File - The Portfolio of Luke Hughes

advertisement

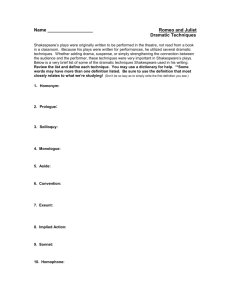

1 Hughes Luke Hughes Dr. Hadorn Shakespeare 11/27/13 Teaching Shakespeare One of the most challenging subjects to teach to high school students is Shakespeare. Immediately, the students are groaning and complaining about having to read and discuss Shakespeare. “Shakespeare is boring. Shakespeare is too long. The language is too hard to read. Shakespeare is so dated. Who cares what he has to say anymore?” Unfortunately, some of these claims have validity to them. His plays were written for a different time, the stories told are old, and the language is very difficult to understand, especially if one has never read Shakespeare before. But there are important points that need to be remembered in order to want to teach Shakespeare. A Shakespeare play is not just a story to be read through, but an observation of humanity and morality. His plays are so convertible and adaptable, that they can still be put on in theaters today. That means something. The survivability of his plays is remarkable enough to teach about Shakespeare, but it is deeper than that. He gives us the opportunity to evaluate his plays and in doing so, evaluate ourselves. A teacher has to understand this and needs to enthrall the students and make Shakespeare accessible in order to teach these ideas. In order to teach a Shakespeare play, the teacher needs to address certain issues in order to ensure that his or her students understand Shakespeare. Tackling the length of the plays, breaking through the language barrier, displaying clearly the core concepts of any play, and shedding light on the more subtle concepts that can be easily missed are all vital components to properly teaching Shakespeare. 2 Hughes Shakespeare’s plays have an immediate inaccessibility due to their length. Students see this as a daunting task and struggle to become motivated enough to begin reading. In an interview with a former teacher of mine, Dr. Alexander George of Marmion Academy, I was told that there are a few tricks and resources that I can use in order to make it understandable and condensed so that as the class moves forward with the readings, no one is left behind and everyone is on the same page. In order to overcome the fear of reading such a long piece of literature, students should go at in piece work. Assigning a few acts can instill a feeling of dread. Instead reading a few scenes and addressing what was read the next day allows the students the ability to read at an easy pace and also gives the teacher an opportunity to have really in depth discussions about the material read. Another idea that helps is to show a production of the play after each act read. This breaks up the reading, gives the students a visual of what the characters and action looks like, and it can clear up any questions about what actually happens in the play. Having a CD of the play or finding a reading online can help with the reading as well. Reading the play is one thing, but understanding the difficult language of Shakespeare is a completely different task altogether (Nov. 15). Why is it important to understand the language of Shakespeare? Isn’t it enough to just read through it for face value or to just know that in the end of Romeo and Juliet, the two lovers will die? The answer is no. Shakespeare’s language is essential to understanding not only the plays, but the time and culture that Shakespeare wrote in. Simply put, “Shakespeare is part and parcel of English-speaking culture, and not only high culture” (Belsey, 1). Shakespeare’s language is unique, complex, and layered with alternate meanings and hidden messages. His “vocabulary is immense, his linguistic innovations way in excess of other writers’, while the 3 Hughes sheer density of the imagery can be breathtaking” (Belsey, 9). To simply gloss over a play is to do a disservice to Shakespeare and to the students as well. Even if his language is prolific, it is still very difficult to read. There are a few problems with his language that can make a new reader apprehensive in reading Shakespeare. George R. Price states that “Shakespeare’s use of words that are now obsolete” as well as his “use of words which are identical in form with familiar words of today, but which had a different meaning in Shakespeare’s time” are barriers that can squash a desire to read Shakespeare. Price offers a few tips to help remedy these problems, such as looking through the glossarial notes and putting a dot underneath each word that has a note attached to it so they know to look for a meaning in the notes (12). According to Dr. George, having the students read the Sparknotes summary can also be a big help in letting the student know what is happening in the play as they read along, even if the language is difficult to understand. This makes sure that everyone knows the basics of a play and ensures that no one will be surprised by questions about what occurred in the play on an exam. It is worth noting that students should not read the analysis that Sparknotes offers. It is the students job to analyze the action of the play and normally the analyses are unreliable and incorrect (Nov. 15). Another tactic that is