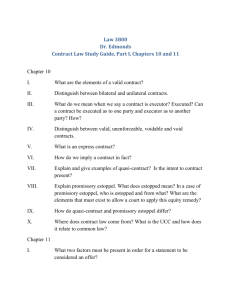

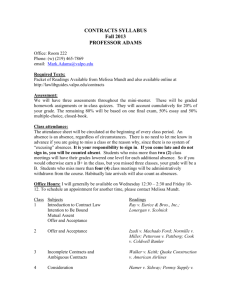

Contracts I – Wilmarth – Fall 2009

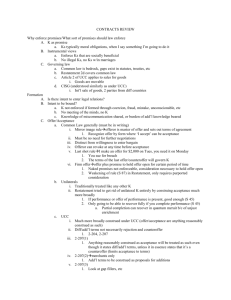

advertisement

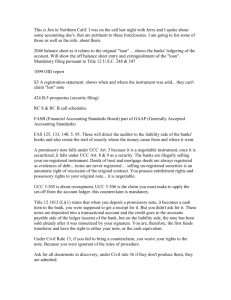

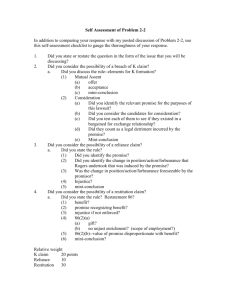

DON’T USE §87(1)(a) – CL firm offer rule for bilateral option contract §90(2) – charitable pledge can be binding w/o forebearance (because they are not widely accepted by the courts) USE UCC Revised §§ 2-206 and 2-207 (all else use original UCC articles CONTRACTS I – WILMARTH – FALL 2009 I. Classic contracts: Mutual Assent & Consideration A. Mutual assent - an agreement to a common set of terms Ray v. Eurice – absent fraud, duress, or mutual mistake, signature indicates mutual assent Skrbina – claims of not understanding portions of a signed release do not exempt the signer of the release from any provisions contained in the release Lonergan v. Scolnick – an offer requires acceptance to be a binding offer -mailbox rule (§63): if acceptance was mailed before revocation, offer is binding (unless offer specifically conditions “acceptance on receipt”, valid as soon as it leaves promisee’s possession) - “specific performance” – forcing fulfillment of the terms of the contract - the third party who lost property he purchased through valid contract as a result of the court awarding property to the first acceptor can often sue for damages - “restitution” – gives injured party amount measured by the benefit the injured party conferred on the contract breaker -The important legal object is the physical manifestation – the written signed document - §36: The power to accept is cut off in the case of: 1) rejection or counteroffer by the offeree 2) lapse of time 3) revocation by the offeror 4) death or incapacity of the offeror or offeree - §41: an offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated at the time specified in the offer, or, if no time is specified, at the end of a “reasonable time” -§33: defines certainty of terms, prerequisite to forming a contract. Normile v. Miller – real estate option case -if you give someone an option and don’t specify otherwise, that offer is exclusive -a “conditional” or “qualified” acceptance is not an acceptance, but really a counteroffer -options can be revoked prior to acceptance (no mailbox rule for options) -priority goes to the first acceptance in time B. Bilateral vs. Unilateral contracts – §32 (and comments) Bilateral contract – promise in exchange for a promise of performance (consid. is promise) Unilateral contract – promise in exchange for only a performance (consid. is performance) -§50: Bilateral contract acceptance occurs when a return promise is made Unilateral contract acceptance occurs when part of the performance is executed Petterson v. Pattberg – court held that the agreement, a unilateral contract, can be revoked at any time before the act (the payment of the money) had been performed §45: (for unilateral option contracts) -“where an offer invites an offeree to accept by rendering a performance and does not invite a promissory acceptance, an option contract is created when the offeree tenders or begins the invited performance or tenders a beginning of it.” (part performance) Cook v. Coldwell Banker – realtor sued after she left firm; she left because she wasn’t paid the bonus she was promised and firm claimed she violated agreement by leaving -bonus offer was not revocable because Cook had completed and continued part performance -An offer to make a unilateral contract is accepted when the requested performance is rendered C. Consideration -every contract requires mutual assent and exchange of consideration -consideration consists of a benefit to the promisor and/or a detriment to the promise -§69: “when an offeree fails to reply to an offer, his silence is not acceptance except…” (acceptance by silence: takes benefit w/ reasonable opportunity to reject, offeror gives reason to understand that assent may be manifested by silence, or previous dealings lead to assumption) -§71: consideration must be bargained for (promise induces perform. / perform. induces promise) -§73: performing things that one is legally obligated to do or abstaining from things which one is legally prohibited from doing is not consideration -§77: “illusory” promise (performance optional with promisor) will not serve as consideration -§79: if consideration is met, no additional req. of a benefit or detriment (or “mutuality”) Hamer v. Sidway – the “classic case”; any forbearance of legal rights was valid consideration (smoking) Pennsy Supply, Inc. v. American Ash Recycling Corp. – American Ash got a benefit from not having to dispose of the toxic aggregate ash; therefore, the “quid pro quo” is free aggregate for Pennsy and no disposal costs for American Ash (enforceable contract b/c of consideration) Dougherty v. Salt – the court found that the promissory note from aunt to nephew was a gift that did not require any promise or forbearance (no consideration, no enforceable contract) -no requirement of value equity, but consideration cannot be merely nominal Batsakis v. Demotsis – enforcement of loan agreement made in drachmae; the court finds that the contract is enforceable despite lack of equity because there was some consideration -mere inadequacy of consideration will not void a contract (but gross inadequacy is relevant) Cobaugh v. Klick-Lewis, Inc. – man hits hole in one and sign offering prize is still up - “the promoter of a contest, by making public the conditions and rules of [it], makes an offer, and if before the offer is withdrawn [someone] acts upon it, [he] is bound to perform his promise.” -knowledge of the offer and intent to accept is necessary Plowman v. Indian Refining Co. – company stopped paying pension GM promised to pay -former VP and GM did not have authority to make enforceable pension promises; there was no consideration b/c past performance (service to company) and conditions (coming to pick up check) cannot be consideration Types of authority: 1) Actual expressed authority 2) Actual implied authority 3) Ratification of authority -“moral duty” can’t be a legal guide to the validity of a promise b/c it is not a universal standard (moral viewpoint of the promisor may be different than that of the promisee) II. Obligation without contract: Promissory Estoppel & Restitution A. Promissory Estoppel -promissory estoppel is not a type of contract; it is an equitable alternative theory of obligation to support agreements that lack consideration (1) a promise, (2) that induces a detrimental reliance on that promise, and (3) injustice can only be avoided by enforcement of the promise Kirksey v. Kirksey – sister moved her family to brother’s land after husband died -court on appeal says that there was no consideration on the sister’s part, finding that the promise by the defendant was “a mere gratuity”; dissenting judge finds consideration in the process of moving and the distance she moved (60 miles) Ricketts v. Scothorn – granddaughter quits her job when grandfather