Theory of Income and Employment Determination

advertisement

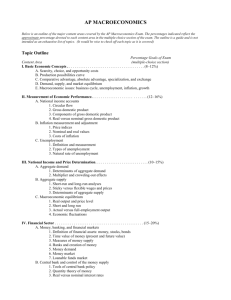

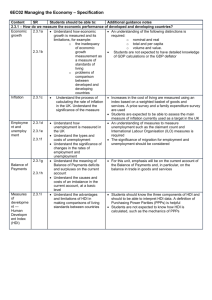

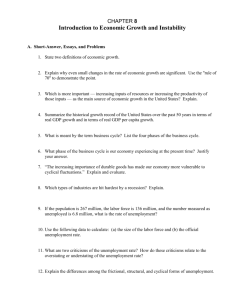

Theory of Income and Employment Determination Background: 1. Up to the 1930s. Say’s Law: “Supply creates its own demand”. The process of production creates simultaneously creates the product and the income to purchase it. Short term imbalances may lead to temporary unemployment or inflation, but markets adjust to restore equilibrium, eliminating excess supply or demand. Imbalance in savings and investment will be resolved by shifts in the interest rate. 2. Keynesian Economics. Economy is led by demand. Long-term unemployment is created when Aggregate Demand is at equilibrium below the level to generate full employment, this is demand deficient unemployment. Wages are sticky downwards, so labour markets do not automatically adjust. Savings and Investments are resolved by changes in National Income rather than Interest Rates. 3. Milton Friedonomics. Supply-side policy, stagflation (high inflation and high unemployment despite Fiscal and Monetary Policy) due to structural unemployment. Focus on increasing market flexibility by lowering tax rates, reducing the power of unions, privatizing as much of the public sector, lowering unemployment benefits, making wages flexible and providing the infrastructure to support private enterprise. Aggregate Expenditure/Income Approach: key assumptions: fixed price level, fixed rate of interest AE = C + I + G + (X – M) Where C = Consumption I = Investment (both capital and inventory investment) G = Govt Expenditure X = Exports M = Imports Consumption/Savings: Act of using Income for the purchase of consumption goods. Savings (S) is anything not spent. Average Propensity to Consume (APC). The proportion of total income spent, and can be calculated by APC = C/Y Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC). The change in C for any given change in Y and can be calculated by MPC = change in C/change in Y. Consumption Function: C = A + bY. Where A is autonomous consumption and b is the MPC. Graphical: when C>Y, dissaving when C = Y, saving is zero when C < Y, savings are positive. Savings (S) = Y - C Determinants of Shifts in the Consumption Function: Note: a movement along the consumption function can only be caused by a change in income. 1. Wealth. Pigou Effect. If wealth rises then C will rise, and if wealth falls C will fall too even if Y remains the same. E.g. Stock Markets or Property Markets falling or crashing. People’s real wealth also falls with inflation. 2. Expectations: Optimism about future economic growth means C will rise, whereas pessimism regarding the future means C will fall. Expectations about future inflation are also important, if prices are expected to rise, C will increase. They tend to be self-fulfilling (e.g. demand increasing for a particular good drives up the price). 3. Interest Rates: Affects consumer durables and other goods that require borrowing. At higher interest rates C is likely to fall. However, this is not symmetrical as at lower rates, it may not necessarily rise. 4. Distribution of Income: If the rich have a lower MPC than the poor then a redistribution of Y from rich to poor will cause C to rise for a given level of NY (and vice versa). 5. Tastes and Attitudes: Some countries are more frugal than others. Gross savings as % of GDP: Singapore 46%, S.Korea 32%, Japan 22%, USA 12%, UK 11%, Greece 10%. Attitudes can change over time. 6. Durable Goods: 1) Echo cycle as worn out durables are replaced. 2) After a recession everyone replaces the durable goods they are holding on to. 7. Taxation: Increase/Decrease in Taxation will cause a similar shift of the consumption function down/up. If C is plotted against disposable Y, taxation will cause a movement along the consumption function. DWITTED. Alternative Views of the Consumption Function (useful for evaluation/end of essay): Permanent Income Hypothesis(Friedman): People look at their incomes over a long period and adjust their spending based on what they feel they will earn in the long term. This reduces the impact of short-term boosts to income (like tax cuts) on consumption. See: Barro-Ricardian Equivalence. Lifecycle Hypothesis (Modigliani): Expenditure varies according to what stage of life you’ve reached. Households adjust spending according to that more than current income. Also implies that short term changes in Y will have little impact on C Investment: Investment is expenditure on new plant and capital equipment (including housing) and changes in stocks (inventory) Generally I is very volatile, especially inventory investment, and changes in I have a big impact on instability in the economy. It is very important to remember that Investment affects AD in the short run but AS in the long run. Determinants of Investment: 1. Rate of Interest: Classical Theory holds that I is inversely related to the i/r through the Marginal Efficiency of Investment (MEI). However, Keynes felt that the MEI was both inelastic and unstable. Hence i/r may not be that important. 