Understanding, Not Just Knowing and Doing

advertisement

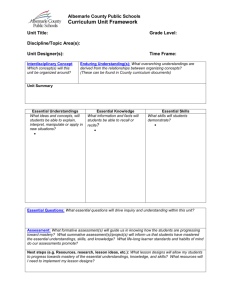

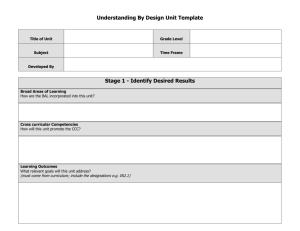

Understanding by Design: Beginning the Journey Donnell E. Gregory and Donna Herold, Presenters Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development *Who Are We? Part I: In your professional role, do you consider yourself to be primarily (1) a teacher? (2) a school-based administrator? (3) a central office administrator or supervisor? (4) a college or university representative? (5) a Board of Education member? (6) a student? (7) Other? *Who Are We? Part II: As you start this workshop, how would you rate your knowledge and comfort level with Understanding by Design (UbD): Total Newcomer: I really don’t know anything about UbD. I’m brand new to it. Beginner: I have a basic knowledge of its ideas, but I’ve never written a unit using it. Intermediate: I’ve written at least one UbD unit, but I’d like to gain more knowledge and experience with it. Advanced: I already have a lot of experience with UbD, and I’m here to fine-tune my understanding of it and to support my team, school, and/or district. *Our Agenda at a Glance Introductions and Agenda Setting What Is Understanding? (Including the Research and Learning Theory Underlying UbD and the Six Facets of Understanding) The Backward-Design Process: Why Should We Design Curriculum, Assessment, and Instruction with the “End in Mind”? Stage One: Desired Results (Including Enduring Understandings and Essential Questions) Stage Two: Assessment Evidence Stage Three: Teaching-Learning Sequence and Activities > i cdnuolt blveiee taht I cluod aulaclty uesdnatnrd waht I was rdanieg. > The phaonmneal pweor of the hmuan mnid, aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at > Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it dseno't mtaetr in waht oerdr the ltteres in a > wrod are, the olny iproamtnt tihng is taht the frsit and lsat ltteer > be in the rghit pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll > raed it whotuit a pboerlm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not > raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. Azanmig huh? > yaeh and I awlyas tghuhot slpeling was ipmorant Essential Questions for This Workshop What does it mean to understand? How does understanding differ from knowing or being able to do something? How can we support our students to understand what they are learning with depth and rigor? How can we design curriculum, assessment, instruction, and professional development to promote understanding, rather than knowledge-recall learning? How can we help all learners move from initial acquisition and integration of new knowledge and skills toward growing levels of constructed meaning and conceptual transfer? How can we maximize students’ understanding by addressing their varying readiness levels, interests, and learning profiles? Established Goals for this Institute By the end of this workshop, you should be able to: 1. 2. 3. 4. Explain the research principles and learning theory underlying Understanding by Design (UbD). Describe and facilitate six ways your students can demonstrate understanding, rather than just knowledge-recall learning. Apply the principles of backward design to your professional role(s) involving student achievement. Collaborate with your peers to develop an action plan for using UbD principles and strategies in schools, districts, and/or other learning organizations. Our Guarantee to You… By the end of this institute, you will have: 1. 2. 3. At least 10 professional development activities you can use to promote staff understanding of researchbased strategies related to teaching for understanding. A minimum of 7 handouts you can use to share key institute ideas and strategies with others. At least 7 reflective questions you can explore with other staff as part of a study group or inquiry team investigating ways to increase student understanding and achievement. As a Starting Point… THINK: What are your personal objectives for this workshop? PAIR: As a table group, determine one to two objectives that you all share. SHARE: Next, appoint a table presenter who will (1) introduce table members and (2) present your group’s objectives for the workshop. Reviewing Units That Use the Backward-Design Process (I) To understand the backward-design process, it is useful to examine actual units that make use of it. Review the examples of “before-backward design” units on pages 6-7 and 10. What is flawed or problematic about the “before” versions of “Westward Movement and Pioneer Life” and “Geometry”? Reviewing Units That Use the Backward-Design Process (II) Next, examine the “after” versions of each unit on pages 8-9 and 11. How does the “after” version of each unit reflect the principles of the backwarddesign process? How do the revised units eliminate the problem of activity-based, coverage approaches to curriculum design? Workbook tour Template section = blank templates and completed units pp.30-51 Coding system = circles with letters to correspond with Q=Questions, U=Understandings, T=performance task, etc. Tabbing system to show where you are (use post it notes) Worksheets and examples to help with each of the 3 stages Frequently asked questions for each stage Helpful pages: Design questions – pg. 14 Design standards-pg. 24, 6 facets – pg. 155 Roadmap – pg. 275 What Is Understanding? What does it mean to understand? Why is this the great essential question for educators today? As you start this workshop… How do you define the term “understanding”? What’s so important about understanding? Why should we be concerned with it? You’ve got to go below the surface... b To Uncover Really ‘Big Ideas, and Deeper Understanding ’ *Video Clip: “Understanding by Design” In this clip, educators and authors McTighe and Wiggins discuss their views on UbD and its long-range goals. As you begin this journey, what are your initial reactions to the ideas presented by the authors of UbD? *According to Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe: “Understanding by Design is not a prescriptive program, nor is it a philosophy of education…It is a way of thinking more purposefully and carefully about the nature of any design that has understanding as its goal…” Transfer defined and justified What is ‘transfer of learning’? ‘Transfer of learning’ is the use of knowledge and skills (acquired in an earlier context) in a new context. It occurs when a person’s learning in one situation influences that person’s learning and performance in other situations. When transfer of learning occurs, it is in the form of meanings, expectations, generalizations, concepts, or insights that are developed in one learning situation being employed in others Bigge & Shermis, 1992. 21 *According to Grant Wiggins: Learning goals can be thought of as being composed of three interrelated elements: Acquisition of new information and skill (apprehension) Make meaning of that content (comprehension); and Transfer of one’s learning to novel and important situations, issues, and problems (application). Transfer = gradual release of responsibility Consider in primary language arts I do, you watch I do, you help You do, I help You do, I watch 23 Research on transfer and misunderstanding The research is sobering: Transfer of learning is widely considered to be a fundamental goal of education. When students cannot perform tasks only slightly different from those learned in class, or when they fail to appropriately apply their classroom learning in settings outside of school, then education is deemed to have failed. Unfortunately, achieving significant transfer of learning has proven to be a difficult chore. Dating back to the beginning of [last] century, the research literature on transfer is replete with reports of failure. McKeough et al Teaching for Transfer 24 Commonly-cited deficits by educators Inability to analyze/interpret texts and events; students end up just retelling Inability to see how today’s problem in math requires the same skills we have been working on, though the content or wording of the problem is different Inability to use the new foreign language in a simulated situation that calls for what was just taught Failure to use the writing process if not prompted to do so Not answering the test question asked; failure to stop and consider: what does this question/task/problem demand? What have you experienced? Given what you teach, when do students typically fail to transfer? 