worth noting is to have the students perform a portion of the play. What this does is break up the repetition of reading as well as give the students an opportunity to practice the language. First, a film version or recorded production of the play should be performed. This allows students the chance to see how the actors on stage read the lines. It shows how the words are said, but also shows with what emotions the actors say them with and how the other characters react to these words. It is vital to learn the vocabulary and become familiar with it as “vocabulary is the raw material of character building” (Noble, 99). If there were no past 4 Hughes performances of Shakespeare’s plays and all that was available were the texts, the vocabulary and dialogue would be the only information that could define what a character looks and acts like. By performing scenes from the play, students will have to access the meaning behind the lines and other students will be able to see how the characters treat each other. The teacher needs help his or her students through the dialogue, but doing this will give the students much more insight into the minds of the characters as well as Shakespeare’s intentions in having the characters act a certain way. Once the vocabulary, wording, and dialogue are out of the way, the next obstacle is the actual content. Shakespeare’s plays are intricate and finding the themes within them can be a challenge. The teacher needs to update his or her understanding of whatever play is being taught and needs to remember to modernize it so that the students can more easily attach themselves to the story. An example of this would be to make connections the anti-Semitic attitudes of The Merchant of Venice to the more modern anti-Islamic feelings of today. As stated in Greenblatt’s Shakespeare’s Freedom, “the two principal historical enemies of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, succeed each other so easily in the imaginative structure created by Shakespeare’s comedy of friendship and enmity” (53). It isn’t difficult to substitute one hatred for another. It provides the teacher the chance to show how this hatred is unfounded and also helps to humanize Shylock. Hatred, mercy, and justice are a few of the main themes in The Merchant of Venice and showing how these themes carry over to the present day lets the students have some background so that they can contribute to a discussion. The themes become clearer and students can also have an idea as to what the times of Shakespeare were like. It is also important to explain Shylock’s hatred of Antonio in order to show why Shylock is considered the villain in this play. Looking to history can serve many purposes at this point. 5 Hughes Throughout history, Jews were blamed for the death of Jesus and the Christians never let them forget this. Crusades, riots, and murders were performed to rid the Christians of the “Jewish scourge” that plagued them. A teacher could point to various historical instances of prejudice and crimes performed against Jews for simply being Jewish. The Christians put Jews through many humiliating and horrific trials to try to minimize them, such as putting the Jews in “the ghetto and [forcing them into] an economic life restricted to moneylending and the gabardine with the yellow badge” (Greenblatt, 62-63). This gives reasoning behind Shylock’s general hatred for Christians and makes his hatred seem justified and more real. Of course, the teacher needs to also explain why Shylock hates Antonio on such a personal level as well and to do that, the teacher needs to pull directly from the text. Using key lines such as “You call me misbeliever, cut-throat, dog,/ And spit upon my Jewish gabardine” (1.3.111-112, The Merchant of Venice) to point out the misdeeds that Antonio has done to Shylock explains and justifies his hatred better than just simply explaining it away as an ancient hatred. The teacher can then personalize this and ask how the students would feel if someone did this to them because of something they believed in. By doing so, the students can begin to sympathize with Shylock and see how his hatred fuels him to make the flesh bond. Showing a production of the play can also cement the sympathetic view of Shylock and also shows how the other characters treat him. Themes like hatred in The Merchant of Venice are easy to teach as they are right in the open and many texts talk about them, but what about more subtle themes like disguise? How does a teacher explain disguise when most students read it and do not think anything of it? Disguise is a common concept that most people know about, so what is so special about it? In Shakespeare’s plays, however, disguise is extremely important to plot development as well as 6 Hughes showing how some women only become empowered when they become men. A theme as important as this one needs to be noticed, so what is a teacher supposed to do in order to draw the students’ eye towards its importance? Explaining disguise in Shakespeare’s plays is a good idea to help establish the idea of disguise and its frequent use in his plays. According to Muriel Bradbrook on Shakespeare, there are five main types including “the girl-page… the boy bride… the