Policy Implementation

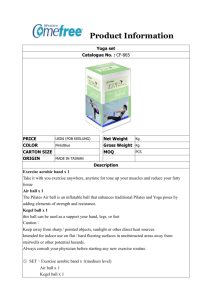

advertisement

北京师范大学 教育研究方法讲座系列 (2): 教育政策研究 第八讲 教育政策实施过程的研究(二) (B) Beyond Top and Bottom Dichotomy: The Third Generation of Implementation Theory A. Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981): 1. Distinction between policy-centered and action-centered approaches: In reviewing the studies of policy implementation before the 1980s, Barrett and Fudge classify them into two approaches a. Policy-centered approach: This approach takes the policy mandate as the foundation and crux of the implementation process. i. It defines the process of implementation is the logic and administrative lock-steps of "putting the policy into effect". ii. The approach accepts the perspectives of the policy makers as the primary concerns and implementation is but the act of carrying out the policy-makers' prescription to the full. iii. Accordingly, implementation is construed as a purely administrative task of imposing of control and soliciting compliance b. Action-centered approach: i. It defines policy implementation as series of actions, i.e. a project or an agency, through which "getting something done" or "making something happen" is the primary goal rather than simply securing the compliance of the "street-level bureaucrats" ii. The approach conceived policy implementation as performance rather than conformance. The performance or action is environment-dependent and context-dependent, hence constraints imposed by the environment as well as perspectives held by interaction partners must be taken into consideration as the implementation process unfolds in the field iii. According, implementation is conceived as both a negotiating process as well as responsive process 2. Policy implementation as process of structuration a. Susan Barrett specifically underlines the influence of Giddens' Theory of Structuration on her formulation the Policy-Action Model. (2004, p. 256-257) b. Three conceptual constituents in the Theory of Structuration (Giddens, 1984) i. The agency and the agent: - Agency is conceived as a flow of intentional action, i.e. a project: - Agent is defined as knowledgeable human actor, who W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 1 possesses the capacity of carrying out intentional action ii. The Structure: Structure refers to those rules and resources, which "make possible for discernibly similar social practices to exist across varying spans of time and space.' (Giddens, 1984, p.17) In other words, it refers to "rules and resources recursively implicated in the reproduction of social systems." (Giddens, 1984, p. 377) iii. Structuration: "Analysing the structuration of social systems grounded in the knowledgeable activities of situated actors who draw upon rules and resources in the diversity of action contexts, are produced and reproduced in interaction. …The constitution of agents and structures are not two independently given sets of phenomena, a dualism, but represent a duality. According to the notion duality of structure, the structural properties of social systems are both medium and outcome of the practices they recursively organized. Structure is not 'external' to individuals: as memory traces, and as instantiated in social practices, it is in a sense more 'internal' than exterior to their activities…. Structure is not to be equated with constraint but is always both constraining and enabling." (P.25) For example, the structure of a language system both constraints and enable agents, who are knowledgeable to that language, expressing herself and communicating with other agents in daily interactions. 3. Policy implementation as action-and-response process By applying the duality of structure and theory of structuration to the study of policy implementation, policy and its implementation can be reformulated as follows: a. Policy can be conceived as a structure, i.e. rules and resources implicating the recurrence of particular sets of social practices. To take EMI policy as an example, it implicates that teachers and students will recursively adopt English as medium of instruction in their lessons. b. The duality of the structure can be illustrated by the fact that EMI policy as a structure is both the medium and the outcome of implementation process. c. Accordingly, policy implementation can no longer be conceptualized as a single linear progression of policy —→ action, but as a recursive and ongoing process of actions and responses. B. Paul A. Sabatier’s advocacy coalition framework W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 2 1. Sabatier (1986/1993) puts forth the “advocacy coalition framework” as a means to synthesize the top-down and bottom-up models in policy implementation. 2. By advocacy coalition, Sabatier refers to “actors from various public and private organizations who share a set of beliefs and who seek to realize their common goals over time” in a specific policy system (domain). (Sabatier, 1993, p. 284; and Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1999, p. 120) From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. a. The composition of an advocacy coalition is made up of a variety of groupings: (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1999, p. 118-119) i. administrative agencies, ii. legislative committee, iii. interest groups, iv. journalists, researchers, and policy analysts, and v. actors at all levels of government active in policy formulation and implementation. b. The unit of analysis of policy implementation is neither the top-down officials and their policy directives nor the street-level bureaucrats and their accommodating strategies, but is the advocacy coalitions in a specific policy problem or issue, i.e. policy subsystem, such as higher education or air pollution control. (Sabatier, 1993, 284) c. The delineative line or the integrative