Jesse McKinley. “New York Prisons Take an Unsavory

advertisement

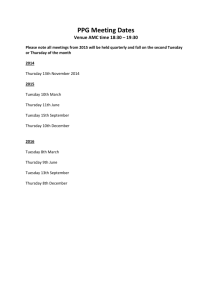

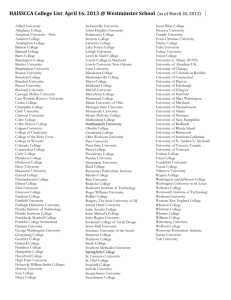

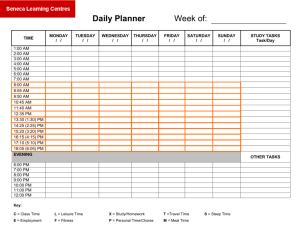

SISP 215/SOC 220: Metabolism and Technoscience Spring 2016 Tuesdays & Thursdays 1:10-2:30pm FISK 302 Instructor: Office: Office Hours: Email: Phone: Professor Anthony (Tony) Hatch 214 Allbritton (up the “Veranda”) Thursdays 3:00-4:30pm and by appointment ahatch@wesleyan.edu 860-685-3991 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will investigate the scientific idea of metabolism through the lens of technoscience. Metabolism is a flexible and mobile scientific idea, one that has been applied at the micro-level of analysis within biological organisms, the meso-level of social collectivities, and at the macro-level of global ecologies. Metabolism encompasses all of the biological and technosocial processes through which bodies (both human and not human) and societies (again, human and not) create and use nutrients, medicines, toxins, and fuels. The lens of technoscience enables us to investigate the technological and scientific practices that define and drive metabolic processes within sciences, cultures, and political economies. These processes implicate forces of production, consumption, labor, absorption, medicalization, appropriation, expansion, growth, surveillance, regulation, and enumeration. Accordingly, as we will learn, metabolism is also a profoundly political process that is inextricably linked to systems that create structural and symbolic violence as well as modes of resistance and struggle. In these contexts, we will interpret the some of the most pressing metabolic crises facing human societies including ecological disaster, industrial food regimes, metabolic health problems, and industrial-scale pollution. COURSE OBJECTIVES Comprehend core ideas within technoscience studies Apply ideas from technoscience studies to metabolic crises Evaluate the social, scientific, and ethical dimensions of metabolic crises COURSE READINGS A large number of readings are free to read online through Wesleyan’s online library. For your convenience, I have created a course pack/reader for you that contains all of the course readings, in addition to our two (2) required books: (1) John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Richard York. 2010. The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth. New York: Monthly Review Press. (2) Rachel Carson. 2012 [1962]. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1 COURSE REQUIREMENTS AND GRADING This course uses both a lecture and a student directed format where we learn from and teach each other. You will be evaluated in part on your contributions to making the class successful for yourself and others. This is a reading and writing intensive course where you will have to read and write about a large quantity of material in a relatively short period of time. This is also a course that values you as a person and respects your experience; share your brilliance and experience with everyone else! Based on these emphases, your grade is calculated out of 500 points distributed across four elements: Class Participation Reading Quizzes Reflection Papers Final Research Paper 10 percent 20 percent 30 percent 40 percent 50 points 100 points 150 points 200 points Class Participation (10 percent of your grade @ 50 pts) I expect you to attend every class, on time, prepared to engage fully in your own education. This is a dialogic course where we will engage in substantive open group discussion with daily prompting and questioning from me. I expect for you to be an active participant in every moment of every class. It’s your education. Be present for others. Be mindful of the collective space we share. I will evaluate your participation according to the following criteria. Exemplary = up to 50 points. This means you have attended every class possible (with reasonable exceptions for illness, athletics, verifiable emergencies, etc.), openly demonstrate outstanding preparedness for each class, and make significant contributions to our collective learning. Good = up to 40 points. This means you have attended most classes, demonstrate consistent preparation for each class, and make substantive contributions to our collective leaning. Fair = up to 30 points. This means you have missed about 3-4 classes, are generally prepared for each class, and make marginal contributions to our