Writing Across the Curriculum

advertisement

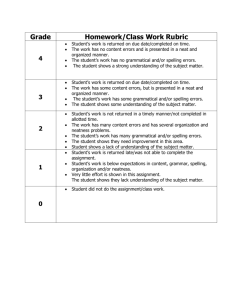

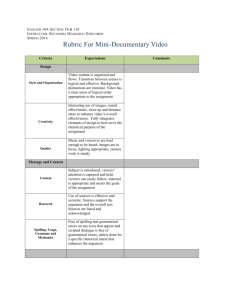

Writing Across the Curriculum Ellen M. Millsaps Prof. of English, Dir. Of WAC/Composition emillsaps@cn.edu Basic WAC Definition “Students use written language to develop and communicate knowledge in every discipline and across disciplines.” --Art Young What WAC Is Not: An add-on to the school’s curriculum: it is a way to teach the curriculum. Accomplished by assigning a term paper in every class Designed to add more work for you Busy work An effort by English faculty to have others do their work for them Why Write?? The National Commission on Writing First report to Congress, 2003: The Neglected “R”: The Need for a Writing Revolution Second report, 2004: Writing: A Ticket to Work. . .Or a Ticket Out, A Survey of Business Leaders Third report, 2005: Writing: A Powerful Message from State Government Some Overall Guiding Assumptions about Writing 1. Writing is a mode of learning. ** Assigning writing is a powerful mode of teaching. Writing Promotes Active Learning —National Training Laboratories, Bethel, Maine --Writing Assumptions, cont. 2. Learning a discipline also means learning the particular ways of writing in that discipline. Writing Assumptions, cont. 3. Informal writing exercises both complement formal writing assignments and are valuable in their own right. Some Informal Uses of Writing Five-minute free writes at the start of class to focus discussion on the topic. A “one-minute essay” to summarize the most important points of class or to ask a question to be addressed at the next class meeting. An answer to someone’s question about a problem, process, or concept. As an exit ticket from class. Some Uses of Writing Other than Research Papers Article Summary/Abstract Annotated Bibliography Review of Literature Case Studies Lab Reports Program/Exhibit Notes Lesson Plans News articles about disciplinary topic Reviews of lectures, performances “F.I.T” essays (Fact, Interpretation, Tie-in) Writing Assumptions, cont. 4. Learning to write is not like getting vaccinated against measles. Adapted from Doug Hesse, Univ. of Denver, 2007 “A geology professor in teaching students the knowledge that is geology as well as how to think, communicate, and solve problems like a geologist is initiating students into geology as a discipline and into science as a profession. Sometimes teachers fear that becoming involved in WAC means taking time away from geology—becoming an English teacher for 30 percent of the time—and they are understandably reluctant to do so.” “WAC says that a geology professor should not attempt to become an English professor at all. Geologists should teach geology, its knowledge and its ways of developing and communicating knowledge, and they should utilize written language as a tool to strengthen this teaching and learning of geology.” -Art Young, Teaching Writing Across the Curriculum Courses that Use Writing vs. Courses that Teach Writing Courses That Use Writing Courses That Teach Writing 1. Emphasis on teaching course content through having students actively engage information and ideas. Emphasis on students developing writing skills and strategies 2. “Getting better” as a writer is an indirect side benefit. “Getting better” as a writer is a direct and primary goal. 3. Class time features relatively little direct instruction in writing. Class time features direct instruction in writing. 4. Frequent shorter writings are prominent. Frequent shorter writings are prominent. 5. The focus of the course is on assigned readings, practices, or topics. The focus of the course is on the students’ texts created by writing. Courses that Use Writing vs. Courses that Teach Writing Courses That Use Writing 6. Response tends to focus on quality and accuracy of student thought and engagement. 7. Courses That Teach Writing Response tends to focus on these plus matters of presentation (rhetorical effectiveness, adherence to conventions, correct mechanics, etc.) Types of writing assigned may be Ditto. to facilitate learning or to emulate professional discourse. 8. Can be used in any class, large or small. Requires relatively fewer students because of time involved. 9. Presumes no special knowledge on the part of the instructor. 