force of an advocacy coalition is its belief system, which can be differentiated into three levels. (Sabatier, 1993, p. 287; and Sabatier, 1999, p. 133) i. The deep core: Fundamental normative and ontological axioms ii. The policy core: Fundamental policy position concerning the basic strategies for achieving core values within the subsystem iii. Instrumental decisions and information searches for necessary to implement policy core d. A longer time frame, i.e. a decade or more should be adopted in policy implementation so as to allow the policy process “to complete at least one formulation/implementation/reformulation cycle, to obtain a reasonably accurate portrait of success and failure, and to appreciate the variety of strategies actors pursue over time.” (Sabatier, 1993, p. 119) W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 3 RELATIVELY STABLE PERAMETERS 1. Basic attributes of the problem area (good) 2. Basic distribution of natural resources 3. Fundamental Degree of consensus needed for major policy change a. Policy beliefs b. Resources socio-cultural values and social structure 4. Basic Constitutional structure (rules) EXTERNAL (SYSTEM) EVENTS 1. Changes in socio-economic conditions 2. Changes in public opinion 3. Changes in systemic governing coalition 4. Policy decisions and impacts from other subsystems W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education POLICY SUBSYSTEM Coalition A Policy Coalition B Brokers Strategy A1 re guidance instruments Constraints and Resources of Subsystem Actors a. Policy beliefs b. Resources Strategy B1 re guidance instruments Decisions by Governmental Authorities Institutional Rules, Resource Allocations, and Appointments Policy Outputs Policy Impacts (Sabatier, 1999, Figure 6.4) 4 3. Based on the conception of advocacy coalition, Sabatier constructs a advocacy coalition framework for policy implementation into three dimensions a. The exogenous factors: In connection to the top-down approach of policy implementation, Sabatier organizes the exogenous factors into two sets i. Relative stable parameters ii. External (system) events b. The intermediate factors: It includes another two sets of factors i. Constraints and resources of subsystem actors (advocacy coalitions) ii. Degree of consensus needed for major policy change c. The dynamics within the policy subsystem: Based on the bottom-up approach, the framework put strong emphasis on the strategies and conflicts played out by different advocacy coalitions found in the policy subsystem under study. This part of the framework consists of i. Identifying the major advocacy coalitions (about 3 to 4) at work in the policy subsystem ii. Analyzing strategies adopted by advocacy coalitions to construct the policy outcome in accordance with their own “belief systems”. iii. Analyzing the mediating process, through which the conflicts among coalition can be mitigated, compromised or even resolved by means of the work of the policy brokers. C. The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation 1. The concept of governance a. To understand the concept of governance, it is better to contrast it with the concept of government. “Governance…is accomplished through in ‘informal authority’ of diverse and flexible networks”, while “government…is carried out through hierarchies or specifically within administrations and by bureaucratic methods.” (Ball, 2012, P.3) In other words, the landscapes of public policy and public administration in the US and UK since 1980s, have witnessed a shift from “the government of a unitary state to governance in and by networks” (Bevir and Rhodes, 2003; Quoted in Ball, 2012, P. 2) b. In the field of policy making and implementation, the traditional bureaucratic model, which is characterized by clear and definite rules and regulations, consistent and routine procedures, and well-defined lines of authority and chains of commands, has been replaced to a substantial extent by the model commonly called “policy network.” 2. The concept of policy network: To have a comprehensive understanding of the concept of policy network, we can begin with the idea of network logics and its effects on human society. a. The constitution of the network logics i. “The Atom is the past. The symbol of science for the next century is the dynamical Net … Whereas the Atom represents clean simplicity, the Net channels the messy power of W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 5 complexity. …The only organization capable of nonprejudiced growth, or unguided learning is a network. All other typologies limited what can happen. A network swarm is all edges and therefore open ended any way you come at it. Indeed, the network is the least structured organization that can be said to have any structure at all. …In fact a plurality of truly divergent components can only remain coherent in a network. No other arrangement – chain, pyramid, tree, circle, hub – can contain ture diversity work as a whole.” (Kelly, 1995, p.25-27 quoted in Castells, 1996, note71, p. 61-62) ii. “Network can now be materially implemented, in all kinds of processes, and organizations, by newly available information technologies. Without them, the networking logic would be too cumbersome to implement. Yet this networking logic is needed to structure the unstructured while preserving flexibaility, since the unstructured is the driving force of innovation in human activity” (Castells, 1996, p. 62) b. The definitive features of network: The fluid structure of the network and its IT infrastructure have constituted numbers of features which is novel if not totally foreign to the bureaucratic structure of modern society. i. Flexibility: By flexibility, it refers to the state of affairs in which “not only processes are reversible, but organizations and institutions can be modified, and even fundamentally