A s poetry response

advertisement

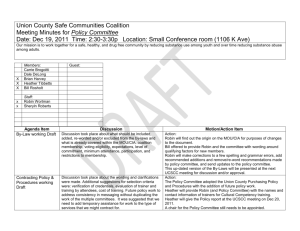

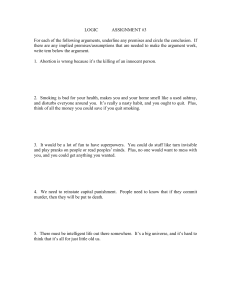

A* Analysis In 'Kid' and 'True North', how does Armitage deal with the theme of identity? In 'Kid' and 'True North' Armitage plays with the theme of identity. In 'Kid', he uses the extended metaphor of the Batman/Robin relationship to show the theme of coming of age, whereas in 'True North', he returns home - and deals with the issue of the dual yet separate identities of the Falkland Islands / Malvinas. 'Kid' uses iambic pentameter with a strong rhyme scheme and fast, punchy rhythm to create the feel of 'Robin's' upbeat, almost aggressive voice - as if he's asserting his identity against the 'Batman' character. This is symbolic of coming of age, and Armitage uses the pop-culture reference with further colloquial expressions - like punning news headlines screaming for attention: 'Holy robin-redbreast nest egg shocker!' The alliteration (robin redbreast/roll), news phrases and colloquial expressions tangle, violently, adding a fierce, coiled energy: 'Holy roll me over in the clover' is almost a tongue twister, with the assonance (holy/roll/over) and internal rhyme (over/clover) making it hard to make sense of. We feel the force of Robin’s energy straining to break free. The narrator uses cliched, unoriginal phrases to assert his own, unique identity: as if trying to force his way out of the cliche of the sidekick. In the end, he re-frames Batman, iconoclastically as 'stewing over chicken giblets' in the 'pressure cooker' - with the dual meaning of literal 'pressure', as if Batman has broken down with the force of this 'new boy wonder'. In ‘True North’, Armitage seems to be writing in his own person, in a calm, regularly structured piece that also uses iambic pentameter, but here, the mood is gentler - far more like normal conversation or telling a story than the rising hysteria of Robin’s voice in ‘Kid’. This poem is unrhymed, which adds to the more relaxed feel. Phrases like ‘bummed ride’ and ‘not much to crow about’ feel like someone at home in their own language - and their own identity - unlike the straining energy of Robin’s diction. The beginning of ‘True North’ describes the journey in matter-of-fact terms, linking to Armitage’s Northern heritage (Yorkshire, Marsden) of plain language, and unglamorous ‘cold’ ‘iced over’ and the loneliness of the setting in ‘unmanned’ stations. This suggests a cold welcome, as if he’s not totally at ease. He seems to find it smaller, suggesting he feels he has grown, describing the place as looking ‘stopped’ a mere ‘clutch of houses’ in a ‘toy snow storm’ - seeing it from a distance suggests he reconnects with his roots uncomfortably, seeing the smallness of it, separated. This theme of disconnection appears in the final stanza when he describes a ‘lecture’ - as if he’s an academic talking at people in a non-conversational way: when he’s with people in the pub - as if he no longer connects. In the final image, of ‘wolves’ and wounds (‘heals over’), he suggests a cold viciousness, of heartlessness - and the ‘Gulf’ is the yawning gap that now separates him from his original home, and the people in it. His politics are unlike theirs - he will get ‘asked outside’ (to fight) for saying ‘Malvinas’ (the Argentinian name for the Falkland Islands) ‘in the wrong place’. This last image of ‘the wrong place’ describes his home, as if it is now ‘wrong’ - showing his sense of dislocation that has come with his changing poltics and sense of self. Initially, Armitage goes home, in ‘True North’ thinking himself a hero ‘half expecting / flags or bunting’, and indeed the ‘drinks were on them’. However this later changes when he’s asked to fight. His fame is frail - and he hosts a game of burning through a tissue - to ‘dimp burning cigs’ - an unglamorous, childish pastime, of crossing through (the tissue) perhaps symbolic of the wanton destruction of crossing to the other side - (of Argentina vs the UK), mixing educated elegant words like ‘diaphragm’ deliberately with the colloquial baseness of ‘dimp’ and ‘cigs’ - to show that the two sides to his personality mix uneasily. His ‘guests’ ‘yawned their heads off’ when he talked, showing that from their point of view his new identity makes no sense - is uninteresting. In ‘Kid’, we see a similar discomfort between the popular view of Batman’s identity as superhero and the sordid truth. This suggests the fallibility of adults revealed as children grow up: that our heroes are more than we thought, and that the world is not so black and white. Armitage uses colloquial expressions ‘scotched’ the ‘rumour’, ‘let the cat out’ and ‘blown the cover’. The truth of ‘a married woman’ taken out ‘on expenses’ is sordid, and brings Batman to ‘next to nothing’ at the end of the poem, as if he’s fallen from grace. Robin re-presents Batman’s ‘order’ to ‘let me loose’ ‘freely’ to ‘wander’ as ‘or ditched me, rather’, stripping back fine words to reveal the unpleasant truth (from his point of view) showing multiple interpretations of the same event. In conclusion, Robin asserts himself violently in ‘Kid’, just as Armitage forgets home has become ‘the wrong place’ to say Malvinas. Armitage is aware he doesn’t quite belong, that a ‘Gulf’ has opened up, but gives a hopeful image at the end of it ‘healed’. In contrast, Robin asserts himself over Batman, as if he must overwrite him - the two versions of the truth can’t co-exist, the follower with the leader: Robin, now must be ‘the real boy wonder’, now he’s ‘taller, harder; stronger, older’. The list of comparatives suggest he only sees his identity in relation to Batman, and even in the end, doesn’t quite succeed in escaping the cliched phrase.