25 NAEP 8th-grade test item, constructed response How many buses does the army need to transport 1,128 soldiers if each bus holds 36 soldiers? 26 Answer from 30% : “31, remainder 12”!! Remainder 12 bus 27 *Suggestions for FollowUp and Related Resources Use one or more of the following print resources to introduce UbD to your staff: (a) P. 272 (“Self-Assessment for UbD”); (b) Pp. 273-274 (“Participant Self-Assessment, Part 1 and 2”); and (c) P. 275 (“The UbD Workshop Roadmap”). *Action Planning Think: Based on this section of our institute, what is a specific action step you might take when you return to your school or district? Pair: Share your action step with another participant. Share: Share each of your action steps with your entire table group. …So How Are We Doing? What do student achievement data tell us about levels of student understanding? What can these data reveal about curriculum design, development, and implementation in public education today? Place Your Bets! How much do you think you know about student understanding as reflected in current educational trends? IMAGINE that you have $100.00 to start. Decide if each of the following statements is true or false. Depending upon how certain you are, bet the full amount you have or a part of it. Place Your Bets ONE… TRUE OR FALSE? United States students are generally showing significant gains in understanding, based upon standardized test performance. False! (I) During the past 25 years, no major gains have occurred in higher-order thinking performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). NAEP: Only 6% of students are competent in Algebra, and 15% in U.S. History, despite most students having passed courses by those titles. False! (II) Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and James Stigler’s UCLA Meta-Study of Teacher Behaviors (“The Teaching Gap” and “The Learning Gap”): a. U.S. students outperformed students in only six countries out of the 46 tested. b. Unlike high-performing countries, U.S. schools tend to emphasize practice and skill development, not thinking, inventing, and problem solving. *Place Your Bets TWO… TRUE OR FALSE? United States students are taking more advanced courses and graduating with higher grade point averages despite decreases in NAEP and other standardized test scores. *True! (I) 1. “Test Scores at Odds with Rising High School Grades”: The Washington Post, February 23, 2007 2. “High school students are performing worse overall on some national tests than they did in the previous decade, even though they are receiving significantly higher grades and taking what seem to be more rigorous courses, according to government data released recently.” *True! (II) 3. “The mismatch between stronger transcripts and weak test scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often called the nation’s report card, resonated in the Washington area and elsewhere. Some seized upon the findings as evidence of grade inflation and the dumbingdown of courses. The findings also prompted renewed calls for tough national standards and the expansion of the federal No Child Left Behind law.” *True! (III) 5. 6. “About 35 percent of 12th-graders tested in 2005 scored proficient or better in reading— the lowest percentage since the test was launched in 1992, the new data showed.” “Less than a quarter of seniors scored at least proficient on a new version of the math test…In addition, a previous report found that 18 percent of seniors in 2005 scored at least proficient in science, down from 21 percent in 1996.” *True! (IV) 7. 8. “At the same time, the average high school grade-point average rose from 2.68 in 1990 to 2.98 in 2005, according to a study of transcripts from graduating seniors. The study also found that the percentage of graduating seniors who completed a standard or mid-level course of study rose from 35 to 58 percent in that time.” “Meanwhile, the percentage who took the highest-level curriculum doubled, to 10 percent.” Place Your Bets THREE… TRUE OR FALSE? Generally, curriculum in the United States tends to emphasize critical and creative thinking rather than knowledge-recall learning… False! In the U.S., schools tend to emphasize coverage of material with many topic segments, rather than a limited set taught in depth. The U.S. curriculum tends to be a “mile-wide, inch-deep.” U.S. education tends to emphasize subjects and content rather than the learner as the center of the learning process. Place Your Bets FOUR… TRUE OR FALSE? According to Robert Marzano, author of What Works in Schools, American teachers generally have sufficient time to address the standards for which they are responsible. False! Robert Marzano (McRel): “If teachers are expected to get students to learn all of the [K-12] standards identified by their district, on average we need to expand students’ time in school by a minimum of 6,000 hours.” Place Your Bets FIVE… TRUE OR FALSE? One of the most effective ways to boost and maintain standardized test scores is to ensure that you cover every standard in your curriculum in case it is on the test. False! (I) TIMSS, Stigler, Marzano, and others report a test preparation paradox: We seem to feel the obligation to “cover” and “touch on” lots of things in case they are “on the test.” Results confirm, however, that superficial coverage of material causes poorer, not better, test results. False! (II) “What an extensive research literature now documents is that an ordinary degree of understanding is routinely missing in many, perhaps most students. If, when the circumstances of testing are slightly altered, the sought-after competence can no longer be documented, then understanding—in any reasonable sense of the term—has simply not been achieved.” Howard Gardner, The Unschooled Mind *Suggestions for FollowUp and Related Resources Engage staff members in a discussion of 21st Century “basics”: What are the life skills and habits of mind our graduates should exit with? Use the training activities in this section to introduce the six facets of understanding to your staff: How well do your students demonstrate proficiency in these six cognitive behaviors? Collaborate with other educators to create a philosophy of learning for your school or district. Analyze achievement data from your grade level, content area, school, and/or district to investigate areas of alignment with research-based conclusions (e.g., TIMSS, NAEP, Stigler’s “Teaching and Learning Gap”). Use the resources on P. 253 (“Thinking About Understanding and Design” and P. 254 (“Thinking About Understanding”) to frame a faculty meeting discussion. Backward Design at a Glance (P. 12) Stage One: Identify Desired Results: a. Long-Range Goals (Power Standards) b. Enduring Understandings & Essential Questions c. Enabling Knowledge Objectives Stage Two: Assess Desired Results: a. Use a Photo Album, Not Snapshot, Approach b. Integrate Tests, Quizzes, Reflections and Self-Evaluations with Academic Prompts and Projects Stage Three: Design Teaching and Learning Activities to Promote Desired Results: a. W.H.E.R.E.T.O. Design Principles b. Organizing Learning So That Students Move Toward Independent Application and Deep Understanding Using Research-Based Strategies *Stage 1—Desired Results “Design Questions” Established Goals: What content standards, course, or program Enduring Understandings: What specific understandings about the Essential Questions: What questions must be continually addressed to Know: What knowledge (e.g., facts, concepts, generalizations, rules, Do: What key skills and procedures will students acquire as a result of this objectives, etc., will be emphasized? What are the desired long-term accomplishments? content and work of the unit are desired? What big ideas enable such connections and transfer? What misunderstandings are predictable? ensure in-depth understanding? What thought-provoking questions link this unit to other units and to student lives? principles) questions will students be able to answer as a result of this unit? unit? *Stage 2—Assessment Evidence “Design Questions” Performance Tasks: Through what authentic Other Evidence: Through what other evidence performance task(s) will students demonstrate transfer and meaning-making of the desired results? By what criteria will performance be judged to be valid evidence of the desired learnings? (e.g., quizzes, tests, academic prompts, observations, homework, journals, etc.) will students demonstrate achievement of the