Paper: Word file

advertisement

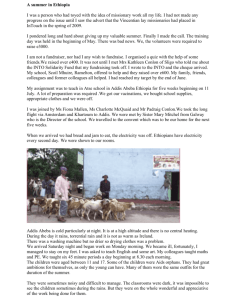

Charles Addis: Commercial Cosmopolitanism in the Thought of a Merchant Banker During the First World War Andrew Smith, University of Liverpool Management School a.d.smith@liverpool.ac.uk This paper examines the thinking of the British merchant banker Charles Addis through the lens provided by Transnational Capitalist Class (TCC) theory. Addis was a leading figure in the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), which was and is an important multinational. In the early twentieth century, he promoted the ethos I call commercial cosmopolitanism. In this paper, commercial cosmopolitanism denotes a mental framework in which national loyalties are subordinated to other abstract principles, such as a code of commercial honour, loyalty to business partners irrespective of nationality, and the teachings of classical liberalism. Addis articulated this ideology in his diary, private correspondence, and public statements. The world economy at the start of the twentieth century resembles the present in several crucial respects: it was characterized by extensive globalization (Rosenberg ed., 2012), high levels of financialization (Rajan and Zingales, 2003) and inequality (Piketty, 2014) and ongoing investment in communications and transport technologies that effectively reduced distance. The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 ended the first era of globalization and initiated several decades of de-globalization and definancialization (Ferguson, 2006; Findlay & O’Rourke, 2007; Frieden, 2006, 303; Mollan and Michie, 2012). According to one widespread interpretation, globalization did not resume until the post-1945 period, when the United States began to perform many of the functions that the previous liberal capitalist global hegemon, the British Empire, had discharged during its heyday (Kindleberger, 1986; Gilpin, 2011, 94-95). The historical research presented in this paper is significant for contemporary debates about the impact of globalization on the national allegiances of members of transnationalized business elite. In the early 1990s, a number of observers of international political business asserted that many MNEs were becoming borderless, transnational, and decoupled from any particular nation-states (e.g., Ohmae, 1990, 95; Reich, 1990). In this context, activists and social observers on both the left and the anti-globalization right of the political spectrum came to denounce corporate decision makers for their lack of patriotism (Nader, 2013; Stanley, 2012, 257). In the late 1990s, the moniker “Davos Man” has been applied to the elite individuals who gather at Davos, the annual transnational gathering that takes place in a Swiss resort (Beneria, 1999, 68; Robinson, 2012). Although some of the hyperglobalist reports of the death of nation-state power have clearly been exaggerated it is clear that a shift towards transnationality took place in the closing decades of the twentieth century and that this shift created an integrated global system that resembles that which existed on the eve of the First World War (Dicken, 2010, 7, 14, 83, 204). In more recent years, the business interests associated with globalized finance have been accused of disloyalty to their respective nation-states. For instance, in the aftermath of Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea, financiers in the City of London were criticized in the British press for their alleged opposition to the imposition of sanctions on Russian banks (Ruparel, 2014). Similarly, HSBC has recently been attacked in the United States for links to Mexican drug gangs and for helping Iranian banks (Barrett, 2015) to evade US sanctions (Morris, 2015). A recurring idea is that financial institutions are disloyal to the nation-states that charter them, and to the values of those nations. Similar accusations of the subordination of patriotism to profit were levied at Charles Addis and his employer during the First World War. Addis’s wartime experiences allow us to explore the politics of transnational class solidarity during a period of intense national rivalry. Transnational class solidarity is an important theme of the works on the First World War by historians interested in the working-class movements that had been part of the Second International before the war. Prior to 1914, trade unionists had spoken of the unity of the world’s workers, but once war broke out, this rhetoric disappeared: most German social democrats supported their country’s war efforts and most British and French trade unionists were equally patriotic (Winter, 2014). Far less has been published on the impact of the First World War on the bourgeoisie’s transnational loyalties. Like the European trade unionists and social democrats who were confronted in 1914 with the question of whether to support the war efforts of their respective nations, Charles