Choi_InstantFilmFinal

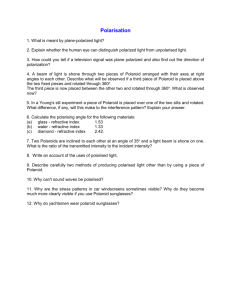

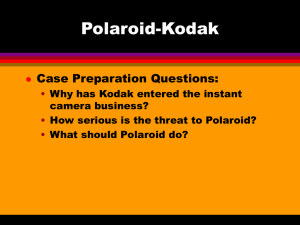

advertisement

Catherine Choi INF 392E: Materials in Libraries, Archives, and Museums Lecturer Karen Pavelka Preservation Issues of Instant Film Photography As instant-film giant Polaroid reached the end of its run of instant film production in 2008, having undergone a series of financial struggles at the turn of the 21st century, it appeared that the future of the medium was gravely uncertain. In general, analog film cameras have become antiquated with the surge in popularity of their more modern, digital counterparts in recent years, with Polaroid being no exception. Instant photography has always had somewhat of a dubious status in both the field of photography and the realm of modern art, as some have argued that it requires little artistry or technical skill on part of the artist. Historically, its immense popularity and mass-market appeal had led to its reputation as more of a novelty item or toy rather than a means for a serious art form. Many artists have contested this notion though, as later mentioned, including respected contemporary artists Lucas Samaras, Robert Mapplethorpe and Rosamond Purcell. Moreover, there’s no denying the impact that Polaroid had on both the art world and general public. We are currently left to wonder moving forward the impact that this will have on the conservation of instant film photography, particularly in consideration of the bearing this may have to its cultural value as vintage medium. In light of the recent demise of the company, the public has certainly taken notice of the situation, as Sotheby’s auction of the Polaroid Corporation holdings in 2010 garnered more than $12 million in sales (Russeth, 2010). There has also 1 been a revived interest in Polaroid prints that numerous renowned artists, many of whom are arguably better known for their works in other media (i.e. Ansel Adams, Andy Warhol and Chuck Close), generated throughout the years. There has been a critical lack of research regarding the preservation of instant film photography, as the prints had mostly been cast off as ephemera in the past. Art institutions whose collections contain Polaroids have certainly done their best to maintain their works, however, more current studies need to be performed to address the ongoing preservation issues associated with instant prints, and perhaps more importantly, tackle the shifting perceptions the art world and general public has upon instant film photography. Each Polaroid print was once regarded as highly disposable due its “instant” nature and capability of quick consumption. However, in retrospect, the discontinuation of Polaroid film and lack of negatives for many of their film types have made these objects highly unique and unable to be replicated. History of Polaroid This paper will predominantly focus on the maintenance of Polaroid films, as they were the only company to produce instant film for several decades. Polaroid was the pioneer of the technology with the introduction of Polaroid Land Camera Model 95, the first instant camera, in 1948 (Baker Library, 2012). As the sole producer of instant films during the next three subsequent decades, the name of the corporation became synonymous with the instant photography process itself. They experienced commercial success for many years, having created a revolutionary type of film that could instantly develop prints without the 2 need of a darkroom (Buse, 2008, p.222). Their one-step, simplified shooting technique allowed for mass consumption of the product, “automating all aspects of picture-taking, gradually removing all responsibility from the camera operator for all functions except selection and framing of subject matter…” (p.221). Polaroid’s most successful camera model was the SX-70, introduced in 1972. It was the first foldable, automatic single-lens reflex (SLR) camera of its kind and the first device to implement use of their newly developed integral color film. As Harry McCraken, editor at large for Time and founder of their technology blog Technologizer, explains the motivation for including the SX-70 in his list of the “fifty greatest gadgets of the past fifty years”—he proclaims that the criteria resided in “Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law: making technology indistinguishable from magic. By that measure, I can’t think of a greater gadget than the SX-70 Land Camera…” (McCraken, 2011). It was the first device that fully realized the dream of Polaroid’s founder, Edwin Land, by creating an entirely “one-step process.” Land’s original vision was sweetly inspired by a simple question posed by his daughter on a family vacation, asking “how soon she could see the picture that father had just taken” (Time, 1980). His ability to execute this creation was