desired results? *Stage 3—Learning Plan “Design Questions” Learning Activities: What acquisition of knowledge and skill is required if the goals for the unit are to be met and if the understandings are to be achieved? What meaning-making (inferences, connections, judgments) and challenges to thinking must the activities require if learners are to really understand on their own? What practice and feedback will learners need to achieve the transfer goals of the unit, as reflected in the performance tasks? UbD Instructional Design Standards (P. 24) Before we explore each of the stages of the backward-design process in detail, take some time to consider the “UbD Design Standards” on Page 24. To what extent are these standards aligned with current practices and programs in your school or district? In your opinion, which of these standards need greater emphasis? *Video Clip: “Square Area” Observe this lesson conducted by Kay Toliver. How does Ms. Toliver’s classroom reflect UbD design standards? Available through ARCO and PBS Video, GOOGLE: “ARCO Kay Toliver” for a complete catalog of her series. *Suggestions for FollowUp and Related Resources Introduce the “Prairie Days/Westward Movement” pre/post comparison activity as a way to introduce backward design to staff (pp. 6-11). Use the “Characteristics of the Best Learning Designs” on P. 267 to build consensus with other staff members about what constitutes effective instructional design. Extend your discussion of design standards by introducing the “UbD Design Standards” on P. 24. What we typically do: Identify content Without checking for alignment Brainstorm activities & methods Without checking for alignment Come up with an assessment 55 55 3 Stages of (“Backward”) Design 1. Identify desired results 2. Determine acceptable evidence 3. Plan learning experiences & instruction 56 3 Stages (with an understanding focus) 1. What should students come away understanding? 2. What is evidence of that understanding? 3. What activities will develop the understandings? 57 Stage One Desired Results: What Do We Want All Students to Understand, Know, and Be Able to Do? *Creating Your Own UbD Unit Select a potential unit topic derived from either a content area you currently teach or a professional development topic/issue for which you are responsible. (NOTE: A UbD instructional unit can last between one to four-five weeks.) Decide if you intend to work independently or if you wish to work with one or two partners. Identifying Big Ideas in Your Unit Identify the big ideas related to the topic of your unit. Be sure to check your standards, as big ideas could be explicit or implicit in the state standards. Using curricular priorities worksheet on page 19, determine and outline what is most important, important, and least important about your content, skills, and processes or concepts. 60 Stage 1: Establishing Priorities around “Big Ideas” worth being familiar with ”nice to know” 40 days important to know & do foundational knowledge & skill 40 months “big ideas” worth exploring and understanding in depth 40 years Big ideas See pages 78-79 61 61 Understandings and Essential Questions involve “Big Ideas” Is it a Big Idea? Does it – have lasting value/transfer to other inquiries? serve as a key concept for making important facts, skills, and actions more connected, coherent, meaningful, and useful? summarize key findings/expert insights in a subject or discipline? require “uncoverage” (since it is an abstract or often-misunderstood idea)? 62 Some “Big Ideas” by type concepts: migration, function, equity, text themes: “Good triumphing over evil” debates: “Nature vs. nurture” “offense vs. defense” perspective: “youth” as wise - or immature paradox: freedom involves responsibility, no force acting on a body moving at constant velocity theory: form follows function; you are what you eat principle: the “invisible hand” free markets are self-regulating (in economics), less is more (design, arts) 63 Some questions for identifying truly “big ideas” Does it have many layers and nuances, not obvious to the naïve or inexperienced person? Do you have to dig deep to really understand its meanings and implications even if you have a surface grasp of it? Is it (therefore) prone to misunderstanding as well as disagreement? Are you likely to change your mind about its meaning and importance over a lifetime? Does it yield optimal depth and breadth of insight into the subject? Does it reflect the core ideas as judged by experts? 64 Some Examples from History Standards Historical interpretation Contributions of individuals and groups, legacies of civilizations Continuity and change Conflict and cooperation Chronological thinking Use of artifacts and documents 65 Some “Big Idea” Examples of Geography Earth as our habitat Physical and human landscapes Human role in changing the earth’s surface Interrelationships between people and the environment Geography as destiny 66 Some “Big Idea” Examples for Science Science as Inquiry Measurement Diversity Cycles and Models and systems Interactions Energy Living Things Ethics and Environment 67 Some big idea examples for Language Arts Fluency Communication Vocabulary/Conceptual Development Reading to learn Literary Interpretation, Response and Analysis Writing vs Writing Process Form and structure 68 Some “Big Idea” Examples for Math Number Theory Operations Patterns Geometric expression and measurement Modeling Problem solving Data Probability, and Statistics Algebraic expressions 69 Some examples from The Arts MUSIC Variety/Types Harmony Rhythm Composition Improvisation Compose Arrange Interpret Tone VISUAL ARTS Style Perspective Contrast Color Proportion Unity/Harmony Interpretation Use of space Balance 70 *Unpacking Standards In light of the need for standards to be “unpacked,” how can we build consensus about what all students should understand (not just know and do) so that they can see the universal issues, patterns, and significance of what they are studying? How can we support students to make meaning, acquire, and transfer what they learn (and move back and forth among these three elements)? Unpacking Standards Understanding by Design suggests that standards must be “unpacked,” with educators building consensus about their levels of power or significance. In effect, some standards are more significant than others, particularly where understanding is concerned. According to UbD, unpacking standards requires the delineation of four interrelated components as part of Stage One design: The Four Major Components of Stage One Design (pp. 60-61) Established Goals: “Power standards,” i.e., those content Enduring Understandings: Statements of understanding based Essential Questions: Open-ended, interpretive questions that Enabling Knowledge Objectives (Knowledge-K and Skills-S): standards considered important enough to require “unpacking” for student understanding. upon the “big ideas” of your established goals. can be used to trigger and promote student inquiry into the enduring understandings derived from your established goals. Performance objectives that articulate what students should know (declarative knowledge/information) and be able to do (procedural knowledge) in order to achieve the designated understandings derived from your established goals/power standards. Welcome Back! Unpacking Standards Template 21stcenturyschoolteacher.com Sideways Method: Examples p. 2-5 Template p. 6 Inside Out Method: Examples p. 7-10 Template p. 11 Matrix: Examples p. 12-16 Template p. 17 Top Down: Examples p. 18-20 Template p. 21 Memorize these numbers: 17766024365911 Think of . . The . Declaration of Independence Minutes / Hours / Days / Years Emergencies! Memorize these numbers: 1776-60-24-365-911 The Understanding by Design Three-Circle Audit 1. Standards need to be interpreted and “unpacked.” 