collective learning. Poor = up to 20 points. This means you are chronically late and/or absent from class, are rarely prepared for each class, and either make minimal contributions to our learning or take away from our learning. Ten (10) Reading Quizzes (20 percent of your grade @ 100 pts) In order to succeed in this class, it is essential that you complete the readings for each class as indicated on the course calendar and come to class prepared to discuss what you read. Ten (10) quizzes (10 points each) will count toward your final grade. However, we will take more than ten quizzes—I will include your ten best scores. The quizzes are based on the readings that are due that day as indicated on the course calendar. Quizzes will consist of multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank questions, true/false, and/or short answer questions. The best way to prepare for these quizzes is to read/substantively skim everything that is assigned and take reading notes that identify key terms, shifts, and content in the readings. 2 Reflection Papers (30 percent of your grade @ 150 pts) You will write three (3) reflection papers (50 points per paper; 3-4 pages each) that discuss synchronies across our course readings, lectures, and discussions within any three out of five major sections of the course. Reflections are synthetic thought statements written in the first person that signal your understanding of course content by identifying and critically assessing patterns in the content, themes, and questions that cut across our course. Your job is to engage directly with information you found especially compelling, problematic, or inspiring. As you make decisions about what to reflect on, consider that you will have the option of incorporating selected text from your reflections into your final research paper. Aside from these considerations, each reflection must do the following: a) Substantively interrogate (e.g., raise and answer questions about) multiple course readings from within that part of the course b) Connect your interrogation multiple lectures and/or in-class discussions from within that part of the course c) Incorporate and examine your own thoughts, interpretations, feelings, beliefs, practices on the issues raised in the readings, lectures, and discussions. d) Be no less than three (3) and no more than four (4) full pages in length. Each paper needs to be double-spaced, with 1-inch margins, and 12-point font with your name, course name, response number, and the date typed single-spaced at the top of the page. I will deduct five (5) points automatically for improperly formatted papers. Please include footnotes with complete citations when appropriate. Reflection Paper Due Dates: You will select any three major parts of the course (I through V) and turn in a reflection paper about each part of the course on the first day of the next part. For example, a reflection paper based on Part I of the course is due on Tuesday, February 2. Reflection papers written about part V of the course are due on the last day of classes (with no exceptions). Please print out and turn in your response papers at the beginning of the class. Unexcused late reflection papers will lose five (5) points per day of lateness (starting the day of class they were due). Final Research Paper (40 percent of your grade @ 200 points) You will write one ten (10) page research paper that uses an analytic framework of technoscience to investigate a specific social, cultural, or scientific problem related to metabolism. We will discuss the instructions for the final research paper assignment later in the course. I strongly encourage you to make regular use of my office hours to discuss this assignment. I will make myself available during the reading period for extra help with your papers. Proposal Due Date: A one (1) page proposal for the paper is due on Tuesday, April 12 that informs me of your provisional thinking. Upload your completed proposal to Moodle before class. This proposal is worth 25 points out of 200 for the final research paper. I prefer clearly articulated and well conceived proposals to thin and muddled proposals. Paper Due Date: 5:00pm on Wednesday, May 11th in Moodle. 