altered, by rearrangeing their components. What is distinctive to the configuration of the new technological paradigm is its ability to reconfigure, a decisive feature in a society characterized by constant change and organizational fluidity. ….Flexibility could be a liberating force, but also a repressive tendency if the rewriters of rules are always the powers that be. As Mulgan wrote: ‘Networks are created not just to communicate, but also to gain position, to outcommunicate.’” (Castells, 1996, p. 62) ii. Convergence: Built on the above-mentioned features of IT network, the network also equips with high degree of compatibility and convergeability, with other systems. iii. Mobility and autonomy: As informational technology and mass communication turn from “wired” to “wireless”, they have become much more mobile. IT and communication apparatuses are no longer confined or pinned down to a definite location. As a result, they have allowed their users to liberate from particular physical localities and even social institutions, such as families, workplaces, offices, and schools, etc. (Castell, 2008, Pp448-449) c. According to Castells analysis, two of the essential consequences that the advent of the IT paradigm and network logic brings to bear on human relationship are i. Space of flow: Manuel Castells (1996) underlines that one of the profound features brought about by the global-informational infrastructure is the separation of simultaneous social practices from physical contiguity, that is time-sharing social practices are no long embedded in locality of close proximity and/or within W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 6 finite boundary. As a result, the traditional notion of space of places has been transformed into space of flows. In informational network, such as the internet, "no place exists by itself, since the positions are defined by flows." There is practically no boundary, no concepts of center or periphery, no beginning or end. It is all but flows. ii. Timeless time: Castells also underlines that the global-Informational infrastructure has also transform the conception of time in human society. Time is no longer comprehended in terms of localities around the globe according to the international time-zones. Human activities around the global can be coordinated "simultaneously" in disregard of conception of local time, such as morning, evening, late at night, etc. Furthermore, with the aid of IT, the conventional linear, sequential, diachronic concepts of time has been disturbed. "Timing becoming synchronic inflate horizon, with no beginning, no end, no sequence." (Castells, 1996, p. 74) d. The concept of network society: As a result, the modern society that we are so familiar with and used to, i.e. a configuration of social institutions, such as economy, polity, culture, and even social identity, built on definite physical locality and duration in time, has dissolved if not evaporated. In its replacement is a set of social institutions that are organized around the logic of network, namely operated in the flow of space and timeless time. e. The concept of policy network: i. By policy network, it refers to non-governmental and/or quasi-governmental organizations, which are independent and autonomous from one another but are connected in terms of resource-exchanges, contracting-in or out, partnership, strategic alliances, etc. They would jointly and collaboratively deliver services and achieve objectives prescribed in public policies. (Ball, 2012, P. 1-12) ii. It has been conceived that policy network as a form of governance that can be located between the continuum of Hierarchy and Market. As a form of governance, it “is characterized by the plurality of autonomous actors, as they are found within markets, and the capacity to pursue collective goals through deliberately coordinated actions, which is one of the major elements of hierarchy.” (Raab and Kennis, 2007, 191) 3. The network governance and its effects a. The hybrid structure of the network governance: Stephen J. Ball summarizes his study of Networks, New Governance and Education in UK that “what is emerging here is a new hybrid form or mix of networks + bureaucracy + markets that is nonetheless fashioned in the shadow of hierarchy.” (Ball, 2012, P. 133) b. The operative principle of the network governance: Ball underlines that working underlying the emerging form of network governance is “the interplay or dialectic of performance management and deconcentration” (Ball, 2012, P. 133) It refers to mechanism of steering (in contrast to rolling) at a distance, such as policy W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 7 mechanism of output accountability, value for money, quality assurance inspection, performance auditing, etc. “This is the means of ‘governing through governance’―the state becomes a contractor, performance monitor, benchmarker and target setter, engaging in managing.” Ball, 2012, P. 133) As a result, the role of the in policy delivery has undergone “a shift from ‘directing bureaucracy’ to ‘managing networks’.” (Ball, 2012, P. 134) c. The foundational epistemology of the network governance: Ball points out that emergence from “the mix of market, hierarchies and network” in network governance is a new type of player in policy and service delivery, what he called the “new philanthropy”. By new philanthropy it refers to “the direct relation of ‘giving’ to ‘outcome’ and the direct involvement of givers in philanthropic action and policy community. …This new sensibilities of giving are based upon the increasing use of commercial and enterprise models of practice as a new generic form of philanthropic organization, practice and language.” (Ball, 2012, P. 49) As a result, in the domain of network governance, “public sector education, philanthropy and business are increasingly blurred and increasingly convergent in relation to a ‘foundational epistemology’―which is ‘pragmatic entrepreneurialsim’.” (Ball, 2012, P. 135) d. Etho-politics of responsible self-government: Ball further asserts that “new governance is a moral field in a dual sense. (i) There is a bottom-up morality expressed in form of charitable giving and hands-on philanthropy and CSR (corporate social responsibility)―a taking on of responsibility for social problems. ….