word order is marked.

Non-null subjects?

Language-specific/idiosyncratic

features.

Vs. UG/universal features…?

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color

terms

(On the boundaries of psychophysics,

linguistics, anthropology, and with issues

about its interpretation, but still…)

Basic color terms across languages.

It turns out that languages differ in how

many color terms count as basic. (blueish,

salmon-colored, crimson, blond, … are not

basic).

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color

terms

The segmentation of experience by speech symbols is

essentially arbitrary. The different sets of words for color in

various languages are perhaps the best ready evidence

for such essential arbitrariness. For example, in a high

percentage of African languages, there are only three

“color words,” corresponding to our white, black, red,

which nevertheless divide up the entire spectrum. In the

Tarahumara language of Mexico, there are five basic color

words, and here “blue” and “green” are subsumed under a

single term.

Eugene Nida (1959)

Berlin & Kay 1969: Color

terms

Arabic (Lebanon)

Bulgarian (Bulgaria)

Catalan (Spain)

Cantonese (China)

Mandarin (China)

English (US)

Hebrew (Israel)

Hungarian (Hungary)

Ibibo (Nigeria)

Indonesian (Indonesia)

Japanese (Japan)

Korean (Korea)

Pomo (California)

Spanish (Mexico)

Swahili (East Africa)

Tagalog (Philippines)

Thai (Thailand)

Tzeltal (Southern Mexico)

Urdu (India)

Vietnamese (Vietnam)

Eleven possible basic color

terms

White, black, red, green, yellow, blue, brown,

purple, pink, orange, gray.

All languages contain term for white and black.

Has 3 terms, contains a term for red.

Has 4 terms, contains green or yellow.

Has 5 terms, contains both green and yellow.

Has 6 terms, contains blue.

Has 7 terms, contains brown.

Has 8 or more terms, chosen from {purple, pink,

orange, gray}

Color hierarchy

White, black

Red

Green, yellow

Blue

Brown

Purple, pink, orange, gray

Even assuming these 11 basic color terms, there should

be 2048 possible sets—but only 22 (1%) are attested.

Color terms

Jalé (New Guinea) ‘brilliant’ vs. ‘dull’

Tiv (Nigeria), Australian aboriginals in

Seven Rivers District, Queensland.

BWRG

Ibibo (Nigeria), Hanunóo (Philippines)

BWRY

Ibo (Nigeria), Fitzroy River people (Queensland)

BWRYG

Tzeltal (Mexico), Daza (eastern Nigeria)

BWRYGU Plains Tamil (South India), Nupe (Nigeria), Mandarin?

BWRYGUO Nez Perce (Washington), Malayalam (southern India)

BW

BWR

Color terms

Interesting questions abound, including why

this order, why these eleven—and there are

potential reasons for it that can be drawn

from the perception of color spaces which

we will not attempt here.

The point is: This is a fact about Language:

If you have a basic color term for blue, you

also have basic color terms for black, white,

red, green, and yellow.

Implicational hierarchy

This is a ranking of markedness or an

implicational hierarchy.

Having blue is more marked than having (any or

all of) yellow, green, red, white, and black.

Having green is more marked than having red…

Like a set of implicational universals…

Blue implies yellow

Blue implies green

Yellow or green imply red

Red implies black

Red implies white

Brown implies blue

Pink implies brown

Orange implies brown

Gray implies brown

Purple implies brown

L2A?

Our overarching theme:

How much is L2/IL like a L1?

Do IL/L2 languages obey the language

universals that hold of native languages?

This question is slightly less theory-laden

than the questions we were asking about

principles and parameters, although it’s

similar…

To my knowledge nobody has studied L2

acquisitions of color terms…

Question formation

Declarative: John will buy coffee.

Wh-inversion: What will John buy?

Wh-fronting: What will John buy?

Yes/No-inversion: Will John buy coffee?

Greenberg (1963):

Wh-inversion implies Wh-fronting.

Yes/No-inversion implies Wh-inversion.

Wh-inversionWh-fronting

English, German: Both.

Japanese Korean: neither.

John will buy what?

Finnish: Wh-fronting only.

What will John buy?

What John will buy?

Unattested: Wh-inversion only.

*Will John buy what?

Y/N-inversionWh-inversion

English: Both

Japanese: Neither

John will buy coffee? John will buy what?

Lithuanian: Wh-inversion only.

Will John buy coffee? What will John buy?

John will buy coffee? What will John buy?

Unattested: Y/N-inversion only.

Will John buy coffee? What John will buy?

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth

(1989)

L1: Korean (4), Japanese (6), Turkish (4)

L2: English

Note L1s chosen because they are

neither/neither type languages, to avoid

questions of transfer.

Subjects tried to determine what was

going on in a scene by asking questions.

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth

(1989)

Example Y/N Qs:

Did she finished two bottle wine?

