Before Starting a Thesis or Capstone Project

advertisement

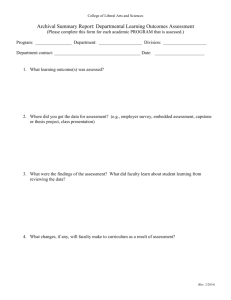

1 MAIR Thesis and Capstone Project Guide Summer/Fall Semester 2014 Revised by Kent Warren, Ph.D. September, 2014 2 GUIDE TO PREPARING A THESIS OR CAPSTONE PROJECT: FROM IDEA TO COMPLETION The following document is designed to help MAIR students select between a capstone project and a thesis as they move toward the end of their master’s degree program. The emphasis is on the planning and producing of the proposal for both efforts as those proposals are critical to the success of the entire thesis or project. There are also sections on doing the thesis and capstone project, but again, the proposals provide the foundation on which everything else is constructed. This guide is designed to walk you through much of the experience of doing your proposal and your thesis or capstone project. It is not structured around your registrations for thesis or capstone project, which are described in another document attached to the end of this document. In general, there are typical registration patterns for both the thesis and capstone project, but variations are always possible for practical, financial, or other personal reasons. The following describes the primary registration patterns and the basic tasks that are connected to each registration. Do remember that we are flexible and tasks and corresponding registrations will vary. Thesis Registration: MAIR 297 Graduate Research (4 credits) This registration can be broken down into 1 to 4 credits over time, but all students must finally complete a total of four credits of MAIR 297. During Graduate Research registration, you would typically complete your thesis proposal and obtain approval from the IRB if you are using human subjects. MAIR 299 Thesis (4 credits) You may have done some of your research for your thesis as part of your Graduate Research, but now is the time to complete your research, write your thesis, and get it approved. If you don’t finish your thesis during your Thesis registration, you would register for Grad 200 until you are finished and have graduated. 3 Capstone Project Registration: Please note that all registrations for the Capstone Project can be broken into smaller number of credits. By the time your project is completed, you will need to have taken the number of credits attached to each registration noted below. MAIR 294 Intercultural Project Design (2 credits) For the design phase of the Capstone Project, you must complete the design of your project and get it approved by your committee. It is possible that you would do some of your project while in the design phase. Please note that during the design phase you can conduct a needs assessment or talk with experts on your topic without having to gain approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB). This is because you are collecting ideas, opinions, thoughts for the sake of the design, not as data to be reported in some form. MAIR 296 Intercultural Project Implementation (4 credits) In the implementation stage, you will carry out the activities you identified in the design stage. For example, you might design and teach a course or conduct a training session. You might develop a manual, write a book, or create a video. The emphasis is always on demonstrating how theory can be applied. In the process of implementing your project, you will need to keep notes or write a journal to help provide the key elements needed for the final analysis. MAIR 298 Intercultural Project Analysis (2 credits) Once the project has been implemented, it will be time for you to move into the last stage where you will analyze what you did and what you learned in the process. The notes or journal mentioned above will provide some of the substance from which you will conduct your analysis. It will also be a time in which you take the literature you covered in the design phase and consider its relationship with the finished product you have implemented. 4 Introduction to the Thesis and Capstone Project Whether or not you are familiar with Douglas Adams’ science fiction classic, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, it does provide an important piece of advice for those exploring the galaxy or even approaching a thesis. On the front cover of the guide in this fantasy of galactic travel are the words: DON’T PANIC! So imagine that they are glowing and flashing right now! The process of doing a thesis or a capstone project often causes students to think: How am I going to organize all this information? It’s got to be perfect! How do I make it perfect? How much is too much research for a thesis? What are all the things I must do in carrying out a project? What should my writing style look like? How will I know when I am done? The best of students sometimes go into a state of near panic in which they forget all that they have learned and much of the common sense that they have developed over their years of life and schooling. But if you remain calm and relaxed, this task will be much easier and more manageable; it might even be fun and exciting. To ease your way into the thesis or capstone project, there are several steps that will help you to establish a sound approach and allow you to move through this process with comparatively few anxieties. Welcome and have a good time! What is a Thesis and What is a Capstone Project? In examining the MAIR program as you started, you undoubtedly saw that MAIR was built on the concept that theory informs practice and practice must inform theory as well. Given this emphasis on theory and practice, we have established two ways of completing our degree program that reflect these differing emphases. First, there is the thesis, which in general stresses the theoretical side of the program. The thesis involves the development of a research question(s) that guides you from design to analysis. You will examine the literature to provide the context in which your research question is being asked. You will decide on methods (such as interviews and focus groups) that will allow you to collect data that address your questions most clearly and fully. Once you have collected your data, you will examine those findings and determine the best way to present that information to the reader. Ultimately, you will use theories, models, and frameworks from the literature, as well as the findings themselves to examine and analyze what you have learned. Throughout, the emphasis will be on the 5 collection of valid and reliable data and the analysis of that data within the context of the research and the context discovered within the literature. Second, there is the capstone project, which places emphasis on the practice side of the program. The capstone project involves the development of a product that can be seen as a logical extension of the theoretical work core to the program. You will design and implement a project that demonstrates your ability to use fundamental concepts, models, theories, etc. in practical ways. At the foundation of your capstone project will be a set of goals and objectives that will guide you from idea formation to implementation. As with the thesis, you will provide a context for your project, but the emphasis will be on literature that supports the goals and practical applications central to your project. The core of the project is the development and presentation of some practical application derived from the theoretical, conceptual base of the intercultural relations program. The presentation may take many forms such as designing and teaching a class or conducting a training program, writing a book relevant to the field, producing a video, or developing and testing an assessment tool. Both the thesis and capstone project are positive and effective ways of completing the MAIR program. Your selection of which to do will happen over time and there will be value in going either direction. For now, learning more about the options is the most productive way to begin. Before Starting a Thesis or Capstone Project Upon entering the program, many students immediately begin to wonder about their thesis and a thesis topic or their capstone project and what it would involve. This is natural. The thesis or capstone project is an important part of most masters’ programs, and some students feel pressure to “get it all together” right from the start. However, it is not at all necessary to begin this process at once. Even those who enter the program with a strong interest often discover other areas that attract them as they move through their studies. There are also practical reasons to avoid choosing a thesis topic or capstone project too soon. For example, it might take time to meet advisors who are a good match for you or discover the kind of research you want to do for a thesis. And a capstone project eventually might be based on a job you haven’t even found yet. As you approach your thesis or capstone project, it is helpful to remember that the program assignments are designed to move you into an understanding of the standards and expectations of scholars and practitioners in the field of intercultural relations. Step by step, the assignments will prepare you to write, to think, to plan, to organize, to apply, and to analyze in ways that will facilitate your thesis or capstone project work. There are approaches that can get in your way and we encourage you to avoid these pitfalls. Starting early 6 This approach may seem excellent if you know exactly what you will study or do, have a truly intercultural topic, and