promises money -unlike Hamer b/c no bargain; unlike Dougherty because she relied on the promise -court responds with theory of equitable estoppel, since promise induced plaintiff to change position for the worse -Judge in Ricketts adds a quality of inequity to the doctrine of equitable estoppel: it simply wouldn’t be fair to not give plaintiff Katie the money -the question under promissory estoppel is whether or not there is a substantial or definite reliance on the promise (to individual’s detriment) in the inducement of the subsequent action Greiner v. Greiner – family dispute between mother and disinherited son -court, after finding detrimental reliance, decides whether to award Frank the deed to the land or simply to compensate him monetarily for what he suffered -§90 defines and outlines doctrine and requirements of promissory estoppel -“The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires” Congregation Kadimah Toras-Moshe v. DeLeo – Court finds that there was no reliance because the congregation had not begun the construction of the library and thus had not relied to its detriment on the promise (they could just scratch expenditure from budget) King v. Trustees of Boston University – suit to recover MLK’s papers from BU -the jury found no contract; the issue is whether the question was properly submitted (was the agreement “supported by consideration or reliance”?) Allegheny Coll. v. Chautauqua County Bank of Jamestown – donation promise to college -Cardozo does not try to fit a unilateral contract; he finds a bilateral contract with consideration (Yates promises to give $5k with conditions, college accepts payment which constitutes acceptance) -“A duty to act in ways beneficial to the promisor and beyond the application of the fund to the mere uses of the trust would be cast upon promisee by acceptance of the money.” Katzv. Danny Dare, Inc. – pension given to older man injured, suit when payment stops -court finds all three elements of promissory estoppel: promise of pension, reliance on pension to detriment in loss of earnings, must enforce promise because he cannot go back to full-time work Shoemaker v. Commonwealth Bank – shady dispute regarding lack of home insurance -court throws out claims of fraud and breach of contract, but sees at least some merit in the theory of promissory estoppel (based on detrimental reliance) -§74: if you forebear to assert a claim, that is not valid consideration unless you have good faith belief in the plausibility of the claim -promissory estoppel is not a type of contract; it is an equitable alternative theory of obligation to support agreements that lack consideration B. Restitution -originally, restitution emerged out of the theory of contracts, but in the 18th and 19th centuries it became a separate theory of obligation -quasi ex contractu: “as if it were contract” (not based on bargain; law implies the debt) -“Implied in fact” contract – like a true contract (contains actual request for services) -“Implied in law” obligation – not a contract, but restitution (“quasi-contract”) -For an implied in fact contract, there is some contractual remedy -For an implied in law obligation, there is remedy for “fair value of the benefit” -§117 of Restatement Restitution – preservation of another’s things or credit (i.e. dog) -Restitution is less about plaintiff’s harm and more about defendant’s benefit (“enrichment”) -The presumption is “you get what was promised” (but court will not enforce disproportionate promises) - Emergency cases where restitution is recognized (§116 of Restatement Restitution): 1) providing emergency services to an individual (with intent to charge) 2) where the service is necessary to prevent serious bodily harm or pain 3) when impossible for the patient to consent (unconscious or impaired) Credit Bureau Enterprises v. Pelo – mentally unstable man forcibly kept at hospital -court found that Pelo received a benefit from the hospitalization and would be unjustly enriched if he were not made to pay the amount of the bill in restitution Bloomgarden v. Coyer – referral man never asked for money first but later wanted it -because Bloomgarden never expressed an intent to be compensated until after services were rendered, court finds no obligation for restitution Violinist example: -If violinist plays outside a home and then asks for money, no claim -If violinist asks for money before playing and homeowner says no, no claim -If violinist asks for money before playing and homeowner agrees, claim of implied in fact -If violinist asks for money before playing and homeowner says nothing, claim of implied in law Mills v. Wyman – π sues for enforcement of a promise by Δ to compensate plaintiff for expenses in taking care of defendant’s 25-year-old son – promise was made after care -the court says promises based on moral obligation are not enforceable by the courts (the Δ’s son was not a minor and the promise involved no bargain or consideration, so no legal obligation) Webb v. McGowin – worker fell with wood block to save life of supervisor and was crippled as a result; sued for enforcement of oral promise to make regular payments -“where the promisee cares for, improves, and preserves the property of the promisor, though done without his request, it is sufficient consideration for the promisor’s subsequent agreement to pay for the service, b/c of material benefit” -injury to the promisee can constitute consideration even if it occurred in the past -§86: “Material benefit” or “promissory restitution” – a promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice (i.e. a suffered injury) -the promise is not binding if (1) the promisee gave the benefit to the promisor as a gift (2) the value is disproportionate to the benefit -the promisor must be the one who received the material benefit and the promisee must have at least partly intended to be compensated -If benefit is the result of acting in compliance with a pre-existing contract, no grounds for restitution -If a claimant has been acting inequitably, he cannot expect to recover on restitution theories of equity -When family members care for other family members, normally presumed to be gratuitous However, if they sacrifice substantially to care for another family member (significant time or financial expenditures, forbearance of academic, professional, or personal life, etc.), it may be grounds for promissory restitution -§86 comment (i) indicates that court has the ability to reduce the award under promissory restitution based on mitigating factors (unlike contracts: all or nothing) III. Obligation without complete agreement A. Contract/Subcontract cases In the two following government contract cases: 1) SubContractor -> submits subbid (w/ option) -> GeneralContractor 2) Project Owner <relies on subbid in big bid <General Contractor 3) Project Owner awards project to GeneralContractor based on bid 4) SubContractor revokes 5) GeneralContractor accepts subcontract (but since sub refuses, general has to hire another) -The question is whether the subbid option