Addis was torn between national and transnational class solidarities. We should, however, avoid pushing this analogy to far, as the bourgeois advocates of commercial cosmopolitanism such as Addis tended to come from the propertied classes in society and thus enjoyed a privileged position. bourgeois proponents of commercial liberalism were not prosecuted for their views. For instance, John Morley, the classical liberal politician who resigned from the British cabinet on 4 August 1914 to protest the country’s decision to declare war on Germany (Hamer, 1968, 368-9), was unmolested by the British government, perhaps because his opposition to the war was rooted in an oldfashioned Victorian belief in minimal taxation and non-intervention in foreign affairs. Addis, who shared Morley’s classical-liberal worldview but reluctantly supported the war effort (Addis to Mills, 9 August 1914), was even less likely to suffer because of his views notwithstanding his ongoing commercial interaction with German firms. In contrast, Britain’s socialist internationalists were criminally prosecuted during the war (Millman, 2014). In addition to being privileged due to his wealth, Addis enjoyed another advantage because he worked in the City (i.e., Britain’s financial service sector). As numerous scholars of political economy have argued the City has long enjoyed a privileged status in the British policy-making system that was not enjoyed by the manufacturing business interests that were geographically concentrated in northern England (Longstreth, 1979; Rubinstein, 1977, 116; Ingham, 1984; Morgan, 2012; Marshall, 2013). The City’s privileged connection to Whitehall help to explain why British financial institutions were allowed to continue trading with their German counterparts, albeit in a limited fashion, at a time when factory owners and small businessmen were being prosecuted under the Trading With the Enemy Act for engaging in commercial transactions for comparatively small amounts (see Table 1). The Transnational Capitalist Class On a theoretical level, this article is informed by the literature on the Transnational Capitalist Class (TCC) (Sklair, 1997; Sklair, 2012; Murray, 2014) and the role of ideology in helping the legitimate the activities of members of that class (Carroll, & Carson, 2003; Sklair and Gherardi, 2012). In writing about the TCC, it is important to recognize that the TCC overlaps only partially with the social category of the multinational firm. Some multinationals, particularly SOEs, defence and aerospace firms, and other “national champions,” are closely associated with a particular nation state (Liang, Ren, & Sun, 2014). The managers of such companies cannot be regarded as members of the TCC. In contrast, other TNCs are far more transnational or, more accurately, supranational. HSBC, which has used the slogan “the world’s local bank” since 1999, is in this category of multinational. HSBC, both in the present and in the early twentieth century, can be closely associated with the TCC. Writing in 1919, in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, Schumpeter (1919 [1951]) adapted class analysis to explain the interest-group politics that had contributed to the intensification of national animosities in the years before the outbreak of the war. Schumpeter identified the existence of two branches of the bourgeoisie. One element was cosmopolitan and largely pacific in its outlook. Schumpeter associated this element with the ideology of classical liberalism and with international trade. The other element of the bourgeoisie, according to Schumpeter, were the business interests associated with militarism, economic nationalism, and imperialism. Schumpeter was too sophisticated an observers to subscribe to the crude “merchants of death” interpretation of the origins of the First World War, but he nevertheless recognized that business interests had pulled policymakers in various directions in the period before the decision to go to war. Business historians have used archival research and thick description to show that business transnationality and rootlessness were actually common during the pre-1914 golden age of globalization. Speaking of the pre-1914 period, Geoffrey Jones (2013, 194) observes that “Ambiguous nationality was almost the norm rather than the exception in the extensive international business in services outside Western Europe and North America.” Geoffrey Jones cites a range of secondary sources that many firms had dynamic rather than static national identities. As Charles Jones has shown, the rapid growth in international trade that followed the Industrial Revolution and breakdown of the mercantilist colonial empires produced a class of cosmopolitan businessmen who felt comfortably operating in a variety of sovereign states. Jones (1987, 28) speaks of the creation of a “cosmopolitan trading community centred in London which nationality was often very