no fluke, as he personally owned more than 500 patents by time he stepped down as Chairman of Polaroid in 1980 (Time). The integral instant film type that was introduced with the SX-70, which will be discussed in further detail later in this paper, produces prints that include both the positive and negative in a sealed “integral” film unit. Integral film technology is unquestionably very advanced; each print includes a multilayered 3 emulsion that allows the diffusion of silver or dyes to the image layer depending on the amount of light exposed to an area (Warren, 2006, p. 1303). The iconic appearance of integral film facilitates the identification of Polaroid prints, with its thick white frame and wider border along the bottom of the image. The unique size of the frame, actually a product of the film’s function, has become a curious source of nostalgia for those living in the present, digital age. Software applications like Polaroid allow an individual to easily add a “Polaroid frame” around any of their digital images. Eastman Kodak attempted to enter the instant film market in 1976 but their products never faired well against those of Polaroid’s, and they were eventually ruled in violation of several Polaroid patents that led to a mandated cease in production of impacted materials (McCraken, 2011). Fujifilm entered the instant film market in the 1990s, and is still presently in the business of instant film manufacturing (Lavédrine, 2007, p. 218), the only other company aside from the recently formed Impossible Project. Black-and-white and Color Instant Film The different types of Polaroid film can generally be divided into those that produce either black-and-white or color prints—however both have had somewhat different variations on processes, particularly since technology has changed throughout the years since its inception in the 1940s. All instant films, however, use methods of dye diffusion transfer to produce the image, a process that involves the movement of dyes from the negative to the resulting positive 4 print. This is made possible by the fact that all materials needed for the development of the final print is contained within a Polaroid film unit—the negative, positing image-receiving sheet and pod filled with developing chemicals (Duffy, 1983, p.11). The first Polaroid process invented by Edwin Land allowed for instant black-and-white “peel-apart” prints that “combined the film negative (triacetate or polyester), the silver gelatin positive print, and the developing chemicals in one unit” (Ritzenthaler & Vogt-O’Connor, 2006, p.47). The development method for this film, known as (alkaline induced) dye diffusion transfer, begins with exposed film that is chemically treated with a strong alkaline (typically sodium or potassium hydroxide) in the form of a gel that is released from a pod broken open as the film unit passes through metal rollers upon exiting the camera (Nishimura, 1993). Silver halides diffuse into the “receiving layer” adjoining the exposed negative to form the positive print—then the negative layer with the developing chemicals are peeled from the positive layer (Lavédrine, 2007, p.218). Negatives were discarded for some film types, but 665 and 55P/N films allowed for reuse of the negatives for producing other subsequent prints. (Ritzenthaler & Vogt-O’Connor, 2006, p.47) Instant color film, which was introduced in the 1960s, possesses the addition of opacifying dyes in yellow, magenta or cyan, with each color compound held within a separate photosensitive layer in the color film unit. The dye components perform as developers in the presence of the alkaline gel—the reagent that is emitted from the pod that is broken open when being spit out of 5 the camera (as mentioned earlier)—and is spread over the film. As the reagent moves to the receiving layer, the dyes become static in the film’s exposed areas where the silver halide becomes oxidized and “in the nonexposed areas dyedeveloper molecules remain unreacted and are free to diffuse into the imagereceiving layer, where a full-color positive image is formed” (Lavédrine, 2007, p. 219). The alkaline also diffuses through a timing barrier (which sits behind the image-receiving sheet along with an acid), producing water and salt, which in turn, creates an alkaline solution. These developing chemicals remain on the surface for integral films and peeled off in other types. Types of Film Earlier Polaroid films were “peel-apart,” entailing the separation of the positive and negative components of the print after processing occurred. All of the black-and-white roll films that Polaroid produced from 1950 to 1970 necessitated the use of a Polaroid-brand print coating on the resulting positive print after the processing took place, to guard the surface of the image from any inappropriate handling or chemical damage. By 