(ii) There is also a top-down morality expressed and enacted―incitements to responsibility for yourself and others―in forms like volunteering participation in local voluntary association and mutualism.” (Ball, 2012, P. 135) “Together, these commitments and incitements constitute a very particular version of what Rose …calls ‘etho-politics’…. Self-government or mutual government replaces state government: ‘etho-politics concerns itself with self-techniques necessary for responsible self-government. Government, or ether governance, acts upon ‘the ethical formation and the ethical self management of individuals’ (Rose, 199, P. 475) as individual take on social responsibilities that were formerly the domain of the state.” (Ball, 2012, P. 136) e. In conclusion, Ball paraphrases Trainafillou that “‘we could broadly characterize network governance as the diverse governmental rationalities, technologies and norms that seek to govern by promoting the self-steering capacities of individuals and organizations.’” (Traintafillou, 2004, Quoted in Ball, 2012, P. 140) Furthermore, Ball reiterates that “the change we are describing here are situated in relation to a boarder set of practical techniques of government rthat have in part the aim and effect of producing new kinds of ‘active’ and responsible, entrepreneurial citizens and workers.” (Ball, 2012, P. 140) W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 8 D. Policy Implementation as Learning 1. "Since the 1990s, implementation researchers have increasingly come to see the problem of educational policy implementation as one of teacher learning." (Coburn & Stein, 2006, p. 25). Within the third generation of education-policy implementation, researches on policy learning and cognition have grown into one of the prominence school within the field. 2. At individual level, researches on teacher learning and cognition have revealed that as primary implementers of policy, teachers do not mechanically comply with policy directives but they would interpret and make sense of the objectives, measures, outcomes and consequences of the policy to be implemented. What researches on policy implementation and cognition revealed "is not simply that implementing agents choose to respond to policy but also what they understand themselves to be responding to. …The fundamental nature of cognition is that new information is always interpreted in light of what is already understood. An individual's prior knowledge and experience, including tacitly held expectations and beliefs about how the world work, serve as lens influencing what the individual notices in the environment and how the stimuli that are noticed are processed, encode, organized, and subsequently interpreted." (Spillane et al., 2006, p. 49) 3. At community level, recent researches on educational policy implementation also revealed that "sense-making is not a solo affair; an individual's situation or social context fundamentally shapes how human cognition affects policy implementation." Education-policy learning by definition as well as by nature takes place in institutional sitting, i.e. schools. In other words, ‘social agents' thinking and action is situated in institutional sectors that provide norms, rules, and definition of the environment that both constrain and enable action." (Spillane et al, 2006, p. 56) As a result, researches on professional community practice and learning community formation have become a prominent area of study in the field of education-policy implementation. (Odden, 1991; Honig, 2006) One of the important approaches to teacher learning as a professional community is Etienne Wenger’s theory of social learning theory (Wenger, 1998) To Wenger learning is not just a cognitive activity of information acquisition and processing undertaking by a single individual. By social learning, it emphasizes the social and interactive dimension of learning. As a result, learning is more than a process of information acquisition, it is a complex process consisting of a. lived experiences of sense making and meaning constructing; b. mutual engagement of practices of knowledge and skills and constituting standards of excellence of competence in a craft, a trade and a profession; c. built on the shared meanings and practice, a common culture, a community and lifeworld will emerge among fellow workers; d. members of the craft and profession will nurture a sense of belong and commitment to the trade and the community of practice, i.e. an identity. This social learning process can be represented as follows. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 9 4. At school-organization level, policy implementation represents a process of dissemination of policy imperatives, task specifications and working routines within the ranks and files of the implementing organization. As a result, organizations, school-organizations in particular have be studied as the learning organization. Among the proliferating approaches to learning organization, three of the more representative are outline as follows a. Ikujiro Nonaka’s Knowledge-Creation Organization i. Two dimensions of knowledge creation - Epistemological - Ontological ii. Two types of knowledge - Tacit knowledge - Explicit knowledge iii. Four models of knowledge conversion - Socialization: Sharing and creating tacit knowledge through direct experience; individual to individual - Externalization: Articulating tacit knowledge through dialogue and reflection; individual to group - Combination: Systemizing and applying explicit knowledge and information: group to organization - Internalization: Learning and acquiring new tacit knowledge in practice; organization to individual iv. Knowledge spiral - Field building - Dialogue - Linking explicit knowledge/networking - Learning by doing v. Spiral of organizational knowledge creation W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 10 b. Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline of the learning organization i. The five learning disciplines - Personal mastery - Mental models - Shared vision - Team learning - System thinking ii. System thinking - The fifth discipline iii. The Framework of learning organization - Implicate (generative order) - The Essence of the LO - The architecture of LO - The wheel of learning - Results c. Kenneth Leithwood’s theory of learning school i. Learning organization is defined as “a group of people pursuing common purpose (individual purposes as well) with a collective commitment to regularly weighing the value of those purpose, modifying them when makes sense, and continuously developing more effective and efficient ways of accomplishing those purpose.” (Leitrhwood & Aitken, 1995, p.63) ii. Five constituents of the framework of the learning organization - Stimulus for learning - Organizational-learning process - Out-of-conditions - School conditions - School leadership - Outcome E. New Directions in Education Policy Implementation Studies: Confronting Contingencies and Complexity 1. Having reviewed researches on implementation of education policy in the US since the 1960s, Meredith I. Honig suggests that a distinct approach to policy implementation research has constituted since the 1990s. These education policy implementation researchers shared a number of epistemological stances. a. These researchers “are less likely than those in past decades to seek universal truths about implementation. Rather, they aim to uncover how particular policies, people, and places interact to produce results and they seek to accumulate knowledge about these contingencies. …This orientation to uncovering contingencies―what I refer to …as confronting complexity―stems not from a lack of rigor or scientific―basis for educational research but rather from the basic the basic operational realities of complex systems in educational and many other arenas.” (Honig, 2006, P. 20) b. These “researchers increasingly reflects the orientation that variation in implementation is not a problem to be avoided but part and parcel of the basic operation of complex system; variation W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 11 should be better understood and harnessed to enhance the ‘capacity of program participants to produce desired results’ This view stems in part from contemporary research on student and teacher learning that suggests one size does not fit all when it comes to educational improvement.” (Honig, 2006, P. 21) c. “This orientation also reflects relatively recent education policy implementation findings about sense making, interpretation, and learning as unavoidable dimensions of implementation process.” (Honig, 2006, P. 21) d. This research orientation “is more deeply theoretical” in a sense that it “aims not to develop a universal theory about implementation as an overall enterprise but to use theory to illuminate how particular dimensions of policies, people, and places come together to shape how implementation unfold.” (Honi, 2006, P. 21) e. Within this research orientation, “qualitative research design and method have become important sources of knowledge. …IN particular, strategic qualitative cases for implementation―cases that provide special opportunities to build knowledge about little understood and often complex phenomena―have long informed implementation in other field and seem to becoming more standard fare within education.” (Honig, 2006, P. 22) 2. In light of these recent developments in the field, Honig proposes a three-dimension model for education policy implementation researches. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 12 E. From Policy Implementation to Policy Enactment: How Schools Do Policy Stephen J. Ball and his colleagues published their most recent research on education policy implementation in 2011 in a book entitled How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools. The work attempt to go beyond the traditional research orientation of policy implementation, instead they call the process “policy enactment”. More importantly, Ball and his colleagues attempt to substantiate Foucalt’s of discourse, power, and subject within the policy process of enactment (and implementation) in the school contexts of UK. 1. Concept of policy enactment: Ball et al. begin their book with a distinction between policy implementation studies and their policy enactment studies. a. Policy implementation: Ball et al. indicate traditional policy implementation studies that “explore how policies are put into practice talk of ‘implementation’ which is generally seen either as ‘top down’ or ‘bottom up’ process of making policy work, and these studies ‘stress the demarcation between policy and implementation.’ (Grantham, 2001: 854)” (Ball, 2012, P. 6) Furthermore, they underline that these “policy implementation studies conceive of the school itself as a somewhat homogenous and de-contextualised organization that is an undifferentiated ‘whole’ into which various policies are slipped or filtered into place.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 5) b. Policy enactment: Ball et al. assert, “In contrast, we see policy enactment as a dynamic and non-linear aspect of the whole complex that make up the policy process, of which policy in school is just one part.