2. Staff members need to determine: a. Outer Circle: What is worth being familiar with? b. Middle Circle: What should all students know and be able to do? c. Center Circle: What are the enduring understandings students should explore and acquire? For Example… For a group of tenth-grade World History students, how would you rank each of these: The day and year the Magna Carta was signed… The historical significance of the Magna Carta… The enduring influence of significant political documents throughout the history of world civilization… Reflection Activity (1) To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “Standards have to be interpreted and ‘unpacked’ by educators. They can’t just be ‘pasted on the board.’” *If Your Unit Focuses on Curriculum Content… Consider designing the unit as a “module” within a grading period. UbD units can last between one to four-five weeks (not an entire grading period). Select a content focus that is highly significant, requires deep understanding, and/or often presents a challenge to many students. *Beginning Your Unit: Selecting Your “Established Goals” Wiggins and McTighe use the term “Established Goals” to represent what Doug Reeves calls “Power standards,” i.e., those content standards considered important enough to require “unpacking” for student understanding. *Beginning Your Unit: Some Questions to Help You Establish Priorities via Your “Established Goals” Based upon my overall purpose(s) in designing this unit: About which aspects of my content do I want learners to construct deeper meaning and overcome misconceptions and misunderstandings? About which aspects of my content do I want learners to develop a capacity for independent transfer via authentic performance tasks? About which aspects of my content do I want learners to investigate big ideas and open-ended questions in which professionals in the content area are interested? *Beginning Your Unit: Some Questions to Help You Select Your “Established Goals” What about this topic truly matters in the “real world”? What justifies teaching this? What about this topic really excites learners? What can learners do with this? What important things couldn’t you do if you didn’t learn this? Which aspects of your topic present significant challenges? *Entry Points for Your Unit Design Process Consider the “entry-point” options on P. 276: Established goals/content standards An important topic or content issue, problem, or theme A highly significant skill(s) or process(es) A significant test A key text or resource(s) A favorite activity or familiar unit that needs “revisiting” and “revamping” To What Extent Do Your Desired Results Address Understanding? Big Ideas: interdependence, heroism, patterns and Enduring Understandings: All great writing is Essential Questions: Is war inevitable? How can systems, investigation rewriting. Science can help us reveal the structural patterns and processes that shape and define our physical universe. we determine what an author means? To what extent is mathematics a language?—How can we learn to “speak” it with fluency and mastery? *Video Clip: “Welcome to Mathematics” Observe this first-day-of-school lesson taught by Kay Toliver. How does Ms. Toliver use enduring understandings and essential questions to unify and guide students’ understanding of mathematics and its significance in our world? Available through ARCO and PBS Video, GOOGLE: “ARCO Kay Toliver” for a complete catalog of her series. Introducing Enduring Understandings: A Concept-Attainment Activity (P. 107) Examine the examples on P. 107 to determine the common characteristics of effectively framed enduring understandings. Apply your list to #’s 11-16 to determine if each example is or is not a statement of enduring understanding. Enduring Understandings (P. 115) 1. Statements or declarations of understandings comprised of two or more big ideas. 2. Framed as universal generalizations—the “moral” or essence of the curriculum story. 3. Help students to “uncover” significant aspects of the curriculum that are not obvious or may be counterintuitive or easily misunderstood. 4. Formed by completing the statement: Students will understand THAT:…… Sample Enduring Understandings 1. Numbers are abstract concepts that enable us to represent concrete quantities, sequences, and rates. 2. Democratic governments struggle to balance the rights of individuals with the common good. 3. The form in which authors write shapes how they address both their audience and their purpose(s). 4. Scientists use observation and statistical analysis to uncover and analyze patterns in nature. 5. As technologies change, our views of nature and our world shift and redefine themselves. 6. Dance is a language through which the choreographer and dancer use shape, space, timing, and energy to communicate to their audience. Overarching vs.Topical Understandings (P. 114) Enduring understandings vary according to their scope and level of generalization. An overarching understanding can apply to multiple points during a student’s education; the most overarching can also apply to multiple content areas. A topical understanding is unit or timespecific and generally applies to a specific unit within the student’s course of study. Examples of Overarching and Topical Enduring Understandings Topical Overarching Mathematics allows us to see patterns that might have remained unseen. When technologies change, art forms frequently follow suit. Statistical analysis and graphic displays reveal patterns in seemingly random data. When photography emerged, Impressionists rejected realism in favor of conveying impressions of reflected light upon the human eye. Samples Understandings in History Overarching (for year or program SWUT civilizations leave legacies to help us understand our past and create our present. Topical (Unit on Greek Civilization) SWUT that the Greek contribution to the arts including architecture continue to influence artists and architects throughout western civilization. SWUT that the Greek form of a republican government became a factor in creating democracies throughout the world. 95 Environmental Education Understandings Overarching Students will understand that (SWUT) plants and animals make adaptations to their environments in order to survive. Topical SWUT Plants adapt to environments based on available energy. SWUT plant life cycles are influenced by their environments. 96 Environmental Education Understandings Overarching SWUT we have a responsibility to use appropriately and to protect our natural resources. Topical SWUT the ecosystem of rainforests promote the ongoing development of many plants. Water quality and quantity influences living organisms and human health. Appropriate procedures and processes for collecting and testing water samples can aid in devising policies to clean up water pollution. 97 An “Algorithm” for Creating Enduring Understandings (pp. 120-121) 1. Determine your “Power Standards.” 2. Identify the “big ideas” in those standards. 3. Find patterns and connections between two or more of these big ideas you wish to emphasize in your unit or course of study. 4. Use the “Students will understand that…” stem to formulate your first-draft version. 5. Revise your initial version to make it student-friendly and age-appropriate. Introducing Essential Questions: A Concept-Attainment Activity (P. 88) Examine the examples on P. 88 to determine the common characteristics of effectively framed essential questions. Apply your list to #’s 13-18 to determine if each example is or is not an essential question. Essential Questions…(P. 91) Are interpretive, i.e., have no single “right answer.” Provoke and sustain student inquiry, while focusing learning and final performances. Address conceptual or philosophical foundations of a discipline/ content area. Raise other important questions. Naturally and appropriately occur. Stimulate vital, ongoing rethinking of big ideas, assumptions, and prior lessons. Sample Essential Questions (pp. 93-103) 1. In what ways does art reflect culture as well as shape it? 2. To what extent can a fictional story be “true”? 3. Why study history? What can we learn from the past? 4. Why do societies and civilizations change as technologies change? 5. How does language shape our perceptions? 6. How would our world be different if we didn’t have fractions? 7.How do the structures of biologically important molecules account for their functions? Overarching vs.Topical Essential Questions (P. 92) Essential questions vary according to their scope and level of generalization. An overarching essential question can apply to multiple points during a student’s education; the most overarching can also apply to multiple content areas. A topical essential question is unit or timespecific and generally applies to a specific unit within the student’s course of study. Examples of Overarching and Topical Essential Questions Overarching How do effective writers hook and hold their readers? How do organisms survive in harsh or changing environments? Topical How do great mystery writers hook and hold their readers? How do animals and plants survive in the desert? Entrance Card One new learning from yesterday One question from yesterday One hope for today What we typically do: Identify content Without checking for alignment Brainstorm activities & methods Without checking for alignment Come up with an assessment 105 105 3 Stages of (“Backward”) Design 1. Identify desired results 2. Determine acceptable evidence 3. Plan learning experiences & instruction 106 3 Stages (with an understanding focus) 1. What should students come away understanding? 