rogue in a variety of disguises… the spy in disguise… and the lover in disguise” (Bradbrook, 21). Giving an example of each of these disguises in other Shakespeare plays and explaining what happens when each character is in disguise can give the students a better idea of the power disguise contains in the plays. Another good starting point is to point out the changes the same character experiences when they put on the disguise. Portia’s transformation from a damsel in distress to a learned lawyer shows that the donning of the male disguise empowers her and gives her the ability to change the outcome of a dire situation. What this does is show the students how a disguise changes a character and allows them to do something that they normally wouldn’t be able to. Of course this isn’t enough. Students need something that they are familiar with in order to make connections and understand concepts. The easiest way to do this with disguises is to compare them to superheroes and their powers when they are disguised. There is not a single person in the world that has no idea who a superhero is. They are powerless when not in their costumes, but as soon as they put on the outfit, they undergo a transformation that allows them to accomplish anything. Comparing Portia’s disguise to Peter Parker’s Spiderman costume may be corny and cheesy, but it is a fair comparison and students will have no choice but to understand the power of disguise. Again, by attaching themes to the modern day and to students’ lives, Shakespeare becomes simpler and easier to learn. 7 Hughes Teacher’s need to understand that while teaching Shakespeare may be difficult, learning it is even harder. Shakespeare is a subject that every student dreads, but every student needs as well. Through breaking up the length of the plays, deciphering the language, presenting the main themes of the plays in familiar terms, and by revealing the underlying and subtle themes present in his plays, Shakespeare becomes accessible and a pleasure to read. It is impossible to understand past and modern culture without understanding Shakespeare. If a teacher can understand this importance, then teaching Shakespeare becomes more than a lesson. It becomes a part of the teacher’s life. 8 Hughes Works Cited Bradbrook, Muriel. Muriel Bradbrook on Shakespeare. New Jersey: Barnes and Noble Books, 1984. Print. Belsey, Catherine. Why Shakespeare?. New York: Palgrove Macmillan, 2007. Print. George, Alexander PhD. Personal Interview. 15 Nov. 2013. Greenblatt, Stephen. Shakespeare’s Freedom. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago, 2010. Print. Noble, Adrian. How to do Shakespeare. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print. Paris, James F., and Ronald E. Salomone, eds. Teaching Shakespeare into the Twenty-First Century. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1997. Print. Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Trans. Anne Barton. The Riverside Shakespeare: The Complete Works. 2nd ed. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans and J.J.M. Tobin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997. p. 293. Print. 9 Hughes Power Lines: Tracing power in relationships throughout the Merchant of Venice Description and Reasoning: Students will: Examine how power is used in relationships. Examine the connections between power and money. Enact situations similar to those in the play. Materials: Handout: Instructions for Status Game Deck of playing cards Scenario cards Handout: Tableaux assignments Performance evaluation Rubric Folger editions of The Merchant of Venice Digital camera (optional) Documents: o Status Game Instructions o Scenarios o Tableaux assignments Procedure: Day 1: 1. Discuss the concept of status with the class. How is it defined? What does it mean in life, school etc? How is it demonstrated in body language, voice, etc? 2. Have the class play the Status Game, using the instructions on the Handout. 3. After the game, to reinforce the concept of staus and power in specific settings, divide the class into small groups and distribute a scenario card to each group (some scenarios may be repeated if class size is large). 4. Have each group act out the scenario on their card. All students should participate. 5. Advise students that they should consider setting, characters and give their scene a structure (beginning, middle and end). 6. Give students about five minutes to brainstorm, followed by fifteen minutes rehearsal time. 7. Have students perform their scenes to the class. 8. After the performances, have students write a journal entry, addressing the following questions: Which person in each scene had the greatest status or power? What is the difference between status and power? Why? How was this made evident? What gave one person power over another? 9. Discuss the class' findings. 10 Hughes 10. Explain that the scenarios are similar to the events in the play. As the play progresses, characters may gain or lose power depending on their actions and the actions of others. Day 2: 1. Divide students into small groups. 2. Assign each group a scene from Handout of Tableaux assignments (each scene contains a moment when the power structure shifts). 