blurred.” He remarks that this community’s “fundamental legitimising ideology was a secular one, economic liberalism: a profound faith in the collective virtue of aggregated individual self-interest and the moral validity of market sanctions.” He notes that this ideology was closely linked to Cobdenism, the radical variant of classical-liberal ideology that believed that free markets, reduced taxation, and global commerce would help to ensure world peace. Nineteenth-century commercial liberalism, he says, was cosmopolitan, individualistic, anti-statist, and anti-militaristic. Jones observes that “this community and its ideology” collapsed “in the years after 1890” as “firms and individuals” retreated into “the apron strings of newly assertive states. Nationalism and regulation, imperialism and racism, were the hallmarks of the fin de siècle.” The growing emphasis on the nationality of individuals and firms in the first decades of the twentieth century contributed to what has been called “the fall of the cosmopolitan bourgeoisie” (Jones, 1987). Jones argues that this period witnessed fragmentation of a preexisting transnational bourgeoisie into various national bourgeoisies. He argues that this fragmentation was driven by a range of factors, including a cultural shift in the direction of more intense nationalism in many countries. It is also clear that there was considerable resistance to the rise of economic nationalism. Normal Angell’s 1909 work Europe’s Optical Illusion, which stressed that economic irrationality of warfare in an era of international economic interdependence, became a best-seller and popular with many businessmen involved in international trade (Ceadel, 2011). Moreover, a large bloc of the British electorate continued to support the policy of Free Trade up until the First World War, notwithstanding the invocation of nationalist sentiment by protectionist business inteersts (Trentmann, 2009). Addis’s Banking Career and Place in the TCC Charles Stewart Addis was not born into the TCC. In fact, he came from a middle-class family that was very domestic in its orientation. He was born in Edinburgh in 1861. His father, who never appears to have left Scotland, was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, a Presbyterian denomination that had been founded in 1843 by Thomas Chalmers, a minister whose extensive and influential writings on political economy were informed by a strong variant of the ideology of laissez-faire and the invisible hand (Emmett, 2011; Kennedy, 2014). Although Chalmers did eventually endorse laws limiting child labour (Blaug, 1958), the main thrust of his writings suggested that market forces were created by God and that it was impudent for human governments to interfere with God’s will via protective tariffs or any other departure from laissez-faire. At Edinburgh’s High School, Addis was exposed to a range of religious, classical, and modern theories, including the ideas of Scottish Enlightenment. The historical meta-narrative promoted by Scottish Enlightenment thinkers such as Robertson, Hume, and Smith described a transition from tribal and feudal societies to cosmopolitan integrated commercial civilizations in which distant individuals were connected through a nexus of voluntary agreements (Höpfl, 1978; Herzog, 2013; Berry, 2013). Thomas Carlyle, a nineteenth-century thinker who attached the methodological individualism and classical liberalism of the Scottish Enlightenment, dismissively described modern commercial civilization as based on a cold, calculating “cash nexus.” Carlyle attacked the emerging social order on grounds that it deracinated individuals by diminishing the importance of the ties of locality and nationality (Levy, 2002). In 1880, the young Addis joined the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC)’s London branch. Thereafter, he was posted to HSBC branches in Asia, serving in Singapore, Hong Kong, Beijing, Tientsin, Shanghai, Calcutta, and Rangoon, and Hankow. These posts in Asia involved extensive interaction with businessmen of various nationalities, European, North American, and Asian. In 1905, Addis was transferred back to HSBC’s London Office. In 1911, Addis was promoted to the post of Senior Manager of HSBC’s London Office, a post he held until 1921. In 1921, Addis retired from the daily management of HSBC’s London branch, although he remained on its board and those of other important firms connected to the Far East. During the First World War, Addis acted as a government advisor. He was in Paris to advise the British delegation at the Versailles Peace Conference. In the 1920s and 1930s, Addis acted as a government advisor on a number of important topics, such as the future of India’s currency, the size of Britain’s national debt, commercial relations with Brazil, and whether Canada ought to establish a central bank modelled on the Bank of England. Addis also served on the General Council