9. Asks instructors to possess knowledge about developing writing abilities and conventions of target genres. Doug Hesse, Univ. of Denver What Do You Do with Writing Once You Get It? Respond: To give informal reactions to text. Assess: To see how a student’s, or a class’s, body of work lines up with program or institutional objectives. Evaluate: To compare work with some sort of marker, benchmark, or standard. Grade: To condense all data into one symbol. Bradley Peters, Northern Illinois U., Council of Writing Program Admin. False Premises About Evaluation 1. 2. 3. 4. Instructors should write a lot in the margins and between the lines. Instructors ought to know and use many specific grammatical rules and terms if they want to comment effectively. The most effective responses to student writing are instructor-written comments on the final copy. Joyce MacAllister, “Responding to Student Writing” Every piece of writing needs to be graded. Tips for Assessing Writing 1. Tie the writing task to specific pedagogical goals. 2. Give written assignments that include your criteria for grading to make your expectations clear. 3. Weight your grading criteria to reflect your course priorities. 4. Require more than one draft of an assignment. Tips for Assessing Writing 5. Make good student papers available to illustrate features of strong work. 6. Set ground rules for yourself, and clearly convey to students what they can and cannot expect in terms of your response. 7. Develop a response rubric—a list of elements of the paper that you can check off. 8. Use evaluation options: choice depends on type, complexity, and purpose of assignment. Doug Hesse, “Response to Student Writing” Some Evaluation Options Credit/No credit Read and possibly share with class Accept/Revise/Reject Holistic Scoring Analytic Scoring Dichotomous Scales Rating Features Scales Generalized Checklists Weighted Analytic Scales Response/Grading Rubrics Holistic Scoring One score that considers all criteria at the same time. 1. Read quickly; score immediately. 2. Don’t reread. 3. Read the entire paper. 4. Read for what has been done well, not poorly. 5. Take everything into account: content, organization, grammar, style, etc. 6. Rank papers against others in the group. Holistic Scoring Scale 6 Extremely Proficient 5 Proficient 4 Moderately Proficient 3 Slightly Deficient 2 Deficient 1 Seriously Deficient The paper receiving a score of 6 generally has abundant, good details. The paper shows style and thought, and often there is a strong sense of the writer. This paper has few errors, as the writer seems in command of sentence structure and mechanics. The 5 paper is also detailed and developed with some sense of the writer showing through. The writer seems to understand sentence construction although problems with grammar and spelling can begin to arise. The 4 paper usually has a thesis developed in some significant way with support, although the paper may begin to lose focus, and it is not as detailed as a 5 and 6. Usually there is a sense of sentence construction even though it is not too sophisticated. Sometimes paragraph problems begin to appear. The 3 paper provides a clear picture of the subject or a sense of the writer, but it is developed with generalities. Grammatical, spelling, and sentence errors begin to dominate the papers. A 2 paper either has very limited and weak development and some grammatical/mechanical errors, or it attempts some development and is full of errors. A 1 paper extremely short with virtually no development at all. (In a few instances, a 1 may be given for an off-topic paper in which the student did not understand the topic at all.) Holistic Scoring Uses For For For For papers in large or small classes “micro themes” “one-minute essays” journal entries Dichotomous Scales Feature “Yes” or “No” responses. Useful in program evaluation of a common set of writing characteristics. Example: 1. 2. 3. Is there a thesis statement? Yes __ No __ Is there thoughtful analysis? Yes__ No __ Are sources used correctly? Yes__ No __ MLA Format: Brief Assessment General Format: 1. Yes No Essay's first page has correct format for margins, headers, double-spacing, student's name, the teacher's name, the course, and the date in the upper left-hand corner as required by MLA, 2. Yes No Long quotations (four lines or more) are indented in block format (i.e., the left margin is adjusted by a full two tabs, but no special indentation appears on the right-hand side of the page) and the period appears in the correct location with the parenthetical citation. 3. Yes No Student judiciously uses ellipses correctly to indicate missing material and uses spacing before and after each period, or the student uses brackets [like so] around additional inserted material for clarity or grammatical consistency. 