1970, films were introduced that did not require the use of a coater, but some preceding coater film types are still produced today (Mesquit & Lemmen, 2005, p.182). Even though Polaroid claimed that a thick application of the coating would provide a highly stable image, earlier coaters were only found to protect the prints from surface damage (Mesquit & Lemmen, p.183). The black-and-white silver images were still vulnerable to chemical damage, and furthermore, failed to wash away any 6 residual water-soluble deposits that remained on the images from processing solutions. A new solution introduced in 1951 proved to be a better solution, however, inadequate coating by consumers caused prints to fade or discolor. Tests performed at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) of coated prints reveal that Polaroid continued to introduce new variations of the coating solutions during the subsequent years. After 1954, scientists found a consistent presence of the polymer poly(vinyl pyridine) replacing the former poly(vinyal acetate) (PVAc) in the coatings—however, concentrations differed for protection of different film format prints to “control the viscosity, flow rate, and/or drying time” (p.185). Coated prints can generally be identified easily by their high gloss and/or imperfections due to inconsistent coating. The initial color films that Polaroid introduced, including Polacolor 2 (a later version of the original Polacolor) and Polacolor ER also created peel-apart prints. In contrast to their black-and-white counterparts, the complete drying time for these images took much longer averaging around a few minutes, depending on the relative humidity of the environment (Duffy, 1983, p.11). In 1972, Polaroid launched the SX-70 Land Camera model which also introduced the emergence of integral color film, which is the predominant type of existing color prints that is associated with instant photography (McCracken, 2011). Integral color film uses the same processing method as peel-apart prints, namely, dye diffusion transfer. However, the negative and positive form one 7 distinct unit that stays together after processing and the resultant image is sealed tight behind a polyester sheet window (Duffy, 1983, p.12). The pod of developing chemicals sits below the image behind the receiving layer, giving the instant print its characteristically taller border along the bottom edge—a 4 1/4 x 3 1/2 in. print with a square 3 1/8 x 3 1/8 in. image (Lavédrine, 2007, p.219). Preservation and Storage The Polaroid Corporation published a preservation guide in 1983 that outlined the films manufactured thus far, including recommended storage and display methods. Many of their suggestions are applicable to all photographs. The guide states that Polaroid prints should not be stored with any other materials, especially other photographic prints and any other papers. Other images that have been poorly developed may possess residual chemicals from improper washing and fixing, which could be particularly damaging to neighboring prints if stored together. Any storage containers for the Polaroids should have a neutral to slightly alkaline pH (between 7.0 and 8.5). Ideally, prints should be kept individually in acid-free paper sleeves or envelopes “with a high alpha cellulose content, or of cellulose acetate, polyethylene, or polyester” (Duffy, 1983, p. 28). Temperatures in storage units should remain “within a temperature range of about 60-70°F (16-21°C), at a relative humidity of 30-50% (Duffy, 1983, p.23). If the environmental conditions are too dry, instant prints have been found to crack on the image-receiving layer, even though the polyester cover and backing 8 for the image remains unaffected (Wilhelm, 1993, p.124). Light does not appear to affect the cracking, except for situations where it causes a dramatic raise in temperature, as would be the case if placed in direct sunlight. The Polaroid Corporation claims that such issues should not occur with films released after 1980, due to advances made in the technology and has interestingly failed to reveal any information regarding the testing performed to evaluate the cracking problems (Wilhelm, p.125). Polaroid prints, as with most photographs, are vulnerable to air pollutants and damage that may incur through direct contact with any chemicals or offgassing materials, including “oxides of sulfur and nitrogen, chlorine, peroxide, hydrogen sulfide, ozone, vapors of ammonia, auto exhaust fumes, and the fumes given off by paint, varnish, solvents, bleach and cleaning agents” (Duffy, 1983, p.23). Duffy notes that some of these particular elements, such as chlorine, can be found in regular tap water (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2012). It appears that the black-and-white Polaroid prints are fairly stable under adequate storage conditions and typically have few preservation issues, other than slight yellowing that may occur. However, its silver-based process makes the image susceptible to oxidation, thus it should be stored away from any oxidizing agents (Lavédrine, 2007, p.219). Black-and-white prints are not as vulnerable to light as color images, but may fade if improperly stored or inadequately coated (Duffy, 1983, p.22). 