is binding or nonbinding James Baird Co. v. Gimbel Bros., Inc. – Judge Hand does not think that there is an option contract in this case; there does not appear to be consideration (general didn’t promise to not look for any other subcontracts); possibility of promissory estoppel, Hand says it doesn’t work because “an offer for an exchange is not meant to become a promise until a consideration has been received, either a counterpromise or whatever else is stipulated” Drennan v. Star Paving Co. – Judge Traynor differs from Hand; he says that under certain circumstances even though only one side is bound the offer is still equitable - But if sub-bid relied upon by general contractor was substantially lower than all other bids or general had reason to believe that sub’s bid was in error, there might be claim that the general should have questioned the “too good to be true” bid and not relied upon it -inequitable conduct on the part of the general would disqualify use of promissory estoppel (i.e. “bid shopping” or “bid chopping”) -time frame for general to accept sub-bid contract is very brief -§87(1): an offer is binding as an option contract if it is in writing and signed by the offeror, recites a purported consideration, and proposes an exchange on fair terms within reasonable time -§87(2) applies §90 in the specific circumstance where there is pre-acceptance -promissory estoppel is a one-way street; only the promisor can be bound -§87 applies for bilateral agreements (§45 for unilateral) -The “Drennan rule” is essentially §87(2), holding that promissory estoppel applies to pre-acceptance reliance and turns it into a binding option B. Other business transactions Pop’s Cones, Inc. v. Resorts International – Pop’s Cones was negotiating with Resorts to open a TCBY location on the boardwalk front in Atlantic City; Pop’s gave up the lease on their old location at Margate in reliance on the “advice and assurances” from Resorts -trial court found absence of a “clear and definite promise” (so no promissory estoppel) -court reverses judgment and finds such a promise, but notes that Pop’s may have difficulty proving the reasonableness of their reliance (on unwritten advice) - “expectation remedy” looks forward from breach to the benefit of the bargain - “reliance remedy” looks back from breach to circumstances before the promise -“liquidated damages” is a measure of damages contractually agreed to by parties in case of breach C. The “battle of the forms” The UCC applies whenever there is a transaction in goods §2-105 defines goods as “movable, tangible items to be sold” (intellectual property, real estate, software are all not goods) §2-104 defines a merchant as either 1) “person who regularly deals in goods of kind” 2) “person who has special knowledge or skill connected to certain goods” 3) “person who hires someone (an agent) who has special knowledge or skill connected to certain goods” §2-205 – the “firm offer” rule: under UCC certain types of options can be binding offers w/o consideration 1) The person making the offer must be a merchant 2) The offer has to be in a signed writing 3) Some indication that offer will be held open for some period of time - Under UCC, an offer that satisfies these conditions is valid when common law might not uphold the offer (conversely, if time limit expires, common law could step in to enforce agreement on basis of consideration or part performance or promissory estoppel) -in the case of an offer form provided to offeror by offeree, firm offer only activates if there is specific initialing or signing on the “firm offer” clause in addition to the contract in general -if an agreement involving goods can be upheld under UCC statute, common law does not matter -Revised §1-103(b) recognizes certain common law remedies (like promissory estoppel) -In Berryman v. Kmoch, court did not find detrimental reliance because there was no evidence that the offeror knew of or foresaw the offeree’s reliance and no evidence of any bargaining Princess Cruises v. General Electric – contract dispute after Princess forced to cancel cruises because GE needed to make further repairs and maintenance on a ship -the court finds that it was predominantly in services so applies common law instead of UCC; application of common law looks to enforce the terms of the contract between Princess and GE which limits recovery to the contract price (instead of the $4.6 million) Common law rules for forms: -“mirror image” rule – a “varying” acceptance is only a counter-offer; accepted offer must match the original offer exactly (§59) -“last shot” rule – a party impliedly assented to and accepted a counter-offer by conduct indicating lack of objection to it (the accepted counter-offer is the “last shot”, the last form sent) Old UCC §2-207 eliminated “mirror image” and “last shot” rules: -For non-merchants, only common terms between two offers are valid, unless there is specific acceptance of the new terms and conditions (favors original offer – “first shot”) -For merchants, an explicit agreement of acceptance would accept the varying terms from the second offer, unless the terms were material - “first shot” usually by weaker party, so C.L. favors stronger and UCC favors weaker Revised §2-207 is a much cleaner and fairer rule (emphasis on agreement) -Three types of scenarios that can arise where there are differences in forms/contracts: 1) Contract formed by offer and acceptance 2) Contract acceptance through performance occurs but one or both contracts are “armorplated/bulletproof” (exclusive) and thus do not otherwise establish a contract 3) Oral contract followed by at least one written confirmation that contains additional or different terms -Under New §2-207, all three scenarios are treated the same and terms of contract are: a) terms common to the two records (those non common thrown out) b) terms, in record or not, to which both parties agree (could be by conduct) c) terms supplied by a provision of the UCC (gap fillers) -§2-204: “a contract for sale of goods may be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement, including conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of such a contract” -The big three sources of agreement under UCC §1-303 (gap fillers): 1) “course of performance” – parties have made an agreement, agreement has a repeated pattern of conduct, neither party objects (i.e. installment/payment contract) 2) “course of dealing” – parties have made previous transactions and neither has objected 3) “usage of trade” – at least one party is a part of a trade that behaves in a certain way and there is a custom or behavior recognized associated with that trade -but above all else, the express terms of the contract should be superior to all three -§2-207(a)&(b) will give you express terms; §2-207(c) deals with the big three -§2-206 and §2-207: the offer documents do not have to match (if they deal w/ same thing) -agreement under §2-206 doesn’t need mirror image, but does need similar quantity/price -acquiescence or general performance will not