of the German Reichsbank, a body that had been established in promote investor confidence in Germany following the hyperinflation of 1923. In 1929, he was the British Delegate on the Committee of Experts for Reparations in Paris. In the early 1930s, Addis served on the commission that led to the creation of the Bank of Canada. In the late 1930s, as Addis withdrew from his remaining business and political commitments, he observed that while old-fashioned liberalism was now deeply unfashionable, he still adhered to his liberal beliefs. Addis died in 1945. (Dayer, 1988). Intellectual Context The Britain to which Addis returned in 1905 was far less committed to international Free Trade than it had been in 1880, when he signed up for overseas service in HSBC. In the 1880s, the mid-Victorian consensus in favour of international Free Trade and domestic laissez-faire was still largely intact. As Palen (2010) has shown, the highly protectionist tariff introduced by the United States in 1890 caused many Britons to question the economic orthodoxy of Free Trade, which had been British policy since the 1840s. The move away from laissez-faire and so-called economic “individualism” alarmed British classical liberals such as Herbert Spencer and A.V. Dicey (Taylor, 1992, 36; Perkin, 1977). Spencer (1884) denounced the “New Toryism” and the re-emergence of collectivist regulations similar to those that had been dismantled by classical liberals earlier in the nineteenth century. Classical liberalism was attacked by the “New Liberals” and by so-called “social imperialism”, which advocated an increasing number of departures from the policy of laissez-faire on the grounds that they were necessary to strengthen the British as an imperial race (Scally, 1975; Semmel, 1960). In the early twentieth century, social imperialist ideas influenced both of Britain’s main political parties, the Conservatives and the Liberals, (Cronin, 1991, 29-30, 37-8), as well as elements within the new Labour Party (Pugh, 2011, 71-77). Many Social Imperialists admired Germany, which under Bismarck’s leadership had introduced social programs and protective tariffs while also building up its military strength. For instance, Joseph Chamberlain, a Conservative who wanted Britain to revert to protective tariffs, admired Germany (Marsh, 1994). Even the young Winston Churchill, who left the Conservative Party to show his opposition to Chamberlain’s proposed return to protective tariffs, said that he wanted to introduce a “big slice of Bismarckism” into Britain, by which he meant both an activist welfare state and a more robust military (Himmelfarb, 2012, 258). Addis’s Defence of Commercial Cosmopolitanism Addis and Germany Addis’s belief in commercial cosmopolitanism was, in part, a function of his upbringing in mid-Victorian Scotland, but his ideas were also congruent with the needs of his employer, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC). HSBC was founded in the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong in 1865 and was thus legally a British firm. Nevertheless, individuals of a variety of nationalities were involved in the bank as shareholders, directors, and, at least in its early days, managers (King, 1988, 18-21, 171, 192-3, 537-9, 594-5, 625). The creators of the bank were “British, Parsee, American, German, and Jewish. Its first manager, who may have been French or German, was poached from the Comptoire d’Escompte,” a French bank with an extensive presence in British India and other Asian markets (C. Jones, 1987, 82). The highly internationalized nature of the bank reflected a broader pattern during the early phases of Western economic expansion into China. In this period, the actions of the Western states in China were frequently cooperative (Rowe, 2010, 236). For instance, the British authorities welcomed migrants of every European nationality into the Crown Colony of Hong Kong, at least until 1914 (Mak, 2004). The Colony soon acquired a large German mercantile community (Manchester Guardian, 18 April 1916). German and British businessmen lived together and cooperated in Shanghai’s International Settlement (Pott, 1928, 221) and in other Chinese ports. HSBC financed the operations of a number of German firms on the China Coast. These operations resulted in the establishment of a HSBC branch Hamburg. Four German firms were particularly important to HSBC: Arnhold, Karberg and Co., Carlowitz and Co., Melchers and Co., and Siemssen and Co. All four companies were represented on the HBSC’s board, which met in Hong Kong (King, 1988, 527). Despite deteriorating relations between Germany and Britain after 1905 (Kennedy, 1980), the bank’s four German directors did not resign their posts until war actually broke out on 4 August 1914 (South China Morning Post, 12 August 1914). HSBC’s ventures into public finance deepened its connection to German capital markets through the formation of syndicates that