Is Lou and Patty known each other?

Sue does drink orange juice?

Her parents are rich?

Is this story is chronological in a order?

Does Joan has a husband?

Yesterday is Sue did drink two bottles of

wine?

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth

(1989)

Example Wh-Qs:

Why Sue didn’t look solution for her problem?

Where Sue is living?

Why did Sue stops drinking?

Why is Patty’s going robbing the bank?

What they are radicals?

What Sue and Patty connection?

Why she was angry?

Eckman et

al. (1989)

wh-inv

whfronting?

results

%

Whinv

%

Whfr

SM K

25

NO

100

YES

UA

T

54

NO

100

YES

TS

J

70

NO

100

YES

MK K

80

NO

100

YES

RO J

88

NO

100

YES

KO

J

95

YES

100

YES

MH J

95

YES

100

YES

NE

T

95

YES

100

YES

SI

J

95

YES

100

YES

G

T

100

YES

100

YES

MA T

100

YES

100

YES

ST

J

100

YES

100

YES

TM

K

100

YES

100

YES

YK

J

100

YES

100

YES

%

Eckman et

al. (1989)

YN-inv.

wh-inv.?

results

YNinv

%

WHinv

SM

K 8

NO

25

NO

MK

K 38

NO

80

NO

YK

J 51

NO

100 YES

TS

J 67

NO

70

TM

K 83

NO

100 YES

RO

J 85

NO

88

BG

T 86

NO

100 YES

MA

T 88

NO

100 YES

UA

T 91

YES

54

NO

KO

J 93

YES

95

YES

MH

J 95

YES

95

YES

NE

T 100

YES

95

YES

SI

J 100

YES

95

YES

ST

J 100

YES

100 YES

NO

NO

Eckman, Moravcsik, Wirth

(1989)

Yes/no inversion

Wh-inversion

Yes (VS)

No (SV)

Yes (VS)

5

4

No (SV)

1

4

Eckman’s Markedness

Differential Hypothesis

Markedness. A phenomenon or structure X in some

language is relatively more marked than some other

phenomenon or structure Y if cross-linguistically the

presence of X in a language implies the presence of Y,

but the presence of Y does not imply the presence of X.

Duals imply plurals.

Wh-inversion implies wh-fronting.

Blue implies red.

Markedness Differential

Hypothesis

MDH: The areas of difficulty that a second

language learner will have can be predicted on the

basis of a comparison of the NL and TL such that:

Those areas of the TL that are different from the NL and

are relatively more marked than in the NL will be difficult;

The degree of difficulty associated with those aspects of

the TL that are different and more marked than in the NL

corresponds to the relative degree of markedness

associated with those aspects;

Those areas of the TL that are different than the NL but

are not relatively more marked than in the NL will not be

difficult.

MDH example:

Word-final segments

Voiced obstruents

Voiceless obstruents

Sonorant consonants

Vowels

most marked

Surge

Coke

Mountain

least marked

Coffee

All Ls allow vowels word-finally—some only allow vowels.

Some (e.g., Mandarin, Japanese) allow only vowels and

sonorants. Some (e.g., Polish) allow vowels, sonorants,

but only voiceless obstruents. English allows all four

types.

Eckman (1981)

e

e

IL form

[b p]

[b bi]

[rt]

[w t]

[sIk]

Mandarin L1

Gloss

IL form

Tag

[tæg ]

And

[ænd ]

Wet

[w t]

Deck

[dk]

Letter

[lt r]

Bleeding

[blidIn]

e

e

c

c

e

Spanish L1

Gloss

Bob

Bobby

Red

Wet

Sick

MDH example:

Word-final segments

Voiced obstruents

Voiceless obstruents

Sonorant consonants

Vowels

most marked

Surge

Coke

Mountain

least marked

Coffee

Idea: Mandarin has neither voiceless nor voiced obstruents in

the L1—using a voiceless obstruent in place of a TL voiced

obstruent is still not L1 compliant and is a big markedness

jump. Adding a vowel is L1 compliant. Spanish has voiceless

obstruents, to using a voiceless obstruent for a TL voiced

obstruent is L1 compliant.

MDH and IL

The MDH presupposes that the IL obeys

the implicational universals too.

Eckman et al. (1989) suggests that this is at

least reasonable.

The MDH suggests that there is a natural

order of L2A along a markedness scale

(stepping to the next level of markedness is

easiest).

Let’s consider what it means that an IL

obeys implicational universals…

MDH and IL

IL obeys implicational universals.

That is, we know that IL is a language.

So, we know that languages are such that

having word-final voiceless obstruents implies

that you also have word-final sonorant

consonants, among other things.

What would happen if we taught Japanese L2

learners of English only—and at the outset—

voiced obstruents?