4. Yes No Student introduces and integrates quotations smoothly into the content of the essay--the student explains quotations and gives context for the reader rather than inserting inert quotations. 5. Yes No Students cites paraphrasing in such a way that it is clear where their own ideas begin and end and where source material begins and ends. Works Cited: 6. Yes No Each line of the Works Cited page is double-spaced. 7. Yes No The Works Cited page uses hanging indentation in which the first line of each entry is flush with the left-margin and subsequent lines within each entry are indented one tab. 8. Yes No Student includes the Works Cited information for each entry in the appropriate order leaving out unnecessary abbreviations like "Vol." and "No." and "p." 9. Yes No Student alphabetizes entries by author's last name or by title if no author or editor is given. 10. Yes No Student remembers to use abbreviated format for lengthy URLs for databases like JSTOR, InfoTrac. Analytic Scoring Guides Quality of Ideas (______ points) Range and depth of argument; logic of argument;; quality of research or original thought; appropriate sense of complexity of the topic; appropriate awareness of opposing views. Organization and Development (______ points) Effective title; clarity of thesis statement; logical and clear arrangement of ideas; effective use of transitions; unity and coherence or paragraphs, good development of ideas through supporting details and evidence. Clarity and Style (______ points) Ease of readability; appropriate voice, tone and style for assignment; clarity of sentence structure; gracefulness of sentence structure; appropriate variety and maturity of sentence structure. Sentence Structure and Mechanics (______ points) Grammatically correct sentences; absence of comma splices, run-one, fragments; absence of usage and grammatical errors; accurate spelling; careful proofreading; attractive and appropriate manuscript form. (Bean, Engaging Ideas 258-259) Analytic Scoring Guides Quality of Ideas (50 points) Range and depth of argument; logic of argument;; quality of research or original thought; appropriate sense of complexity of the topic; appropriate awareness of opposing views. Organization and Development (30 points) Effective title; clarity of thesis statement; logical and clear arrangement of ideas; effective use of transitions; unity and coherence or paragraphs, good development of ideas through supporting details and evidence. Clarity and Style (10 points) Ease of readability; appropriate voice, tone and style for assignment; clarity of sentence structure; gracefulness of sentence structure; appropriate variety and maturity of sentence structure. Sentence Structure and Mechanics (10 points) Grammatically correct sentences; absence of comma splices, run-one, fragments; absence of usage and grammatical errors; accurate spelling; careful proofreading; attractive and appropriate manuscript form. (Bean, Engaging Ideas 258-259) Diederich Scale for Raters of Writing Scale: 1 = Poor 2 = Weak 3 = Average 4 = Good 5 = Excellent Categories of Writing Qualities: Quality and development of ideas (textual evidence & analysis) Organization, relevance, movement 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 _______ x5 = ______ Style, flavor, individuality Wording and phrasing 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 subtotal _______ x3 = ______ Grammar, sentence structure Punctuation Spelling Manuscript form, legibility, MLA 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 subtotal _______ x1 = ______ subtotal Total Grade = _________ Diederich Scale for Raters of Writing Scale: 1 = Poor 2 = Weak 3 = Average 4 = Good 5 = Excellent Categories of Writing Qualities: Quality and development of ideas (textual evidence & analysis) Organization, relevance, movement 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 x5 Style, flavor, individuality Wording and phrasing 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 = 30 subtotal ____6__ x3 = _18____ Grammar, sentence structure Punctuation Spelling Manuscript form, legibility, MLA 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 subtotal ___12____ x1 = _12_____ subtotal Total Grade = __60_______ Diederich Conversion Chart Converted Scale: Grade Book: Poor = 1 = F Below 30 Weak = 2 = D 30-49 Average = 3 = C 50-69 Good = 4 = B 70-89 Excellent = 5 = A 90-100 A = 98 A- = 94 B+ = 93 B = 90 B- = 85 C+ = 83 C = 80 C- = 75 D+ = 74 D = 72 D- = 70 F = 64 