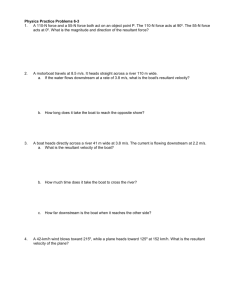

Final Senior Design II Documentation

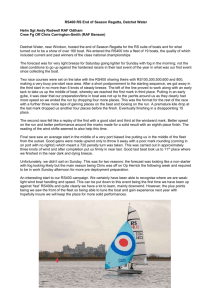

advertisement