Cultural PsychologyDM.

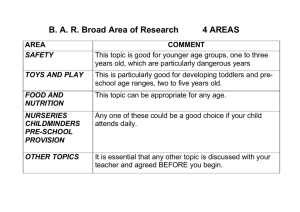

advertisement

Cultural Psychology Daniel S. Messinger, Ph.D. Cultural Psychology All social and emotional development occurs in a cultural context Culture involves shared beliefs and practices which unite communities and differentiate them from other communities What may appear to be a universal feature of development, is often one of myriad, cultural solutions to a problem Examples What to do when baby cries Where should baby sleep Who should play with baby Who should take care of baby What about rambunctious toddlers Background Social smile first sign of socio-emotional development Emerges around second month of life Maternal emotional behavior acts as a mechanism Differs based on culture Independent Interdependent Results Discussion Overall, there are culturally differential developmental pathways of social smiles Do you think there are other mechanisms that affect social smile? Do you think this data would look different if comparing low SES mother-infant pairs to high SES mother-infant pairs Physical contact Hispanic mothers report touching more frequently, being more affectionate with their infants and having more skin-to-skin contact. Observations: no overall differences in motherinfant touch, but Hispanic mothers showed more close touch and more close and affectionate touch compared to Anglo mothers, who showed more distal touch. Infants were 9 months old Franco F, Fogel A, Messinger DS, Frazier CA. Cultural Differences in Physical Contact Between Hispanic and Anglo Mother-Infant Dyads Living in the United States. Early Development and Parenting 1996;5(3):119 - 127. What about Miami? Does parental touch differ between Hispanics and non-Hispanics? What functions might differences serve? Autism Age of diagnosis Assortative mating (Tronick et al. 1987) Efe People Ituri forest of Zaire Small communities of a few families Leaf huts face a communal space High mortality rates, low fertility High work load; most gathering is communal Multiple caregivers, infants engaged with others half the time Methods Naturalistic, one community at both points Data gathered at different times Researchers living in these camps Some variation in when the observations were made Mattson Multiple, simultaneous relationships ‘The Efe infant experiences a pattern of simultaneous and multiple relationships. Not a pattern initially focused on one person that gradually progresses to other relationships. This simultaneous pattern is influenced by physical and social ecological factors and cultural practices. This pattern of social experience leads to a sense of self that incorporates other people Tronick, E. Z., Morelli, G. A., & Ivey, P. K. (1992). simultaneous. Developmental Psychology, 28(4), 568-577. The Efe forager infant and toddler's pattern of social relationships: Multiple and Privileged Treatment of Toddlers: Cultural Aspects of Individual Choice and Responsibility. Christine Mosier and Barbara Rogoff The study: 16 Mayan families from San Pedro, Guatemala 16 middle class families from Salt Lake City, Utah Interactions between toddlers (14 to 20 mo) and siblings (3 to 5 yrs) Interview with mother about child-rearing, social behavior, etc. Given 9 objects to toddlers and siblings to manipulate, with mother’s help Nayfeld Guatemalan Mayan mothers “almost never overruled their toddlers' objections to or insistence on an activity—they attempted to persuade but did not force the child to cooperate toddlers were not compelled to stop hitting others. [Toddler] hitting was not regarded as motivated by an intent to harm because they were expected to be too young to understand the consequences of their acts for other people.” Mosier & Rogoff, 2003 Proportions of Events Regarding Access to an Object Event Salt Lake City .59 (.20) San Pedro .87 (.09) Mothers endorsed toddler’s privileged position .43 (.24) .63 (.22) Mothers endorsed toddler’s nonprivileged position .25 (.13) .04 (.05) Siblings endorsed toddler’s privileged position .45 (.19) .80 (.09) Siblings endorsed toddler’s nonprivileged position .54 (.21) .19 (.09) Toddlers eventually gained access to the object Nayfeld Maternal education (acculturation) San Pedro mothers’ schooling related negatively to their privileged endorsements (r .50, p < .05) and uninvolvement (r .57, p < .05) and related positively to their nonprivileged endorsements (r .56, p < .05). Affects siblings Salt Lake City: The older brother (3 years 0 months) was playing with the pencil box and lid. Sam (15 months) wanted the lid and grabbed for it. A tug-of-war ensued until both mother and father separated the two boys. The older brother ended up with the complete box and Sam ended up playing with the embroidery hoop. San Pedro: The older brother (3 years 9 months) put his hand on the knob of the jar lid. Lidia (15 months) reached out and gently pushed his hand off. The brother removed his hand. Reverse dominance hierarchies? A hefty 15-month-old… walked around bonking his brothers and sisters, his mother, and his aunt with the stick puppet that I had brought along. The adults and older children just tried to protect themselves and the little children near them, they did not try to stop him. When I asked local people what this toddler had been doing, they commented, “He was amusing people; he was having a good time.” Was he trying to hurt anybody? “Oh no. He couldn't have been trying to hurt anybody; he's just a baby. He wasn't being aggressive, he's too young; he doesn't understand. Babies don't [misbehave] on purpose.” (p. 165) Attention to Interactions Directed to Others: Cultural variation in children’s attentiveness Guatemalan Mayan & European American Pueblo basic vs. Mexican high school Indigenous vs. westernized learning styles Maternal education level and cultural traditions Toy construction paradigm Correa-Chavez & Rogoff, 2009 Bustamante Kids’ Attention to Interactions Directed to Others Bustamante Interdependence vs. autonomy? American children are socialized to be relatively autonomous, while Japanese children are socialized to work interdependently in groups (Benedict, 1974; Conroy et ah, 1980). Japanese mothers more frequently focus their infants' attention within the mother-infant dyad, while American infants spend more time engaged with toys and vocalize or initiate vocalizations more frequently (Bornstein et al., 1985-1986; Caudiil and