included German, as well as French and American, banks. HSBC worked closely with the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank (DAB), which was connected to Deutsche Bank, a major German universal bank (McLean, 1973). In 1912, Addis launched negotiations with banks in other countries to establish the Six Power China Consortium, which then issued a loan to support the new Republican government in China. The six nations whose banks were represented in this consortium were Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Japan, and the United States (Dayer, 2013). Charles Addis and Trading With the Enemy Following its declaration of war against Germany and Austria in August 1914, the British government was confronted with the question of whether it was going to permit commerce with Germany to continue. The British government had two contradictory sets of precedents it could follow. One model was suggested by the laws of the early modern period, when states had sought to ban virtually all commerce with the subjects of enemy kings during wartime. The other model was that of the Crimean War of the 1850s, the last major European war. In a move that reflected the ascendancy of classical liberal ideas and methodological individualism, which reached their high-water mark in midVictorian era, the British government opted not to interfere in private trade with Russia or with merchant vessels that belonged to Russian private citizens (Anderson, 1967, 254-272; Searle, 1998, 206-9). This war had been fought on the understanding that Britain’s grievance was with the Russian state, not individual Russian merchants (Levy and Barbieri, 2004). During the First World War, the British government’s approach to the issue of trading with the enemy was a somewhat confused mixture of the medieval and the classical-liberal approaches. It should be remembered that at the start of the First World War the motto of the British government was “business as usual” and that it was only towards the end of the conflict that Britain developed a full-fledged command economy with conscription and food rationing (Broadberry and Howlett, 2005). In other words, the ideology of economic liberalism continued to inform British economic policy during the early phases on the conflict. Shortly after the declaration of the war in August, the British government introduced a law that included a blanket ban on trading with enemy alien citizens and firms anywhere in Europe. A number of small businessmen resident in the UK were soon prosecuted for trading goods with German merchants via neutral countries. The goods mentioned in many of these indictments were of a non-military character, such as silk and lace (see United Kingdom Parliamentary Papers, 9 March 1915; Manchester Guardian, 22 February 1917). At the same time, many German citizens resident in the United Kingdom were interned and their property was entrusted to a custodian of enemy property (Panayi, 2014). Occasionally, anti-German sentiment led to crowd action against enemy alien property. For instance, after the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine in 1915, a mob in Liverpool destroyed German and Chinese businesses in a fit of xenophobic rage (Merseyside Maritime Museum, 2015). On the face of it, the Trading With the Enemy Act comprehensively banned dealing with Germans. However, pressure from the cotton merchants and other business groups with an interest in continuing trade with German companies led to the creation of numerous exceptions to the rule banning trading with the enemy (Lambert, 2012, 256-8). The result was the British navy tolerated an extensive trade with Germany through ports in the Netherlands and other neutral countries. Moreover, the ban on commercial dealings between British and enemy alien citizens did not, at first, apply in neutral countries outside of Europe (Wileman’s Brazilian Review, 7 September 1915; Manchester Guardian, 13 May 1915). Over the course of the conflict, as Britain moved towards total war and made an increasing number of departures from laissez-faire in the management of its internal economy, the restrictions on trade with enemy aliens became ever more severe. One political flashpoint were the London branches of the largest German banks, which were allowed to continue operating, albeit in a restricted fashion, until 1918. Although most German males in Britain had been interned as enemy aliens, the London branches of Deutsche Bank, the Dresdner Bank, and the Disconto-Gesellschaft were allowed to continue using German managers and clerks. These bankers worked under the supervision of Sir William Plender, the senior partner of Deloitte, an accountancy firm with expertise in cross-border finance (Panayi, 1991, 132-5, 142-5). The escalating British death toll on the Western Front and Zeppelin attacks on the capital itself meant that the continued presence of these branches angered many Londoners, especially