9 Color Polaroid prints are much less stable than black-and-white photographs, and suffer the same risks that all color images do in terms of vulnerability to light and susceptibility to fading. According to Henry Wilhelm (1993), the company had “made numerous misleading claims about the dye stability of its materials” (p.125-126), formerly claiming that “its brilliant colors are among the most permanent and fade resistant ever developed in photography” (p.125). Color integral film prints are particularly sensitive to damage, as the negative and positive are sealed together in one unit. There is no way of washing away any chemicals after the processing takes place, and prints may lead to eventual fading, cracking and/or discoloration (Art Gallery of Ontario). Integral prints are actually very stable in dark storage, but the residual processing chemicals and non-image color dyes can migrate under normal room temperatures even if kept away from the light. Migration of these components can lead to yellow staining on the image layer. Wilhelm notes that accelerated testing of the materials’ stability, as explained below, wasn’t even necessary for some film types as they exhibited stains in just a few years in real-time (Wilhelm, p.124). Light appears to be the biggest adversary of color integral photographs, as demonstrated by experiments performed by Henry Wilhelm regarding the “Comparative Dark Fading and Yellowish Staining of Polaroid, Fuji, and Kodak Instant Color Prints…” indicating both the “Number of Days Required for a 20% Loss of the Least Stable Image Dye in Accelerated Dark Fading Tests at 144°C (62°C) and 45% RH.” The accelerated testing demonstrated that some integral 10 film types introduced in the late 1980s to early 1990s, including Polaroid 600 Plus Prints, Polaroid Spectra Prints and Polaroid Vision 95 Prints only took half the time to reach the same level of 20% loss of the least stable image dye than other films and exhibit very poor stability in light in regards to fading. Color peel-apart film prints, including Polaroid ER, Polaroid Polacolor and Polacolor 2, store better than integral prints since the negative layer possessing all the developing chemicals can be discarded after use (Wilhelm, p.124). However, if the prints have not been processed an adequate amount of time or under temperatures not high enough, they will be more susceptible to chemical damage (Duffy, p.23). Other Films As mentioned earlier, Fujifilm still produces instant film today, with their line of Instax films. Unfortunately, their products are so new and not nearly as popular as Polaroid film when they were still in production, that there has been a dearth in studies regarding the stability of the Fujifilm prints. An interesting twist in the supposed demise of instant photography is the recent development of the Impossible Project—a company formed by a few former members of the Polaroid Corporation that were dedicated to preserving analog instant film, in addition to saving the last remaining Polaroid production factory in Enschede, The Netherlands. Impossible integral films are specifically designed to be useable in Polaroid cameras, preventing millions of cameras from becoming obsolete. Even though Impossible was using the same manufacturing 11 plant as Polaroid, they had to investigate an entirely new formula for the instant film, as the chemicals used for Polaroid’s film were discontinued. One of the film’s components, “a special sort of titanium dioxide which was made only by a DuPont plant in DeLisle, Miss., was wiped out by Hurricane Katrina” (Gilbert, 2010). Polaroid actually manufactured many other chemicals that were essential to the production of instant films in the United States as well, but suspended operations after the company attempted to simply store up supplies for future needs. As Impossible’s Head of Research and Production André Bosman and former engineer at Polaroid remarked, ‘Color film… has to ripen, mature, develop the flavor for two years, like a wine. There was no wine’ (Dougherty, 2009). After much experimentation, Impossible’s latest line of color films behave very similarly to Polaroid 600 film and has been found to be rather pleasing in quality to instant film enthusiasts (Reed, 2012). However, with a completely new chemical composition in film, recommended preservation methods and print stability are uncertain at this point in time. As Impossible seems to still be in the process of