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 6) Ball et al. has highlighted that this complex, dynamic and non-linear process is made up of i. re-contextualization process, ii. interpretation process, iii. translation process, and iv. transforming policy into policy work in policy actors 2. Policy re-contextualization: a. The first conceptual unit in Ball et al.’s theory of policy enactment is the policy context. Ball et al. underline that the major of education policy studies have been conducted in “de-contextualized” orientation. These studies more or least aim at constituting universal and generic policy measures, which can be implemented to most if not all schools. Ball et al. indicate that “research texts in education policy rarely convey any sense of the built environment from which the ‘data’ are elicited or the financial or human resources available―policy is dematerialized (Ball et al., 2012, P. 20) as well as de-contextualized. b. In contrast to this research orientation, Ball et al. emphasize that “context is mediating factor in the enactment work done in schools ―and it is unique to each school, however similar they may initially seem to be. In the course of the fieldwork, we have become alerted to the prominence of context in many case study schools’ policy W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 13 decision and activities.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 40) c. More specifically, Ball et al. assert that “Policy creates context, but context also precedes policy.” (Ball, 2012, P. 19) Ball et al. further specify the contextual differences found in their case study schools as follows. “Policies enter different resource environments; schools have particular histories, buildings and infrastructures, staff profiles, leadership experiences, budgetary situations and teaching and learning challenges (e.g. proportions of children with special educational need (SEN), English as an additional language (EAL), behavioural difficulties, ‘disabilities’ and social and economic ‘deprivations’) and the demands of context interaction. School differ in their student intake, school ethos and culture, they engage with local authorities and experience pressures from league tables and judgements made by national bodies such as Ofsted.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 19) d. Accordingly, Ball et al. have synthesized the “contextual dimension of policy enactment as follows 3. Policy interpretation: IT has been well documented in studies on education reform in recent decades that teachers as sensible and educated professionals, they will and have to “make sense” of the policy texts and mandates before they enact them, i.e. incorporate them into their role performances and even daily classroom routines. a. Concept of policy interpretation: “Interpretation is an initial reading, a making sense of policy―what does this text mean to us? What do we have to do? De we have to do anything? It is a political and substantive reading―a ‘decoding’ which is both retrospective and prospective.” (Ball, 2012, P. 41) b. Situated interpretation: Furthermore, this acts of reading, decoding and interpreting are “done in relation to the culture and history of the institution and the policy biographies of the key actors. It is a process of meaning-making which is related the smaller to the bigger picture; that is, institutional priorities and possibilities to political necessities. These situated interpretations are set over and against what else is in play, what consequences might ensure from responding or not responding.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 43-44) c. Articulation and authorization of interpretation: Policy interpretations are not individual acts within the bureaucratic contexts of schools. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 14 “The authoritative and authorial interpretations” of particular policy text have to be formally articulated in staff meetings, briefing sessions, work group discussions, written guidelines and task specifications. As a result, these “articulation and authorization” will “make something into a priority, assign it a value, high or low.” (p. 44-45) Hence, interpretation is an institutional political process.” (P. 45) d. Formation of Interpretive communities: These situated and institutionalized interpretations of policy texts in schools are not consensually and equally shared among teachers and other staffs within a school. It is because these policy interpreters are hierarchically positioned within the power context of a school. They will decode and interpret policy text with their primary concerns, vested interests, in short within their own “meaning contexts”. As a result, interpreters sharing similar positions or situations may and will share similar interpretations and form specific interpretive communities. 4. Policy translation: The third conceptual unit of the policy enactment theory is translation. As Ball et al. suggest “policy texts “cannot simply be implemented! They have to be translated from text to action―put into ‘practice―in relation to history and to contexts, with the resources available. (Ball et al., 2012, P. 3) a. Tactics of translation: Ball et al. reveal in their findings that translation of policy text and its interpreted meanings into school and classroom practice is “an iterative process” makes up of sequence of complex “tactics.” They “include talk, meetings, plans, events, learning walks, as well as producing artefacts and borrowing ideas and practices from other schools, purchasing and drawing on commercial materials and official websites, and being supported by LA advisors.