Desegregation of Detroit Public Schools

advertisement

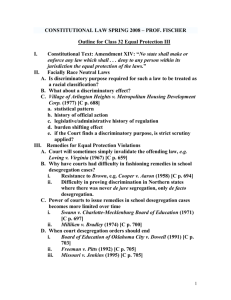

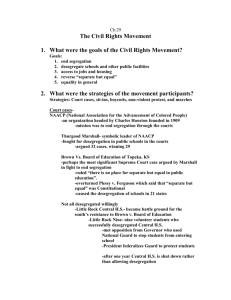

Desegregation of Detroit Public Schools Milliken v. Bradley LaVonne Meyer, Mary Neal, and Michael Hoffman Racial Tension and White Flight In ‘40, 90.8% of Detroit residents were White By ‘74, 71.5% of Detroit’s student population was African American. Between 1950 and 1970, the city lost 338,000 residents metropolitan region gained almost 1.4 million residents. 12th Street Riot of 1967 Riot started on July 23, 2007 and lasted for five days National guard made 7,200 arrests, left 43 dead, and 467 injured. Over 2000 buildings burned down 12th Street later becomes Rosa Parks Blvd. Mayor Coleman Young Racism is like high blood pressure – the person who has it doesn’t know he has it until he drops over with a goddamn stroke. There are no symptoms of racism. The victim of racism is in a much better position to tell you whether or not you’re racist than you are. I issue a warning to all those pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers: It’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road! And I don’t give a damn if they are black or white, of if they where Superfly suits of blue uniforms with silver badges. Hit the road. School Desegregation Through 2nd Half of 20th Century June ’50 Heman Sweatt admitted to UofT Law School. May ’54 Brown v. Board of Ed. Decided Sept. ’57 Little Rock Central High School Sept. ’61 District court dismisses Highland Park desegregation case Oct. ’62 Riots at University of Mississippi over first black student July ’64 Johnson signs Civil Rights Act Early ’69 Oakland County NAACP files suit complaining that Pontiac schools are deliberately segregated School Desegregation Through 2nd Half of 20th Century (cont.) Feb. ’70 Court finds Pontiac intentionally violated 14th amendment but school officials appeal and delay busing order. April ’70 Detroit school board alters attendance boundaries of 12 high schools Aug. ’70 Bradley v. Milliken challenges April ’70 plan April ’71 busing authorized to desegregate public schools in North Carolina July ’71 85 school districts added as defendants in Milliken I Aug. ’71 Pontiac ordered to desegregate and the KKK blows up the buses that Pontiac needs to integrate. Sept. ’71 Dist. Ct. rules on Milliken I School Desegregation Through 2nd Half of 20th Century (cont.) June ’74 School desegregation in Boston triggers rioting July ’74 Milliken I reversed in Sup. Ct. Nov. ’75 DeMascio orders “modest” desegregation plan Jan. ’76 22,000 children board buses and desegregation of Detroit begins June ’78 Sup. Ct. declares colleges can use race as a factor in admissions School Desegregation Through 2nd Half of 20th Century (cont.) Aug. ’81 Congress repeals the federal law that funded school desegregation efforts 1981 Detroit expands busing and Ferndale begins it. 1988 Fed. Dist. Ct. relinquishes oversight of city schools desegregation June ’95 Sup. Ct. ends a desegregation program in Kansas City, Missouri June ’03 Sup. Ct. rules that UofM can favor minorities in admissions. April 17th Plan In 1970, DBE voluntarily began implementing desegregation plan Michigan legislature blocked integration Act 48 of Public Acts of 197 Prescribed “free choice” and “neighborhood schools Delayed transportation funding for blacks but not for whites State Transportation Aid Act expressly prohibited allocation of funds for racial balancing DBE’s “optional attendance zones” Nathanial R. Jones 1956-1959 Executive Director, Fair Employment Practices Commission, City of Youngstown, Ohio 1960-1967 Assistant United States Attorney, Northern District of Ohio at Cleveland 1967-1968 Assistant General Counsel, National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission) 1969-1979 General Counsel, NAACP Paul R. Dimond With Jones on the brief for Bradley 1975-1976 Director, Lawyer's Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Published “Beyond Busing” in 1985 Now works for Miller Canfield in Ann Arbor and does mainly real estate. Response to Ineffective Plan: Milliken begins Class action suit, named for Ronald and Richard Bradley, brought by their mother, Verda Bradley against defendants including: for their Mich. Governer (Milliken) Mich. Attorney General Superintendent of Public Instruction State Treasurer Mich. Board of Educ. Det. Board of Educ. Det.’s current and former Superintendents policies, actions, and inactions contributing to de jure segregation De Facto v De Jure Segregation De facto segregation due to factors other than official policies and decisions De jure segregation is triggered by officials’ policies or decisions that either create or maintain racial segregation. School Desegregation Caselaw: Pre-Milliken Time for “Deliberate Speed” has passed, Immediate Remedies Needed “The burden on a school board today is to come forward with a plan that promises realistically to work, and promises realistically to work now.” Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (U.S. 1968) Prior Caselaw (cont.) Remedy Based on Equitable Principles “In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the courts will be guided by equitable principles. ... At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in making the transition to school systems operated in accordance with the constitutional principles” Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294, 299-300 (1955) “[A] school desegregation case does not differ fundamentally from other cases involving the framing of equitable remedies to repair the denial of a constitutional right. The task is to correct, by a balancing of the individual and collective interests, the condition that offends the Constitution.