Generalizing with

markedness scales

Voiced obstruents

Voiceless obstruents

Sonorant consonants

Vowels

most marked

Surge

Coke

Mountain

least marked

Coffee

Japanese learner of English will have an easier time at

each step learning voiceless obstruents and then voiced

obstruents.

But—if taught voiced obstruents immediately, the fact that

the IL obeys implicational (markedness) universals

means that voiceless obstruents “come for free.”

Nifty!

Does it work? Does it help?

Answers seem to be:

Yes, it seems to at least sort of work.

Maybe it helps.

Learning a marked structure is harder. So, if

you learn a marked structure, you can

automatically generalize to the less marked

structures, but was it faster than learning

the easier steps in succession would have

been?

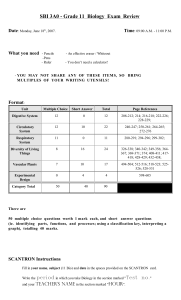

Change from pre- to post-test

Eckman, Bell, & Nelson (1988)

8

7

6

Subj Group

Obj Group

O.P. Group

Controls

5

4

3

2

1

0

Subj

Obj

O.P.

The Noun Phrase

Accessibility Hierarchy

Keenan & Comrie (1977) observed a hierarchy among the

kinds of relative clauses that languages allow.

The astronaut [(that) I met yesterday].

Head noun: astronaut

Modifying clause:

(that/who) I met — yesterday.

Compare: I met the astronaut yesterday.

This is an object relative because the place where the head

noun would be in the simple sentence version is the object.

The Noun Phrase

Accessibility Hierarchy

There are several kinds of relative clauses, based

on where the head noun “comes from” in the

modifying clause:

The astronaut…

[I met — yesterday]

[who — met me yesterday]

[I gave a book to —]

[I was talking about —]

[whose house I like —]

[I am braver than —]

object

subject

indirect object

obj. of P

Genitive (possessor)

obj. of comparative

The Noun Phrase

Accessibility Hierarchy

Turns out: Languages differ in what

positions they allow relative clauses to be

formed on.

English allows all the positions mentioned

to be used to make relative clauses.

Arabic allows relative clauses to be

formed only with subjects.

Greek allows relative clauses to be

formed only with subjects or objects.

Resumptive pronouns

The guy who they don’t know whether he wants to

come.

A student who I can’t make any sense out of the

papers he writes.

The actress who Tom wondered whether her

father was rich.

In cases where relative clause formation is not

allowed, it can sometimes be salvaged by means

of a pronoun in the position that the head noun is

to be associated with.

NPAH and resumptive

pronouns

Generally speaking, it turns out that in languages which do

not allow relative clauses to be formed off a certain

position, they will instead allow relative clauses with a

resumptive pronoun in that position.

Arabic: allows only subject relative clauses. But for all

other positions allows a resumptive pronoun construction,

analogous to:

The book that John bought it.

The tree that John is standing by it.

The astronaut that John gave him a present.

NPAH

The positions off which you can relativize

appears to be an implicational hierarchy.

Lang.

Arabic

Greek

Japanes

e

Persian

SUB

–

–

–

DO

+

–

–

IO

+

+?

–

OP

+

+?

–

GEN OCOMP

+

+

+

+

+/ –

–

(+)

+

+

+

+

Noun Phrase Accessibility

Hierarchy

More generally, there seems to be a

hierarchy of “difficulty” (or

“(in)accessibility”) in the types of relative

clauses.

A language which allows this…

Subj > Obj > IO > OPrep > Poss > OComp

Noun Phrase Accessibility

Hierarchy

More generally, there seems to be a

hierarchy of “difficulty” (or

“(in)accessibility”) in the types of relative

clauses.

A language which allows this…

Will also allow these.

Subj > Obj > IO > OPrep > Poss > OComp

Noun Phrase Accessibility

Hierarchy

More generally, there seems to be a

hierarchy of “difficulty” (or

“(in)accessibility”) in the types of relative

clauses.

A language which allows this…

Will also allow these. But not these…

Subj > Obj > IO > OPrep > Poss > OComp

Relation to L2A?

Suppose that KoL includes where the target

language is on the NPAH.

Do L2’ers learn the easy/unmarked/simple

relative clauses before the others?

Do L2’ers transfer the position of their L1 first?

Does a L2’ers interlanguage grammar obey this

typological generalization (if they can relativize a

particular point on the NPAH, can they relativize

everything higher too?)?

NPAH and L2A?

Probably: The higher something is on the NPAH,

the easier (faster) it is to learn.

So, it might be easier to start by teaching subject

relatives, then object, then indirect object, etc. At

each step, the difficulty would be low.