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 45) b. Translation in mandated routines: Policy translation can also take the form of imperatives. In Ball et al.’s case study schools in UK, it takes the forms of “open class observation”, “peer observation” or “observation week”. Ball et al. underlines that “observation is a tactic of policy translation, an opening up of practice to change, a technique of power enacted by teachers one upon the other―’a marvelous machine’ (Foucault, 1979,:202) ―and a source of evidence of policy activity.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 46) c. The outcome of translation: From these tactics and imperatives of policy translation, “the language of policy is translated into language of practice, words into action, abstraction into inactive processes. Moreover, “translation is simultaneously a process of invention and compliance. As teachers engage with policy and bring their creativity to bear on its enactment, they are also captured by it. They change it, in some ways, and it changes tem.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 48) 5. Policy actors: Ball et al. point out that “our data indicates very clearly that actors in schools are positioned differently and take up different positions in relation to policy.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 49) These positioned policy actors have rendered different interpretation and translation to a particular policy and as a result have brought about different “policy W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 15 work”. Ball et al. have categorized eight types of policy actors and policy work from their data. They are as follows. (Ball et al., 2012, Table 3.1, P. 49) F. Policy actors Policy work Narrators Interpretation, selection and enforcement of meanings Entrepreneurs Advocacy, creativity and integration Outsiders Entrepreneurship, partnership, and monitoring Transactors Accounting, reporting, monitoring/supporting, facilitating Enthusiasts Investment, creativity, satisfaction and career Translators Production of texts, artifacts and events Critics Union representatives: monitoring of management, maintaining counter-discourse Receivers Coping, defending and dependency Policy Subjects: How Policy “Do” Schools, Teachers and Students Stephen J. Ball and his colleagues’ book, How Schools Do Policy, has not only revealed how schools and their teachers interpret, translate and enact education policies; it has also appled Michel Foucault’s conception of discourse, power, subject and panopticism to reveal how policy “do” (subjugate) schools, teachers and students. 1. Foucault’s concept of power and subject: In an essay entitled “The Subject and Power” (1982) Foucault reflect on his work on power by underlining that a. “I would like to say, first of all, what has been the goal of my work during the last twenty years. It has not been to analyze the phenomena of power, nor to elaborate the foundations of such an analysis. My objective, instead, has been to create a history of the different mode by which, in our culture, human beings are made subjects... Thus it is not power, but the subject, which is the general them of my research.” (1982, 208-209) b. “My work has dealt with three modes of objectification which transform human being into subjects.” (1982, p. 208) i. “The first of the modes of inquiry which try to give themselves the status of sciences for example, - the objectification of the speaking subject in grammaire generale, philology and linguistics;.... - the objectification of the productive subject, the subject who labors, in the analysis of wealth and economics;..... - the objectification of the sheer fact of being alive in natural history and biology.” (p. 208) (The most representative work is The Order of Things: An W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 16 Archaeology of Human Sciences, 1966) ii. “In the second part of my work, I have studied the objectivizing of the subject in what I shall call ‘dividing practices’. ...Examples are the mad and the sane, the sick and the healthy, the criminals and the ‘good boys.” (p. 208) (The representative works are Madness and civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, 1961; The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perspective, 1963; Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 1975) iii. “Finally, I have sought to study...the way a human being turns him or herself into a subject. ...I have chosen the domain of sexuality - how men have learn to recognize themselves as subjects of ‘sexuality’.” (p. 208) (History of Sexuality, vol. 1-3, 1982-1-84 are of course the representative works) 2. Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power and Panopticism a. Disciplinary power: In his book entitled Discipline and Punish: The Birth of Prison (1977/75), Foucault reveals how power with its technique and technology has turn humans into manipulatable, useful and docile bodies. i. He asserts, “In every society, the body was in the grip of very strict power, which imposed on it constraints, prohibition or obligations.” “Docility …joins the analyzable body (intelligible body) with the manipulatable body (useful body).” (1979/75, p. 136) ii. Foucault further specifies the techniques of power which discipline human body into submission and docility as disciplinary power. It refers to the techniques “which made possible the meticulous control of the operations of body, which assured the constant subjection of its forces and imposed upon then a relation of docility-utility.” (1979/75, p. 137) And one of the exemplar of such technology of disciplinary power is “panopticism” b. Panopticism: Foucault’s concept of panopticism refers to a form of technology of disciplinary power which creates a situation in which its subjects are in constant and unverifiable surveillance that they are forced to self-disciplined and complete compliance. Foucault has specified this technology as follows. i. “Bentham's Panopticon is the architectural figure ….. We know the principle