have designed a plan that fits the demands of your time and the limits of the program. It also may serve you if you do not change your mind about any of these elements as you move through the program. However, most students tend to grow and change in the program and discover new and interesting aspects of intercultural relations during their studies. As result of this growth, new topics are often of greater interest and plans change. Solving the problems of the world One of the basic truths about a master’s thesis or project is that it will probably not be the greatest work you do in your life. It may be a significant contribution to a small area of intercultural relations, but the whole point of a thesis or project is to train you to use a certain set of skills. A thesis focuses on the skills of academic research, analysis, and writing that you can then use elsewhere to study and report on subjects that deeply interest you. A project focuses on the skills involved in applying theory in practical ways that emphasize design, implementation, and assessment of outcomes. So you will need to select a topic that is manageable and not unrealistically ambitious. Your advisor will help you here. Thinking you should know, but not knowing and feeling lost If you find yourself feeling lost, remember our opening advice: DON’T PANIC! One of the purposes of the nine core courses in the program is to involve you in various aspects of intercultural relations, so you can begin to sense which aspects of the field attract you most. The Research II course will help you learn the conventions of narrowing a topic and designing a workable research question. Many of the assignments throughout the program will help you think about applying your learning in ways appropriate for the capstone project. And, finally, you will have a variety of faculty and advisors, as well as the pragmatic realities of the world around you, to help limit your possibilities. It won’t be, and shouldn’t be, perfect You will often hear that there are two kinds of theses or capstone projects: a perfect one and a finished one. What this means is that there are realistically speaking, no “perfect” masters’ theses or projects. The thesis is a practical, working form of technical writing, designed to communicate academic research to a limited audience of other academics. The project is very practical in nature, also, showing your ability to design, implement, and assess some real world effort. High standards and ethics are very important in your master’s work, but that does not translate as a demand for perfection. Selecting a Thesis or Capstone Project Topic 7 Sometime after the second or during the third intensive session of classes, you will want to begin considering your thesis or capstone project topic. You will want to begin considering if your emphasis will be on research (to do a thesis) or on practice (to do a capstone project). Two of the courses—Advanced Intercultural Communication Theory and Research II—are specifically designed to help you begin to focus your interests and to practice designing, carrying out, and writing up social science research. Other courses and assignments will help you think about how to take your learning and use it in practice for the capstone project. Any time during the program, however, you may discover an interesting thesis or capstone project topic. It is a good idea to have a special notebook or folder in which you write down ideas that come to you, e.g., subjects or people you would like to learn more about, kinds of research that appeal to you, and skills or practices you would like to teach others in order to improve intercultural relations. (One faculty member calls her folder “Half-Baked Ideas.”) As you let these ideas take shape in the back of your mind, you can begin to sort through them by asking yourself questions like these: What areas draw my attention? As you take courses or read for other purposes, what ideas, subjects, types of research, kinds of practical applications consistently attract your interest? What concerns you most in your reading, at work, or in your community that might be a subject for social science research or practice? What do I hope to do in the future? In particular, consider what professional directions seem most useful and most likely for you. What areas of specialization would you like to develop? What knowledge will prepare you for the next step in your place of work or help you move into new work? What research might benefit you in the future? What demonstration of theory into practice would serve you well professionally? What authors, studies, research, or projects really excite me? This question can be the most useful and the most dangerous in helping you decide on a thesis or project topic. A truly exciting topic can carry you through the many hours of reading, thinking, designing, implementing, and writing that may be necessary to create a finished thesis or capstone project. On the other hand, caring too much about the subject can tempt you to take on too much. As you slowly explore possibilities for your thesis or project, you will eventually begin to narrow your options and, ultimately, to settle on a single topic. There are many rather pragmatic considerations that help people determine which thesis or project topic they will choose. Some of the considerations that can help focus your interests include the following sections on doing a thesis or undertaking a capstone project. Preparing To Do A Thesis 8 If you are thinking about doing a thesis, the following section should help you as you travel from thesis topic to a completed thesis proposal and ultimately to a finished thesis. Let us begin now with questions regarding doing a thesis: What type of research do I want to do? Interviews, focus groups, written surveys? A document study or a field study? A traditional research study or a theoretical analysis or a project that combines research with practice? Do I have the resources to carry out the study I envision? Are people available as potential research participants, and are they available when I need them? How long will the study take, realistically, and can I clear that amount of time when I need it? (One semester is about the minimum.) Does my possible research topic fit with my professional/educational/personal goals? In this program, students often use the Research II course as a place to practice the skill of focusing on a research topic, including the crucial step of converting an idea for thesis research into what social scientists call the research question or research problem. MAIR Thesis Committee Your thesis committee is composed of three people: 1. Thesis advisor 2. Chair 3. Member The thesis committee should be selected when you are beginning to get clear vision about the focus of your thesis so that you can receive advice as you move toward the precise selection of your topic. Together, your advisor, committee chair, and committee member should display the expertise needed to guide you through your thesis. Please note that two of the three-committee members must have doctorates, while the third may have a master’s degree. Thesis Adviser The thesis adviser is typically the students’ academic faculty adviser. This person will work closely with the student to make sure that all of the University of the Pacific protocols (IRB, proposal review, final thesis review, etc.) are followed. This person may not have expertise in your exact area of research, but will be well grounded in the overall 9 curriculum of the MAIR program and research in general. The thesis advisor is typically the primary advisor on your thesis. Thesis Committee Chair The committee chair typically works in tandem with the thesis advisor to provide the primary direction for the thesis in terms of topic and method. The chair works with you through the selection of a topic, to the choice of research method, to the form of analysis employed. The chair should clearly have the expertise appropriate for the area of study of your thesis. Working closely with the thesis committee member and the thesis advisor, the chair will help to see that the thesis meets the standards and requirements of the field in general and MAIR specifically. Thesis Committee Member The thesis committee member is typically the secondary advisor on your thesis. The member should clearly have the expertise or special interest appropriate for the area of study of your thesis, and should balance the attributes of the chair. Under the following section on “Tips for Selecting your Thesis Committee,” there is a list of both necessary and helpful characteristics. Special Note: While there are general patterns typical of thesis committee membership and roles, those patterns and roles may vary greatly depending on the committee. For example, it is possible that the committee will work very closely together and will decide to review all parts of your thesis at the same time. In other cases, you might work extensively with the chair or your thesis advisor, prior to requesting feedback from others. Each committee will establish its own way of operating in order to meet your needs, while recognizing their individual methods of operation. To serve on the thesis committee, prospective members must offer 3 ‘yeses’ to the students: 1. Yes I will sit on the committee. 2. Yes, I will read the proposal, provide feedback and ultimately approve so that this research will move forward. 