Diederich Conversion Chart Converted Scale: Grade Book: Poor = 1 = F Below 30 Weak = 2 = D 30-49 Average = 3 = C 50-69 Good = 4 = B 70-89 Excellent = 5 = A 90-100 A = 98 A- = 94 B+ = 93 B = 90 B- = 85 C+ = 83 C = 80 C- = 75 D+ = 74 D = 72 D- = 70 F = 64 Rubrics: Why Use? Save time; keeps from repeatedly saying the same things Make grading more efficient Make grading more consistent Help students know what to expect/how to respond to assignment Can more easily assess group learning Recognized as a valid measure by some accrediting bodies Creating Grading Rubrics for Writing/Research Assignments Step One: Identifying the criteria. What are the assignment’s learning outcomes or objectives? Step Two: Weighting criteria. What should count the most? Ten ranked items is usually upper limit. Use specific and descriptive criteria. Step Three: Describing levels of success. Numerical scales Descriptors Step Four: Creating and distributing the grid. (Pamela Flash, Assoc. Dir., CISW, Univ. of Minnesota) Sample Writing Rubric Weak Insights and ideas that are germane to assignment Address of target audience Choices and use of evidence Logic of organization and use of prescribed formats Integration of source materials Grammar and mechanics Comments Final Grade Satisfactory Strong Sample Writing Rubric 1 = not present, 2 = needs extensive revision, 3 = satisfactory, 4 = strong, 5 = outstanding 1 Insights and ideas Address of target audience Organization and use of prescribed formats Integration of source materials Grammar and mechanics Comments/Final Grade 2 3 4 5 English Department Rubric for Essays Assessment Thesis/enthymeme is clearly stated, makes a point that is thought provoking, and reflects critical thinking. Content reflects college-level thinking. Paragraphs are well-organized; topic sentences and transitions are used effectively to introduce and link body paragraphs Paragraphs are well-developed; examples, quotations, images, or other specific details are used effectively as support. Sentence structure is economical and varied. Language is precise, appropriate. Essay avoids errors in grammar, punctuation, spelling, and proofreading. The writer demonstrates an individual voice. 1 2 3 4 5 WAC Principles Students learn more when they are engaged with the subject. Writing is a unique tool for engaging students in learning. Not every piece of writing needs to be graded or lead to a final product for learning to occur. You are the best person to teach students how to use writing in your disciplinary field. Students will regard writing as important for all disciplines, and not just English, when they see other professors valuing it as a means for learning and its necessity for job performance. Works Cited Bean, John. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrting Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996. Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form. 3rd ed., U of California P, 1973. 110-111. Emig, Janet. “Writing as a Mode of Learning.” College Composition and Communication 28 (May 1977): 122-28. Hesse, Doug. “Response to Student Writing: Thirteen Ways of Looking at It.” - - -. “Writing beyond Classes: Useful Strategies for Busy Professors.” Univ. of Denver. April 2007. dhesse@du.edu “Learning Pyramid.” National Training Laboratories. Bethel, Maine. The Abilene Christian University Adams Center for Teaching Excellence. 2000. 30 Oct. 2007. http://www.acu.edu/cte/activelearing/whyuseal2.htm Works Cited MacAllister, Joyce. “Responding to Student Writing.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning: Teaching Writing in All Disciplines, no. 12. San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1982. McLeod-Porter, Delma. “Guidelines for Assessing Writing in Writing Enriched Courses: How to Mark Student Papers and Retain Your Sanity.” PowerPoint Presentation, McNeese State U., 2007. The National Commission on Writing. The Neglected “R”: The Need for a Writing Revolution. College Board, 2003. - - -. Writing: A Ticket to Work…or a Ticket Out, A Survey of Business Leaders. College Board, 2004. - - -. Writing: A Powerful Message from State Government. College Board, 2005. Works Cited Peters, Bradley. Council of Writing Program Administrators Listserv. 24 Oct. 2007. http://www.nabble.com/Assessment-t4685452.html “Rubrics.” St. John’s Univ. 26 Oct. 2007. http://www.stjohns.edu/academics/provost/assessment/co reassessment/rubrics.print Young, Art. Teaching Writing Across the Curriculum. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999.