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971) Prior Caselaw (cont.) Appropriate for District Court to Prescribe, Oversee Desegregation Plan, no Clear Limit on this Power “Once a right and a violation have been shown, the scope of a district court's equitable powers to remedy past wrongs is broad, for breadth and flexibility are inherent in equitable remedies.” Swann v. CharlotteMecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 16 (U.S. 1971) “The remedy for such segregation may be administratively awkward, inconvenient, and even bizarre in some situations and may impose burdens on some...No fixed or even substantially fixed guidelines can be established as to how far a court can go, but it must be recognized that there are limits.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1971) “The scope of permissible transportation of students as an implement of a remedial decree has never been defined by this Court and by the very nature of the problem it cannot be defined with precision.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1971) Prior Caselaw (cont.) Scope of Desegregation Plan may Include such Measures as Teacher Reassigmnet, Re-districting of Re-zoning, Transportation of Students, Remedial Coursework “[District Courts may] consider problems related to administration, arising from the physical condition of the school plant, the school transportation system, personnel, revision of school districts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a system of determining admission to the public schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regulations which may be necessary[.]” Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294, 300-301 (1955) “[Defendant School Board] argues that the Constitution prohibits district courts from using their equity power to order assignment of teachers to achieve a particular degree of faculty desegregation. We reject that contention. Swann v. CharlotteMecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1971) “[O]ne of the principal tools employed by school planners and by courts to break up the dual school system has been a frank -- and sometimes drastic -- gerrymandering of school districts and attendance zones. More often than not, these zones are neither compact nor contiguous; indeed they may be on opposite ends of the city. As an interim corrective measure, this cannot be said to be beyond the broad remedial powers of a court. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1971) Prior Caselaw (cont.) No Requirement for Specific Racial Balance in each School, but Single-race School raises Presumption of Discrimination “Where the school authority's proposed plan for conversion from a dual to a unitary system contemplates the continued existence of some schools that are all or predominately of one race, they have the burden of showing that such school assignments are genuinely nondiscriminatory. The court should scrutinize such schools, and the burden upon the school authorities will be to satisfy the court that their racial composition is not the result of present or past discriminatory action on their part.” Swann v. CharlotteMecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1971) “The constitutional command to desegregate schools does not mean that every school in every community must always reflect the racial composition of the school system as a whole.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1971) Judicial Involvement Risk of High Profile Desegregation Case Judge in similar case in Richmond, VA house was bombed Special master in Dayton, OH case shot In Detroit Rioting, block busting, and public scorn of judges Heightened security Special entrance for judges and clerks Federal Marshal protection for judges and families Colleagues believe stress of case killed Roth Judicial Involvement (cont.) High Maintenance of Milliken Case DeMascio employed two clerks for two-year terms at any given time. One was assigned full time to Milliken throughout course of case DeMascio calls School Board and Teachers' Union into quarters for status hearing on contract negotiations out of concern that imminent strike could scuttle portions of proposed remedy, orders them to meet daily to resolve issue Liaison appointed to meet with heads of local colleges and universities to solicit their involvement in remedy for public schools Court staff met with business and community leaders to encourage their support of desegregation efforts Three desegregation experts appointed to serve as officers of the court DeMascio denies plaintiff's motion that he recuse self after remand from 6th Cir., citing both difficulty of transfer such a labor intensive case to a new judge, and lack of bias or inappropriate actions on his part. Surpreme Court Composition Chief Justice Burger: Majority Stewart: Concurring Opinion Douglas: Dissent White: Dissent Joined by Stewart, Blackmun, Powell, and Renquist Joined by Douglas, Brennan, Marshall Marshall: Dissent Joined by Douglass, Brennan, White Constitutional Issue of Milliken I Milliken and the 14th Amendment, § 1 The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, § 1, reads in part: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Burger on Constitutional