3. Yes, I will read the full thesis, provide feedback, and finally approve the thesis for graduation. Tips for Selecting a Thesis Committee At some point in thinking about your thesis, you and your faculty/thesis advisor will start to discuss possible committee members. There is no specific time for this to happen, but you want to do it early enough so the committee chair and member both have a chance to have input on your thesis topic and research strategy. While you might talk with 10 candidates yourself, sometimes your faculty advisor will make the first contact. Everything depends on who you are considering and the relationships that person has with you and with MAIR/ICI/Pacific. When you are trying to select your thesis committee chair and member, remember there are several factors to take into consideration. The following attributes all need to be represented on your thesis committee: • academic expertise in your main area of focus • professional experience in your main area of focus • experience in thesis advising • connections into professional networks • time to spend working with you • an interest in your topic • an enthusiasm for facilitating your professional development • familiarity with current literature in your area of focus • a Ph.D. or other terminal degree BALANCE is the key to a successful committee experience. Use the above list to check carefully that the essentials are present in one or both members. Other attributes that might prove helpful include: • willingness to allow you to assist them in some aspect of their work • willingness to share articles or books with you that could prove helpful • willingness to mentor you These attributes are certainly not essential, but are often happy accidents of your involvement with the program. These “happy accidents” occur because you have skills, talents, or time to offer, or because you are working on a topic that is particularly salient to the committee member. It is often best not to request such support in your initial contact but to allow some time for the working relationship to develop. Questions to Ask Your Thesis Committee Members Once you have secured your thesis committee members, you will want to establish a pattern of communication with each of them to keep them informed of your progress. When your thesis committee chair and member are appointed, they will receive faculty guides to doing the thesis, which will include materials from this handbook. This will help them to work with you as you begin to develop ideas for your thesis. As soon as they have agreed to work with you, however, there are some important questions for you to ask them: 11 1. What is the best way for you to maintain contact with them: Phone appointments Email Face-to-face meetings SKYPE Fax 2. Would they like to see copies of your other work before working with you on your thesis? 3. In what form do they want to see your work: Email Fax Mail 4. Would they like to receive your thesis chapter by chapter or in larger sections? We suggest that you avoid having committee members wait to read the entire thesis. Experience has shown that most students need feedback earlier in the process. Finally, however, whatever strategy is chosen, it should be one that works for you and your committee members. 5. Are there any other things that it would be helpful for you to know about the committee members’ ways of helping a student undertake a thesis? Moving from a Thesis Topic to a Research Question The first and most important task in moving from a thesis topic to a research question, or research problem statement, is to narrow your subject. You may, as many students have, approach the thesis with a very large and unwieldy topic and you must learn to limit the scope, pare away unneeded elements, and hone a clear, manageable research question. The research question will then guide your reading for the literature review, point you to the most appropriate research methods for answering the question for your thesis, and shape your analysis of the data that surface as you explore the question. But the process of turning a general thesis topic into a question that can guide the rest of your thesis process is an art, not a science. Some tactics that might help you move from thinking about your general topic to framing a specific question for your thesis include: Searching the literature. This task involves scanning the literature to gain an overall sense of the types of research being done related to the ideas that you have. You will also do some in-depth reading as find research that interests you most. During this examination of the literature, you are looking for articles and books that will provide you with examples of other research questions, so you will have a 12 sense of what has already been done in the area. When reading articles, especially, look at conclusions about what research still needs to be done in the topic area you are examining. The literature you search will also generate a preliminary list of books, articles, and other resources you will need when you begin your literature review for the thesis. The research studies you read may: help you define and clarify your research question(s) help you understand how to carry out the kind of research you hope to do serve as a model for style and format later as you write your thesis Remember to make clear citations of everything you read. You will probably want that information again! Reviewing other theses. It is important to take the time to review a thesis completed by a graduate of the program. As you go through the program, you need to review other samples, especially when you get ready to select your topic and create a research question. By reviewing other theses you will begin to get a sense of the process of moving from an overall issue or problem to a more specific research question. Talking with advisors. Talking extensively with your faculty/thesis advisor will be critical as you define your general topic and then your narrowed research question. This will be important also in the selection of people to serve on your committee. You can discuss your thesis research with your faculty advisor throughout the program and with your thesis committee as it takes shape. During the third residency you need to have in-depth conversations about what research problems are appropriate and doable to assure you are on the right track. Your research question may be developed before you begin your thesis proposal, but it often will become more clearly defined during the process of preparing your thesis proposal. Regardless of the timing, the next step after selecting a topic and defining your research question is to develop a thesis proposal. Developing Your Thesis Proposal Your thesis proposal is a critical step in producing your thesis. Here you have the opportunity to explain your research question and the rationale for your study, what literature you intend to review, what research methods you propose using, who the subjects might be, how you will select them, and how you plan to analyze your findings. Preparing the Literature Review 13 Although you may have searched through some of the literature in your areas of interest before, this time as you examine the literature, you will be creating a comprehensive description of the type of books, articles, etc. that you plan on reading in greater depth for the thesis. Your goal will be to present some of the literature and identify other specific authors and their works you plan on reviewing in the thesis. You will present the focus of the literature you intend to read and explain why you have made those selections. At this point your goal may be to survey all the most relevant articles, books, and other material connected to your research subject; this is called an exhaustive review. In some cases you will be focusing on the identification of the best and most relevant literature, not all of the literature; this is called an exemplary review. It is very likely that you will have sections that are exhaustive and sections that are exemplary by the time you finish. Selecting Your Research Methods After clarifying your research question(s) and beginning a literature review, you are well underway on the first two important steps in developing your thesis proposal. Now your next task is to select research methods. Your research question and your review of some important works will provide you with critical direction in identifying possible research methods. A review of former studies will give you ideas as to what methods have been useful and appropriate in the past for addressing similar questions. Remember that your goal is to choose methods that are appropriate for your research question, your time restrictions, and your target population. You should not pick a method just because you like it, but because it works well in addressing your research question. You will often need to support your choice of methods by a brief literature review that explains and argues for the validity of your proposed methods. Making Your Project Intercultural The term intercultural refers to interaction between people from different cultures. It can, however, also be viewed in such a way as to include the interaction of elements of one culture with people from another culture. For example, one student examined how a Western evaluation method was being used and reacted to within Japanese culture. However, no matter what the final subject, make sure it involves some sense of interaction or the results of interactions between two or more cultures. It also helps if you remember the distinction between cross-cultural and intercultural research. Both types of