3. Have students read over their scene together and decide how they could represent the power structure in the scene through a living picture or Tableaux Vivant. For this activity: Students select a pose that represents their scene and freeze. Students create at least two living snapshots, one showing the power structure at the beginning of the scene, and another showing the power structure at the end of the scene (or wherever the power shifts). Students should consider how body language can denote power relationships and alter their positions accordingly. To accompany each tableau, students should select a set of lines from the scene to recite before moving to the next living picture. These lines should come directly from the text and should reflect the shift in power. The lines can be recited by one member of the group or chorally. Each group reads a line, freezes into their snapshot, repeats the process for a second snapshot. Students should discuss and prepare to share their ideas on what they think Shakespeare was trying to illustrate about the theme of power in these scenes. Have each group perform its tableaux. One option would be to take digital photos throughout the performance to provide a visual reminder of the balance of power shifts through the scene. Adapted from Melanie Whiteley’s lesson plan on www.folger.edu. 11 Hughes Can’t Buy Me Love Description and Reasoning: One of the reasons The Merchant of Venice is so interesting—and so troublesome—is that characters in Venice cannot define human values such as justice, mercy, and love in anything other than economic terms. The language of the Venetian characters is fraught with terms of economic rather than romantic exchange. This activity emphasizes finding the multiplicity of meanings buried within Shakespeare's language. Students will examine how the meanings of words differ in Belmont and in Venice. Materials: Copy of The Merchant of Venice. Documents o Can't Buy Me Love Handout. o Links: Shakespeare Concordance. Procedure: 1. Divide students into groups of three or four. Assign four words from the following list to each group: fortune, value, interest, worth, engaged, bond, dear, gold(en), good(s), hazard. Give each student the attached handout, and have them copy their assigned words onto the chart. 2. In their groups, have students search for their assigned words using an online Shakespeare concordance. What different meanings do these words have in different contexts throughout the play? Do they have different meanings in Belmont and in Venice? Have them fill in the Belmontian and Venetian meanings of the words in the chart. They may use a dictionary to help them. 3. Next, have each group choose one of their four words and a scene in which it appears. Have them discuss the following questions as a group. Each group should choose a scribe who will write down the answers. Where does this scene take place? Which characters are speaking? Where are they from? To whom are they speaking? How do the other characters understand what the speakers are saying? Are characters from different places able to understand one another? Then, have students repeat this activity with one more of their words. 4. Have each group present their findings to the class. Conclude with a discussion about how language is used differently by characters in different places. Does this change the students' view of the play in any way? 5. As a concluding activity, have students act out their scenes. Adapted from Heidi Beehler’s lesson plan on www.folger.edu. 12 Hughes Complexity of Character in The Merchant of Venice Description and Reasoning: The goal of this assigment is for students to explore ambiguity by discovering the intricacy present in many of the characters in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. Students will: Perform a speech of a chosen character multiple times Research past portrayals of this character on stage and on film Evaluate how the varied portrayals of a character reflect that character’s complexity. Materials: Copies of the respective speeches or of the play (for each student) Handout #1 Image Analysis(one per group) Computer access (at least one per group) Poster paper Markers Space Optional Materials: Film versions of the plays Reference books: Dictionaries, A Shakespeare Glossary, C.T Onions Shakespeare's Lexicon and Quotation Dictionary, Schmidt Multiple editions of the text Shakespeare Set Free - especially the essay on close reading by Michael Tolaydo, p.27 in Macbeth, A Midsummer, Night' Dream and Romeo and Juliet edition. Documents: Image Analysis Procedure: Day 1: 1. Assign each group (or let each group choose) one of the following characters and their accompanying speeches/lines. All citations refer to the Folger edition of the play. Portia-1.2.12-26, OR 3.2.153-178 b. Bassanio- 3.2.261-282 c. Antonio-4.1.276-293 d. Shylock- 1.3.116-139 OR 3.1.52-72 e. Lorenzo-5.1.57-76 f. Jessica- 2.3.1-9 AND 2.3.15-21 g. Lancelot- 2.2.1-31 2. Have students sit in a circle in their groups. Ask each group to read their character's speech by having one student start and read to the end of a final stop (period, question mark, exclamation point, semicolon, or colon) then rotating around the circle as necessary until the entire speech has been read. As the speech is being read this time, 13 Hughes 3. 