2. What is evidence of that understanding? 3. What activities will develop the understandings? 107 An Algorithm for Creating Essential Questions 1.Determine the “big ideas” in your enduring understandings. 2.Decide which of the big ideas you wish your students to explore and debate. 3.Use “how, why,” or to what extent” to reframe your big ideas as questions: How=process Why=cause and effect To what extent=matters of degree or kind Enabling Knowledge Objectives Now that you’ve established what you want students to understand (via enduring understandings and essential questions), you’ll need to determine: What should students know in order to achieve these understandings and complete the unit successfully? What should students be able to do in order to achieve these understandings and complete the unit successfully? How Can We Tell When Students Are Understanding? Explanation Interpretation Application Analysis of Perspectives Empathy SelfKnowledge The Six Facets of Understanding (P. 155) Explanation: Backing up claims and assertions with evidence. Interpretation: Drawing inferences and generating something new from them. Application: Using knowledge and skills in a new or unanticipated setting or situation. Perspective: Analyzing differing points of view about a topic or issue. Empathy: Demonstrating the ability to walk in another’s shoes. Self-Knowledge: Assessing and evaluating one’s own thinking and learning: revising, rethinking, revisiting, refining. Experiencing the Six Facets Select a partner. Take turns responding to the following prompts, each of which asks you to use one of the six facets of understanding. As you answer each question, how are you using each facet? What similarities and patterns can you identify? Explanation Agree or Disagree? “Those who fail to learn from the past are condemned to repeat it…” Explain your response by providing evidence to support your opinion. Interpretation Brainstorm five (5) or more ways that teaching is like a popcorn popper… Application Wiggins and McTighe assert that understanding is qualitatively different from knowing or being able to do something. Apply this assertion to your own life by describing an experience when you moved from knowing or being able to do something to understanding it… Perspective Compare the idea of “back to the basics” as it might have been presented in the 1950’s to the “basics” of education in the 21st Century. Empathy Imagine that you are a student in a school in which you currently work. Describe what you see, feel, and think as you go through your day… Self-Knowledge How have your views on the teaching-learning process changed since you first entered the profession of education? A Reflection Checkpoint With which of the following “facets of understanding” do your students generally perform well? With which do they have trouble? Why? a. Explanation b. Interpretation c. Application d. e. f. Perspective Empathy Self-Knowledge Resources for Using the Six Facets of Understanding 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. As you introduce Understanding by Design to your school or district, you may wish to use the following resources related to the six facets of understanding: P. 155=Operational Definitions P. 156=Questioning for Understanding Pp. 157-160=Performance Task Ideas P. 161=Performance Verbs Pp. 162-166=Performance Task Ideas The Structure of Knowledge (pp. 65-68) Declarative (Know) Facts Concepts Generalizations Theories Rules Principles Procedural (Do) Skills Procedures Processes Declarative Knowledge (Know) Facts: 1776; Annapolis is the capital of Maryland; Lyndon Johnson succeeded John F. Kennedy. Concepts: interdependence; scientific method; equivalent fractions; grammar and usage Generalizations: Tragic heroes frequently suffer because of a failure to recognize an internal character defect; Technology changes frequently produce social and cultural changes. Theories: Einstein’s Theory of Relativity; Natural Selection Rules: The Pythagorean Theorem; rules for pronouncing sound-symbol combinations in English Principles: Newton’s Laws; the Commutative Principle Procedural Knowledge (Do) Skill: Focus a microscope; Decode the meaning of a word using a context cue. Procedure: Prepare and analyze a slide specimen; Summarize the main idea of a paragraph or passage. Process: Collect a variety of leaf specimens and compare their structures using a microscope; Trace the development of an author’s theme in a work of literature. To What Extent Do Your Desired Results Contain Objectives That Emphasize the Six Facets of Understanding? (P. 161) The Six Facets: explain, interpret, apply, analyze perspectives, express empathy, demonstrate self-knowledge and metacognitive awareness Know: facts, concepts, generalizations, rules and principles Do: skills, procedures, processes For Example… Students will be able to: 1. 2. 3. 4. Explain the significance of the following facts about the American Civil War. Interpret the meaning of and apply the following concepts to the analysis of cause and effect patterns in labs focusing on chemical and physical changes in matter. Analyze and explain the origins of conflicting perspectives about the Kennedy assassination. Express empathy for the characters by participating in a role-play or simulation of events from the novel. Knowledge and Skills Create a list of knowledge and skills for the EU’s, EQ’s you have listed in the Goals section. Enter these on Stage 1 under know and be able to do in your template Examine the performance indicators or sub-standards in your state standards documents for the most important (not necessarily all) “know and do” statements Content knowledge will usually be constructed with nouns and be related to specific processes, procedures, principles, formulas, facts etc. Skills will generally begin with a verb and be focused on what you want students “to do” or “how to”. Many skills are listed in performance indicators It is important that knowledge and skills are aligned with the other components in order to assess and to design specific lessons later in Stages 2 and 3. 126 Enabling Knowledge Objectives Students will be able to: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Explain…by… Apply…by… Interpret…by… Analyze perspectives…by… Express empathy…by… Demonstrate self-knowledge…by… Examining Sample Stage One Unit Designs Examine the sample Stage 1 design on pages 5253 of the workbook. How are the principles for designing Stage One desired results used here? Compare the Stage 1 design from pages 54-44 to the sample one-page designs on pages 32-35 and the two-page designs on pages 38-45. Which of the various designs do you prefer? Why? Which design principles from Stage 1 would you include in your school or district’s mandated lesson or unit design policies? Why? *Reviewing Your Stage One Design (P. 126, “Design Checklist-Stage 1) Ensure alignment among your established goals, EUs, EQs, and K-S objectives. Avoid too many enduring understandings (e.g., 1-3 max) and essential questions (e.g., 2-5 max). Balance thematic and competency-based understandings and questions. Revise understandings that are truisms, facts, superficial, or excessively global and unfocused. Revise essential questions that are factual, too skillsfocused, teacherly, narrow, or irrelevant outside of class. Be sure that your K-S objectives are clearly related to your established goals and related EUs and EQs. *Resources for Stage One Desired Results Design As you introduce Understanding by Design to your school or district, you may wish to use the following resources related to Stage One (Desired Results): 1. Pp. 120-125 (“Unpacking Goals”) 2. P. 126 (“Design Checklist”—Stage 1) 3. Pp. 127-130 (“Stage 1 Draft Designs for Review”) 4. Pp. 131-133 (“Frequently Asked Questions About Stage 1”) *Action Planning Think: Based on this section of our institute, what is a specific action step you might take when you return to your school or district? Pair: Share your action step with another