Weinstein, 1969; Shand and Kosawa, 1985) Cultural Differences in Child’s Play (Cote & Bornstein, 2009) European American children – engage more exploratory or object-related play Argentina and Japan children – engage in more symbolic, person-directed play Why? Celimli Findings (Cote & Bornstein, 2009) Children’s play tends to be more sophisticated when their mothers encourage them than when children initiate play or play alone No cultural differences here Japan “being voluntarily cooperative, sunao, is encouraged: A child who is sunao has not yielded his or her personal autonomy for the sake of cooperation; cooperation does not suggest giving up the self as it may in the West; it implies that working with others is the appropriate way of expressing and enhancing the self. … How one achieves a sunao child … seems to be never go against the child.” Turtle task. 24- to 31-month-olds Japanese mothers more frequently assisted their toddlers in fitting a shape before the toddlers had tried to fit the shape on their own (interdependence); American toddlers did not attempt to fit more shapes on their own (autonomy); More American toddlers left the task than did Japanese toddlers (autonomy). Figure Video: Turtle task Apparent developmental discontinuity While the desires of Japanese infants are indulged, school-age children are expected to regulate their desires to conform to the demands of working in a group (Hendry, 1986). A sharp contrast is thought to exist between the infant-centered relationship with the mother in the home and the expectation that 3-year-olds, upon entrance to nursery school, will learn to conform to shudan seikatsu, 'life in a group' (Peak, 1989) Japanese discontinuity In traditional practices that may seem indulgent to Western eyes, Japanese mothers do not go against the young child's will but use other ways to foster self-motivated cooperation Traditional Japanese belief holds that it is not appropriate to control young children from the outside, because use of controlling behavior (such as anger or impatience) leads children after age 10 or 11 to resent and disobey authority rather than to cooperate with others Differential attributions Children are never willfully bad What are the results of such a belief? Behavioral Inhibition in Chinese Children Behavioral Inhibition (BI) tendency to exhibit vigilance, anxiety, and wariness in response to unfamiliar or challenging situations stable temperamental factor that affects up to 15% of typically developing children (Fox et al., 2005) Developmental outcomes of BI in North America in Western cultures, has been associated with socioemotional and school difficulties, social anxiety, and depression Behavioral Inhibition in Chinese Children (cont) Mechanisms leading to negative outcomes? Caregiver attitudes (e.g., rejection, disapproval) Responses of caregivers, teachers Lack of peer acceptance Negative self-perceptions Cross-cultural similarities in behavioral patterns But does BI have same significance in different cultural contexts? Age 2 inhibition predicts age 7 outcome Predictive Associations Behavioral Inhibition in Chinese Children BI has also been linked to higher morning cortisol, higher startle response, and elevated morning cortisol (Degnan, Alams, & Fox, 2010). Are these physiological differences a function of BI or of parental/environmental/cultural responses to BI? How generalizable do you think the findings are… At other times (vs. 1994-1999)? To other regions? Culture and Peer Interactions (Chen, 2012 How is culture transmitted to a developing child? Emphasis on social mediation Culture Peer Interactions Social Development Culture and Peer Interactions (Chen, 2012) Chen, Wang, & DeSouza, 2006 But… cultures change Yang, F., Chen, X., & Wang, L. (2015). Shyness-Sensitivity and Social, School, and Psychological Adjustment in Urban Chinese Children: A FourWave Longitudinal Study. Child Development, n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12414 Culture and Peer Interactions (Chen, 2012) What are some unique aspects of culture transmitted via peer interactions vs. other types of socialization experiences? Parenting Style and Child Adjustment Previous findings suggest ethnic differences within North American sample in relations among harsh parenting and child adjustment? Proposed mechanism accounting for differences? Rohner’s (1986) parental acceptance-rejection theory Grusec and Goodnow’s Framework What is missing- how culture might affect the way children make these judgments Fig 1; Lansford et al., 2005 Autonomy vs. Interdependence? Value system, rules, and the structure of the family unit have been formed through the societal demands which show variances across time and cultures. A model of family change (Kağıtçıbaşı, 1996a, 1996b) - analyzes the link between the self, family, and society in order to explain cultural differences Celimli Family Interaction Patterns (Kagitcibasi, 1996, 2005) total interdependence: dependence: The child is the economic value Independence of the child is not valued or evaluated Obedience is fundamental to childrearing The child: a source of economic costs Independence of the child: highly valued Autonomy is the basic childrearing orientation psychological interdependence: The child: no longer the economic value Psychological interdependence of the child: valued Closeness and relatedness (not separateness) is the ultimate goal in childrearing practices Celimli Parenting Style and Child Adjustment (cont) Mothers’ self-reports of own use of physical discipline- similar patterns found for perceptions of normativeness by mothers and children- differed between countries Figure 2, Lansford et al. Does normativeness moderate association between physical discipline and adjustment? By country “In the anthropology literature, there are many examples of parental behaviors that appear to have no detrimental effects on children’s adjustment, despite the perception in other cultural contexts that these behaviors would be harmful to children.” (p. 1242) How to study Should we take a (likely Western) construct and apply it across cultures E.g.:Italian mothers were more sensitive and optimally structuring, and Italian children were more responsive and involving, than Argentine and U.S. dyads.’ (Bornstein et al. 2008) Or should we adopt constructs from the cultures we are studying? E.g. Rogoff What about subcultures here in Miami?