on which is was based: at the periphery, an annular building; at the centre, a tower; this tower is pierced with wide windows that open onto the inner side of the ring; peripheric building is divided into cells, each of which extends the whole width of the building; they have two windows, one on the inside, corresponding to the windows of the tower; the other, on the outside, allows the light to cross the cell from one end to the other. All that is needed, then is to place a supervisor in the central tower and to shut up in each cell a madman, a patient, a condemned man a worker or a schoolboys. By the effect of blacklighting, one can observe from the tower, standing out W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 17 precisely against the light, the small captive showers in the cells of the periphery. …. Visibility is a trap." (Foucault, 1977, p. 200) ii. “The major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. So to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action; that the perfection of power should tend to render its actual exercise unnecessary; that is architectural apparatus should be a machine for creating and sustaining a power relation independent of the person who exercises it; in short, that the inmate should be caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers.” (, p. 201) iii. The Panopticon has “laid down the principle that power should be visible and unverifiable. Visible: the inmate will constantly have before his eyes the tall outline of the central tower from which he is spied upon. Unverifiable: the inmate must never know whether he is being looked at at any one moment; but must be sure that he may always be so.” (, p.201) 3. Policy subjects under the “standard policy” in UK schools: a. In Chapter Six of the book, which is entitled Policy Subjects, Ball et al. underline that they have used “ideas drawn from Foucault’s Discipline and Punish to think about some of the ways in which policies are rendered into practices through a complex of techniques, procedures and artefacts ― or ‘force relations’. Here teachers are both the enactors of techniques, which are intended to make students visible and productive, and are themselves enmeshed within a disciplinary programme of visibility and production, a ‘dense network of vigilent and multi-directional gaze’ (Hoffman, 2010: 31). …Here the teacher is actor and object and subject, caught up in a marvellous machinery of policy.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 72) b. The “marvellous machinery of policy” Ball et al. refers to are series of policy measures implemented in UK schools intended to raise the standards of UK students in public examinations as well as in international studies of student assessments on achievements. Ball et al. asserts that these series policy texts have constituted a “delivery chain” of the “standard policy” in UK school system. c. Subjugating teachers, students and schools: Ball et al. have revealed from their data that the machinery of policy or in Foucaultian terms technique of disciplinary power has subjugated teachers, students and schools in numbers of ways. i. Focus on standard: Ball et al. underline that “in almost all of the interviews at all the schools, ‘standards’ are identified as the major priority. ….The word ‘focus’ is used repeatedly in interviews to describe the orientation of schools and staff tot eh question of standards at all levels.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 76-77) These repeated and consensual emphases on ‘focus’ signify that UK teachers are brought to the situation of “bringing a lens to bear, a close-up view, a point of concentration, bring things into visibility.” (Ball, 2012, P. 77). W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 18 ii. Actualization into actions and practices: These verbal and textual emphases on standard are further required to be substantiated into “precise, organized and efficient action. It is also used in relation to different subjects and objects. That is, teachers, students and schools, and pedagogies, procedures, performances, data and initiatives, all of these objects and subjects are to be ‘focused’ on.” (Ball et al., 2012, P. 77) As a result, all personnel and their practices in schools are brought to bear under the disciplinary power of the standard policy. iii. Objectification the subjects: Based on their practices and performances, teachers, students and schools are then “objectified” into categories and strata. For example, “students are objectified as talented, borderline, underachieving, irredeemable, etc.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 78) Teachers may also be objectified as “value-adding” or non-value-adding teachers. And schools will be labeled as “failing schools” and put against the rankings in “school league table. Together they have been objectified into subjects of the standard policy. iv. The Obviousness and necessity of the standard policy: Ball et al. have revealed that “most teachers in our study appeared to be thoroughly ‘enfolded’ into and part of the calculated technologies of performance. Its ‘obviousness’ needs no explanation.” (Ball et al. 2012, P. 79) Ball et al. underline that “the rhetoric of necessity legitimates, generates and naturalizes a varied and complex set of practices and values, which colonise a great deal of school activities and teacher-student interaction.” (ball et al., Ball, et al., 2012, P. 79) Additional Reference Castells, Maneul (1996) The Rise of Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell. Foucault, Michel (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin Books. Foucault, Michel (1982) “The Subject and Power” Pp. 208-226. In H.L. Dreyfus and P. Rabinow. Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, 2nd Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 19