Contemporary & Traditional essay writing

advertisement

Year 12 Studio

Contemporary Vs Traditional.

Research the examples given of both traditional and contemporary aboriginal

artworks bellow.

Answer the following questions filling in information from your research.

Essay

Traditional

Rainbow Snake

1959

Crane and Fresh

Water Shrimp

1909

The Mythic Kangaroo

1950 (by Gonwinggo)

Contemporary

Bennet Nickols

(more examples in these notes)

(SELECTED ARTFORM IS PAINTING)

Comparison Between Traditional and Contemporary Aboriginal Artist

The points of comparison are listed below.

You are to identify in depth any similarities and differences.

(EACH DOT POINT SHOULD REPRESENT 1 OR 2 PARAGRAPHS IN THE ESSAY)

Individual Style

Were the early traditional artists individual in their painting styles ?

Example: Contemporary guys are obviously different and unique

Cultural Influence

How the times in which the works were created actually influence the work?

Dreamtime vs. Discrimination

Obvious difference in one is – identifying with their environment and embracing

culture Dreamtime.

The other is at odds with the culture contemporary (loss of identity/out of place)

Techniques and Materials

What is different/similar about how they approach painting?

Similar: Dot rendering, acrylic and water based ochres

Different: Brushes, subject matter, canvas vs. bark

(How have new materials changed techniques?)

Work Environments

Caves (open air) vs. studio

How does the physical work environment affect the work?

Artistic Influence

Have other artists influenced current day artists?

Who/Where do they get ideas/inspiration from?

Technology

Have new technologies influenced painting (Similar to Technique)

THE DREAMTIME

According to Aboriginal belief, all life as it is today - Human, Animal, Bird and Fish is part of one vast unchanging

network of relationships which can be traced to the great spirit ancestors of the Dreamtime.

The Dreamtime continues as the "Dreaming" in the spiritual lives of aboriginal people today. The events of the ancient

era of creation are enacted in ceremonies and danced in mime form. Song chant incessantly to the accompaniment of

the didgeridoo or clap sticks relates the story of events of those early times and brings to the power of the dreaming to

bear of life today.

THE SACRED WORLD

The Dreamtime is the Aboriginal understanding of the

world, of it's creation, and it's great stories. The

Dreamtime is the beginning of knowledge, from which

came the laws of existence. For survival these laws must

be observed.

The Dreaming world was the old time of the Ancestor

Beings. They emerged from the earth at the time of the

creation. Time began in the world the moment these

supernatural beings were "born out of their own Eternity".

The Earth was a flat surface, in darkness. A dead, silent

world. Unknown forms of life were asleep, below the

surface of the land. Then the supernatural Ancestor Beings

broke through the crust of the earth form below , with

tumultuous force.

The sun rose out of the ground. The land received light for

the first time.

Dreamtime painting by Norbett Lynch

The supernatural Beings, or Totemic Ancestors, resembled creatures or plants, and were half human. They moved

across the barren surface of the world. They travelled hunted and fought, and changed the form of the land. In their

journeys, they created the landscape, the mountains, the rivers, the trees, waterholes, plains and sandhills. They made

the people themselves, who are descendants of the Dreamtime ancestors. They made the Ant, Grasshopper, Emu,

Eagle, Crow, Parrot, Wallaby, Kangaroo, Lizard, Snake, and all food plants. They made the natural elements : Water,

Air, Fire. They made all the celestial bodies : the Sun, the Moon and the Stars. Then, wearied from all their activity, the

mythical creatures sank back into the earth and returned to their state of sleep.

Sometimes their spirits turned into rocks or trees or a part of the landscape. These became sacred places, to be seen

only by initiated men. These sites had special qualities.

PHYSICAL WORLD

" OUR LAND OUR LIFE "

'We don't own the land, the land owns us'

'The Land is my mother, my mother is the land'

'Land is the starting point to where it all began. It is

like picking up a piece of dirt and saying this is

where I started and this is where I will go'

'The land is our food, our culture, our spirit and

identity'

'We don't have boundaries like fences, as farmers

do. We have spiritual connections'

Land means many things to many people. To a farmer, land is a means of production and the source of a way of life. It

is economic sustainability. To a property developer, it is a bargaining chip and the means of financial progress and

success. To many Australians, land is something they can own if they work hard enough and save enough money to buy

it. To Indigenous people land is not just something that they can own or trade. Land has a spiritual value.

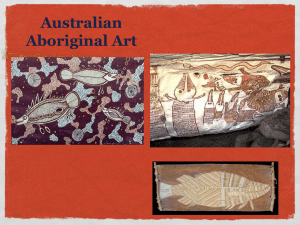

TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL ART

AN INTRODUCTION

Though comparable patterns and designs were once created elsewhere in Australia, the surviving style of ground

mosaics appears to have been restricted to the people of the Centre - to the majority (but not all) of those living in the

major range country, north from Alice Springs for about eight hundred kilometres and west to south-west to the

Western Desert country.

