Comparison of rhythm of Jamaican Creole

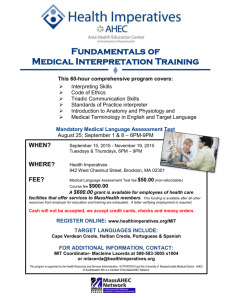

advertisement

Introduction A comparison of rhythms in Jamaican Creole speech and reggae music Project’s long term goals We chose to compare the rhythmic patterns of Jamaican Creole speech to Jamaican reggae music, and to contrast these rhythmic characteristics to those of African American English and jazz music (one of the most genuinely “American” musical genres). Christina G. Rozek ’15, Angela C. Carpenter (Linguistics), Andrea G. Levitt (French & Linguistics) Cognitive and Linguistic Sciences Summer 2013 This summer We completed the analysis of all Jamaican Creole speech samples and partially analyzed the reggae music samples. Rhythm in speech and music Rhythm in speech: “Patterns of timing and accentuation that characterize the flow of syllables in sentences.” (Patel, p. 96) Rhythm in music: Namely, “A pattern repeating regularly in time,” (Patel, p. 96) but in our case, a pattern of long and short notes. Types of speech rhythm Hypothesis Continuing research Jamaican Creole is a syllable-timed language because of its reduced consonant clusters and pattern of limited vowel reduction. We will finish our analysis of the reggae music and calculate an nPVI for the durations of the notes. We will compare it to the nPVI that we calculated for Jamaican Creole speech. Syllable-timed French is a syllable-timed language Syllables occur at regular intervals Little unstressed syllable-reduction Jamaican Creole speech will share rhythmic characteristics with reggae music. We plan to use the Jamaican Creole and reggae music methods also to compare Black American English and instrumental jazz music. Stress-timed English is a stress-timed language Stressed syllables appear to occur at regular intervals Unstressed syllables are reduced Method Mora-timed Japanese is a mora-timed language A consonant-vowel syllable, or just individual consonants and vowels occur at regular intervals. One way to measure these differences is by using nPVI (normalized Pairwise Variability Index) Jamaican Creole Jamaican Creole, also called “patois,” is a standard creole that arose from a pidgin. Pidgin: “A simple but rule-governed language developed for communication among speakers of mutually unintelligible languages, often based on one of those languages called the lexifier language.” (Fromkin, Rodman, & Hyams, p. 556) Creole: “A language that begins as a pidgin and eventually becomes the first language of a speech community through its being learned by children.” (Fromkin, Rodman, & Hyams, p. 542) Reggae Many people are familiar with reggae through the work of Bob Marley, one of the founding influences on the genre. However, since the rise of electronic sound mixing technology, an industry has developed of what are called “producers.” Producers create instrumental pieces with melodic lines (called “riddims”), and sell them to singers who fit their lyrics to the producer’s melody. nPVI (normalized Pairwise Variability Index) Participants Five contemporary Jamaican producers Materials Speech: We found interviews of producers on YouTube, using natural speech samples as opposed to scripted speech. Much of the research done comparing the rhythms of music and speech from a culture rely on analyzing participants’ productions of scripted text and measuring the lengths of notes in sheet music, so our approach using natural speech and recorded music is rather different. Music: We selected two riddims from each Jamaican producer. These were the original versions of the riddims, not the ones that had been recorded over (found on YouTube and other internet sources). Analysis Speech: We selected 20-30 phrases from each producer. Each phrase was preceded by a 50-60ms pause, and we also relied on intonation patterns and semantic content, rather than just pauses, to help us make divisions between phrases. For each phrase we provided a translation from Jamaican Creole into Standard American English, and for each sound we indicated whether it was a vowel or consonant and we provided a phonetic transcription. 2.1 2.1 1 2.1 2.1 1 1 Large contrast nPVI = 71 1 Small contrast nPVI = 24 Questions or comments concerning the project should be addressed to: Angela C. Carpenter, Department of Cognitive and Linguistic Sciences Wellesley College, 106 Central St., Wellesley, MA 02481 E-MAIL: acarpent@wellesley.edu 50.5 47.7 45.5 41.7 Jamaican Creole is a syllable-timed language. Jamaican Creole’s rhythm is a blend of English (stress timed) and West African languages (syllable timed) and has retained the West African syllable-timing stress pattern. The stress pattern in Jamaican Creole produces an nPVI more closely related to French and other romance languages than to English. A one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test shows that there was no significant difference in the mean nPVI among our five Jamaican Creole speakers, F (4, 112) = 1.82, p = 0.13. Therefore, our participant population provides an appropriate representation of mean nPVI for Jamaican Creole speakers. Mean nPVI for Jamaican Creole, some European languages, and dialects of English 70.0 46.0 Mean nPVI 47.6 59.9 49.3 42.1 We isolated the main melody from the riddim and separated each note. Comparison of speech and music: We plan to compare the relative durations of the music notes to the durations of vowels in speech using nPVI. 52.5 Mean nPVI Results + Discussion 59.7 Music: The music must be instrumental, because the rhythmic patterns in the melody of vocal music explicitly mimic the rhythm of speech, and we are interested in how speech patterns might implicitly affect the rhythm of instrumental music. Jamaican Creole between-speaker variation Above: A phrase of Jamaican Creole speech from producer Don Corleon. The waveform shows pitch contour, while the spectrogram shows formant values. We separated each phoneme and notated it in IPA in tier 1. Tier 2 categorizes each sound as a vowel or consonant. For our research using the nPVI formula, we only measured the relative duration of vowels. Jamaican Creole, some European languages, and dialects of English Jamaican Creole speakers No significant difference in mean nPVI of five Jamaican Creole speakers, F (4, 112) = 1.82, p = 0.13. References Daniele, J. R. & Patel, A. D. (2008). The interplay of linguistic and historical influences on musical rhythm in different cultures. The neuroscience institute: San Diego, CA. Fagyal, Zsusanna & Yaeger-Dror, Malcah. “Analyzing Rhythm: Best Practices in Sociophonetics.” New Ways of Analyzing Variation 39th Annual Conference. San Antonio. 14 Nov. 2010. Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2007). An Introduction to Language. Boston, MA: Thomson Wadsworth. Grabe, E. & Low, E. L. (2002). Durational variability in speech and the rhythm class hypothesis. Patel, A. D. (2008). Music, Language, and the Brain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Patel, A. D. & Daniele, J. R. (2002). An empirical comparison of rhythm in language and music. Cognition 87 (B35 B45). doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00187-7 Patel, A. D., Iversen, J. R., & Rosenberg, J. C. (2006). Comparing the rhythm and melody of speech and music: The case of British English and French. Acoustical Society of America, 119 (5), 3034-3047. doi: 10.1121/1.2179657