Courts Neg Wave 3 - Open Evidence Archive

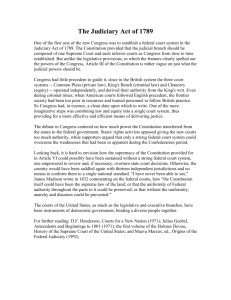

advertisement