3 GRADING SCALE Percent 97-100 93-96 90-92 87-89 83-86 80-82 77-79 73-76 70-72 67-69 63-66 60-63 57-59 53-56 50-52 47-49 44-46 40-43 below 40 Points 485-500 465-484 450-464 435-449 415-434 400-414 385-399 365-384 350-364 335-349 315-334 300-314 285-299 265-284 250-264 235-249 220-234 200-219 below 200 Grade A+ A AB+ B BC+ C CD+ D DF+ F FE+ E EF OTHER VERY IMPORTANT COURSE INFORMATION This course requires a high level of student preparedness and endurance. I do not expect this to be an easy course, but I do expect it to be an engaging, enriching, and empowering one. Please review the following information, as it is essential to your success. You are responsible for all of the information that follows—please consult the syllabus before you email me with questions about course policies. DISCLAIMER This syllabus provides a general plan for the course: deviations may be necessary. HOW TO CONTACT ME Please email me with any questions or concerns about the class, but please note that I only read and respond to student emails during normal business hours (9-5, M-F) except in rare cases of actual emergency. Please allow 1-2 days for an email response from me for non-urgent issues. Be sure to review the syllabus carefully before emailing me about course policies. I would also love to see you during my office hours on Thursdays 3:00-4:30pm and by appointment. Please have respect for the fact that I’m a writer and work in my office everyday. If you come to my office unannounced, I will politely ask you to come on Thursday or to email me for an appointment. 4 EXTRA CREDIT I reserve the right to offer extra credit during the semester at my discretion. I also reserve the right not to offer extra credit. LATE WORK WE TAKE QUIZZES WITHIN THE FIRST 10-15 MINUTES OF CLASS—YOU WILL NOT BE ABLE TO MAKE UP QUIZZES IF YOU ARE LATE! READ THAT AGAIN. If you have an excused absence from class when we take a quiz, you can make up your quiz during my weekly office hours (Thursdays 3-4:30). I will not hunt you down asking you to make up your work—it is your responsibility to keep me informed about your work. Unexcused late reflection papers will lose five (5) points per day of lateness (starting the day of class they were due). I retain the right to offer and/or deny make-ups based on my assessment of your situation and any relevant documentation. USING MOODLE I will make regular use of Moodle’s “News” feature to communicate with the entire class. It is your responsibility to monitor Moodle regularly for any important announcements! TECHNOLOGY USE IN CLASS You are NOT permitted to use laptops, smart phones, or tablets during class without explicit permission from me. Explicit permission from me looks like you signing a written pledge to only use note-taking applications on a laptop or tablet. We are in class for 1 hour and 20 minutes each day— this is exceptionally valuable time in our lives and I’d rather not waste it with you being in two or more digital “places” while you are with us. Using devices during class is disruptive to the class and disrespectful to me personally. Be digitally unavailable to your people during class time (that’s what I do). Be on notice: I favor public humiliation if you violate this ethic. However, if you must make or take an EMERGENCY phone call during class, please step outside to do so. ACADEMIC DISHONESTY IS SERIOUS I treat all forms of academic honesty with the utmost seriousness and strongly encourage you to comply with Wesleyan’s Honor Code which you can review within the student handbook (http://www.wesleyan.edu/studentaffairs/studenthandbook/20152016studenthandbook.pdf) Violations of the Honor Code may result in an F in the course and possible academic and disciplinary action. All violations will be reported without exception. DISABILITY RESOURCES Wesleyan University is committed to ensuring that all qualified students with disabilities are afforded an equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from its programs and services. To receive 5 accommodations, a student must have a documented disability as defined by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, and provide documentation of the disability. Since accommodations may require early planning and generally are not provided retroactively, please contact Disability Resources as soon as possible. If you believe that you might need accommodations for a disability, please contact Dean Patey in Disability Resources, located in North College, Room 021, or call 860/685-5581 for an appointment to discuss your needs and the process for requesting accommodations. COURSE EVALUATION Your honest and constructive assessment of this course plays an indispensable role in shaping the future of education at Wesleyan and my prospects for future employment here (for real). Upon completing this course, please take time to fill out the online course evaluation. COURSE CALENDAR 1. Thursday, January 21: Introduction and Syllabus Part I: Theorizing Technoscience 2. Tuesday, January 26: Feminist Technoscience Studies Donna J. Haraway. 