But, it might be more efficient to teach the (hard)

object of a comparison—because if L2’ers

interlanguage grammar includes whatever the

NPAH describes, knowing that OCOMP is possible

implies that everything (higher) on the NPAH is

possible too. That is, they might know it without

instruction. (Same issue as before with the

phonology)

NPAH in L2A

Very widely studied implicational universal

in L2A—many people have addressed the

question of whether the IL obeys the

NPAH and whether teaching aa marked

structure can help.

Eckman et al. (1989) was about this

second question…

Change from pre- to post-test

Eckman, Bell, & Nelson (1988)

8

7

6

Subj Group

Obj Group

O.P. Group

Controls

5

4

3

2

1

0

Subj

Obj

O.P.

Doughty (1991)

Investigating several issues at once:

Effectiveness of type of instruction

Meaning oriented

Rule oriented

Effectiveness of teaching “down the

markedness hierarchy” (teaching a

marked structure and allowing learnerinternal generalization to an unmarked

structure).

Doughty (1991)

Subjects: 20 international students taking

intensive ESL courses, without much prior

knowledge of relative clauses. Average

length of stay in the US was 3.7 months.

Tasks:

Grammaticality judgment

Sentence completion

Doughty (1991)

Subjects were pretested, then over two weeks (10

weekdays) they came in to a computer lab to take

a “language lesson”. Then, immediately

afterwards, subjects were posttested.

In the language lessons, one of three possible

things happened:

Subject got the “meaning oriented treatment”

Subject got the “rule oriented treatment”

Subject got the “control treatment”

Doughty (1991)

Daily lessons were a text of 5-6 sentences

(of a two-week long “story”) containing an

relative clause formed on the object of a

preposition.

This is the book that I was looking for.

Recall: Noun phrase accessibility

hierarchy:

SU > DO > IO> OP > GEN > OCOMP

Procedure…

Three steps:

Skim

Reading for understanding (experimental section)

Scan

Skim: Subjects saw the text for 30 seconds, with

title, first sentence and last sentence

highlighted—this is to “get the idea” of what the

text is about.

Procedure…

Reading for understanding: Each sentence

displayed consecutively at the top of the screen.

Three different possibilities:

MOG: Also saw dictionary help (2m) and semantic

explanations (referents, synonyms) (2m), including

relationship between head noun and relative pronoun.

ROG: Saw a little animated presentation of deriving a

OPREP sentence from two sentences (This is the

book, I was looking for the book, This is the book

which I was looking for)

COG: Saw each sentence, 2.5 minutes.

Procedure…

Scan. Re-scan paragraph in order to be

able to answer two questions about it, then

write out a summary (NL).

CoG

Pretest

S

SU do

IO

OP GE OC

9

+

+

+

+

+

-

8

+

+

-

+

+

-

10

+

-

-

-

-

-

13

+

-

-

-

-

-

12

-

-

-

-

-

-

11

-

-

-

-

-

-

S

SU do

IO

OP GE OC

3

+

+

-

-

-

-

5

+

-

-

+

-

-

21

+

-

-

+

-

-

7

+

-

-

-

-

-

S

SU do

IO

OP GE OC

2

+

-

-

-

-

-

17

+

+

-

-

+

-

6

+

-

-

-

-

-

20

+

-

-

-

-

-

4

+

-

-

-

-

-

15

+

-

-

-

-

-

1

-

-

-

-

-

-

19

-

-

-

-

-

-

14

-

-

-

-

-

-

16

-

-

-

-

-

-

MOG

ROG

CoG

Posttest

S

SU do

IO

OP GE OC

9

+

+

+

+

+

+

8

+

+

+

+

+

+

10

+

+

-

+

-

-

13

+

-

-

-

+

-

12

+

-

-

-

-

-

11

-

-

-

-

-

-

S

SU do

IO

OP GE OC

3

+

+

+

+

+

+

5

+

+

+

+

+

+

21

+

+

+

+

+

+

7

+

+

+

+

+

+

S

SU do

IO

OP GE OC

2

+

+

+

+

-

-

17

+

+

+

+

+

+

6

+

+

+

+

-

-

20

+

+

-

+

+

+

4

+

-

-

-

-

-

15

+

+

-

-

-

-

1

+

+

-

-

-

-

19

+

+

+

+

-

-

14

+

-

-

-

-

-

16

+

-

-

-

-

-

MOG

ROG

Group mean gain scores

40

MOG

ROG

CoG

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

SU

DO

IO

OP

GEN

OC

Results

Both experimental groups showed strong positive effects

(“Second Language Instruction Does Make a Difference”).

The control group did too (simply from exposure) but not

as dramatic.

Both types of instruction appear to be equally effective

with respect to gain in relativization ability.

Comprehension-wise, MOG scored 70.01 vs. ROG’s 43.68

and CoG’s 40.64. Significant.

Subjects improved basically following the NPAH by being

taught just a marked position.

Comments

Note that:

ROG subjects improved in their ability to

relativize, yet didn’t do so well on the

comprehension tests—meaning isn’t utmost in

getting the structural rules.

