9-11

advertisement

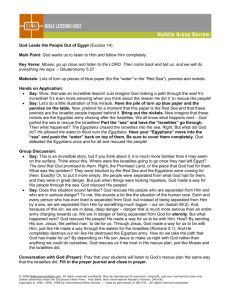

A sermon preached on the 10th anniversary of 9/11 It was a Tuesday afternoon, and I had just finished triple German. Rather strangely we had been taking about the Taliban in Afghanistan during the lesson – pushing all our German vocab to the limit! Somehow, and I can’t remember quite how it happened, but word spread through school that something had happened. Being in Northern Ireland, we did have regular-ish bomb practices, along with fire drills, but this was something different. I bumped into my younger brother in the halls and we went to the sixth form common room – and were astounded by what we saw on the tiny telly. It was as if it as was one of those 1970s aircraft disaster films, and if I remember rightly we all just stood there whilst we watched the second plane crash into the second twin tower in New York. I remember the absolute silence in the school that afternoon and evening; we were a pretentious old boarding school in the sticks in Northern Ireland,, in a country which had been torn apart by 30 yrs of UDF, Protestant and IRA Catholic terrorism, but somehow this had more impact, it was the event which really marked the beginning of the new millennium, which was still very fresh and young. I tell you my own memories because we all could tell each other how we felt, what we were doing when we heard about the terrorist attacks in the States ten years ago. These horrific memories and the retelling of them are all part of our own stories; of the stories of our corporate and collective life, defining moments in the C21st. Reminiscences of this sort, along with events in our own personal lives are what make us who we are. And this is something that has been integral to human society for millennia; and this story telling, this setting life in context is what we have been exploring throughout the summer with sermons based on the Old Testament reading. And today we have something similar. We hear of how the Israelites, who have endured hell in Egypt, a life worse than slavery and finally they leave, chased by the Egyptian army. We hear how God created confusion between the Israelites and the Egyptian army who was chasing them – after all the Israelites were important slave workers, contributing hugely to the Egyptian economy. And they ran out of Egypt not by the M1, by the road – there would have been too many guards to block their way, but they leave Egypt by the little back roads, and lo they come to the sea. I’m sure you can imagine their panic, with the well equipped Egyptian army with its C8th BC equivalents of air missiles, artillery, tanks quickly making up the distance between them. We all know the story: Moses holds up his hand over the sea, divides the waters so the Israelites can pass through to safety. Which they do. And then the Egyptians follow; probably marvelled at this, and then , as the writes of Exodus writes, God tells Moses to stretch out his hand again, so that the waters close in on the Egyptians and drown them all; from brigadiers, colonels, down to sergeants and privates, in a boastful phrase the writer of Exodus writes ‘not one of them remained’ . The Israelites, delighted to be delivered from the Egyptians sing and dance ‘I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously; horse and rider he has thrown into the sea’ is how the next chapter of Exodus starts. And you can understand the joy and jubilation of the Israelites as they see their enslavors sinking to their deaths as the waters come over them. And symbolically it is important – it makes the beginning of the deliverance of the Children of Jacob and begins to move towards the covenant made between Moses, on behalf of the people with God on Mount Sinai. But I must confess that I feel very uneasy about this jubilation. At theological college during daily morning prayer we said the canticle ‘I will sing gloriously’, as we celebrated the deaths of these Egyptians. Yes, the Egyptians did treat the Israelites poorly, but, they were, we are celebrating the massacre of human life. Dare I suggest that we are celebrating in a terrorist act? The slaughter of many people? Of husbands, fathers, sons? I read this into today’s first reading because terrorism is almost a day-to –day part of modern life; this week 10 ppl were blown up outside a courthouse in Delhi; as I said earlier, growing up with 2 army officers as parents in Northern Ireland meant the threat of terrorism was always there – car checks in the morning. And, more over, terrorist and terrorism has often used religion as a reason to justify violence: to justify actions against those who are different from us.; the Israelites and the Egyptians, the Protestants v the Catholics in Northern Ireland, Islamic extremists v Christianity today. Now this is difficult. Difficult to understand, difficult to explain; I’ve struggled with it over the last week as I’ve been preparing this sermon. We can easily see how religion can be used to support violence and terrorism. Some interpret one religion as being the only one, as the only way to live and all other , as they see it, rival religions’ must be exterminated. They forget that there are many faiths for our one shared humanity. Put another way, they think ‘ those who don’t share my faith don’t share my humanity.’ Which of course is wrong. It is very wrong. All of us on this small planet share in each other’s humanity. We all have our own individual stories, seen, lets say as threads, and occasionally these threads are woven together to form the tapestry of our shared humanity. We all have unique stories, but we all share in certain key points, and 9/11 is one of those. And just as we all share in certain key points, so too should we share in certain key characteristics of humanity. I don’t know very much about weaving, but I know you have two sets of threads at right angles to each other; let’s think of the downward threads as events such as 9/11, the birth of a child, your marriage, your partner’s death; major events which have shaped your lives; and then the sideward threads are key characteristics intrinsic to humanity. And one of these characteristics is forgiveness. We hear in our gospel today that we are to forgive seven times seventy seven. Now my maths is awful, but even I know that this means we are to forgive an infinite number of times. Forgiveness is hard. If it is to be genuine, if it is to be generous, then it must be difficult, because it reciprocal. Remember the Lord’s prayer ‘forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us.’ Gerhart von Rad, a German Biblical scholar who was radically opposed to Nazism writes that forgiveness lies at the heart of our faith in God and our love for one another; he states that it is one of the core threads around which our lives’ stories should be woven. So today is the 10th anniversary of 9/11, when we remember those who died in the attacks on the States, and also those soldiers, civilians who have died in the conflicts related to 9/11. Let us use this solemn day to call back our memories of that awful day, to think of how we use our faith in shaping our lives, and let us remember the tensions we find in our religion, but also let us think of our common humanity. And so, I invite you to stand and spend a moment in silence honouring those who have died and praying for the world today, as we remember we all have a common humanity and a common story. © Andrew Allen 2011