4. 5. 6. students should circle any words they do not fully understand. After the first reading, discuss these words, consulting references as necessary. Have students write a one sentence summary that explains what is going on in their assigned speech. Ask students to read the same speech again in their groups, this time chorally (everyone reading in unison). As they read, they should consider what their character's motivation might be for saying each word or line. After the choral reading, have students go through the speech and make marginal notes, identifying the reason their character is saying the line. To assist, have them think about what the character is trying to accomplish or hoping to gain by his speech. Ask students to divide their character's speech into logical chunks based on the number of members in the group. Each group member then reads an assigned chunk in order so that the group is essentially reading the speech a third time. As they read, they should consider how the character would deliver the speech-- tone, gestures, movements, vocal stresses, props, etc. Have students discuss these choices after reading the speech this third time with their group. Have students plan a group performance of their speech. Each group should perform their speech to the class in such a way that every group member has lines to speak (either chorally or individually) and that the scene is staged to reflect what is being said. Have each group perform the speech to the class. The group should not explain anything about their performance choices before or immediately after their performance. Tell the class who the character is before the group performs. After the performance, have the class brainstorm a list of character traits they noticed in the character being presented for performance. Jot these traits down on a poster under the character's name. Do this after every performance. Keep these posters to revisit in a few days. Day 2: 7. Have students research images at luna.folger.edu of how their characters have been portrayed in past productions or artistic interpretations of the play. Students should reference at least 3 images (paintings, promptbooks, costume drawings, photographs, etc.) from as many time periods as possible. For each image they should choose at least 2 details in the image and explain how these details reflect their assigned character as complex (See Handout 1: Image Analysis) 8. For homework, have students view how their character is portrayed in a production of the play using YouTube video clips. Another option would be to show a portion (or more than one) of a film version of the play in class and have each group focus on its own character as they watch. Students should consider how the actor plays the character and how that portrayal can be justified in Shakespeare's text. Day 3: 9. Give students a clean copy of their respective speeches. Have students re-annotate their assigned speeches for performance, given all their research. They should consider how their original interpretation has/has not changed as a result of their research. Allow them 14 Hughes time to make up to 5 changes to their performance which must be justified by their image and video research. 10. Have each group perform again. As before, make a list of descriptors on a poster. Compare this to the original list and discuss how different performance choices were made and why. 11. Lead a reflective discussion by having students stand in a circle. Give them a minute to complete the following sentence in relation to the last few days' work. "I noticed...." Go around the circle so that every student has a say. 12. Do 3 more rounds using the following sentence starters: "I appreciated..." "I learned..." 13. As a follow up activity, assign students a different speech from a different play and have them identify the complexities in the character by annotating the speech as they did on Day 1, keeping in mind how their character might be portrayed visually in art, film or on stage. Adapted from Christina Alvarez’s lesson plan from www.folger.edu. 15 Hughes Interviewing the Suspects Description and Reasoning: If you watched the news once, you’ve probably seen some sort of impromptu interview with someone in some sort of court setting. You’ve probably seen them leaving the courtroom and being bombarded with questions and camera flashes. What this lesson plan is hoping to do is slow this down and make it more personal. People will be separated into groups and assigned to roles of the characters in the courtroom of The Merchant of Venice. There will be one reporter who will interview each of the characters and report their stories to the editor (the teacher). Students will be able to understand better the action of the courtroom as well as perhaps understand the feelings and resentments that the characters have towards one another. The reporters will ask important questions and practice critical thinking skills in coming up with questions while the court room characters will dive into the minds of the characters of the play and also practice their critical thinking in coming up with responses. Materials: Notebook and Pen Copy of The Merchant of Venice for reference Procedure: 1. Divide the students into groups of 4 or 5. 