research can be very informative to the interculturalist, but we want you to do intercultural research. If you find that you are comparing a certain behavior or attitude in one culture with another one, you are probably moving into the cross-cultural arena, which is not what you want to do. If, however, you then use that knowledge to create a training program, a class, book, etc., that helps cultures to improve intercultural relations, then you are doing appropriate intercultural work. Or, if you are comparing the long-term 14 effects of international assignments on employees from two different cultures, you are still in the intercultural realm. You are combining a cross-cultural and an intercultural lens in your research. You will want to consult with your advisor to make sure you have selected an intercultural focus for your research. Presenting Your Thesis Proposal This document will form the foundation for your final thesis; it also provides the core material that will be needed if and when you are submitting your proposal to the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Between the initial design of your thesis and the final implementation, many things may change, but the original proposal should guide you through your thesis. To help you develop your proposal, you may want to follow the basic format for a research prospectus described in Rubin et al., pp. 239-242 of the 5th edition. You don’t need to answer all the questions presented in the prospectus, but you should address all that are relevant to your thesis. The content described below follows the guidelines in Research II and Pacific’s Thesis and Dissertation Guide: The Content of the Thesis Proposal Cover Page (see University of the Pacific Thesis and Dissertation Guide, which is available in the following URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Academics/Schools-andColleges/Office-of-Research-and-Graduate-Studies/Graduate-Programs/FormsResources-and-Services/Forms.html) Abstract Summarize your proposal in one to two paragraphs. Write this when you have finished the rest of the thesis proposal. Chapter 1: Introduction In this important chapter, you explain the background of your interest in the subject. You need to let readers understand how the research question or questions have developed. You will likely present some former research to set the context of your research question. Next you present the research questions in a clear and concise way. If there are terms that need clarification, this is also often where you provide those definitions. (Note that definitions may also go into an appendix or simply be presented in the context of the paper, so you should discuss options with your advisors.) At the end of this section, provide a very brief introduction to each of the subsequent chapters in the thesis. Chapter 2: Review of Literature 15 The goal in this section in a proposal is to indicate what you plan to include in the literature review in your thesis. Provide details of a few specific works you have found that you know will be useful and say why they are relevant to your topic. Then list any additional pieces of literature you plan to explore, provide the specific authors and their works, and identify why their work seems useful to you. In summary, for the proposal, you will give an overview of your initial survey of the literature; you will identify in some detail a few of the pieces you will be reading; and you will indicate the other authors and works you intend to read and again explain why you are reading them. In this process, you will identify the relevant research and/or theoretical frameworks you intend to use and mention any complementary or competing frameworks for your thesis. Chapter 3: Method If you are using human subjects, you will need to explain who your participants will be and how you plan on selecting them (sampling method). Explain the methods you plan on using for your research and explain why you are using these specific methods (interviewing, surveying, focus groups, document analysis, etc.). Often you will support your use of methods with literature about those methods. When you get to this point, you should begin to draft your Pacific Human Subjects Activity Review Form for approval by the University’s IRB (Institutional Review Board). Your proposal will be critical in completing this form. Any research involving human subjects requires that you gain approval from the IRB. For more information, talk with your faculty/thesis advisor. The Method’s chapter concludes by answering the essential question regarding how you will approach the analysis of your findings/results. Explain how you will present the data and then what methods and theoretical frameworks you will use for analysis. This section begins to outline what is typically in Chapter 4: Results or Findings, and Chapter 5: Discussion and Conclusions. Concluding Information The final section of the thesis proposal will include: 1. a draft table of contents of the thesis 2. a list of references (from your literature review and methods section) 3. a copy of the research tool if appropriate (e.g., interview questions or survey questionnaire) 4. a timeline for completing the thesis SPECIAL INFORMATION 16 1. Use of Human Subjects: Most research for theses involves the use of human subjects. If this describes your research, you will need to gain approval of your research from the University of the Pacific’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Therefore, once you have completed the proposal and submitted it to your thesis committee chair, member, and faculty/thesis advisor for approval, you will need to submit your human subjects review form, which is built upon your proposal, to the MAIR Academic Director and to the IRB for final approval. Work with your thesis advisor to complete this task well before starting on your research. Remember the IRB approval process applies only if you are using human subjects. 2. Use of the University of the Pacific Library online: If you haven’t learned to use the University of the Pacific’s library resources available to you at a distance, now is the time to learn. It will be critical for you to know how to use the library as you undertake your thesis proposal and thesis. Again, contact Katrina Jaggears for the most current information on how to use the library and what assistance may be available 3. Use of APA and Pacific Style: For the thesis proposal, as well as your thesis, you will be using current APA style, but you will also be using style guidelines presented in the University of the Pacific Thesis and Dissertation Guide, which is available at the following URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Academics/Schools-and-Colleges/Office-ofResearch-and-Graduate-Studies/Graduate-Programs/Forms-Resources-andServices/Forms.html. 4. Use of an Editor: It is advisable to find an editor or knowledgeable friend or colleague to assist you in applying these style directions as you complete your thesis. You may also need such assistance with your writing. You should never turn in a draft of your proposal or thesis without it having been edited first. The University of the Pacific’s writing resources may help along the way. Please contact Katrina Jaggears for information on how to access their resources. 17 PREPARING TO DO A CAPSTONE PROJECT Many of the principles behind doing a capstone project are similar to those involved in doing a thesis, but have a somewhat different emphasis. The first task for you to undertake is to consider the following issues: What type of capstone project do I want to do? Will it concern training, teaching, materials development, program design, or a creative effort? What theoretical frames might help guide the project? Do I have the resources to carry out the capstone project I envision? If I need people to carry out my project, are they available to participate, and are they available when I need them? How long will each step take, realistically, and can I clear that amount of time when I need it? (One semester is about the minimum) Does my topic for the capstone project fit with my professional/educational/ personal goals? In this program, most students examine issues of application in their course assignments and electives, and often their place of work provides a stimulating environment for thinking about the movement of theory into practice. It is often the case that practical problems, issues, and needs identified in the work environment will lead to projects designed to cope with those situations. This typically creates a rich playing field in which to build a project and provides a clear motivation for carrying out the capstone project. MAIR Capstone Project Committee Your capstone project committee is composed of two people: 1. Faculty/Project advisor 2. Area Specialist The capstone project committee should be selected when you are beginning to get clear vision about the focus of your project so that you can receive advice as you move toward the precise selection of the project you will undertake. Together, your faculty/project advisor and your area specialist should display the expertise needed to guide you through your project. Please note that one of the two-committee members must have a doctorate. Project Adviser The project adviser is typically the student's academic faculty adviser. This person will work closely with the student to make sure that all of the University of the Pacific 18 capstone project protocols are followed. This person may not have expertise in your exact area of the