Notes-BryanStationWomen-KETinterview

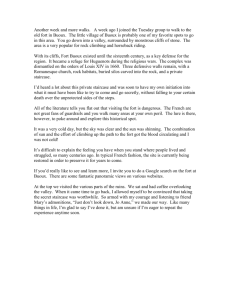

advertisement

We are producing a piece for our Mother's Day episode of Kentucky Life on the Siege of Bryan Station and the resulting Battle of Blue Licks. I was wondering if you might be willing to give a brief interview to help tell the story of the heroic women of Bryan Station and their place in Kentucky history? A station is a defensible residential site - generally smaller than forts but living conditions more pleasant. Stations were privately held and controlled usually by families related by blood, marriage or friendship. The communal labor for clearing a family head's pre-emption right supported the station which was not only for defense during skirmishes but also to keep their horses and cattle from being carried off in the night by raiders. Families would move out when issues of sanitation, crowding or conflicts over moral values (religion, politics) arose. Over 150 stations documented in the 12 counties of the Inner Bluegrass region where settlement was earliest and most intense - but only a few have been verified by archaeological excavation. 75 of those we know about were established during the short 6 years of what archeologists call the “Revolutionary Period” of settlement: 1776-1782. Bryan's Station grew to the size of a fort but continued to be called a station. Bryan's Station was on North Elkhorn Creek in Fayette county about five miles northeast of the fort in Lexington. The site is now on Bryan Station Road, but at the time it was established it was on the path from Lexington to Limestone that became the Lexington-Maysville Pike. It was established in 1779 by the Bryan brothers (William, Morgan, James and Joseph) from North Carolina and William Grant who like Wm Bryan - had married a sister of Daniel Boone. While traveling through the Cumberland Gap, they were joined by two land jobbers, Cave Johnson and William Tomlinson from Virginia. These were second generation settlers, and few of the white families were poor or working-class in those early days since these women could not afford the expensive trip to the west. While the women of the Pennsylvania, Carolina or western Virginia frontiers had long experienced management of a household economy for their families’ sustenance, during the early 1800s their importance as production level workers for their families’ economic success waned. The popular literature of the day showed that the ideal white woman was to serve as a “republican mother” as of the ancient Greek city-states and be the moral compass for their sons who would grow up to be citizens of the New Republic in the agrarian West. Women who helped build the frontier villages and cities of Kentucky however did not always remain tied to a domestic role as prescribed and valorized in the ideal of the republican mother. Records include stories of women evidence military valor during their lives of constant warfare. Most women had to take on the role of frontier warriors but preferred to remain anonymous in the process, and a more acceptable role was publicly to shame men not adequate in their roles in the defense of the community. Women retained the responsibility then for turning the frontier into the civilization of domesticity they once knew or wanted to emulate. Mostly of the middle-class and married (since poor or working-class women could not often afford the expensive trip to the west), they brought with them or ordered from relatives or favorite stores back East the respectable white doilies, elegant china and plated silver for their tables. While Kentucky frontier women kept having babies, working in the fields to clothe and feed their families, they also started up schools when forted and made sure that preachers held church services when they could. Daniel Trabue remembered some women traveling from Forts Harrod and Logan went on a shooting spree but transformed into “Ladys” when they celebrated in fancy dress at George Roger Clark’s new Fort Nelson at the Falls of the Ohio in 1779. In the 1780s the frontierswomen of Strode’s Station (nearby today’s Winchester in Clark County) worked together to produce thirty yards of hemp linen for an old widower.1 Pioneer families often planted flax and hemp right away for domestic production of clothing, cordage, bagging and paper for family consumption or for barter. Women traditionally managed the textile production in the rural home. However, early in Kentucky history, women lost their place in this profitable industry. The richer the pioneer, the more hemp could be grown, manufactured and sold for a hefty profit – and women took advantage of this opportunity in the new frontier. Tax lists for the 1780s and 90s show a surprising number of early pioneer women as well as men owned slaves or had indentured servants who could do the back-breaking work in the hemp and flax fields. By 1780 many of the North Carolinians who started Bryan Station left due to confusion about the land ownership, but soon others from Virginia joined the few who had remained. By 1782 this was the largest station in the state. Like most pioneer stations the population was transient and settlers moved on to their own separate farms as