Consumer Law outline 2012 – anonymous

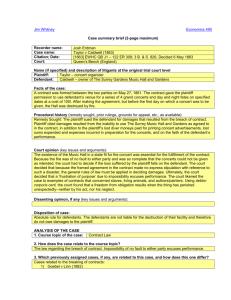

advertisement