project, but will be well grounded in the overall curriculum of the MAIR program and application of theory in general. The project advisor is typically the primary advisor on your capstone project. Area Specialist The area specialist will work in collaboration with the project advisor to provide the foundation of theory and practice needed for the success of the project. The specialist should clearly have the expertise and experience appropriate for the nature of your capstone project. This person will assist with the selection of the focus of the project, the literature needed to support the effort, and the resources integral to carrying it out. Ultimately, the area specialist and the project advisor work closely to assure that the capstone project meets the standards and requirements of a practice-oriented project in the field in general and MAIR specifically. Special Note: While there are general patterns for typical advisors and area specialists, the roles may vary greatly depending on the individuals involved. For example, it is possible that the area specialist might work very closely with the student as a result of a previous educational or professional connection. In other cases, the main work might be done with the project advisor, and the area specialist would focus more on assessment of the success of the various stages of the project. To serve students doing capstone projects, a prospective area specialist, must offer 3 ‘yeses’ to the students: Yes I will serve as the area specialist on your capstone project committee Yes, I will read your proposal, provide feedback and ultimately approve so that this project will move forward Yes, I will read the final analysis, provide feedback, and give final approval of the capstone project for graduation Tips for Selecting an Area Specialist At some point in thinking about your capstone project, you and your faculty/project advisor will start to discuss possible area specialists. There is no specific time for this to happen, but you want to do it early enough so the faculty/project advisor and area specialist may both have a chance to have input your capstone project. While you might talk with candidates yourself, sometimes your faculty/project advisor will make the first contact. Everything depends on who you are considering and the relationships that person has with you and with MAIR/ICI/Pacific. When you are trying to select your area specialist, remember there are several factors to take into consideration. The following attributes all need to be represented between your 19 faculty/project advisor and your area specialist: • academic expertise in the area of your project • professional experience in your main area of focus • experience in advising practical projects grounded in theory • connections into professional networks • time to spend working with you • an interest in your project • an enthusiasm for facilitating your professional development • familiarity with current literature in support of your project area • a Ph.D. or other terminal degree BALANCE is the key to a successful advising experience. Use the above list to check carefully that the essentials are present in one or both members. Other attributes that might prove helpful include: • willingness to allow you to assist them in some aspect of their work • willingness to share articles or books with you that could prove helpful • willingness to mentor you These attributes are certainly not essential, but are often happy accidents of your involvement with the program. These “happy accidents” occur because you have skills, talents, or time to offer, or because you are working on a topic that is particularly salient to the area specialist. It is often best not to request such support in your initial contact but to allow some time for the working relationship to develop. Questions to Ask Your Area Specialist Once you have secured your area specialist, you will want to establish a pattern of communication to keep the person informed of your progress. When the area specialists are appointed, they receive information about their role on the committee and the nature of a capstone project for the program. This will help them to work with you as you begin to develop ideas for your project. As soon as they have agreed to work with you, however, there are some important questions for you to ask them. 1. What is the best way for you to maintain contact with them: Phone appointments Email Face-to-face meetings SKYPE 20 Fax 2. Would they like to see copies of your other work before working with you on your capstone project? 3. In what form do they want to see your work: a. Email b. Fax c. Mail 4. Would they like to receive your final report chapter by chapter or in larger sections? We suggest that you avoid having the area specialist wait to read the entire final paper. Experience has shown that most students need feedback earlier in the process. Finally, however, whatever strategy is chosen, it should be one that works for you and both your faculty/project advisor and your area specialist. 5. Are there any other things that it would be helpful for you to know about the area specialists’ ways of helping a student undertake a project? Moving from a Capstone Project Topic to a Specific Proposal The first and most important task in moving from a capstone project topic to a specific proposal is to clarify your goals and objectives and lay out what you plan on doing. You may find yourself wanting to do a project that is too large or, in some cases, too small. It will be critical for you to set up the parameters of your project early so that the scope of your efforts will be clear and the final project manageable. These goals and objectives will then guide you in the planning and design process, which is your next task. Once you have identified these elements, it will be time to examine the literature relevant to your project. As with the thesis, you need to gain an understanding of how your capstone project fits within the literature of the field. In this case, it is important to identify research and practical applications related to your focus. You will examine the literature that will help guide you in the development of your capstone project. The literature review is designed to provide the theoretical and research context for the design of your capstone project as well as its ultimate analysis. Searching the literature. This search involves the careful scanning of materials that will provide insight and guidance for the project you plan on undertaking. In addition, it will include the theoretical framework that supports the goals and objectives underlying your application of theory to practice. During this examination of the literature, you are looking for articles and books that will provide you with discussions, examples, theoretical frameworks, or research related to the practical effort you will be pursuing. 21 The literature search will generate a preliminary list of books, articles, and other resources that you will need as you design your capstone project. The literature review will: help you define and clarify your goals and objectives help you understand how to design and implement the kind of project you hope to do help you learn approaches and methods appropriate to your topic Remember to make clear bibliographical notes on everything you read. You may want that information again! Talking with advisors. Talking extensively with your faculty advisor will be critical as you delineate the elements of your capstone project and create goals and objectives for your design. During this time, you will also work with your faculty advisor to select an appropriate area specialist to serve as the second member on your capstone project committee. In some cases, depending on the project and committee, another area specialist may join the committee. During your third residency (and sometimes before), it is advisable to begin a conversation with your faculty advisor concerning your choice of a capstone project or a thesis. You will need to have in-depth dialogue about which approach is best for you and your overall goals. You want to make sure that you have selected an approach that is appropriate and doable. These conversations will help assure that you are on the right track. Surveying real world issues. If you are thinking of doing a capstone project, it is a good idea to keep a file of possible projects that occur to you as you go through your courses, analyze the needs and challenges of your workplace as well as other settings, and hear about other projects undertaken in the field. Practical projects carried out by others may stimulate ideas or serve as models for what you decide to undertake for your capstone project. Preparing Your Capstone Project Proposal Designing your project proposal is a critical step in producing your capstone project. Here you have the opportunity to explain what you plan on creating, what literature you intend to review in order to provide the context of your project, what approaches you plan on using to achieve your goals, and what theories, research approaches, models, etc. you will use to support your project and analyze its completion. Your first step is to develop a Capstone Project Proposal. Once your faculty advisor and area specialist have approved your proposal, you will complete the task of designing the Capstone Project. The proposal will provide a clear and concise description of the project’s 1. goals and objectives 22 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. ultimate outcome (the project