conditions permitted. It probably had a peak population of a few hundred. The fort was described as having 44 log cabins (with clapboard roofs that sloped inwardly) and a twostory blockhouse connected in a 200 yard-by-50 yard parallelogram for defense, with a 12-foot high stockade. One of the cabins was built just to hold a large quantity of dried meat for one of George Rogers Clark’s campaigns – later it was used as a school. Two entrances were guarded by big folding gates that swung on wooden hinges - one on the southeastern side nearest a buffalo trace which developed into the Bryan Station turnpike, and the other on the northeastern side facing the woods and offering a path down the hill to a spring near the North Elkhorn creek. A heavy growth of hemp as well as a hundred acres of corn combined with a vegetable garden to prove the settlers' rights to the land. Baptist pastor Ambrose Dudley held services at Bryan Station, and likely his pastoral care was supported primarily by women and blacks who heard his message of salvation in new ways that helped create America’s Second Great Awakening. Many outhouses surrounded the station for communal uses: tanning vats, rope walks and other industrial purposes. The site of the station is occupied by the 1794 Joseph Rogers house. (Names of the women on the DAR monument: http://genealogytrails.com/ken/bryanstation.html Jemima Suggett Johnson Polly Hawkins Fanny Sanders Lea Betsy Craig Betsy Sunders Betsy Johnson Sally Craig Nancy Craig Lucy Hawkins Elizabeth Johnson Mary Herndon Ficklin Polly Craig Elizabeth Craig Cave Polly Sunders Harriet Morgan Nelson Frankey Craig Polly Cave Lydia Sunders Sally Johnson Hannah Cave Sara Pace Craig Sally Hawkins Sara Clement Hammone Jain Craig Sunders Mildred Davis Suggett Sarah Boone Brooks Lucien Beckner, ed., “Reverend John Dabney Shane’s Interview with Peioneer William Clinkenbeard,” The Filson Club History Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 3 (April 1928) p. 119. 1 March 1782 Wyandot Shawnee struck Strode's Station capturing several African-Americans. Benjamin Logan dispatched 15 men to join Capt James Estill and Lt John South at Estill's Station near Richmond they trailed the Indians to a field on the banks of Hinkston Creek near Mt Sterling and lost 8 men including the 2 officers.A preemptive strike on June 4-5 by Col William Crawford against Delawares and Wyandots on the Sandusky was also a defeat. British officers Caldwell and Alexander McKee of the British Indian Department at Fort Pitt (who had originally owned 2000 acres of land on South Elkhorn which had been confiscated as part of the grant from Virginia to the Transylvania Seminary) with his interpreter-intermediary Simon Girty and 300 British mercenaries and Indian allies (Shawnees, Wyandots, Delawares, Mingoes, Pottawatamis, Ottawas, Miamis and Ojibwas) decided to strike KY settlements in response to the aggressive actions by Kentucky militia and land jobbers. Bryan's Station (5 m north of Lex) took the first blow on August 16th. They arrived on the evening of August 15th and dployed into small group -one group hid in the brush near the spring. The raiders allowed the few settlers outside the fort to continue their business so as not to expose how large a company they were. James McBride killed one of the Indians who was attempting to find out how many men were stationed there - and during the ruckus James Morgan who lived in a cabin nearby strapped his baby to his back, hid his wife under a slab of the cabin floor and ran to the fort. Two men on horses, Thomas Bell and Nicholas Tomlinson, slipped out of the station from the main gate on the souteastern side of the stockade onto the buffalo trace to Lexington to raise the alarm for reinforcements under Col. John Todd. In the morning of the 16th, a plan was devised to send out the women to gather water at the spring on the northern side that faced the cane fields, just like they did every morning. The Indians would not attack because they didn't want to expose themselves by attacking the women. Led by Jemima Suggett Johnson, the mother of an infant son who later grew up to become the ninth Vice President of the United States, Richard Mentor Johnson, 12 women and 16 girls gathered their pails, piggins, noggins and gourds and walked down the hill to the spring, under the watchful eye of the would-be attackers. It took over an hour to fill all the pails and then make the return journey of about 60 yards up the hill and back into the fort with enough water to last several days. After they safely returned to the fort, everyone celebrated, and according to Walter Homan Ficklin, John Craig then assigned them to battle stations. Once everyone was in position with rifles aimed through tiny slit openings in the wall. The raiders sent a small group to fire on the opposite side of the fort, hoping to lure the men out. The settlers understood the ruse and sent several men out to pretend to go after the small band, but as soon as shots were fired, they turned around and quickly ran back inside. Thinking they were catching the settlers off guard they attempted to scale the walls, at which point Craig gave orders to the settlers within the walls, including women and children, to open fire, which they did from their assigned positions. The Indians scattered and ran back to the woods. A few reached the still open gates of the fort, however, and set fire to five of the cabins. The settlers raced to put the fires out and a providential wind came that blew the smoking embers away from the fort. Although the battle continued steadily all day long, the fort was spared the destruction that would have followed a surprise attack. In the afternoon, reinforcements arrived. 