suffice; you need agreement -UCC does have a provision on time: §2-309 says that if parties have not agreed and the record does not provide a timeframe, the standard is “reasonable time” (look to big three) -What about open terms or a preliminary agreement (“contemplated a formal contract”) Three options (determined by standard of reasonableness): 1) Memo is not enforceable at all as a contract 2) Memo is a fully enforceable contract 3) Memo is a legal obligation to negotiate in good faith Walker v. Keith – parties had an initial lease and an agreement for renewal of rent agreement but did not agree on rent -An “agreement to agree” is not a binding contract; term “reasonable rent” is indefinite -If the issue was trivial, then the court may have enforced the contract, but amount of rent is a material issue in the agreement and so should not be imposed -Most courts not inclined to “fill in the blank” when such a material provision is missing -§33 : Certainty of terms (1) Even though a manifestation of intention is intended to be understood as an offer, it cannot be accepted to form a contract unless terms of the contract are reasonably certain (2) Reasonably certain terms provide basis for determining existence of breach and appropriate remedy (3) Open terms may show that a manifestation of intention is not intended to be understood as an offer or as an acceptance - §204 – supplying an omitted essential term -Common law tends to support the more progressive flexible approach: if the agreement provides some kind of basis to calculate or fill in the missing term then the courts can enforce the agreement, but it also may be that the absence of a certain term may indicate a lack of intent to form a contract -Courts look for some evidence that the parties had “followed the path” of forming a contract -UCC §2-305 will enforce agreements that tend to indicate an intent to form a contract, even if missing terms are essential (like price); will provide more gap-fillers Contracts for more specialized products less likely to be enforced than contracts for common commodities -parties can negate the possibility of a binding agreement by explicitly stating that the preliminary agreement is not binding Quake Construction, Inc. v. American Airlines – Jones gave Quake a preliminary notice of authorization b/c Quake needed it to obtain subcontractors and stated “we reserve the right to cancel”; AA changed its mind and told Jones to terminate Quake for the project -no §33 argument because the agreement was not missing any big material terms -issue is whether language of intended contract is ambiguous -two options: either the parties intended to be bound by the letter or they did not -Judge Stamos’s concurrence presents an third alternative: parties do not intend to be fully bound but may have agreed “to negotiate in good faith” -Only a change in circumstances should give reason to completely break negotiations -Both the UCC (§2-204) and the Restatement (§27) recognize that parties may be bound contractually when they have reached agreement in principle, even though they contemplate either further negotiations (agreement to agree) or the execution of a formal written contract D. Non-paper (telephone/electronic) agreements Brower v. Gateway 2000, Inc. – π ordered a computer; included in box were terms and conditions, terms were accepted if the computer was not returned within 30 days -issue was over a term that mandated that any disputes with Gateway would have to be submitted to arbitration in Chicago -§2-207 didn’t apply because she could only reject terms by returning computer -No between both parties because there are no records from consumer; terms agreed upon by both parties would come in and gap-fillers would come in (in this case, the arbitration clause would not) -Courts have gone differently on this issue; Brower found that it would be unreasonable to hold the seller to have to confirm the oral contract other than the telephone order and the terms included in the package -§2-207: terms of contract, effect of confirmation -§2-302: question of “unconscionability” -Things have changed in the era of internet purchasing: “shrink-wrap” terms: terms included in box like Brower “click-wrap” terms: terms to which one is required to click “I agree” “browse-wrap” terms: terms made available on websites IV. Statute of Frauds -the Statute of Frauds is a barrier or shield against enforcing a contract -Three basic questions: 1) Is this a contract to which the statute of frauds would apply? (§110) 2) If it is, can I satisfy the SoF by coming up with a signed written memorandum? (§§131, 132) Only one party needs to sign – the party against whom the claim comes 3) If there is no adequate memorandum, is there a way around the statute of frauds? Exceptions: promissory estoppel (§§129, 139), part performance, and UCC exceptions -Types of contracts covered by statute of frauds (§110) a) Contract of executor or administrator to answer for a duty of his decedent b) Contract to answer for the duty of another (suretyship) c) Contract made upon consideration of marriage d) Contract for the sale of an interest in land e) Contract not to be performed within one year from the making -§110(e) is known as the “one-year provision”: if contract cannot be performed within one year without breach by either side, the statute of frauds applies -If no definite timeline, court can ask whether it is possible to perform in a year -Any contract that allows one party to terminate w/o cause is not applicable -Lifetime contracts do not fall under the provision (employee could die) -§131: General requirements of the written memorandum: (1) reasonably identifies subject matter of contract (2) sufficient to indicate that contract has been made between the parties of offered by the signer to the other party (3) states with reasonable certainty the terms of the unperformed promises in the contract -§132: the memo may consist of several writings if one is signed and the circumstances indicate that the writings “relate to the same transaction” (this is incorporated into the UCC at §1-103(b)) Two exceptions to common law statute of frauds: 1) §129 – real estate transfer action in reliance 2) §139 – general purpose promissory estoppel exception (a broader rule) -both require that reliance be reasonable, foreseeable and of a “definite and substantial character” -both require that the reliance corroborates evidence that the promise was actually made -most courts require that the reliance be proved by clear and convincing evidence -For real estate transactions (§129), if the π has changed his position significantly to his detriment in reliance on the promise covered under SoF, the courts may convey the property through specific performance -For non-real estate transactions (§139), a promissory estoppel exception to the statute of frauds will be entertained for two circumstances: 1) π detrimentally relied upon the defendant’s misrepresentation that a writing had been created that would comply with the statute 2) π similarly relied upon