itself) literature that provides a practical and theoretical context methods, approaches, strategies, and tasks involved in creating the project projected form of analysis of the project and related learning potential challenges in carrying out the project The proposal should be approximately 10-12 pages in length. The content of the proposal may be adapted for use in the next step, which is the creation of the capstone project design plan. Creating the Capstone Project Design Plan Once your capstone project proposal has been approved, you will complete the design of the full project plan. This document will form the foundation for your project from design through implementation to final analysis. Between the initial design of your project and the final implementation, many things may change, but the original design plan is an important step in guiding you through your capstone project. A capstone project in the MAIR program is designed to allow you to create a practical event (e.g., training or course) or materials (e.g., training manual, an intercultural book, or tool for assessment) to be used in your work (current or future). The following is a description of the various elements that will be a part of the final Capstone Project report and will be written at various times during the development of the project. Cover Page (see University of the Pacific Thesis and Dissertation Guide, which is available in the following URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Academics/Schools-andColleges/Office-of-Research-and-Graduate-Studies/Graduate-Programs/FormsResources-and-Services/Forms.html) Abstract Summarize your plan in one to two paragraphs. Write this when you have finished the rest of the capstone project design. Chapter 1: Introduction Your first task for a capstone project is to provide an overall description of what you plan on doing. This will begin with a clear statement of your project’s goals, objectives, and rationale; what you are going to do and what are the reasons you are going to do this project. Next you need to have a clear sense of the people you are designing the project for, e.g., who will take it, read it, or use it? In determining these qualities, what is the value of the project for those who you intend to serve? At the end of this chapter, you should provide a preview of the coming chapters in the capstone project design plan. 23 Chapter 2: Literature Review Although you may have searched through some of the literature in your areas of interest before, this time as you examine the literature, you will be creating the context as revealed in books, articles, etc. that provide the foundation for your project. Your goal will be to present the literature and explain why you have made those selections. You will survey relevant articles, books, and other material connected to your capstone project. You will be focusing on the best and most relevant literature related to your project, not all the literature available. Your review of the theoretical and research literature has two main goals. First, you want to provide a practical and research context for your capstone project. You will examine what relevant research has been done that will help you design, implement, and analyze the outcome of your project. In addition, your literature review will examine the content and processes core to your project in order to support the project as a whole. This portion of the literature review will also provide much of the context for analyzing the final project. The second goal is to provide the theoretical foundation for your capstone project. Regardless of the nature of your project, you will build it upon theories, research, models, etc. that arise from your intercultural studies. These elements will be especially important as you move into the final stage of the project in which you analyze the outcome from a theoretical perspective. Chapter 3: Methods to Be Employed Most capstone projects will be partially designed even before you begin the formal design process. Your employer may have a task in mind that will guide the development of the capstone project; you may have a long-term interest in creating some event or written material; or you may recognize a need in the field and seek to fill it, meeting both personal and professional goals. So, with the initial idea and potential structure in place as you move into the project design stage, one of the important steps is the selection of specific methods, approaches, or strategies that will be used to implement the project. The literature review may have provided some sense of how to proceed, but other techniques are appropriate at this time. You may want to examine other projects completed in other settings to see what was done and what the outcomes were. These reports may not always be in the literature. And you may want to interview people involved in other projects in order to learn from their successes and failures. These experiences will help you in deciding how best to approach the implementation of your project no matter what its final shape. You will need to provide a step-by-step description of the tasks involved in creating the project and its final outcome. In addition, you will describe any resources that you plan on using as part of your project. Finally, you should 24 discuss any challenges or limitations you foresee as you carry out your project so that your faculty advisor and area specialist may help you to manage these issues. Additional Information In this last section, you should include information on any tools you intend to use, resources that will be included, and any other information that will help the faculty advisor and area specialist understand your capstone project and what you need to carry it to completion. In addition, you will need to describe how you plan on reporting and analyzing the outcomes of your capstone project in Chapter 4: Project Analysis, and Chapter 5: Discussion and Conclusions. Making Your Project Intercultural As with the thesis, it is important to make sure your project is intercultural in nature. As noted earlier, the term Intercultural refers to interaction between people from different cultures. It can, however, also be viewed in such a way as to include the interaction of elements of one culture with people from another culture. For example, one student developed a tool for training American women to be more effective culturally in their work within Japanese companies. However, no matter what the final project, make sure it involves some sense of interaction between two or more cultures. It also helps if you remember the distinction between cross-cultural and intercultural research. Both types of approaches can be very informative to the interculturalist, but we want you to do an intercultural capstone project. If you find that you are contemplating a training that focuses on leadership, you will want to remember to examine leadership in diverse groups and/or leadership that crosses cultural boundaries. You could certainly train a group from South Africa about U.S. culture, but you would want to do that in a way that looks at the challenges South Africans would have in adjusting to a U.S. leader. 25 DOING YOUR THESIS In essence, you have finished the initial and critical first step in doing your thesis: you have a strong foundation in your thesis proposal on which to build. The following guide is not meant to be absolute. You may want to follow these steps, but understand that you can move around amongst the tasks if that works best for you. Often the research itself and the writing may be happening at the same time. Or the research might happen before you do much more of the writing. The list presented here, however, is a good starting point for your efforts regardless of the order you end up following. An Important Reminder. At this point, you should be following the guidelines available in the University of the Pacific’s Thesis and Dissertation Guide available at the following URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Academics/Schools-and-Colleges/Office-of-Research-andGraduate-Studies/Graduate-Programs/Forms-Resources-and-Services/Forms.html. This guide along with the APA Manual are critical to doing a good job on your thesis. Most of your question about style will be addressed in these two documents. Working off the proposal, your next steps are to: 1. Develop a draft of your table of contents and your references. Both documents will change as you go along, but they will provide a beginning sense of structure as you move forward. 2. Write a draft of your first chapter, Introduction. Building on the equivalent section in the proposal should make this task a relatively easy one. Look at what you have written and make changes that reflect what is starting to happen as you set up your research. Is the rationale for your research clear? Examine your research questions again to see that they still provide the direction you want for your study; revise them as needed. Notice how things may have changed already even though you may have just finished your proposal. 3. Write a draft of your literature review. As with the first chapter, you are starting to flesh out the details of the material you have already presented in the proposal. Now you are reviewing those articles, chapters, monographs, books, webpages, etc., you suggested in the proposal and determining if they belong in the literature review. You are looking at the logic of the organization of material and making sure it will be clear to your readers. Are there topics that you need to add? Are there topics that should be dropped? Have you discovered new research that is core to what you are studying? Remember that this chapter is written in the past tense or in the present perfect (see APA for more details). 