Chapter 2 - WordPress.com

advertisement

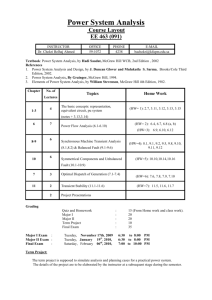

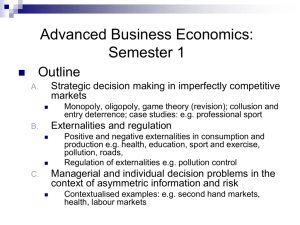

PowerPoint Presentation by Mehdi Arzandeh, University of Manitoba Market Failures: Public Goods and Externalities 4 LEARNING OBJECTIVES LO4.1 LO4.2 LO4.3 LO4.4 LO4.5 LOA4.1 Differentiate between demand-side market failures and supply-side market failures. Explain the origin of both consumer surplus and producer surplus, and explain how properly functioning markets maximize their sum, economic surplus, while optimally allocating resources. Describe free riding and public goods, and illustrate why private firms cannot normally produce public goods. Explain how positive and negative externalities cause underallocations and overallocations of resources . Show why we normally won’t want to pay what it would cost to eliminate every last bit of a negative externality such as air pollution. Describe how information failures may justify government intervention in some markets. © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-2 4.1 Market Failures in Competitive Markets • A demand-side market failure • Demand curves do not reflect consumers’ full willingness to pay for a good or service. • A supply-side market failure • Supply curves do not reflect the full cost of producing a good or service. LO1 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-3 4.2 Efficiently Functioning Markets 1. Demand curve must reflect the consumers full willingness to pay 2. Supply curve must reflect all the costs of production • The market will produce only units for which benefits are at least equal to costs. • The market will maximize the amount of benefits surpluses that are shared between consumers and producers. LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-4 4.2 Efficiently Functioning Markets Consumer Surplus • Difference between what a consumer is willing to pay for a good and what the consumer actually pays • Extra benefit from paying less than the maximum price LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-5 TABLE 4-1 (2) Maximum Price Willing to Pay (3) Actual Price (Equilibrium Price) Bob $13 $8 $5 (=$13-$8) Barb 12 8 4 (=$12-$8) Bill 11 8 3 (=$11-$8) Bart 10 8 2 (=$10-$8) Brent 9 8 1 (= $9-$8) Betty 8 8 0 (= $8-$8) (1) Person LO2 Consumer Surplus © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited (4) Consumer Surplus 4-6 FIGURE 4-1 Consumer Surplus Price (per bag) Consumer Surplus Equilibrium Price = $8 P1 D 0 Q1 Quantity (bags) LO1 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-7 4.2 Efficiently Functioning Markets Producer Surplus • Difference between the actual price a producer receives and the minimum price they would accept • Extra benefit from receiving a higher price LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-8 TABLE 4-2 (2) Minimum Acceptable Price (3) Actual Price (Equilibrium Price) Carlos $3 $8 $5 (=$8-$3) Courtney 4 8 4 (=$8-$4) Chuck 5 8 3 (=$8-$5) Cindy 6 8 2 (=$8-$6) Craig 7 8 1 (=$8-$7) Chad 8 8 0 (=$8-$8) (1) Person LO2 Producer Surplus © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited (4) Producer Surplus 4-9 FIGURE 4-2 Producer Surplus Price (per bag) Producer surplus S P1 Equilibrium price = $8 Q1 Quantity (bags) LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-10 FIGURE 4-3 Efficiency: Maximum Combined Consumer and Producer Goods Price (per bag) Consumer surplus S P1 Producer surplus D Q1 Quantity (bags) LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-11 FIGURE 4-4(a) a Efficiency Losses (or Deadweight Losses) Efficiency loss from underproduction S Price (per bag) d b e D c Q2 Q1 Quantity (bags) LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-12 FIGURE 4-4(b) a Efficiency Losses (or Deadweight Losses) S Efficiency loss from overproduction Price (per bag) f b g D c Q1 Q3 Quantity (bags) LO2 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-13 4.3 Public Goods Private goods characteristics • Produced in the market by firms • Offered for sale • Rivalry • Excludability LO3 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-14 4.3 Public Goods Public goods characteristics • Provided by government • Offered for free • Nonrivalry • Nonexcludability • Free-rider problem LO3 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-15 TABLE 4-3 Demand for a Public Good, Two Individuals (1) Quantity of Public Good (2) Adams’ Willingness to Pay (Price) 1 $4 + $5 = $9 2 3 + 4 = 7 3 2 + 3 = 5 4 1 + 2 = 3 5 0 + 1 = 1 LO3 (3) Benson’s Willingness to Pay (Price) © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited (4) Collective Willingness to Pay (Price) 4-16 FIGURE 4-5 The Optimal Amount of a Public Good Benson’s Demand $4 for 2 Items $2 for 4 Items Adams’ Demand $3 for 2 Items $1 for 4 Items P $6 5 4 3 2 1 0 P $6 5 4 3 2 1 0 D2 1 2 3 Benson 4 Q 5 D1 1 2 3 4 Q 5 Adams Collective Demand $7 for 2 Items $3 for 4 Items Connect the Dots P S $9 7 5 Collective Willingness To Pay 3 DC 1 0 1 2 3 4 Collective Demand and Supply LO3 Optimal Quantity © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 5 Q 4-17 4.3 Public Goods Cost–Benefit Analysis • Cost • Resources diverted from private good production • Private goods that will not be produced • Benefit • The extra satisfaction from the output of more public goods LO3 