MOG subjects got the structural properties

even though not directly instructed in them

(meaning didn’t get in the way).

What about markednessbased shortcuts?

It looks like training them on OPREP

successfully brought subjects to be able to

relativize on everything higher (Subj., Dir. Obj.,

Indir. Obj.).

But mysteriously, many people also seemed to

get OCOMP by the post-test.

Interlanguage grammars do seem to obey the

typological requirements on languages (NPAH).

Is genitive mis-analyzed in the NPAH typological

work, given that it seems to be gotten early…?

Transfer, markedness, …

Do (2002) looked at the NPAH going the

other way, EnglishKorean.

English: Relativizes on all 6 positions.

Korean: Relativizes on 5 (not OCOMP)

Found a very similar

pattern to what we

saw from Doughty’s

experiment.

S

SU do

IO

OP GE

13

+

+

+

+

+

14

+

+

+

+

-

16

+

+

+

-

-

29

+

+

-

-

-

31

+

-

-

-

-

20

-

-

-

-

-

Transfer, markedness, …

The original question Do was looking at

was: Do English speakers transfer their

position on the NPAH to the IL Korean?

But look: If English allows all 6 positions,

why do some of the learners only relativize

down to DO, some to IO, some to

OPREP?

We haven’t even reached the question of

transfer yet—it looks like they start over.

Subset principle?

A tempting analogy… in some

cases, parameters seem to be

ranked in terms of how

permissive each setting is.

I

E

Null subject parameter

Option (a): Null subjects are permitted.

Option (b): Null subjects are not permitted.

Italian = option a, English = option b.

Reminder: Subset Principle

The idea is

If one has only positive evidence, and

If parameters are organized in terms of

permissiveness,

Then for a parameter setting to be learnable,

the starting point needs to be the subset

setting of the parameter.

The Subset principle says that learners

should start with the English setting of the

null subject parameter and move to the

Italian setting if evidence appears.

I

E

Reminder: Subset Principle

The Subset Principle is basically that learners

are conservative—they only assume a

grammar sufficient to generate the sentences

they hear, allowing positive evidence to serve to

move them to a different parameter setting.

Applied to L2: Given a choice, the L2’er

assumes a grammatical option that generates a

subset of the what the alternative generates.

Does this describe L2A?

Is this a useful sense of markedness?

Subset principle and

markedness

Based on the Subset principle, we’d expect the

unmarked values (in a UG where languages are

learnable) to be the ones which produce the

“smallest” grammars.

Given that in L1A we don’t seem to see any

“misset” parameters, we have at least indirect

evidence that the Subset principle is at work. Is

there any evidence for it in L2A? Do these NPAH

results constitute such evidence?

Subset vs. Transfer

The Subset Principle, if it operating, would say

that L2A starts with all of the defaults, the

maximally conservative grammar.

Another, mutually exclusive possibility (parameter

by parameter, anyway) is that L2A starts with the

L1 setting.

This means that for certain pairs of L1 and L2, where

the L1 has the marked (superset) value and L2 has the

unmarked (subset) value, only negative evidence could

move the L2’er to the right setting.

Or, some mixture of the two in different areas.

NPAH and processing?

At least a plausible alternative to the NPAH results

following from the Subset Principle is just that

relative clauses formed on positions lower in the

hierarchy are harder to process. Consider:

The astronaut…

who [IP t met me yesterday]

who [IP I [VP met t yesterday]]

who [IP I [VP gave a book [PP to t ]]]

who [IP I was [VP talking [PP about t ]]]

whose house [IP I [VP like [DP t ’s house]]]

who [IP I am [AP brave [degP -er [thanP than t ]]]]

SUB

DO

IO

OPREP

GEN

OCOMP

NPAH and processing?

If it’s about processing, then the reason

L2’ers progress through the “hierarchy”

might be that initially they have limited

processing room—they’re working too

hard at the L2 to be able to process such

deep extractions.

Why are they working so hard?

(Well, maybe L2A is like learning calculus?)

NPAH and processing?

Is the NPAH itself simply a result of processing?

The NPAH is a typological generalization about

languages not about the course of acquisition.

Does Arabic have a lower threshhold for

processing difficulty than English? Doubtful.

The NPAH may still be real, still be a

markedness hierarchy based in something

grammatical, but it turns out to be confounded

by processing.

So finding evidence of NPAH position transfer is

very difficult.

Subset problems?

One problem, though, is that many of the

parameters of variation we think of today don’t

seem to be really in a subset-superset relation.

So there has to be something else going on in

these cases anyway.

VT

Yes: √SVAO, *SAVO

No: *SVAO, √SAVO

Anaphor type

Monomorphemic: √LD, *Non-subject

Polymorphemic: *LD, √Non-subject

Mazurkewich (1984)

John gave a book to Mary

John gave Mary a book.