Issues Majority found no violations of 14th amendment in outlying districts “[N]o state law is above the Constitution. School district lines and the present laws with respect to local control are not sacrosanct, and if they conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment, federal courts have a duty to prescribe appropriate remedies.” Although record contained evidence of de jure segregation, an intradistrict remedy would be “wholly impermissible [and] based on a standard not hinted at in Brown I and II or any holding of this Court.” Stewart on Constitutional Issues Upheld Sixth Circuit’s finding of Equal Protection Clause violation. However, Stewart did not believe issue was of substantial constitutional law as much as appropriate exercise of federal equity jurisdiction. “the mere fact of different racial compositions in contiguous districts does not itself imply or constitute a violation of the Equal Protection Clause in the absence of a showing that such disparity was imposed, fostered, or encouraged by the state or its political subdivisions…” Douglas on Constitutional Issues Central issue is “whether the State’s use of various devices that end up with black schools and white schools brought the Equal Protection Clause into effect” Can State “… wash its hands of its own creations”? White on Constitutional Issues Invokes concern of a return to pre-Plessy acceptance of separate and inferior black schools and potential nullification of Brown Believes the majority opinion allows “the state of Michigan, the entity at which the Fourteenth Amendment is directed, [to] successfully insulate itself from its duty to provide effective desegregation remedies by vesting sufficient power over its public schools to the local school districts.” Marshall on Constitutional Issues “[H]owever imbedded old ways, however ingrained old prejudices, this Court has not been diverted from its appointed task of making a ‘living truth’ of our constitutional idea of equal justice under law.” – quoting Cooper Actions by State agency are actions by the State. System deliberately constructed to maintain segregation Admits desegregation poses challenge, but insists upholding equal protection is of prime importance. Local Control: Burger “No single tradition in public education is more deeply rooted than local control over the operation of schools; local autonomy has long been thought essential both to the maintenance of community concern and support for public schools and to quality of the educational process.” Local Control: Dissents Douglas notes that Michigan’s education system is actually a unitary one White argued that the state’s attempt to dismantle the April 7 Plan in 1971 proved the state maintained control Marshall: “Michigan, unlike some other States, operates a single statewide system of education… the majority’s emphasis on local government control and local autonomy of school districts in Michigan will come as a surprise to those with any familiarity with that State’s system of education.” Limitations on Milliken I Remedies Flaws of Metropolitan Remedy Sole purpose of interdistrict as opposed to single-district remedy was to achieve particular racial balance, however such balance not required Interdistrict remedy “could disrupt and alter the structure of public education” Oversight of interdistrict remedy would make District Court into “a de facto 'legislative authority'” and a “'school superintendent' for the entire area” Burden of remedy shall not be imposed on jurisdictions not shown to have contributed to constitutional violation Remedy should be limited to that necessary to restore victims to position they would have enjoyed absent demonstrated constitutional violation. Milliken I Remedy Limitations (cont.) Prospective Limitations on Remedies by District Courts To include multiple districts in a remedy, plaintiffs must show Constitutional violation by each of the districts to be included in remedy or discriminatory intent in drawing district boundaries Milliken I Remedy Limitations (cont.) Limits on the Limitations Only limits judicial remedies, not acts by legislature, school boards, or other government bodies Does not preclude interdistrict remedy, but puts higher burden on plaintiffs to show such remedy appropriate Constitutional Issues in Milliken II Court rejects claims that sharing cost of programs between local school boards and State does not violate Amendments X or XI Single-District Remedy on Remand Plaintiffs and Board of Education both Submit Plans Plaintiffs' plan rejected by District Court relies almost solely on transportation, would require some 900 buses geared towards achieving most even distribution of white/black students transports children even from desegregated schools to achieve racial balance elsewhere, transports from majority black school to majority black to achieve marginal change in racial balance Most schools will remain more than 80% black Single-District Remedy (cont.) Board’s plan more comprehensive, forms basis for District Court remedy with alterations Transportation lesser component Some 300 buses would still be required three inner-city regions which are more than 90% black not included in transportation plan Additional components of Board plan include Teacher reassignment Training of teachers, counselors Redrawing school zones, redesigning “feeder” system for middle schools and high schools Single-District Remedy (cont.) Detailed, Comprehensive Remedy from District Court