tinkering with their film formulas, further testing for image permanence and preservation should be executed in the near future—possibly in the next few years when their line of films are more stable in composition. Concluding Remarks As Peter Buse comments on the downfall of Polaroid: “Like any once popular commodity on the brink of extinction, Polaroid cameras are now the 12 subject of widespread nostalgic sentiment…” (Buse, 2008, p.20). The enormous surge in modern photographic technologies has perhaps made us even more nostalgic for obsolete media, as can be demonstrated by the popularity of vintage filters on digital photography applications and software. This seemingly renewed interest in instant photography as an art medium at the cost of Polaroid’s fall may provoke an increase in research regarding the preservation of these unique materials. What seems evident, is that while instant film photography has been garnering more attention in the public eye in the last few years, the unyielding attraction from Polaroid enthusiasts, artists and collectors alike has allowed the medium to survive the immense blow of the product’s discontinuation. In a recent article for Print magazine, editor Jude Stewart probes the reasons why people may be so attracted to Polaroid prints. She offers up a mix of qualities that instant photography possesses that gives its allure, but the reasons all seem to reside in the print’s undeniable charm. What once appeared “instant” for Polaroid processes now actually takes longer for us to view than what we’ve become accustomed to with our ability to immediately preview our digital photographs. This allows for an element of surprise that ceases to exist with modern technologies. The simplicity of the method, Stewart states, is what has permitted artists such as Lucas Samaras, who performs wild manipulations to Polaroid prints, Robert Mapplethorpe and David Hockney, to each take their own spin on the art form (Stewart, 2012). 13 As long as this continued interest remains, conservators, manufacturers and cultural heritage institutions need to continue exploration into the future of instant photography in order to preserve the impressive legacy that Polaroid has left on our culture. They also need to acknowledge the continued success of recently introduced Impossible film, including its popularity among contemporary artists. This will necessitate further investigation into the stability of these materials with their entirely new chemical compositions and require management plans for these novel print media. 14 References Art Gallery of Ontario. (2012, March 29). How to conserve a Polaroid [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QqgVBnlWFAA Baker Library. (2012). Polaroid instant camera. Retrieved from http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/nd/contemporary-leaders/polaroid-instantcamera/ Buse, P. (2008). Surely fades away: Polaroid photography and the contradictions of cultural value. Photographies, 1(2), 221-238. Dougherty, C. (2009, May 25). Polaroid lovers try to revive its instant film. The New York Times. Duffy, P. (Ed.). (1983). Storing, handling, and preserving Polaroid. Cambridge, MA: Polaroid. Gilbert, S. (2010, March 23). Crazy, magic, impossible: Polaroid film is back. Retrieved from Daily Finance website: http://www.dailyfinance.com/2010/03/23/crazy-magic-impossible-polaroidfilm-is-back/ Lavédrine, B. (2007). Photographs of the past: process and preservation. Los Angeles, CA: Getty. McCracken, H. (2011, June 8). Polaroid’s SX-70: the art and science of the nearly impossible [Blog post]. Retrieved from Technologizer website: http://technologizer.com/2011/06/08/polaroid/ Mesquit, T., & Lemmen, B. (2005). [Coatings on Polaroid Prints]. In Coatings on photographs. Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Conservation. 15 Nishimura, D. (1993, October 1). Polaroid prints [Blog post]. Reed, R. (2012, October 4). Why Polaroid inspired both Steve Jobs and Andy Warhol. Smithsonian. Ritzenthaler, M. L., & Vogt-O'Connor, D. (2006). Photographs: archival care and management. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists. Russeth, A. (2010, June 22). Controversial Polaroid auction triumphs at Sotheby's. Retrieved from http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/35016/controversial-polaroid-auctiontriumphs-at-sothebys Stewart, J. (2012). The unsinkable Polaroid film. Print. Time. (1980, March 17). Polaroid's Land steps down. Time, 115(11). United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2012, June 5). Drinking water contaminants. Retrieved from http://water.epa.gov/drink/contaminants/index.cfm Warren, L. (2006). Encyclopedia of twentieth-century photography. New York, NY: Routledge. Wilhelm, H. (1993). The permanence and care of color photographs. Grinnell, IA: Preservation Publishing Co. 16