a promise by the defendant to create such a writing Alaska Democratic Party v. Rice – π alleges that the chair-elect offered her a two-year job that never materialized; she sues on the basis of her detrimental reliance on the oral contract -Court finds that π proved her “definite and substantial” reliance on the misrepresentation by the chair-elect of the party and thus found the contract enforceable on grounds of promissory estoppel exception for SoF -Look to UCC §2-201 for the UCC Statute of Frauds (very different than CL, $500 requirement): -§2-201(1): To meet the memo requirement you only need three things 1) Some writing sufficient to indicate that an agreement exists 2) Memo has to be signed by the party against whom the claim is brought 3) Memo has to state a quantity (not enforceable beyond the quantity stated) -§2-201(3)(a) creates an exception to the SoF for “specially manufactured goods” -§2-201(3)(b) creates an exception to the statute of frauds based on admission; π can force the Δ to admit or deny the existence of the oral agreement (if Δ admits, S of F does not apply) Even if the Δ does not explicitly admit the existence of an oral contract, the court can infer the existence of an agreement through other admissions by Δ -§2-201(3)(c) permits enforcement on the basis of “payment…made and accepted” or “goods…which have been received and accepted” If the contract is for one unit of the goods in question, part payment is sufficient -§2-201(2) defines the exception for when both parties are merchants 1) Memo does not have to be signed by the party to be charged 2) One of the merchants must send a signed confirmation within a reasonable period of time after the contract was formed (must be “sufficient against the sender” – satisfy reqs of §2-201) 3) Has to state a quantity, be signed by sending merchant, etc. -Receiving merchant then has 10 days to object after receipt of the confirmation document; if he does not, then he loses the SoF defense (loss of SoF defense, however, does not necessarily establish a contract) -§2-201(2) only applies if the written response purports itself to be a confirmation -while the confirmation is used get past the SoF, it is very likely that some or all of the terms of the confirmation will not get in under §2-207 without some other written record -the rejection of the confirmation needs to be an explicit denial of agreement, not simply an objection to some of the terms in the confirmation document -§1-202 discusses whether a party has “notice” of a written record (like the confirmation) -it is unwise for a Δ to outright deny a contract if the Δ knows that in fact an oral agreement exists, because under §2-201(3) the π can compel the Δ to admit its existence §2-201 does not have a one-year requirement – the threshold is $500 or more (rev. §2-201: $5000) GPL Treatment, Ltd. v. Louisiana-Pacific Corp. – GPL sues LA Pacific alleging breach of an alleged oral contract to buy 88 truckloads of cedar shakes -The issue is whether when a merchant seller sends a merchant buyer a writing that says “Order Confirmation” that has a “sign and return” clause, this writing constitutes a confirmation that is sufficient against the sender -Court finds that form is a confirmation writing that is sufficient against the sender: it identifies parties to the contract, prices and quantities of goods, and has GPL’s signature -Dissent found that the form constituted a mere offer, b/c of “order accepted by” line -The Convention for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) has no SoF provision V. Principles of Interpretation and Parol Evidence Rule A. Interpretation -Restatement rules for interpretation: §202 and §203 -For UCC, you can bring in basic common law interpretation principles -also look to the big three: Course of Performance, Course of Dealing, Trade Usage (to resolve an ambiguity in the express terms) -objective extrinsic evidence is ok, but subjective extrinsic evidence is not -Restatement theory: “modified objective” view (First Restatement was strictly objective) §201: Search for common understanding 1) Where the parties have attached the same meaning to a promise or term, it is interpreted according to that meaning 2) Where the parties have attached different meanings to a promise or term and neither has reason to know of the other’s meaning, no mutual assent 3) Where the parties have attached different meanings to a promise or term and one knows or has reason to know of the other’s meaning, that meaning governs 4) Where the parties have attached different meanings to a promise or term and both know or have reason to know of the other’s meaning, no mutual assent Joyner v. Adams – π brings suit for rents allegedly due under a lease contract; defendant contends that it complied with the lease contract by developing the lots -dispute is over meaning of “developed” -Trial court uses theory of interpreting against the drafter when a term is ambiguous (§206); Court of appeals says that provision does not apply because the agreement was not drafted exclusively by Joyner; it was negotiated -Court then remands for a finding of fact on whether either of the parties had reason to know of the other’s meaning Frigaliment Importing Co. v. B.N.S. – “what is chicken?” (fryers? broilers? fowl?) -since the buyer is suing, they have the burden of proving the breach -it didn’t look as though the parties had a “final integration” of their agreement so parol evidence can get it much more easily; court looks to the negotiations between the parties -One item of performance is insufficient; there must be a pattern of parts of performance and there must be acquiescence or lack of objection -Court finds for Δ because π has not met his burden of proof in proving the breach C & J Fertilizer v. Allied Mutual Insurance Co. – π brings suit for recovery for burglary loss; Δ denied coverage because there were no visible marks on building exterior -Classic case of “contract of adhesion” – you have no chance to change the terms, but only to fill in the blanks (degree of coverage, deductibles, premiums, etc.) -“The objectively reasonable expectations of applicants and intended beneficiaries regarding the terms of the insurance contracts will be honored even though painstaking study of the policy provisions would have negated those expectations” -Court finds (doctrine of reasonable expectations) that π may have reasonably anticipated that the requirement was simply evidence that it was an “outside job” -This case doesn’t quite get fully to §211, since it is not clear that the president of the company wouldn’t have accepted the coverage if he knew about the burglary clause §211 – “Standardized agreements” (like adhesion contracts) -When the other party has reason to believe that the party manifesting such assent would not do so if he knew that the writing contained a particular term, the term is not part of the agreement -UCC 1-303(e) or R §203(b) 1) Express terms first – “reasonable interpretation”, use parol evidence rule to resolve ambiguity 2) Big three: Course of performance / Course of dealing / Trade usage -Trade usage does not have to be “ancient or immemorial” as long as a majority of decent dealers follow that pattern of trade usage B. Parol Evidence Rule Parol evidence rule: §209-218 -When parties to a contract have mutually agreed to integrate a final version of their entire agreement in writing, neither party will be permitted to contradict or supplement that writing with extrinsic written or oral evidence of prior agreements or negotiations -Two questions: 1) Is the contract an integration? (Either unintegrated, partially integrated, or fully integrated) 2) What do the terms mean? -A partially integrated agreement is found to be a final expression, but not an exclusive one For part integrated, no contradiction or negation but additional consistent terms ok For full integrated, no contradiction and no supplementation -an integration requires that both parties have accepted the writing as an expression of the agreement -Two major views: classic Willistonian and more modern Corbinian (both still exist) Willistonian: plain meaning “four corners” rule, look just at the document to determine Corbinian: modified objective approach, look at extrinsic evidence to determine -both the Restatement and the UCC have embraced the Corbinian approach “merger clause” – explicit writing often used in formal agreements to indicate that the agreement is intended to be final and complete Willistonian courts would say that is undoubtedly a full integration, while Corbinian courts would find it persuasive but not conclusively a full integration -a “battle of the forms” would be an unintegrated agreement Thompson v. Libby – π brought suit for payment on logs pursuant to logging purchase agreement; Δ claims that purchase of logs was conditional on quality of the logs (a “collateral agreement”) -there was no mention of a warranty on quality in the written agreement -Court finds that agreement was integrated and therefore parol evidence regarding negotiation of a warranty was inadmissible (illustration of Willistonian approach) Taylor v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. – π brings a suit for bad faith after State Farm doesn’t settle with the other individuals involved in his accident and the damages are in excess of the insurance policy limits -State Farm claimed that Taylor had waived his bad faith claim when he signed a release -The court in AZ used Corbinian approach and considered extrinsic evidence to ascertain the intent of the parties; they find that the release could have been reasonably interpreted as Taylor assets and so finds against State Farm -Not an integration case; it doesn’t appear that either party is looking for additional terms outside -The parties are fighting instead over the meaning of the release agreement Does the term “contractual claims” include bad faith refusal to settle? -Two stages (Corbinian/Restatement approach): 1) Preliminary (Judge hears everything and filters for integration and meaning) Either unintegrated, partially integrated, or fully integrated Any contrary/negating evidence to degree of integration is thrown out 2) Determination of fact (Determination made on only admitted evidence) §214 – agreements and negotiations prior to or contemporaneous with the adoption of a writing are admissible in evidence to establish a) that the writing is or is not an integrated agreement b) that the intended agreement, if any, is completely or partially integrated c) the meaning of the writing, whether or not integrated d) illegality, fraud, duress, mistake, lack of consideration, or other invalidating cause e) ground for granting or denying some equitable remedy §216(2)(b) – the “collateral agreement” exception for consistent additional terms that might naturally be omitted from the writing §217 – where the parties to a written agreement agree orally that performance of the agreement is subject to occurrence of a stated condition, agreement is not integrated with respect to oral condition -UCC §2-202 is largely consistent with the Restatement (§§209-218) The major difference: UCC says that course of dealing/course of performance/trade usage always comes in (unless a specific express term negates one of the big three) - §1-303 hierarchy: Express Terms -> Course of Perf. -> Course of Dealing -> Trade Usage Nanakuli Paving & Rock Co. v. Shell Oil Co. – π paving company brings suit against Δ asphalt supplier, alleging that defendant breached its supply contract by refusing to price-protect after raising its prices in 1974 -no written record of price protect, but Shell had price protected twice before after a 1969 supply agreement -Express terms: No express terms of price protection Trial court did not admit preliminary negotiations -Course of performance: Had price protected twice before The court says one is not enough, but two could be Shell argues that this was not course of performance, but rather a “waiver” -Course of dealing: 1963 contract that involved price protection -Trade usage: Broad scope of trade usage – all suppliers to the asphalt paving trade on Oahu (they all gave price protection, so this is strong evidence) -Course of performance, course of dealing, and trade usage all weigh in favor -In this case, §1-202 should have been looked at (for reference to the big three) -The court in Nanakuli quotes commentary that suggests the trade usage can qualify or “cut down” express terms, but cites no case precedents (this seems a little surprising, especially since it challenges the UCC) This theory implies that express terms can shift to the bottom of the hierarchy -The court in Nanakuli also addresses a theory of good faith (UCC §1-304), finding that “both the timing of the announcement and its refusal to protect work already bid at the old price, Shell could be found to have breached the obligation of good faith.” -Majority of cases have held that promissory estoppel cannot be used to avoid the parol evidence rule -§203: “specific terms and exact terms are given greater weight than general language” -§211(3): part of parol evidence analysis (for standardized agreements) C. Implied Terms Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon - π sues for enforcement of exclusive distribution contract against Δ a fashion designer who sold her goods through other means -Appears to be an illusory promise, because Wood seemingly hasn’t agreed to do anything, simply to have exclusive rights to place Lady Duff-Gordon’s designs on sale (Lady-Duff Gordon argues lack of consideration) -Contracts are not workable unless each party takes reasonable efforts -Cardozo looks to see if contract has “business efficacy” But such efficacy requires a contract in the first place; Lady Duff-Gordon argues there never was -No §45 at this time, so Wood could not make an part performance exclusive option argument -In the UCC, we see all kinds of gap-fillers to account for implied terms §2-306(2) deals with the very issue of Wood (exclusive dealing agreement) -Seller is to use “best efforts” to provide the