European settlement and the spread of Christianity very largely destroyed the ceremonial life of our Arrernte group plus

Pitjantjatjara, Pitubi, Walpiri, Amnatjira and Warramunga tribes.

Ground mosaics are the most elaborate of our art works, but complementary designs and decorations are applied to the

bodies and specially constructed head dresses of actors: to secret-sacred ritual objects that are stored near the

ceremonial grounds; and often to shields, boomerangs and other weapons.

MYTHOLOLGICAL FORCES

The design elements are not, in themselves, considered dangerous. But in a ceremonial situation, when the correct

secret-sacred chants are sung, they are believed to partake of mythological forces, whose essence they pass on to

otherwise profane objects. Thus, the dancers and the objects they use are thought to become imbued with supernatural

power. If not made unrecognisable in rituals, the decorations are usually destroyed immediately afterwards, for most

are not to be displayed in secular situations.

The mythological beings, to which all Aboriginal people are totemically and ancestrally related in one way of another,

are regarded not as really dead so much as at watchful rest. They still live in rock-holes, caves, clay-pans and other

natural features. Sacrilegious behaviour, or casual regard for ancient custom and law, may so anger the supernatural

beings that death and destruction follow. Sacrilege tat is recognised on the instant must be punished on the instant, so

as to placate the creative ancestors.

GROUND PAINTINGS

The artists creating the ground paintings are all men; inevitably, they are well into middle age, for only after extensive

and often very painful ritual is one knowledge and competent enough to depict the designs correctly. Younger but still

ritually correct men are sometimes employed as assistants (obviously, a period of introductory instruction is required),

but few men involved in making ground mosaics are under forty. Women have similar styles of body markings, have

limited numbers of sacred objects and dances, and may mark the sand with leaves, sticks or their hands in the telling of

stories; but they are not involved in making the decorated ground paintings.

No one man can create a ground design. In the complexity of Aboriginal social situation, each site that is still 'living' has

at least two men who stand in a 'keeper-owner' relationship to it and two men called Kutungulu ('inspectors' or

'policemen') who ensure that their keeper-owners maintain correct protocol. Similarly, unless given formal dispensation,

men can create only those paintings over which they are recognised as having authority: there is no concept of total

artistic freedom in the Western sense.

40,000 YEARS TO DESIGN

Each major secret-sacred ground painting represents both an individual identifiable geographical locality and a

mythological incident that occured there, although is inevitable that related sites and incidents will also be recalled. As

there are hundreds upon hundreds of differents sites in a tribal territory, ranging from individual tress or rocks to

mountains, the most learned old men may well know the details of hundreds of paintings - even possibly, of more than

a thousand. The designs must be relatively static in composition and have persisted over a great meny generations to

allow for such feats of memory.

ROCK ENGRAVING

An indication of the ancient derivations of the ground art is that identical designs elements occur in the rock engravings,

some of which are now known to be about twenty thousand years old. Plain and concentric cirlces, straight bar-lines and

sinuous lines and animal tracks prevail in each art form. The major difference is probably, the regular inclusion of arcs

(representing seated figures) in ground painting. There a similarity is the absence of the square or rectangle, a design

element that frequently occurs on woomeras (spear throwers), hard-wood shields and other wooden objects. Despite

the similarities, however, the fragile nature and purposeful destruction of ground paintings - presumably in ancient

times as in modern - makes it unlikely that we will ever know when this form of art became prevalent.

EWANINGA

All ground paintings, and the modern paintings on canvas or art-board which are derived from them, are meant to be

seen as plan views. This is almost certainly influenced by the hunting and foraging life-styles that the Aborigines once

followed and, to varying degrees, still do. It is a great asset, when travelling the bush, if the slightest sign of a track - a

scratch on clay or recognised as indicating the time and direction of travel, and the type of animal that caused it.

Conservation of energy in the hunt is almost as essential as the discovery of game. (The exceptional tracking skills of

the Aborigines have been successfully used for finding lost people or seeking out criminals; Aboriginal trackers are

employed by the police in all remote areas.)

ACRYLIC PAINTINGS

Acrylic paintings are merely a new form incorporating the classic elements of Aboriginal Life. They state a person's

relationship to those around them, to the land and to the Dreaming. They also represent a new context of interaction

between indigenous and western societies. Through modern art the Aboriginal people are able to introduce and express

their culture to the world.

CONTEMPORARY ART

Acrylic paintings by Central Australian Aboriginal people is one of the most exciting developments in modern Australian

Art. The paintings are mythical representations of landscapes or conceptual maps of designs wrought by ancestors. In

this tradition, paintings, dances and songs relating to the Dreamtime are repeating the work of Ancestors, thus keeping

the Dreaming alive.

HISTORY

It was the arrival at Papunya in 1971 of a young school teacher, Geoff Bardon, that provided the catalyst for an

explosion of the modern form of artistic expression. Acrylic on canvas.. Bardon started a school project to paint a mural.

The painting was taken over by elders who used traditional art to create "Honey Ant Dreaming", the Dreaming for

Papunya 300 km west of Alice Springs.