Westminster-Hall-Li-Aff-Greenhill Tournament

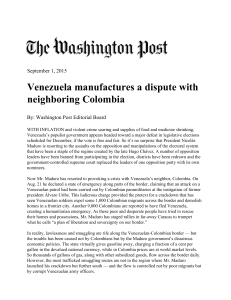

advertisement