goods, Buyer is to use “best efforts” to promote the sale of the goods -observance of “commercially reasonable standards of fair dealing” -standard of “reasonable efforts” or “reasonable diligence” Leibel v. Raynor Manufacturing Co. – exclusive distribution contract for garage doors gave the right to terminate at any time; π alleges that termination w/ reasonable notice was an implied part of agreement -KY Court of Appeals finds that UCC applies to a distributorship agreement and that reasonable notice is required in order to terminate an on-going oral agreement for the sale of goods in a relationship of manufacturer-supplier and dealer-distributor or franchise The court doesn’t determine what defines “reasonable” -“the requirement of a reasonable notification does not relate to the method of giving notice, but to the circumstances under which the notice is given and the extent of advanced warning of termination” -In Retail Associates, Inc. v. Macy’s East, Inc. court found that ninety days notice was reasonable since there was little capital investment, inventory would turn over, and other outlets existed -§2-309(1): if not provided for or agreed upon, time for ship/deliver is “reasonable time” -§2-309(2): where contract provides for successive performances but is indefinite in duration it is valid for a reasonable time but may be terminate at any time by either party -§2-309(3): application of principles of good faith and sound commercial principles call for reasonable notice; an agreement w/o reasonable notice is invalid if unconscionable -when the parties don’t agree on the rules or can’t agree on the rules, judges become rule-setters more than umpires (the UCC pushes the courts to find the rules & standards of trade to create implied terms) -If there are explicit time terms in the agreement, a timely termination is not a violation of §2-309, but it could be a violation of §2-103 (in bad faith) -§2-306: Output, Requirements, and Exclusive Dealings Contracts involving agreements to either (1) sell all that the buyer requires or buy all that the seller produces (2) deal exclusively in the kind of goods concerned -When enforcing contracts of this type, courts apply principles of good faith Cannot be a quantity “unreasonably disproportionate” to either a stated estimate a comparable prior output or requirements Seidenberg v. Summit Bank – π sell their stock in their PA corporations to defendant in exchange for a large share of common stock in Bancorp (Δ parent corporation); π’s sue after termination -π’s allege that they had an oral understanding that if they performed well, they would retain their positions; they also allege that Δ had no intent to keep them on -Trial court looked to relative bargaining power -Court says parol evidence doesn’t bar the outside oral evidence because the plaintiffs are not offering it override express terms of the contract, but rather to offer evidence of Summit’s intent to act or not to act in good faith -The court focuses on reasonable expectations in assessing good faith and fair dealings Carma Developers – the court says that it is not in bad faith to do exactly what contract says you can do; but that discretionary power must be expressed in good faith Third Story Music – the court says that because the agreement expressly provided that Warner had the right to refrain from marketing the Waits recordings, the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing did not limit the discretion given to Warner in that regard -When you sue for breach of covenant of good faith and fair dealing, you are essentially suing for breach of contract’s implied terms (as opposed to express terms in traditional breach) Locke v. Warner Bros., Inc. – Sondra Lock case relating to agreement w/ Warner Bros. -If it were just that Warner didn’t hire her, this would not be actionable, but she alleges that they had no intention of hiring her and only had the agreement to placate Eastwood -Subjective standard – Warner doesn’t have to show that it was reasonable that it was dissatisfied with the proposed projects, only that it was honest in its dissatisfaction D. Implied duty -Standards of subjective honesty and objective observance of reasonable standards of fair dealing -Duty of good faith and fair dealing does not arise until a contract exists -Examples of bad faith conduct and meanings of good faith (chart on p449) -Sometimes the written terms of the contract are not the best representation of what the parties understand to be the agreement §1-304 – UCC good faith duty (but not designed to override express terms) -The parties may determine and specify standards that must be met -But you cannot choose standards that are manifestly unconscionable -To what extent does the good faith duty allow courts to supplement express terms? To contradict? Depends very much upon the jurisdiction -“classic discretionary clause” – right of satisfaction for one of the parties (i.e. scripts in Warner Bros.) §228: in the case where one party has the right of satisfaction over the other’s performance, there is a bifurcation (objective reasonableness vs. subjective honesty) The subjective standard should only be used when “the agreement leaves no doubt that it is only honest dissatisfaction that is meant and no more.” -In Warner Bros., Warner was not “honestly satisfied” because they had no intention of making movies from Locke’s scripts (because of pressure from Eastwood) Morin Building Products Co. v. Baystone Cosntruction, Inc. – Plaintiff company sues for breach after its aluminum siding is rejected by GM (Morin was hired by Baystone) -The big issue in Morin is to whether there is explicit language in the contract that would point the court toward subjective standard instead of objective reasonableness -Reasonable person standard is for “commercial quality, operative fitness, or mechanical utility” -Standard of good faith is for “when the contract involves personal aesthetics or fancy” -The court does explicitly refer to “artistic effect”, but the court seems to think that the artistic effect and quality fitness clauses “were not intended to cover the aesthetics of a mill-finish aluminum” wall -Posner puts a lot of emphasis on the fact that it is a form contract; no indication that the parties did extensive negotiating over the language -The at-will doctrine: unless a contact specifies at duration, it is presumed to be at-will Employee can quit at any time; employer can terminate at any time -By definition, the at-will doctrine does not apply to a contract with specified duration -The courts have been chipping away at the at-will doctrine and have created exceptions: 1) Public policy (i.e. whisteblowers) 2) Additional consideration as basis for implied “for cause” term 3) Employee handbook as basis for implied “for cause” term 4) Promissory estoppel -there is a trend toward giving more protection to employees -promissory estoppel has been more successful than the unilateral contract theory in enforcing and creating remedies for at-will contracts E. Implied Warranties -evolution from the old law “caveat emptor” rule (“let the buyer beware”); if the buyer did not specifically negotiate for guarantees of quality or fitness, there were no such warranties implied §2-313 – express warranty §2-314 – implied warranty of merchantability §2-315 – implied warranty of fitness for particular purpose (but we’re not responsible for UCC warranties this term) UCC -Two major implied warranties of common law (real estate): 1) Warranty of habitability 2) Warranty of skillful construction – “free from material defect and in a skillful manner” -most jurisdictions recognize some implied warranty of habitability -many jurisdictions also recognize an implied warranty of skillful construction in cases involving licensed professional builders (some states have statutes prescribing such warranties) -these generally don’t apply when purchasing a used home, but seller must disclose known hidden defects VI. Avoiding Enforcement -recission – cancellation of the contract and restitution (an equitable remedy) A. Capacity -one or both parties did not have the legal ability to create a contract three major categories: (1) minority/infancy, (2) mental incapacity, (3) intoxication §14 – traditional minority doctrine allows a minor to disaffirm or avoid a contract, even if there has been full performance and the minor cannot return to the adult what was received in the exchange -The minor can disaffirm while a minor or within a reasonable time of becoming an adult (Kobe) -Restitution does not apply in the case of minority (minor just has to give back the property) -only applies to contracts yet to be fully executed or fully performed -classic case is renunciation of automobile contract (minors can decide to give back car) -the normal duty is simply to give back the property received; if the contract was for services, too bad -however, minors can make binding contracts regarding “necessities” (i.e. food, shelter, medical care) §15 – Mental incapacity Two definitions of incapacity: 15(1)(a) and 15(1)(b)) -15(1)(a) deals with “cognitive” incapacity; the individual is unable to understand the nature and consequences of the transaction -15(1)(b) deals with “volitional” incapacity; the individual is unable to act in a reasonable manner in relation to the transaction and the other party has reason to know of the condition -Under 15(2), if the contract is made on fair terms and the other party is without knowledge of the mental defect, the power of avoidance terminates to the extent that the contract is so performed or the circumstances have changed and would make avoidance unjust -only the mentally incapable individual or his representative can argue to void the contract §16 – Intoxication -16(a) when individual is unable to understand the transaction (the “blotto test”) -16(b) when individual is unable to act in a reasonable manner in relation to the transaction -Both (a) and (b) only apply if the other party has reason to know that intoxication caused the incapacity -statutory decisions can make exceptions for binding enforceable contracts before 18 -the idea behind mental incapacity and intoxication is that there was no manifestation of assent B. Duress/Undue influence -a misconduct problem: one party has either interfered with the other party’s ability to make a decision or the bargaining misconduct (i.e. deception) infected the negotiating process -§174 negates voluntary assent in cases of “classic” physical duress -§175 negates voluntary assent in cases of duress by threat -(1) If assent is induced by an improper threat by the other party that leaves no reasonable alternative, the contract is voidable by the victim -(2) If assent is induced by an improper threat by one who is not a party, the contract is voidable by the victim unless the other party in good faith and without reason to know of the duress either gives value or relies materially on the transaction -§176 defines improper threats (a) threat of a crime or a tort, or what would be a crime or tort if property was obtained (b) threat of criminal prosecution (c) threat of use of civil process (suit) made in bad faith (d) threat of breach of the duty of good faith and fair dealing under an existing contract (Totem Marine Tug & Barge v. Alyeska Pipeline Service Co.) -Distinction between §174 (physical, void) and §175 (threat, voidable) duress Totem Marine Tug v. Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. – settlement agreement between Totem and Alyeska to resolve a dispute over difficulties in loading and transporting pipeline materials from TX to AK -Totem wants to void the settlement agreement on grounds of economic duress -§176(1)(d) seems to fit Totem’s claim – threat of breach of duty of good faith & fair dealing -§176(2)(b) may also fit Totem’s claim – effectiveness of threat increased by prior unfair dealing -Totem alleges that Alyeska knew of and took advantage of Totem’s dire financial situation; the settlement offer was for $97,500 and Aleyska acknowledged that they actually owed more -Totem claimed they had no alternative but to agree to the settlement -Totem would have to return the settlement payment if the agreement was voided (2-way restitution) -In Selmer Co. v. Blakeslee Midwest Co., Judge Posner found that the fact that a party agreed to a settlement because of a desperate need for cash could not be the basis for duress unless the other side had caused the financial hardship (distinct from Totem b/c Δ did not admit that it owed more than settlement) A few courts have held the opposite, that it is enough for one party to have taken advantage of the other side’s dire financial circumstances without having caused the financial hardship -In Austin Instruments v. Loral Corp., the court found that a threat to breach a contract or to withhold payment of an admitted debt has constituted a wrongful act (subcontractor attempted to extort higher price out of general contractor) -when there’s already an existing contract, the defendant doesn’t have to make the situation worse, but acting in bad faith can give rise to economic duress Undue influence – two flavors: 1) Abuse of a trusting/confidential relationship to cause a result detrimental to one party 2) Dominant person(s) overpersuading the weaker, often vulnerable, individual Odorizzi v. Bloomfield School District – Elementary school teacher seeks to void his resignation on grounds of undue influence -Court finds undue influence in dominant coercive persuasion argument -Seven factors for overpersuasion: 1) discussion of the transaction at an unusual or inappropriate time 2) consummation of the transaction at an unusual place 3) insistent demand that the business be finished immediately 4) extreme emphasis on untoward consequences of delay 5) the use of multiple persuaders by the dominant side against a single weaker side 6) absence of third-party advisers to weaker party 7) statements that there is no time to consult financial advisers or attorneys -focus on circumstances and pressure involved (don’t have to show that Δ did anything wrong)