“unmarked”

“marked”

To whom did John give a book? “unmarked”?

Who did John give a book to?

“marked”

Assuming that the second of each pair is marked,

Mazurkewich asked about timing of each in L2A.

But although maybe more languages allow the first of

each pair than the second, the pied-piping example should

make us suspicious. Sounds kind of stilted for being the

unmarked option…

Mazurkewich (1984)

French-->English and Inuktitut-->English

French lacks pied-piping and double-object

constructions.

Inuktitut is different enough that it is hard to

find an analog to either the marked or

unmarked constructions. (or so it is claimed)

Did the L2’ers prefer the unmarked

structures? Did they acquire them first?

Mazurkewich (1984)

French-L1 beginners do appear to “prefer” the

unmarked structures (2-to-1), and the marked

structures gain ground as L2’ers become more

advanced.

But French lacks the marked structure; did they

“start with the unmarked structure” or did they

“start with the structure of their L1”?

As for Inuktitut, they weakly “preferred” the

unmarked structures (beginners 77% to 98%).

Not very dramatic, not very convincing.

Mazurkewich (1984)

Worse, on a different task (“question the italicized

phrase”), although the French speakers showed

a moderate preference for “unmarked” (piedpiping) structures, the Inuktitut speakers

showed a preference for the marked

structure.

However, it could be that the whole experiment

isn’t getting at what we want. The controls

preferred the marked structure 3 or 4-to-1, so

these “unmarked” structures seem to be marked

from a language-internal perspective. Plus, this

Problems so far

If L1 has an “unmarked” value for something

and L2 has a “marked” value, if the L2’er

prefers (or, better, learns more quickly) the

“unmarked” value, it could be either transfer

or reverting to an unmarked value.

The actual marked/unmarked set must be

convincingly chosen—means nothing if

we aren’t actually looking at

marked/unmarked.

Best test would be…

Find a convincing marked vs. unmarked

pair, …

Find an L2 which allows only the marked

option, …

Test speakers of an L1 which also only

allows the marked option, …

…and see if L2’ers use/accept the

unmarked option early on.

Liceras (1985, 1986)

Another potential marked/unmarked

pair:

Allows Ø comp. (marked; English)

Disallows Ø comp. (unmarked; Spanish)

EnglishSpanish

Beginners: 49% acceptance of Ø comp.

Intermediate: 25% acceptance.

Advanced: 9% acceptance.

Looks like transfer (not initial

Schwartz (1993)

Back to the questions:

How is a L2 acquired?

Is L2 knowledge like native knowledge?

Supposing it is, then knowing the rules isn’t really part of

knowing the language.

Of course, you can learn the rules and consciously follow

them. But is that knowing English?

Prepositions are things you don’t end a sentence with.

Strive to not split your infinitives.

Don’t be so immodest as to say I and John left; say John

and I left instead.

Impact is not a verb.

Schwartz (1993)

Schwartz distinguishes two kinds of knowledge:

Learned linguistic knowledge

I want to definitely avoid splitting my infinitives.

Competence

*Who did John laugh after asking whether I spread the

rumor that bought the coffee?

L1A

UG (the range of possible languages/grammars)

LAD (a system for getting from the data to the

particular parameter setting for the target

language—not a conscious process, nor available

to conscious introspection)

PLD (positive input)

Would it help the LAD to get rules explicitly?

(“Use do to avoid stranding tense in Infl”; “Don’t extract

an embedded subject out from under an overt

complementizer”; “You want the other spoon.”)

L2A

If L1AD can’t really use this information, why would

we necessarily think that the rules we learn in

French class are in the right form to “be absorbed”

by the L2AD, if such a thing exists…?

That is: L2 has things about it which can only be

learned with the help of negative evidence (or an

L2AD). Yet this doesn’t guarantee that negative

evidence will help.

How can we tell the difference

between LLK and

competence?

(Well-formulated) parameters have wideranging effects. For example, verb raising:

*X: F question can’t use do-support.

Y: F adverbs ok between V and Obj.

Train subjects on *X. If they reset the

parameter, a) they should “automatically”

know Y as well, and b) they can use

negative evidence.

Schwartz’s model

LAD

KoL

blah blah blah

So why does it seem to be

useful to be taught the rules?

Perhaps—knowing the rules (though it is

LLK) allows you in a way to generate your

own PLD. It’s that PLD, the output of using

the rules, which the “L2AD” can make use

of when constructing KoL.

This might explain the apparent truth that

practicing helps a lot more than just

memorizing the rules…?

Krashen’s “Monitor Model”

An early and influential model of second

language acquisition was the “Monitor

Model”, based on five basic hypotheses:

The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis

The Monitor Hypothesis

The Natural Order Hypothesis

The Input Hypothesis

The Affective Filter Hypothesis

The Acquisition-Learning

Hypothesis

Acquisition and Learning are different.