Designed to Preserve Educational Integrity Transportation disfavored means of achieving desegregation, but included with limitations re-zoning should be exhausted before resorting to busing, “region” lines should not hinder rezoning no students should be bused to/from already desegregated schools, students should not be bused from one majority black school to another when pairing schools for desegregation, distances should be minimized; already desegregated schools should not be paired grade structure should be uniform across district 30-55% black considered integrated; no school should be more than 70% white, but majority black school OK where further desegregation impractical If school nearly integrated, “satellite zones” preferred over busing, where students must be bused to elementary school, those students should be able to go to neighborhood middle school. Transportation burden between adjacent regions should be equalized No middle school shall be more than 50% white, middle schools may be either zoned, open, or magnet Single-District Remedy (cont.) Remedial skills program instituted to boost achievement In-service training for teachers, administrators through Wayne State University Vo-Tech High Schools assimilated into magnet program, will expand opportunities, open skilled trades to blacks, new sites for Vo-Tech HS will be chosen to achieve maximum integration Race-blind testing Establish clear student rights and responsibilities for prevention of violence, discrimination by staff or students Outreach to parents, focus on school-community relations Counseling and career guidance Integration of Co-Curricular activities Bilingual/Multiethnic studies programs Faculty reassignment Single District Remedy (cont.) Does this remedy make the District Court any less of “a de facto ‘legislative authority’” and a “’school superintendent’ for the entire area?” School Desegregation Caselaw: Post-Milliken Surpreme Court has not Considered a Metropolitan Desegregation case Plaintiffs in Milliken I given leave to amend complaint to show evidence of constitutional violation by suburban districts but never did so Any further actions against the districts conditioned on Plaintiffs (really NAACP) paying cost of initial appeal for those districts. NAACP chose to focus efforts elsewhere, never paid costs of amended complaint. Suburban districts did not press for payment, probably content to forgo money and escape further litigation. Subsequent cases involving interdistrict desegregation denied certiorari or affirmed without opinion Subsequent Caselaw (cont.) Lower Courts have Approved Interdistrict Remedies which meet the Milliken I Burden of Showing Interdistrict Constitutional Violations Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board of Education, 510 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir. 1974) “A vital distinction between Milliken and the present cases is that in the former there was no evidence that the outlying school districts had committed acts of de jure segregation or that they were operation dual school systems. Exactly the opposite is true here” A crucial difference between the present cases and Milliken is that school district lines in Kentucky have been ignored in the past for the purpose of aiding and implementing continued segregation.” Also, interdistrict remedy simpler because region at issue smaller, less populous. “In Kentucky, the county is established as the basic educational unit of the state, … the state legislature has referred to the boundaries of school districts as “artificially drawn school district lines.” …[and T]he merger or consolidation in that state could be effectuated under the express provisions of a Kentucky statute.” Subsequent Caselaw (cont.) Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del. 1975) aff’d per curiam 423 U.S. 963 (1975) “The record in this case is replete with evidence that racial balance in housing is integrally related to racial balance in the public schools” Evidence of interdistrict violations in 1950s when “black schools in Wilmington under the de jure system were schools for black children from throughout New Castle County” and also “suburban white children crossed district lines to attend “white” school sin Wilmington” Post-Brown, white families left Wilmington for suburban New Castle County and the Wilmington City schools were left predominantly black “Governmental authorities condoned and encouraged discrimination in the private housing market and provided public housing almost exclusively within… Wilmington. The specific effect of these policies was to restrict the availability of… housing to blacks in suburban New Castle County… This conduct constitutes segregation action with inter-district effects under Milliken.” Enrollment policies in Wilmington led to disproportionate number of black students in schools in majority white neighborhoods, exacerbating “white flight.” Exclusion of City of Wilmington from legislative act permitting consolidation of districts by State School Board violated Equal Protection Clause Detroit Recently: Oft-Cited Model of Urban Decay 2000 population is 951,270 compared to 1,849,568 in 1950 220 Detroit Public Schools with 116,000 students In 2000, just under 83% of Detroit residents were African American 70% of Metro Detroit’s African Americans live in Detroit 34.5% of Detroiters under the age of 18 live below the poverty line In contrast, Neighboring Oakland County is the 4th wealthiest county in the nation.