30 militia from Lexington and 10 from Boone's Station came to rescue the settlers, but only the 17 on horses succeeded in entering the fort - the rest retreated back to Lexington. Meanwhile Caldwell and the Indians destroyed cabins, livestock and crops of surrounding settlers, trying unsuccessfully to burn the fort down. According to the British account, 300 hogs and 150 head of cattle were killed, the few sheep found were killed and every horse outside the stockade was appropriated. On the morning of August 17th they withdrew. The settlers went out and ate the leftovers of the meat cooked the night before and left behind, and buried their dead - four killed and three wounded according to Boone. The bodies of the 30 of the British forces killed were buried in a mass grave not far from the area used as the burial place for "the negroes of the station" according to Ranck in his 1896 address. On the morning of August 18th Colonel Stephen Trigg arrived at Bryan's Station with 130 Lincoln County militia, joined by Col Daniel Boone, Major Levi Todd, Lieutenant Col John Todd and other militia from Fayette County. They pursued the British/Indian soldiers to the Lower Blue Licks at a horseshoe bend in the Licking River: a death trap. Benj Logan with his 154 men from St. Asaphs did not get there in time to engage with the enemy, but on August 23th went with 470 men to the battlefield where they buried in a common grave 43 stripped and mutilated bodies - none of whom could be positively identified. This was the worst defeat on the western frontier during the American Revolution - but it was also the last major Indian invasion into Kentucky. Clark then joined in with Logan, Floyd and Boone to gather an army of 1050 men to plunder and destroy the abandoned Shawnee town of New Chillicothe. August 1896 Lexington Chapter of the DAR commemoration with historian George Ranck giving address - motto "For Home and Country,' have sounded a note of civilization and inspiration for the better preservation of our historic places and for the payment of the debts of gratitude we owe to the departed men and women who did so much to make us what we are.... And this memorial, may it continue to designate the spot made glorious by the women of Bryan's Station.... and be as everlasting as the hill where the fated Red Men and the indomitable Anglo-Saxons battled for the possession of a garden of the gods. And so enduring, may generations yet to come, mindful of the glorious deed that has consecrated the spot, stand with uncovered heads before this memorial and still be able to trace this inscription which the gratitude and patriotism of women have caused to be graven upon its sides: In Honor of the Women of Bryan's Station, who, on the 16th of August, 1982, faced a savage host in ambush, and with a heroic courage and a sublime self-sacrifice that will remain forever illustrious, obtained from this spring the water that made possible the successful defense of that station. This memorial was erected by the Lexington Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, August 16th, 1896. The Women of ancient Sparta pointed out the Heroic Way -- the Women of Pioneer Kentucky trod it." composed by Ranck http://google.com/books?id=dY6HrmHwbEcC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false In helping to memorialize this part of Kentucky history, Ranck differed from other Progressive historians such as Frederick Jackson Turner, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. or Charles Beard in that they rarely if ever found any place for race or gender in their analysis of American history. But he is clearly in keeping with Turner’s famous 1893 address, “The Significance of the Frontier” which characterizes America’s exceptionalism as the story of strong, motivated, self-reliant settlers taking advantage of the frontier’s seemingly unlimited resources compared to the misery and overcrowded conditions in the East. The historians of this time period were critical to what many now know was a kind of “myth-making” to help assure white Americans of this critical time period of violence and segregation that it was all worth it: Manifest Destiny, Social Darwinism, a national character based on a “frontier psychology” and anyone else, especially those inhabitants in these areas who were of color, became invisible if not recreated as “savages” in the way of the “civilizers”. Black participants in the frontier stories are nameless or ignored, people of mixed race (and there were many by this time) were picked out as villains because of their innate bad characters deriving from their “bad blood.” http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bryant%27s_station.jpg 1851 Print by Nagel & Weingartner