Acquisition refers to the (subconscious) internalizing of

implicit rules, the result of meaningful naturalistic

interaction using the language.

Learning refers to the conscious process that results in

knowing about the language, e.g., the result of classroom

experience with explicit rules. (LLK)

That is, you can learn without acquiring (or acquire without

learning).

Krashen hypothesizes that learned and acquired rules are

stored differently; one cannot eventually be converted into

the other; they are simply different.

Perhaps, or maybe the speculation on the previous slide was right.

The Natural Order Hypothesis

Acquisition proceeds in a “natural order” (i.e. the

order of morpheme acquisition discussed

earlier).

This says nothing about learning, only

acquisition.

Also: Krashen’s actual hypothesis is based on posthoc analysis of the order L2’er do seem to acquire

these morphemes—there’s no underlying theoretical

machinery. That’s not to say that there couldn’t be

some, of course.

The Monitor Hypothesis

A linguistic expression originates in the

system of acquired knowledge, but prior to

output a “Monitor” checks it against

consciously known rules and may modify

the expression before it is uttered.

Learned

competence

(the Monitor)

Acquired

competence

output

The Monitor Hypothesis

For the Monitor to work, you need to

Be able to focus on the form (time, attention)

Know the rule

So, under pressure (e.g., time pressure), the

Monitor may not be operating…

Learned

competence

(the Monitor)

Acquired

competence

output

The Monitor Hypothesis

The Monitor would probably be the place

where things like “don’t split infinitives” and

“don’t end a sentence with a preposition”

live as well.

Learned

competence

(the Monitor)

Acquired

competence

output

The Input Hypothesis

The Input Hypothesis draws on the Natural

Order Hypothesis; the idea is that there is

a natural order of acquisition, but in order

to advance from one step to the next, a

learner needs to get comprehensible input,

input which provides evidence for the

stage one level past the learners’ current

level. The idea is that only this level of

input is useful for the advancement of

acquisition.

The Input Hypothesis

Krashen’s view on acquisition: Speaking does

not cause acquisition, it is the result of

acquisition, having built competence on the

basis of comprehensible input.

If input is at the right level and comes in

sufficient quantity, the necessary grammar is

automatically acquired.

The language teacher’s main role, then, is to

provide adequate amounts of comprehensible

input for the language learners.

Let’s stick to the model and not the politics here…

Input ≠ intake

Inuktitut—input:

Qasuiirsarvigssarsingitluinarnarpuq

‘Someone did not find a completely suitable

resting place.’

tired cause.be suitable not

someone

Qasu-iir-sar-vig-ssar-si-ngit-luinar-nar-puq

not place.for find completely 3sg

Input ≠ intake

After three long nights of gripning, John finally

found his slipwoggle.

Knowing so much about the rest of the sentence

can tell us quite a bit about the parts we don’t

know yet. (Slipwoggle is a noun, a possessible

thing; to gripen(?) is a verb, a process that one

can perform over an extended period of time). We

can then make use of this to build our language

knowledge (here, vocabulary).

Input ≠ intake

(Krashen) Learner must get comprehensible

input (mixture of structures acquired and

structures not yet acquired) to advance.

Input: What is available to the learner.

Intake: Input that is used in grammarbuilding.

What makes input into

intake?

Apperception: Recognizing the gap between what L2’er

knows and what there is to know.

Comprehensibility: Either the semantic meaning is

determinable or the relevant structural aspects are

determinable.

Attention: Selecting aspects of the knowledge to be

learned (from among many other possible things) for

processing.

Output: Forcing a structural hypothesis, elsewhere used

to shape input into a form useful for intake.

Input apperception

Some input is apperceived, some isn’t.

That which isn’t is thought of as blocked

by various “filters”:

Time pressure

Frequency non-extremes

Affective (status, motivation, attitude, …)

Prior knowledge (grounding, analyzability)

Salience (drawing attention)

The Affective Filter

Hypothesis

Another aspect of the need for

comprehensible input is that it must be “let

in” by the learner. Various “affective”

factors like motivation, anxiety, can “block”

input and keep it from effectively

producing acquisition.

The overall model

Although Krashen’s “Monitor Model”

suffers from a lack of specific testable

details, it has had a significant impact on

L2A research, and has an intuitive appeal.

An interesting idea

(courtesy of Carol Neidle)

If you were to learn French, you would be

taught conjugations of regular and

irregular verbs. Regular -er verbs have a

pattern that looks like this:

Infinitive: donner ‘give’

1sg

je donne 1pl nous donnons

2sg

tu donnes 2pl vous donnez

3sg

il donne

3pl ils donnent

Some French “irregulars”

Infinitive: donner ‘give’

1sg

je donne

1pl

2sg

tu donnes

2pl

3sg

il donne

3pl

nous donnons

vous donnez

ils donnent

Another class of verbs including acheter ‘buy’ is

classified as irregular, because the vowel quality

changes through the paradigm.

Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’

1sg

je cède

2sg

tu cèdes

2pl

3sg

il cède

3pl

1pl

nous cédons

vous cédez

ils cèdent

Some French “irregulars”

Infinitive: donner ‘give’

1sg

je donne

1pl

2sg

tu donnes

2pl

3sg

il donne

3pl

nous donnons

vous donnez

ils donnent

The way it’s usually taught, you just have to

memorize that in the nous and vous form you

have “é” and in the others you have “è”.

Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’

1sg

je cète

1pl

2sg

tu cètes

2pl

3sg

il cète

3pl

nous cédons

vous cédez

ils cèdent

Some French “irregulars”

However, the pattern makes perfect phonological sense in

French—if you have a closed syllable (CVC), you get è,

otherwise you get é.

[sd] (cède)

[se.de] (cédez)

So why is this considered irregular?

Because in English, you think of the sounds in cédez as

[sed.de], due to the rules of English phonology.

Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’

1sg

je cède

2sg

tu cèdes

3sg

il cède

1pl

2pl

3pl

nous cédons

vous cédez

ils cèdent

Some French “irregulars”

Because in English, you think of the sounds in cédez as

[sed.de], due to the rules of English phonology.

Since in all of these cases, English phonology would have

closed syllables, there’s no generalization to be drawn—

sometimes closed syllables have é and sometimes they

have è.

What could we do?

Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’

1sg

je cède [sed] 1pl

2sg

tu cèdes [sed] 2pl

3sg

il cède [sed] 3pl

nous cédons

vous cédez

ils cèdent

[sed.dõ]

[sed.de]

[sed]

Some French “irregulars”

If people are really “built for language” and are able to pick

up language implicitly (as seems to be the case from

everything we’ve been looking at), then if people are

provided with the right linguistic data, they will more or

less automatically learn the generalization.

Problem is: The English filter on the French data is

obscuring the pattern, and hiding the generalization.

Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’

1sg

je cède [sed] 1pl

2sg

tu cèdes [sed] 2pl

3sg

il cède [sed] 3pl

nous cédons

vous cédez

ils cèdent

[sed.dõ]

[sed.de]

[sed]

Some French “irregulars”

Something to try: Provide people with the right data, see if

they pick up the pronunciation. Perhaps: exaggerate

syllabification. (attention) Perhaps try to instill this aspect

of the phonology first.

Et voilà. Perhaps this will make these “irregulars” as easy

to learn as regulars!

The downside: I have no idea if this would actually work.

Infinitive: ceder ‘yield’

1sg

je cède “sed” 1pl

2sg

tu cèdes “sed” 2pl

3sg

il cède “sed” 3pl

nous cédons

vous cédez

ils cèdent

“se—dõ”

“se—de”

“sed”

“Incomprehensible input”

So this is another way in which input might

be “incomprehensible”—not that it is

inherently incomprehensible (i.e. not that it

would be incomprehensible to a L1’er), but

that the prism of the L1 is getting in the

way of seeing the data for what it really is.

Some critiques on record re:

the Monitor Model

Are acquired and learned rules really stored so separately

that they cannot interact? Gass & Selinker’s textbook

points out that “it is counterintuitive to hypothesize that

nothing learned in a formal situation can be a candidate

for [fluent, unconscious speech]”.

But this doesn’t seem to be a very persuasive objection—

First, counterintuitiveness is not an argument. Second,

even if formal, learned rules are stored completely

separately, nothing prevents the use of these rules in

production from providing input to the acquisition system,

providing an indirect “conversion” of knowledge.

Some critiques on record re:

the Monitor Model

G&S also observe (attributing the objection to Gregg)

that in Krashen’s model, the Monitor only affects output

(speech, writing), but anecdotal evidence for use of

formally learned rules in decoding heard utterances is

easy to come by.

Perhaps this is true of Krashen’s particular statement,

but there seems to be no need to toss out all aspects of

his hypotheses based on an oversight of this sort—it

seems easily repairable by extending the model to allow

learned competence to also monitor input and provide

input to the acquired competence.

Of course, Krashen may have meant it, but that’s irrelevant. He’s

one guy with good ideas and bad ideas like anyone.

Some critiques on record re:

the Monitor Model

Most of the objections to the Monitor Model focus on the

impreciseness of the hypotheses; although Krashen may

not have treated them this way, they clearly must be

used only as a starting point, a way to think about the

process of L2A.

Further research in this direction needs to be focused on

trying to refine the existing “hypotheses” to yield testable

(falsifiable) hypotheses with a higher degree of

specificity.