2. Have them pull names out of a hat to see who they will be playing during this activity. 3. Whoever pulls the reporter slip out of the hat will have 3-5 minutes to write down some questions to ask. They can ask the teacher for help in figuring out what is important to ask. During this time, the students that pulled character slips out of the hat can review what happened in the courtroom and try to imagine the mentality of these characters. 4. For about 15 minutes, the reporter will interview each of the characters. The questions asked should be basic at first, asking what happened in the courtroom and whether or not the outcome was desired. Later they should get more difficult, asking specifics like “I heard that you were offered three times the amount of ducats loaned? Why didn’t you take that instead?” and the student acting as Shylock would have to explain his or her decision. They will write down their responses and keep interviewing. The characters should answer the questions honestly and if they want can mimic what they think the characters act and sound like. 5. After this is done, the teacher will ask the reporters what they found out. The reporters will show what they asked and what they heard (it helps to write some of the responses on the board). 6. When the responses are on the board, the teacher will lead the class through a discussion about the answers. The teachers should ask questions like why a character feels the way they do, whether or not characters feel justice was exacted, what the characters will do next now that the sentences have been dished out, and whether or not the students feel that what happened was what should have happened. Adapted from Teaching Shakespeare into the Twenty-First Century. 16 Hughes Tipping Off Bassanio Description and Reasoning: One aspect that becomes difficult to teach to students is the idea that a director can choose how to present lines. Reading the lines from a play is one thing, but performing them can be completely different. An actor can deliver the a line as it is written or he or she can emphasize certain syllables, pause in the middle of a line, or gesture during delivery to add meaning to the words. Through this activity students will: Understand the choices a director may or may not make Read into lines with a different perspective Question how an actor may deliver a line Materials: Three boxes with differing characteristics, such as size, color, or a form of decoration. Three “prizes”. One prize needs to be a reward and the others should be booby rewards. A copy of The Merchant of Venice for reference. Procedure: 1. Choose a “Bassanio” and send him/her out of the room 2. Arrange the three boxes at the front of the room. Make sure that there are distinct differences between them so the participants can pick correctly. 3. Put the three “prizes” in the boxes. 4. Let “Bassanio” back in and choose a “Portia” and have him/her help “Bassanio” choose the correct box. The advice has to be indirect and can be in the form of conversation or song. There can be no emphasis such as pausing, exclaiming a syllable, or gesturing at a box. The hints have to be subtle. If a “Portia” is too specific, the class can disqualify him/her. 5. Give “Bassanio” an extra minute to make up his mind. Once he chooses, unveil the “prize” and give it to him/her. 6. Repeat a few times with new students to give out more prizes and drive home the point. 7. Discuss. Ask questions like: How would this work in an actual performance? Do you think the actor playing Portia should do this? Why or why not? Does it improve the play? If Portia does decide to give hints, how does this characterize the two lovers? How do you think Bassanio would react to this on stage? Do you think this fits in the play given the relationship that Bassanio and Portia share? Adapted from ShakesFear and How to Cure It. 17 Hughes Annotated Bibliography Bradbrook, Muriel. Muriel Bradbrook on Shakespeare. New Jersey: Barnes and Noble Books, 1984. Print. This is another basic resource that provides some insight into the more complex themes present in Shakespeare’s plays. It presents some themes that are specific to certain plays, but it also has some more general ideas like disguise that can be applied to many plays. I think this resource would be great in helping to give ideas for discussion topics and to answer any questions that teacher may not know. Belsey, Catherine. Why Shakespeare?. New York: Palgrove Macmillan, 2007. Print. The book lists many reasons for reading Shakespeare, such as his use of language, the survivability of his plays, the fact that the stories ring true today and are familiar, and his enchanting quality of writing. The book then goes further and begins evaluating specific plays and the importance that each play has in drama. This is a very good book for helping to understand the importance of specific plays and it also helps crack some of the code that these plays present. Cohen, Ralph Alan. ShakesFear and How to Cure It: A Handbook for Teaching Shakespeare. Clayton, Delaware: Prestwick House, 2006. Print. I really enjoyed this resource. It divides