4. Structure and organize your research. Many of the tasks connected to this activity may be done at the same time that you are reading in the literature and drafting your first two chapters. 26 5. Identify and select your participants. Make sure that you are using an accepted sampling method and that you have access to the group you wish to learn about. 6. Pretest your questions. If you are doing interviews, focus groups, or surveys, you will want to pretest the questions you have developed to make sure that you are getting the type of answers you need for your research. 7. Gain advice. Have conversations with your thesis advisor and committee to make sure you are moving along well. 8. Do your research. Make arrangements to carry out your research and collect your data. Once you are prepared to carry out your research and have received approval from your committee and the IRB, it is time to follow thorough on your plans. Rarely will things work exactly as you planned, but you need to be prepared for surprises—some challenging and some happy. Your committee can be valuable as a resource to help you if things don’t work out as anticipated. Especially keep in touch with your thesis advisor to deal with any problems that may occur. But this is also a time to enjoy yourself, to learn what you hoped to learn, to discover answers you expected and those you didn’t expect. If you find something isn’t working, start quickly to see how you might make it work; get advice, be creative. And when all is going smoothly, relax and have fun. 9. Write a draft of your third chapter called Method. As you are collecting your data, it is often time to write your third chapter as well. All of your thoughts about method have been integrated into your thinking and planning. You may have chosen to take notes on your methods section both as you were planning your research and as you were doing it. Those notes would come in handy now that you are writing the third chapter on method. Remember that you will be writing this chapter in the past tense because you have finished much if not all of the processes involved in the method by the time you are writing this chapter. In the proposal you told us what you planned on doing and now that you are essentially finished collecting data, you will need to tell us what you did; and what you ended up doing may be somewhat different from what you thought you would do originally. 10. Write your findings chapter. In a straightforward manner, you will present the information you learned from your research. There will always be a number of ways to present your results, so you need to experiment to see what way or ways will work best. For example, you could present findings according to the questions you asked or provide individual profiles for each of your participants if a small enough research project. You might present individual profiles, but then follow up with aggregate data in which you report the findings for the group. 27 11. Some of the approaches presented in the Analysis section below could be applied to presenting the findings. Or you might be reporting the results of a specific instrument such as the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale or the Intercultural Development Inventory. 12. Analyze your findings. As you begin to analyze your results, you have a number of decisions to carry out. You will have proposed making transcripts of your interviews or focus groups and that will have to be completed. Will you also listen to tapes, if you made them? Once your data are in shape for analysis, you begin to see what you have in front of you and this is likely to take time. You may feel somewhat blocked at this point, but do not fear, it will come together very soon. Here are some approaches for you to use: a. Look for themes and patterns in the data. Start to examine ways in which you might code your findings. b. Revisit your research questions and see how well your findings are addressing what you wanted to ask originally. c. Using a theory(s) or model(s), examine the data to see the connection between your findings and the constructs of different theories and/or models. For example how would the comments made by your participants be rated against the DMIS? d. You will often talk with your thesis committee to help you determine the depth and scope of your analysis. You may also find it helpful to talk with others who have insight into your research. e. At some point, it is important to remember to live with the data and ask new questions about what you discovered. Often called mining the data, you need to keep looking at your findings to see what else they might tell you. Even if you weren’t asking questions about age or gender, were there differences if you looked at those variables? Are there relationships between the answers to questions you didn’t anticipate that might be worth examining? And finally, at some point, you have to decide that you are essentially through with your analysis and write up your results. Please note that the analysis section is typically in the fifth and final chapter, however, there may be times when some analysis is included in the reporting of the findings. You have options, but it always depends on what works best for the reader. 13. Write up your fifth chapter, discussion and conclusions. This chapter will include: 28 a. your general analysis of what you learned from the research, b. what was most the important part of what you learned, c. the connections between your findings and the literature you reviewed, conclusions you have drawn, d. limitations to your study (what would you do differently next time), applications of the results of your study, and e. questions for further investigation on your research topic as a result of your study. One of the major steps will be to look at your results in light of the literature you reviewed. Are they in harmony or do they contradict each other? Do your findings build on prior research? If you discover the need to bring in new literature to help your analysis, that is fine and you may include it. However, you also must return to the literature review and add that new literature there as well. Getting ongoing advice. As has been noted before, you need to maintain consistent contact with your thesis advisor and thesis committee throughout this time. You will work with them to determine when they want to read your work and how much they want to read at a time. You need to recognize that they are also busy people and may not have time to read your thesis as fast as you would desire, but it is always appropriate to ask for an estimate as to when a section of your thesis will be ready to return to you. Editing and some new writing. While you are conducting your research and writing your thesis, there will be days when you don’t feel especially creative or stimulated to write much. You can still make progress on those days. You might choose to carefully edit your reference list or you might develop the introductory pages of the thesis, including your table of contents and any other tables you need to develop. You can double check all of your quotations to make sure they are accurate. Remember that good writing is good editing, so taking time to edit yourself will save time in the long run. Preparing to turn in your thesis. As you are writing your last chapter or editing your thesis, it will be time to prepare for other aspects of completing your thesis: Preliminary pages and Signature page. You may want to develop your preliminary pages from the beginning, but if you haven’t done so, now is the time to develop those pages. The instructions and examples in the Pacific Thesis and Dissertation Guide are clear and easy to follow. Thesis checklist. When your thesis has been approved by all of your committee members, it will be time to submit your thesis to the University of the Pacific Office of Graduate Studies and Research. In addition to the thesis itself and the signature pages, you also need to turn in the thesis checklist found at the URL below. You will fill it out, check that you have dealt with all of the requirements, and forward it to your thesis advisor for signature. The URL is: http://www.pacific.edu/Academics/Schools-and-Colleges/Office-of-Research- 29 and-Graduate-Studies/Graduate-Programs/Forms-Resources-andServices/Forms.html What next? Certain things are critical at this point: Following deadlines. You must follow all of the deadlines in order to graduate when you want to. Pay fees on time. When you turn in your thesis for its first review, you need to make sure that you have also included your relevant payment. Please contact your faculty advisor if you have any questions about any aspect of this guide or the other materials designed to help you complete your capstone project. Kent Warren: kwarren@intercultural.org Chris Cartwright: ccartwright@intercultural.org Janet Bennett: jbennett@intercultural.org 30 DOING YOUR CAPSTONE PROJECT As with the thesis, by the time you start carrying your capstone project, you have already made important progress toward its completion. The creation of the capstone project proposal is vital to undertaking the implementation and analysis stages. It is important to remember that this specific guide as with the thesis guide is not meant to be a regimented