participant. Share: Share each of your action steps with your entire table group. Stage Two Determining Assessment Evidence: How will we diagnose, monitor, and evaluate students’ achievement of Stage One desired results? Addressing These Trends Through Student Engagement… In your opinion, what does it mean for students to be “engaged” in learning? Is there a time you can remember when, as a student, you were actively engaged in the learning process? Recognizing the limits of testing 134 “Evaluation is a complex, multi-faceted process. Different tests provide different information, and no single test can give a complete picture of a student’s academic development. -- from CTB/McGraw-Hill Terra Nova Test Manual 134 *Stage 2—Assessment Evidence “Design Questions” Performance Tasks: Through what authentic Other Evidence: Through what other evidence performance task(s) will students demonstrate transfer and meaning-making of the desired results? By what criteria will performance be judged to be valid evidence of the desired learnings? (e.g., quizzes, tests, academic prompts, observations, homework, journals, etc.) will students demonstrate achievement of the desired results? Assessing Understanding: Some Starting Points… Assessment and instruction are inextricably linked. The nature of your desired result(s) will determine the type(s) of assessment task you use to monitor student achievement. When assessing for understanding, more than selected-response test items (truefalse, fill in the blank, multiple choice) are required. Curricular Priorities and Assessment Methods (P. 141) Traditional quizzes and tests (selected response)……. Quizzes and tests (constructed response)……. Performance tasks and projects… Performance tasks and projects (complex, open-ended, authentic)……... Assessing Your Assessments… (P. 142) Do you select the appropriate assessment tool or process to assess each desired result? Do you use a range of assessment tools, rather than just tests and quizzes? Do you strive for a photo album, not a snapshot, of student performance data? Does your photo album provide a full portrait of what your students know, do, and understand relative to your desired results? Assessing Your Assessments (P. 142) Do you make use of… Tests and quizzes that include constructedresponse items? Reflective assessments (reflective journals, think logs, peer response groups, interviews)? Academic prompts with a FAT-P (audience, format, topic, purpose) clearly stated? Culminating performance assessment tasks and projects? A Self-Reflection Activity (P. 143) 1. Complete the questionnaire on page 143, “Sources of Assessment Evidence: Self-Assessment.” 2. Compare your responses to those of one or more participants at your table. On which areas do you agree there is a high level of use? In which areas do you agree there is a need for improvement or expanded emphasis? *Beginning Your Stage Two Design Ensure that all Stage One desired results are assessed in a balanced way (esp. your EUs and EQs). Avoid assessments that are too focused on discrete content and do not do justice to the big ideas of your unit. Be sure that transfer tasks are framed as true performance tasks (e.g., authentic context, purpose, audience, etc.). Provide key information on criteria for evaluation: “look-for’s,” rubrics, scoring guides. Sample Reflective Assessment Activities 1. Reflective Journal Entries: How well do you understand this passage? What are the main ideas from this lesson? What did this material mean to you? 2. Think Logs: How would you describe the process of classification? How has your approach to problem-solving changed during this unit? 3. Self-Evaluations: Based upon our evaluation criteria, what grade would you give yourself? Why? 4. Peer Response Group Activities: What can you praise about the work? What questions can you pose? What suggestions can you make for polishing the product? 5. Interviews: Tell me about your perceptions of this project. What do you consider to be your strengths and areas in need of improvement? The Academic Prompt A structured performance task that elicits the student’s creation of a controlled performance or product. These performances and products should align with criteria expressed in a scoring guide or rubric. Successful prompts articulate a format, audience, topic/content focus, and purpose. A Sample Academic Prompt with a FAT-P Think about a time when you were surprised (topic). Write a letter (format) to a friend (audience) in which you describe that experience. Use a logical narrative sequence with concrete sensory details to help your friend understand what this event was like and how you experienced it (purpose). Activity Pages 168-169 Choose performance task example and locate the FAT-P elements. Distinguishing Between an Academic Prompt and a Culminating Performance Task and Project (pp. 168-169) In designing performance tasks, we need to ask ourselves: What is the level of independent transfer students are expected to demonstrate? If students are still in the area of “guided practice,” an academic prompt may be more appropriate; if students are expected to demonstrate independent transfer and a high level of conceptual understanding, a culminating project or authentic performance task (cornerstone performance) may be most appropriate. Review the “Performance Task Samples” on pages 168-169 of the workbook. In your opinion, which ones are academic prompts (because they are highly teacher-guided and mediated) and which ones are closer to independent projects or cornerstone performances (because they require extended student time, independent transfer, and a high degree of conceptual application)? Elements of an Effective Performance Task and Culminating Project G=real-world goals R=real-world role(s) A=real-world audience S=real-world situation P=real-world products and performances S=standards for acceptable performance A Sample G.R.A.S.P.S. You are a member of a team of scientists investigating deforestation of the Amazon rain forest. You are responsible for gathering scientific data (including such visual evidence as photographs) and producing a scientific report in which you summarize current conditions, possible future trends, and their implications for both the Amazon itself and its broader influence on our planet. Your report, which you will present to a United Nations subcommittee, should include detailed and fullysupported recommendations for an action plan which are clear and complete. Follow-Up Activity Use the G.R.A.S.P.S. design elements to create a powerful culminating performance task or project for a unit you teach. Assessing Performance Tasks Modified Holistic Scoring Rubrics Analytic-Trait Rubrics Analytic Scoring Guides Modified Holistic Scoring Rubric (P. 182) 3=All data are accurately represented on the graph. All parts of the graph are correctly labeled. The graph contains a title that clearly tells what the data show. The graph is very neat and easy to read. 2=Data are accurately represented on the graph or the graph contains only minor errors. All parts of the graph are correctly labeled or the graph contains minor inaccuracies. The graph contains a title that generally tells what the data show. The graph is generally neat and readable. 1=The data are inaccurately represented, contain major errors or are missing. Only some parts of the graph are correctly labeled, or labels are missing. The title does not reflect what the data show, or the title is missing. The graph is sloppy and difficult to read. The Analytic-Trait Rubric (P. 188) Traits Scale Understanding Weights: 65 percent Performance or Performance Quality 35 percent 4 Shows a sophisticated understanding of relevant ideas and processes… The performance or product is highly effective… 3 Shows a solid understanding of the relevant ideas and processes… The performance or product is effective… 2 Shows a somewhat naïve or limited understanding of relevant ideas or processes… The performance or product is somewhat effective… 1 Shows little apparent understanding of the relevant ideas and processes… The performance or product is ineffective. Analytic Scoring Guide 50%=Content: Clearly-presented thesis statement with fullydeveloped supporting ideas and balanced evidence to make a compelling and convincing argument. 25%=Organization: Consistent support of thesis statement with all ideas and supporting evidence aligned with the controlling ideas of the composition. Consistent attention to the use of transitional expressions and other techniques to ensure coherence and clarity. 