up the lessons that it offers based on what the teacher wants to teach or by the play the teacher is teaching. It is very well organized and I navigated it very easily. It’s a resource that can be turned back to in case a teacher doesn’t know where to go with a play. It addresses the many issues that come along with Shakespeare and it does effectively remedy these problems. Folger Shakespeare Library. Washington, D.C.: Folger Shakespeare Library, 2013. Web. 6 Nov. 2013. This is a fantastic resource for finding lesson plans and for finding other resources to help teach Shakespeare. It has books that can be bought for specific plays and used to help simplify ideas for students. It also has a blogging site that I found particularly useful because it has videos from other teachers discussing what they do to introduce and teach Shakespeare to a variety of grade levels. There is almost an infinite amount of resources for teachers on this site. Greenblatt, Stephen. Shakespeare’s Freedom. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago, 2010. Print. This is great resource for accessing the themes in the plays of Shakespeare, especially The Merchant of Venice. One of the chapters discusses the ideas of hatred that flow in The Merchant of Venice. It discusses where these hatreds come from and why they exist. One thing that I found particularly clever and eye-opening was how the author modernized the hatred of the Jews in the play to the hatred that can be experienced today towards Muslims. I think it does a good job of keeping the themes of some of the plays modern and relevant, which is very important when trying to connect Shakespeare to students. Halliday, F.E. The Enjoyment of Shakespeare. 1952. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1973. Print. 18 Hughes I think this book helps to remind teachers that reading and instructing Shakespeare strictly to instruct Shakespeare is a terrible approach. It reminds teachers that the goal of a Shakespeare lesson is to help students understand Shakespeare so that they can enjoy it and see how fun it actually is to read Shakespeare. The book goes into subjects such as addressing the prose and verse in Shakespeare’s plays and helps to educate the difference between them, but it also delves into the life of Shakespeare and how we came about acquiring his plays. It presents these subjects to interest readers about how lucky we are as a society to have his plays. Hapgood, Norman. Why Janet Should Read Shakspere. New York: The Century Co., 1929. Print. I think this book can be really helpful in helping to inspire the teacher to want to teach Shakespeare if he or she has lost touch with his or her lesson plans. It also helps to focus the curriculum a little bit. There is an entire chapter devoted to helping to educate about the female representation in Shakespeare. If for example I had to teach Measure for Measure, I could look to this book for a better understanding of Isabella and then use this understanding to bolster a lesson plan. Lelyveld, Toby. Shylock on the Stage. Cleveland, Ohio: Western Reserve University, 1960. Print. Obviously, this book is tailor made to be read by a teacher teaching The Merchant of Venice. It is a very useful book in establishing the character of Shylock and showing students how the times have influenced the portrayal of the character, despite the character being the same within the play itself. This book can help to really break down the character of Shylock and can help to build sort of an expertise on Shylock and the actors that have played him. Noble, Adrian. How to do Shakespeare. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print. This book is meant for actors and directors to read so that they can put on an outstanding performance of Shakespeare, but it is also invaluable for teachers. It gives a unique perspective into the performance aspect of Shakespeare and allows the teacher to help educate his or her students on what it takes to put on something as daunting as Shakespeare. It includes how to access his language, meter, prose, and the journey through the play. Paris, James F., and Ronald E. Salomone, eds. Teaching Shakespeare into the Twenty-First Century. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1997. Print. This source has lot of great ideas on how to involve the class in learning about Shakespeare. It has activities that serve as a warm-up to learning about specific Shakespeare plays. The activities are simple enough that they can be used for grade school students, but not childish enough that high school students aren’t above doing them. It also addresses the many problems that students will have, such as language and content. It’s perfect for building lesson plans. Price, George R. Reading Shakespeare’s Plays. Great Neck, New York: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., 1962. Print. This is a great resource for students to help decipher and push through Shakespeare’s works, but it can be read from the teaching perspective to see what problems his or her student 19 Hughes will face. A teacher can read through and evaluate his or her lesson plans to see if he or she is addressing any problems that the book discusses in these lesson plans.