2. Business Confidence/Expectations: Keynes’ famous Animal Spirits. Businessmen will invest regardless of how high the i/r is if they are confident, whereas a low i/r may not make them invest because of low confidence. Current state of the economy, political factors, global situation and gut instinct. 3. Cost and Availability of Capital Goods: New technology or breakthroughs in technology can affect I. Innovation stimulates I and there can be an echo cycle when one round of new technology ages. 4. Rate of Change of Income: Accelerator Effect. An increase in sales can cause a more than proportional increase in I, it responds to the rate of increase in NY. Assumption: I is exogenous. The Paradox of Thrift: Fallacy of Aggregation As the great depression formed, people chose to save a larger proportion of their income; however the drop in interest rate did not cause investment to increase. Instead, the rise in the savings function had in fact caused a fall in the equilibrium level of income, hence although a larger proportion if income was saved, real income had fallen. This has the effect of worsening or deepening a recession. The Multiplier: The multiplier is the amount NY will increase for a given increase in J assuming price levels and interest rates remain fixed. In an open economy, the multiplier can be looked at as 1/[MPW], where MPW = MPT + MPImp + MPS Due to the circular flow of income, one injection in the form of Government Spending or Investment in one area can cause a ripple effect where injections create jobs, that creates more income that can be spent on other things, which results in more employment so on and so forth. Magnitude of increase depends on the rate of leakages in the economy. Income-Expenditure Graph 1) At Y2 : AE < Output, There will be an unplanned build up of stocks, (unplanned inventory investment, realized I will exceed planned I). Consequently firms will reduce production in the next time period and NY will fall 2) At Y1 : AE > Output. There will be an unplanned running down of stocks (unplanned inventory disinvestment, realized I will fall short of planned I). Firms will increase production in the next time period and NY will rise. 3) At Ye: AE = Output. There will be no unplanned changes in stocks, Firms will continue to produce the same level of output, and the economy is in equilibrium. Withdrawal-Injections Graph The above applies for the W-J graph as well, but it can be explained by how S > I, hence leading to an unplanned build up of stocks etc, instead of Income and Expenditure. Circular Flow of Income: Equilibrium and Full Employment: 1. Deflationary Gap the amount by which AE falls short to secure full employment Unemployment caused by a lack of demand (demand-deficient unemployment). The deflationary gap demonstrates the amount AE needs to be boosted in order to secure full employment 2. Inflationary Gap The amount by which AE exceeds that necessary to ensure full employment. Equilibrium in the economy is beyond the level of full employment, so there will be inflation in the economy caused by an excess of demand (known as demand pull inflation). Both models assume that the AS curve is right angled. Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply AD: “the total level of spending in the economy”, it is like AE but the price level is part of the model and is in itself an influence on AD. It is inversely proportionate to price because of: 1) The Income Effect. At higher prices the real value of wages falls, so households will not be able to afford to spend as much. 2) Substitution Effect: which has three elements a. At higher prices foreigners are less inclined to buy our exports and we are more inclined to buy, so (X-M) falls. b. The wealth effect- real balance effect – at higher prices the value of existing wealthis reduced so people save more (spend less) to top up their wealth c. Higher process often result in higher interest rates, which will choke off some spending by households and firms. AS: “the total amount of output in the economy”. The SRAS(short run aggregate supply) curve is drawn on the assumption that wage rates, other input prices, technology and the quantity of inputs available are all fixed. It is not perfectly elastic as: Variable factors become scarce as output expands, raising the costs of production. Therefore although firms want to increase output as the price level rises, they can only do so at a higher and higher cost to themselves.