25%=Editing: Elimination of major grammar and usage errors with clear attention to correct syntax and sentence variety. Examining Sample Stage Two Unit Designs Examine the sample Stage 2 design on pages 5455 of the workbook. How are the principles of balanced assessment design used here? Compare the Stage 2 design from pages 54-44 to the sample one-page designs on pages 32-35 and the two-page designs on pages 38-45. Which of the various designs do you prefer? Why? Which design principles from Stage 2 would you include in your school or district’s mandated lesson or unit design policies? Why? *Reviewing Your Stage Two Design (Design Checklist—Stage 2, P. 207) Ensure that all Stage One desired results are assessed in a balanced way (esp. your EUs and EQs). Avoid assessments that are too focused on discrete content and do not do justice to the big ideas of your unit. Be sure that transfer tasks are framed as true performance tasks (e.g., authentic context, purpose, audience, etc.). Provide key information on criteria for evaluation: “look-for’s,” rubrics, scoring guides. Resources for Stage Two Assessment Design 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. As you introduce Understanding by Design to your school or district, you may wish to use the following resources related to Stage Two (assessment design): Pp. 168-169=Performance Task Samples P. 172=G.R.A.S.P.S. Design Template Pp. 173-179=G.R.A.S.P.S. Resources P. 180=Self-Test Assessment Ideas Pp. 181-196=Scoring Tools Resources Pp. 197-207=Performance Task Ideas P. 233=Three Types of Classroom Assessments P. 234=Informal Checks for Understanding Pp. 235-236=Assessing and Addressing Misunderstandings *Action Planning Think: Based on this section of our institute, what is a specific action step you might take when you return to your school or district? Pair: Share your action step with another participant. Share: Share each of your action steps with your entire table group. Stage Three Designing TeachingLearning Activities: How can we promote student achievement of Stage One desired results as confirmed by their performance on Stage Two assessments? A Stage Three Essential Question How can schools and districts promote instructional practices that reinforce the engagement, achievement, and understanding of all learners? *Stage 3—Learning Plan “Design Questions” Learning Activities: What acquisition of knowledge and skill is required if the goals for the unit are to be met and if the understandings are to be achieved? What meaning-making (inferences, connections, judgments) and challenges to thinking must the activities require if learners are to really understand on their own? What practice and feedback will learners need to achieve the transfer goals of the unit, as reflected in the performance tasks? *Examples in Action (1): Learning to Tie Your Shoes Student is taught how to tie their shoes (A). Students practice tying their shoes (A). Students draw or speak the steps for tying shoes (M). Students discuss the pro’s and con’s of laces vs. Velcro and different methods of tying (M). Students teach others how to tie their shoes (T). *Examples in Action (2): Learning Newton’s Laws of Motion Students are given four demonstrations of physical events (pendulum, shooter of pellets, care slowing down, sling) and asked to explain them in terms of Newtonian principles and the question: “Why does that move the way it does?” (M). Students are asked to generalize from laboratory data (M). Students read and discuss the textbook’s presentation of the three laws of Newton and take a quiz on their reading (A). Students build a working roller coaster based on their learning about forces, vectors, and Newton’s laws (T). *Examples in Action (3): Analyzing Hamlet Teacher lectures on the life of Shakespeare, the Globe Theatre, and the relationship of Hamlet to Shakespeare’s career, stopping for classroom discussion and student questions (A). Students participate in a Socratic seminar on Hamlet (M). Students identify real-life persons who resemble Hamlet, providing evidence to explain their choices (M). “What’s the diagnosis?”—Students assume the role of psychologist, analyzing Hamlet’s motivation and behavior patterns (T). What Can We Observe in a Classroom That Promotes Student Understanding? (pp. 268-269) As we begin to explore the design of teaching and learning activities that promote student understanding (Stage 3), consider the “Observable Indicators of Teaching for Understanding” identified on pages 268-269. In your opinion, how often are these indicators present in classrooms with which you are familiar? Which ones would you like to see more of? Why? *Key Suggestions for Effective Stage Three Design (P. 267) Align the learning experiences with your Stage 1 Desired Results, emphasizing understanding of big ideas. Include your diagnostic, formative, and summative assessment tasks as part of your teaching-learning design sequence. Make the purpose/rationale for each learning experience/activity clear. Be sure that EUs and EQs are central to your unit and revisited throughout it. Build student learning toward transfer and personal meaning-making; avoid too much teacher-centered direct instruction that does not lead to these two priorities. Make the unit a “whole” of learning experiences which logically flow and coherently build and come together; avoid a grab-bag of isolated activities and lessons that merely “cover” discrete content goals. Emphasize student meaning-making and/or transfer; avoid too much emphasis upon content coverage or acquisition. Consider areas of your unit where differentiation of content, process, and products can occur to accommodate varying student readiness levels, interests, and learning profiles. An Introduction to W.H.E.R.E.T.O. (P. 212) UbD suggests that when designing instructional activities (Stage 3), educators make use of a set of design principles called W.H.E.R.E.T.O. These design principles form a kind of “blueprint” for designing teaching and learning activities that promote deep understanding and transfer. Designing Instructional Activities to Promote Understanding W=Where are we going? Why are we going there? In what ways will we be evaluated? H=How will you hook and engage my interest? E=How will you equip me for success? R=How will you help me revise, rethink, refine, and revisit what I am learning? E=How will I self-evaluate and self-express? T=How will you tailor your instruction to meet O=How will you organize your teaching to my individual needs and strengths? maximize understanding for all students? *Video Clip: “W.H.E.R.E.T.O. in Action” Observe these classrooms in action. How does each of them reflect the W.H.E.R.E.T.O. design principles? Available through ASCD DVD, Moving Forward with Understanding by Design. “W” Essential Questions (pp. 215-216) Articulation of Goals: Where are we going in this unit or course? What are our goals and standards? What resources and learning experiences will help us achieve them? Communication of Expectations: What is expected of students? What are the key assignments and assessments? How will students demonstrate understanding? What criteria and performance standards will be used for assessment? Establishment of Relevance and Value: Why is this worth learning? How will this benefit students now and in the future? Diagnosis: From where are students coming? What prior knowledge, interests, learning styles, and talents do they bring? What misconceptions may exist that must be addressed? The “H” Concept At the beginning of key juncture points in your teaching/unit, “hook” students’ imagination and motivation by engaging them in thought-provoking, interactive, and intriguing learning activities that anticipate or foreshadow key unit content. FOR EXAMPLE, at the beginning of a life science or biology unit on the human body: Babies are born with 300 bones. Adults have 206. A sneeze can travel more than 100 miles per hour. Every person has a unique tongue print. A fingernail or toenail takes about six months to grow from base to tip. The heart circulates the body’s blood supply about 1,000 times each day. The average human scalp has 100,000 hairs. If put end to end, all the blood vessels in the body would stretch 62,000 miles (or 2.5 times around the Earth). If a man never trimmed his beard, it would, on average, grow to nearly 30 feet. Every square inch of your body has about 3.2 million bacteria on it. (“The Inside Story,” The Washington Post, P. C12, May 7, 2007) FOR EXAMPLE, at the beginning of a history unit on the American presidency: Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860; John F. Kennedy was elected President in 1960. Both were particularly concerned with civil rights. Both had wives who lost children while living in the White House. Both Presidents were shot on a Friday. Both Presidents were shot in the head. Lincoln’s secretary was named Kennedy, Kennedy’s Lincoln. Both were assassinated by Southerners and were succeeded by Southerners named Johnson. Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Lincoln, was born in 1839; Lee Harvey Oswald, Kennedy’s assassin, was born in 1939. Both assassins were known by their three names; both names are composed of fifteen letters. Lincoln was shot at the theatre named “Ford” and Kennedy was shot in a car called “Lincoln” made by “Ford.” Lincoln was shot in a theatre and his assassin ran and hid in a warehouse; Kennedy was shot from a warehouse and his assassin ran and hid in a theatre. Booth and Oswald were both assassinated before their trials. A week before Lincoln was shot, he was in Monroe, Maryland; A week before Kennedy was shot, he was with Marilyn Monroe. FOR EXAMPLE, ask students what they conclude about the following unusual information…: Take your height and divide by eight. That is how tall your head is. No piece of paper can be folded in half more than seven times. The first product to have a bar code was Wrigley’s gum. Earth is the only planet not named after a pagan god. A Boeing 747’s wingspan is longer than the Wright brothers’ first flight. Three percent of pet owners give Valentine’s Day gifts to their pets. Thirty-one percent of employees skip lunch entirely. According to research, Los Angeles highways are so congested that the average commuter sits in traffic for 82 hours a year. The 1912 Olympics was the last Olympics that gave out gold medals made entirely out of gold. What can you conclude about the following…? Falling is the most common nightmare. Americans consume five tons of aspirin a day. Most men part their hair to the left for no apparent reason. Sixty-seven percent of Americans think they are overweight. Americans throw away 27 percent of their food each year. Twenty-five percent of all people snoop in friends’ medicine cabinets. People typically spend a year of their lives looking for things they have lost. One out of every 10 children sleepwalks. Thirty-six percent of people choose pizza for the one food they would eat if they could only eat one food. “H” Strategies (P. 217) Odd facts, anomalies, counterintuitive examples Provocative entry questions Mysteries and engaging anecdotes or stories Challenges Student-friendly problems and issues Experiments and predictions of outcomes Role-plays and simulations activities Sharing personal experiences Allowing students choices and options Establishing emotional connections Humor “E” Essential Questions (pp. 218-219) Experiential and Inductive Learning:What experiential or inductive learning will help students to explore the big ideas and essential questions? Direct Instruction: What information or skills need to be taught explicitly to equip students for successful achievement of desired results? Homework and Other Out-of-Class Experiences: What homework and other out-of-class experiences are needed to equip students to achieve desired results and complete expected performances? “R” Essential Questions (pp. 221-222) Rethink:What big ideas do we want students to rethink? How will your design challenge students to revisit important ideas? Revise or Refine: What skills need to be practiced or rehearsed? How might student products and performances be improved? Reflect: How will you encourage students to reflect on their learning experiences and growing understanding? How will you help them to become more meta-cognitive? Sample “E” Questions (P. 223) What do you really understand about …….? What questions and uncertainties do you still have? What was most and least effective in ….? How could you improve …..? How would you describe your strengths and needs in…? What would you do differently next time? What grade or score do you deserve? Why? How does what you’ve learned connect to other learnings? How have you changed your thinking? How does what you’ve learned related to your present and future? What follow-up work is needed? “T” Essential Questions (P. 224) Content: How will you accommodate different knowledge and skill levels? How will you address a variety of learning modalities and preferences? How will you use a range of resource materials? Process: How will you vary individual and group work? How will you accommodate different learning style preferences and readiness levels? Product: To what extent will you allow students choices in products for activities and assignments? How will you allow students choices for demonstrating significant understandings? “O” Essential Questions (P. 225) Conceptual Organization Along a Developmental Continuum: How will you help students to move from initial concrete experience toward growing levels of conceptual understanding and independent application? Coverage: What aspects of your unit or program are most appropriately and effectively addressed in linear, teacherdirected, or didactic fashion? “Uncoverage”: What is most appropriately and effectively “uncovered” in an inductive, inquiry-oriented experiential manner? Applying Stage 3 1. How is W.H.E.R.E.T.O. the “blueprint” for Stage Three learning activities? 2. How would you explain each of the W.H.E.R.E.T.O. elements to a colleague with whom you work? Examining Sample Stage Three Unit Designs Examine the sample Stage 3 design on Page 56 of the workbook. How are the W.H.E.R.E.T.O. design elements used here? Compare the Stage 3 design from Page 56 to the sequential, calendar-based design on Page 57. Which of the two designs do you prefer? Why? Which design principles from Stage 3 would you include in your school or district’s mandated lesson or unit design policies? Why? *Reviewing Your Stage Three Design (Design Checklist—Stage 3, P. 238) Align the learning experiences with your Stage 1 Desired Results, emphasizing understanding of big ideas. Make the purpose/rationale for each learning experience/activity clear. Be sure that EUs and EQs are central to your unit and revisited throughout it. Build student learning toward transfer and personal meaning-making; avoid too much teacher-centered direct instruction that does not lead to these two priorities. Make the unit a “whole” of learning experiences which logically flow and coherently build and come together; avoid a grab-bag of isolated activities and lessons that merely “cover” discrete content goals. Emphasize student meaning-making and/or transfer; avoid too much emphasis upon content coverage or acquisition. Include your diagnostic, formative, and summative assessment tasks as part of your teaching-learning design sequence. Consider areas of your unit where differentiation of content, process, and products can occur to accommodate varying student readiness levels, interests, and learning profiles. Resources for Stage Three Design of Teaching-Learning Activities 1. 2. 3. As you introduce Understanding by Design to your school or district, you may wish to use the following resources related to Stage Three (design of teaching-learning activities): P. 237=The Logic of Design vs. the Sequence of Teaching P. 238=Design Checklist—Stage 3 Pp. 239-240=Frequently Asked Questions About Stage 3 *Action Planning Think: Based on this section of our institute, what is a specific action step you might take when you return to your school or district? Pair: Share your action step with another participant. Share: Share each of your action steps with your entire table group. So Far, We’ve Explored… Changes in our society necessitating the need to emphasize student engagement. The need to emphasize student understanding, not just knowledge-recall learning. The power of a core and conceptually-organized curriculum built upon high expectations for all students. The necessity of differentiating assessment and instruction. The power of using research-based instructional practices to promote student engagement. Contact Information Donnell E. Gregory: Email: Dgregory@dgregoryassociates.com Phone: 937.673.8025 Donna Herold: Email: donnaher@spokaneschools.org 509.979.2521 http://www.21stcenturyschoolteacher.com 194