system for undertaking your capstone project. Instead it is to be seen as a description of the various tasks that need to be taken into consideration as you move forward in undertaking a capstone project. At the same time, however, the project may work most effectively after you have completed certain crucial steps. The Role of the Project Proposal. In the case of a capstone project, your project proposal becomes an incredibly vital step in writing the first chapters in your final document. The proposal provides the critical elements that form the foundation of the first two to three chapters of your final project paper: the statement of goals and objectives as well as a basic rationale for the project, the literature review, and a statement of methods. It is also common for the capstone project proposal to serve as the direct step into the implementation of the project. An Important Reminder. At this point, even though you are doing a capstone project, you should be following the guidelines available in the University of the Pacific’s Thesis and Dissertation Guide available at the following URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Academics/Schools-and-Colleges/Office-of-Research-andGraduate-Studies/Graduate-Programs/Forms-Resources-and-Services/Forms.html. This guide along with the APA Manual are critical to doing a good job on your capstone project. Most of your question about style will be addressed in these two documents. Steps for moving forward on your capstone project: The following list of steps, while similar to the thesis steps, has important differences that reflect a focus on implementation and on the practical nature of the project. Again, we have a good starting point, but the precise order you follow is flexible and varies according to your needs and available resources. Based on the project proposal, your next steps are to: 1. Develop a draft of your table of contents and your references. As with the thesis, initial organization is important. Establishing the potential structure of the project paper provides a sense of the whole and as well as the logic guiding the entire effort. 2. Prepare a draft of the first chapter, Introduction. Laying out the basics of the capstone project is very important as you work on setting up the project itself. To begin, the presentation of the goals and objectives of the project is a vital element in clarifying what you are going to do and what the rationale is for those efforts. 31 3. Finalize your literature review (your second chapter). The literature review in the proposal may not be as long or inclusive as one for a thesis proposal, but it will often be more complete and thorough as it presents a focused literature review in support of the project. The project proposal for a thesis typically identifies examples and suggestions as to what will be examined and reviewed. For a capstone project, however, the literature review in the proposal will present an almost complete review of relevant literature. You will want to double check various databases, online resources, etc. to make sure that you have selected the works that best support the efforts you are about to undertake to complete your capstone project. 4. Structure and organize your project. Whatever you are planning to do for your capstone project, you will need to provide a clear and detailed plan for undertaking the project. This effort will have begun while writing the project proposal, but the final structure and organization will be dependent upon what starts to happen as you carry out the tasks of the project. While you will have developed a sound plan of action, each step may affect what follows and changes are inevitable. The overall structure and organization will provide the logic that undergirds the project and allows changes to take place without upsetting the overall implementation activities. Your project advisor and area specialist will be critical in offering ideas and directions that will make movement through the project easier and smoother. 5. Carry out your project. No matter what you have selected to do, it is apt to change in some way while you implement it. But with your plan in hand, you are prepared to handle what comes your way. To maximize the learning achieved during the implementation state, it is important that you keep records of what you are doing and learning. This is often accomplished best by your keeping a journal throughout the design and implementation stage. Whether this is a daily, biweekly, or weekly event, it is crucial that you maintain reflections of your learning throughout the implementation stage. These comments will help you greatly when you move on to the last stage of the project and analyze what worked, what didn’t work, what needs to be done differently, and what you learned overall. As with the thesis, this is also an important time to enjoy yourself. You have the opportunity to test your knowledge and skill in a practical setting, to determine how well your perspectives translate into useable products, and to create a union of theory into practice. The learning you achieve in the capstone project can also help guide you as you make professional decisions in the future. 6. Write a draft of your third chapter called Method. Much of this chapter already exists in your proposal and in the notes, materials, and writing you did in the process of structuring and organizing the project. While parts of this chapter have been written as part of future planning, the final version is completed after the capstone project has been finished so that you can describe what actually 32 ended up happening in addition to what was planned, which will undoubtedly be different. The method chapter is also strongly connected to the appendices, since materials ancillary to the project are often referred to in this chapter. This chapter needs to be very clear as it provides the core description of what was done in the project. The analysis that follows as well as the discussion and conclusions at the end will be critically tied to what was presented in this chapter 7. Write your analysis chapter (4th). Pulling from your journals and other reflections from throughout the preparation of the capstone project, you will now analyze what happened in the creation and implementation of your capstone project. In addition, you will examine all that occurred from the theoretical frameworks used to create the project in the beginning. You will need to go back to the original goals and objectives of the project to determine how well you have done in achieving what you originally intended. In many cases, you will also have received evaluations of your capstone project, which then will form another portion of your analysis of the project. 8. Write up your fifth chapter, discussion and conclusions. This chapter will focus on what you learned by doing the capstone project, what conclusions you have drawn, what limitations you now find in what you have done, and a statement as to what you would do differently if done again. Building on what you have learned this chapter also provides the opportunity for you to make recommendations for other practitioners. While not being a research project, many capstone projects will present ideas for research as well as ideas for future projects or for modifications in the current capstone project. These ideas are also a critical part of this chapter. Getting ongoing advice. In order for the capstone project to develop well and for the final paper to be written well and in a timely manner, you need to maintain contact with your faculty advisor and area specialist. From the approval of the proposal on, you should establish a pattern of communication with both of these individuals to make sure that you are on track with all aspects of the project. It will also be important for you to learn when they would like to read your work, how much they would like to read at a specific time, and when they would hope to be able to respond to you. In addition, you need to know how they prefer to be contacted. Editing your writing. While you are writing your capstone project, remember that good writing is good editing. It is important to remember that you need to finish your writing and then go back for careful editing in terms of grammar, punctuation, and organization, as well as APA. On days where it is hard to write, you might select to carefully edit your reference list or you might develop the introductory pages. You might also re-examine your quotations to assure their accuracy. Always remember that each little step brings you closer to finishing the project. 33 Preparing to turn in your capstone project. As you are writing your last chapter or editing your project, it will be time to prepare for other aspects of completing your degree. You need to have applied for graduation early in the semester prior to when you plan on graduating. You also need to make sure that you have followed all deadlines and paid all relevant fees on time. Preliminary pages and Signature page. You may want to develop your preliminary pages from the beginning, but if you haven’t done so, now is the time to develop those pages. The instructions and examples in the Pacific Thesis and Dissertation Guide are clear and easy to follow. Please contact your faculty advisor if you have any questions about any aspect of this guide or the other materials designed to help you complete your capstone project. Kent Warren: kwarren@intercultural.org Chris Cartwright: ccartwright@intercultural.org Janet Bennett: jbennett@intercultural.org