1997. “Syntactics: The Grammar of Feminism and Technoscience,” pp. 1-20 in Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan₋Meets₋OncoMouse: Feminism and technoscience. New York: Routledge. Sandra J. Harding. 2015. “New Citizens, New Societies: New Sciences, New Philosophies?” pp. 1-25 in Objectivity and Diversity: Another Logic of Scientific Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 3. Thursday, January 28: Political Sociology of Science Scott Frickel and Kelly Moore. 2006. “Prospects and Challenges for a New Political Sociology of Science,” pp. 3-34 in The New Political Sociology of Science: Institutions, Networks, and Power. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Shelia Jasanoff. 2004. “Ordering Knowledge, Ordering Society,” pp. 13-46 in States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. New York: Routledge. Part II: The Ecological Rift 4. Tuesday, February 2: The Ecological Rift John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Richard York. 2010. The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth. New York: Monthly Review Press. (Wesleyan Online Library), read Part I 6 5. Thursday, February 4: The Ecological Rift The Ecological Rift, read Part II 6. Tuesday, February 9: The Ecological Rift The Ecological Rift, read Part III Part III: Food Regimes 7. Thursday, February 11: Food Regimes Harriet Friedmann. 1993. The political economy of food: A global crisis. New Left Review (197): 2957. Phillip D. McMichael. 2009. “A food regime genealogy.” Journal of Peasant Studies. 36:139-169. 8. Tuesday, February 16: Food Security Eric Holt-Giménez. 2001. “Food Security, Food Justice, or Food Sovereignty? Crises, Food Movements, and Regime Change,” pp. 309-330 in Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability (Edited by Alison Hope Alkron and Julian Agyeman) Cambridge: The MIT Press. (Wesleyan Online Library) Kari Marie Norgaard, Ron Reed, and Carolina Van Horn. 2001. “A Continuing Legacy: Institutional Racism, Hunger, and Nutritional Justice on the Klamath,” pp. 23-46 in Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability (Edited by Alison Hope Alkron and Julian Agyeman) Cambridge: The MIT Press. (Wesleyan Online Library) 9. Thursday, February 18: Agricultural Labor Seth Holmes. 2013. “Because They’re Lower to the Ground: Naturalizing Social Suffering,” pp. 155181 in Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) Timothy Pachirat. 2013. “Es todo por hoy,” pp. 85-108 in Every Twelve Seconds: Industrialized Slaughter and the Politics of Sight. New Haven: Yale University Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) 10. Tuesday, February 23: Food Safety Marion Nestle (2010). “Peddling Dreams: Promises Versus Realities,” pp. 145-166 in Safe Food: The Politics of Food Safety. Berkeley: University of California Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) Bruce M. Chassy. 2015 “Food Safety,” pp. 587-614 in The Oxford Handbook of Food, Politics, and Society (Edited by Ronald J. Herring). New York: Oxford University Press. 7 11. Thursday, February 25: Techno-foods Anthony Winson. 2013. “The Spatial Colonization of the Industrial Diet: The Supermarket,” pp. 184-205 in The Industrial Diet: The Degradation of Food and the Struggle for Healthy Eating. New York: New York University Press. (Wesleyan Online Library) Marion Nestle. 2007. “Beyond Fortification: Making Foods Functional,” pp. 315-337 in Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. Berkeley: University of California Press. 12. Tuesday, March 1: Fuels and Climate Change Phillip D. McMichael. 2010. “Agrofuels in the food regime.” Journal of Peasant Studies 37:609-629. Derrill D. Watson II. 2015. “Climate Change and Agriculture: Countering Doomsday Scenarios,” pp. 453-474 in The Oxford Handbook of Food, Politics, and Society (Edited by Ronald J. Herring). New York: Oxford University Press. 13. Thursday, March 3: Cannibalism Cormac O. Gráda. 2015. “Eating People is Wrong: Famine’s Other Secret?” pp. 11-37 in Eating People is Wrong, and Other Essays on Famine, Its Past and Its Future. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) Vincent Woodward (2014). “Cannibalism in Transatlantic Context,” pp. 29-57 in The Delectable Negro: Human Consumption and Homoeroticism with US Slave Culture (Edited by Justin A. Joyce and Dwight McBride). New York: New York University Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) Spring Break: March 7 - March 18 Part IV: Health Sciences and Medicine 14. Tuesday, March 22: Nutritionism & Nutritionalization Jane Dixon. 2009. From the imperial to the empty calorie: How nutrition relations underpin food regime transitions. Agriculture and Human Values 26 (4): 321-33. Gyorgy Scrinis. 2013. “A Clash of Nutritional Ideologies,” in Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice. New York: Columbia University Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) 15. Thursday, March 24: Epigenetics Hannah Landecker. 2011. Food as exposure: Nutritional epigenetics and the new metabolism. Biosocieties 6 (2): 167-94. Hannah Landecker and Aaron Panofsky. 2013. From social structure to gene regulation, and back: A critical introduction to environmental epigenetics for sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 39: 333-57. 8 16. Tuesday, March 29: Sugar Sidney Mintz. 1986. “Sugar and Morality,” pp. 67-83 in Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom. Boston: Beacon Press. Anthony R. Hatch. 2016. “Sugar Stained with Blood: African Americans, Sugar, and Modern Agriculture,” in Blood Sugar: Racial Pharmacology and Food Justice in Black America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 17. Thursday, March 31: Fatness/Thinness Charlotte Biltekoff. 2013. “Thinness as Health, Self-Control, and Citizenship,” pp. 109-149 in Eating Right in America: The Cultural Politics of Food and Health. Duke University Press. (Requested from Conn College) Reading TBA 18. Tuesday, April 5: Diabetes Chris Feudtner. 2015. “Irony in an Era of Medical Marvels: Diabetes History as a Study of Health and Hope,” pp. 3-32 in Bittersweet: Diabetes, Insulin, and the Transformation of Illness. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) Michael Montoya. 2011. “Genes and Disease on the U.S.-Mexico Border: The Science of State Formation in Diabetes Research,” pp. 69-90 in Making the Mexican Diabetic: Race, Science, and the Genetics of Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) 19. Thursday, April 7: Organic Alternatives Wenonah Hauter. 2012. “Organic Food: The Paradox,” pp. 98-116 in Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America. New York: The New Press. Tomas Larsson. 2015. “The Rise of Organic Foods Movement as a Transnational Phenomenon,” pp. 739-754 in The Oxford Handbook of Food, Politics, and Society (Edited by Ronald J. Herring). New York: Oxford University Press. 20. Tuesday, April 12: Milk Andrea S. Wiley. 2014. “Milk as Children’s Food: Growth and the Meanings of Milk for Children,” pp. 113-146 in Cultures of Milk: The Biology and Meaning of Diary Products in the United States and India. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Wenonah Hauter. 2012. “Milking the System,” pp. 211-226 in Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America. New York: The New Press. ***Proposal for your final research paper is due 9 21. Thursday, April 14: Prison Food Jesse McKinley. “New York Prisons Take an Unsavory Punishment Off the Table,” New York Times, December 17, 2015. Reading TBA Part V: Environmental Toxicology & Industrial Pollution 22. Tuesday, April 19: Silent Spring I Rachel Carson. 2012/1962. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, Chapters 1-9 23. Thursday, April 21: Silent Spring II Rachel Carson. 2012/1962. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, Chapters 10-17 24. Tuesday, April 26: Pesticides Jill Harrison. 2011. “Assessing the Scope and Severity of Pesticide Drift,” 25-50 in Pesticide Drift and the Pursuit of Environmental Justice. Cambridge: The MIT Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) 25. Thursday, April 28: Complexities of Toxicology Michelle Murphy. 2006. “Indoor Pollution at the Encounter of Toxicology and Popular Epidemiology,” pp. 81-110 in Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers. Durham: Duke University Press. Sara Shostak. 2013. “Toxicology is a Political Science,” pp. 23-47 in Exposed Science: Genes, the Environment, and the Politics of Population Health. Berkeley: University of California Press. (Wesleyan Library Online) 26. Tuesday, May 3: Last Day of Class Wednesday, May 11 @ 5pm Final Research Papers Due in Moodle. 10