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-18 TABLE 4-4 (1) Plan Cost-Benefit Analysis for a National Highway Construction Project, billions of dollars (2) Total Cost of Project (3) Marginal Cost (4) Total Benefit (5) Marginal Benefit (6) Net Benefit (4) – (2) No new construction $0 A: Widen existing highways 4 $4 5 $5 1 B: New 2-lane highways 10 6 13 8 3 C: New 4-lane highways 18 8 22 10 5 D: New 6-lane highways 28 10 26 3 -2 LO3 $0 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited $0 4-19 4.3 Public Goods QUASI-PUBLIC GOODS • Could be provided through the market system • Because of positive externalities the government provides them • Examples: education, streets, libraries LO3 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-20 4.3 Public Goods THE REALLOCATION PROCESS • Government • Taxes individuals and businesses • Takes the money and spends on production of public goods LO3 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-21 4.4 Externalities A cost or benefit accruing to a third party external to the transaction • Positive externalities • Too little is produced • Demand-side market failures • Negative externalities • Too much is produced • Supply-side market failures LO4 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-22 FIGURE 4-6 P Negative Externalities and Positive Externalities Negative Externalities a P St b St y z S Positive Externalities Dt x c D D Overallocation 0 Qo Qe Underallocation Q 0 Qe (a) Negative externalities LO4 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited Qo Q (b) Positive externalities 4-23 4.4 Externalities Government Intervention • Correct negative externalities • Direct controls • Specific taxes • Correct positive externalities • Subsidies and government provision LO4 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-24 FIGURE 4-7 P Correcting for Negative Externalities Negative Externalities a b P St St a S T c 0 LO4 D D Overallocation Qo S Q Qe 0 Qo Qe Q (a) (b) Negative Externalities Correct externality with tax © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-25 FIGURE 4-8 y Correcting for Positive Externalities St z S't Dt Subsidy D Underallocation Qe Qo (a) Positive Externalities LO4 Subsidy Positive Externalities x 0 St St Dt U D 0 Qe Qo (b) Correcting via a subsidy to consumers © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited D 0 Qe Qo (c) Correcting via a subsidy to producers 4-26 TABLE 4-5 Methods for Dealing with Externalities Problem Resource allocation outcome Ways to correct Negative externalities (spillover costs) Over production of output and therefore overallocation of resources 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Private bargaining Liability rules and lawsuits Tax on producers Direct controls Market for externality rights Positive externalities (spillover benefits) Under production of output and therefore underallocation of resources 1. 2. 3. 4. Private bargaining Subsidy to consumers Subsidy to producers Government provision LO4 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-27 4.5 Society’s Optimal Amount of Externality Reduction MC, MB, AND EQUILIBRIUM QUANTITY Downsloping marginal-benefit curve, MB, for pollution reduction (diminishing marginal utility) Rising marginal-cost curve, MC, for pollution reduction (increasing opportunity costs) Optimal reduction of an externality When society’s MC and MB of reducing the externality are equal. LO5 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-28 4.5 Society’s Optimal Amount of Externality Reduction SHIFTS IN LOCATIONS OF THE CURVES • Shifts in MC (e.g. due to technology) • Shifts in MB (e.g. due to preferences) LO5 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-29 FIGURE 4-9 Society’s Marginal Benefit and Marginal Cost of Pollution Abatement (Dollars) MC Socially Optimal Amount Of Pollution Abatement MB 0 LO5 Society’s Optimal Amount of Pollution Abatement Q1 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-30 4.5 Society’s Optimal Amount of Externality Reduction Government’s Role in the Economy • Government can have a role in correcting externalities • Officials must correctly identify the existence and cause • Has to be done in the context of politics LO5 © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-31 The LAST WORD Carbon Dioxide Emissions, Cap-and-Trade, and Carbon Taxes Cap and trade • Sets a cap for the total amount of emissions • Assigns property rights to pollute • Rights can then be bought and sold Carbon tax • Raises cost of polluting • Easier to enforce © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-32 Chapter Summary LO4.1 Differences between demand-side market failure and supply-side market failures. LO4.2 Explain the origin of both consumer surplus and producer surplus, and explain how properly functioning markets maximize their sum, economic surplus, while optimally allocating resources. LO4.3 Describe free riding and public goods, and illustrate why private firms cannot normally produce public goods. LO4.4 Explain how positive and negative externalities cause underallocations and overallocations of resources. LO4.5 Show why we normally won’t want to pay what it would cost to eliminate every last bit of a negative externality such as air pollution. © 2016 McGraw‐Hill Education Limited 4-33