those who had lost menfolk in the sanguinary British offensive launched in July 1916 (McKenna, 8 December 1916; Faber, 20 March 1918; Bonar Law, 20 March 1918). Many citizens expressing dissatisfaction with the official explanation for the continued existence of these branches, which was that “the liquidation of a banking business of an international character is of necessity an operation of the greatest complexity, and at the best of times must be spread over a very lengthened period” (Leaf and Vassar Smith, 1916, 2). Plender’s patriotism was attacked in the press (Edwards, 2004). Table 1. Trading With the Enemy Prosecutions before March 1915 Source: United Kingdom Parliamentary Papers, 9 March 1915. Nature of Charge Place of Trial of Hearing. Result. Sentence Central Criminal Court Guilty 18 months' imprisonment (upheld on appeal). Newcastle Assizes Guilty Fined £100 and costs. Attempt to purchase a large consignment of bicycle handles from Germany Smethwick Police Court Guilty Fined £500 and £101 10s. 6d. costs. Contracting (6) and (7) Manchester Guilty, (8) Police and (9) Court Dismissed Fined £50 and £52 10s. costs. Mansion House Guilty Fined £100 and £50 costs. Central Criminal Court Guilty Sentenced to 1 month Incitement for the purchase of ships from a German firm Protecting enemy's shares by transferring them to a British subject with a German firm for the supply of paper Attempting to import cocoa into Germany Paying in London for transmission to Holland the amount of a debt of au enemy owing to a Dutch firm Assisting in exporting iron ore into Germany Central Criminal Court Fined 1s. and ordered to pay costs of Guilty prosecution. Attempt to obtain pocket knives from Germany for importation to England Guildhall. Guilty 3 months imprisonment Importing steel to America, the profits to go to a German firm Obtaining lithographic transfers from Germany for use in England Guilty on 13 Manchester summonses; Police 5 Court summonses dismissed Central Criminal Court Guilty Fined £5 upon on idictment, and £1 upon remaining 12, and £105 costs. 2 months' imprisonment, and to pay costs of the prosecution. Attempt to import asbestos material from Germany Liverpool Police Court Attempt to import cotton goods from Germany via Sweden Manchester Police Guilty Court Exporting balloon silk Manchester Police Court Importing fancy leather bags into England from Germany Central Criminal Court Attempt to buy cotton for head office in Germany through neutral country Manchester Police Proceeding Court Guilty Fined £210 on three summonses, and £105 11s. costs. Fined £100 and £105 costs. Throughout the war, Addis consistently lobbied the British government for the continuation of as much trade as possible with German firms. For context, it should be explained that while German adult males in the British colony of Hong Kong had been interned by the authorities by the end of 1914 (Auswärtiges Amt, 1915), German and British citizens and firms uneasily coexisted in cities in mainland China until that country entered the war in 1917. One contemporary reported that the British mercantile community in Shanghai was divided between nationalist-minded people who patriotically wished to help their mother country and another group of individuals who wished to continue trading with their German neighbours as far as British law would permit (Not a Lawyer, May 1916). The industrialists who controlled Britain’s cotton manufacturing sector, which was concentrated in Manchester, were similarly divided as to the wisdom of a proposed law prohibiting British firms from using German distributors in China. Prior to the war, many of these textile firms had switched from British distributors in China to the more efficient and costeffective German ones. As late as the spring of 1915, many British textiles destined for retailers in the interior of China passed through the hands of German-controlled wholesale companies in Chinese ports (Manchester Guardian, 15 March 1915). In May 1915, the British government hosted a confidential conference of business leaders on the subject of trading with German firms in China. The government’s representatives began the meeting by explaining that they wished to “cut down on” the volume of trade between British and German companies in China but in a fashion that would avoid job losses in Britain’s textile manufacturing towns. It soon became evident to Addis and others in the room that the issue of whether to ban trading with the enemy in China had divided the Manchester Chamber of Commerce, with some Manchester factory owners favouring an immediate ban on all trading with Germans in China. This faction estimated that only a sixth of Manchester’s exports to China were handled by enemy alien firms and that the British trading houses in China could quickly replace the German distributors (Board of Trade, Transcript of Conference of 4 May 1915 ). Addis argued that British firms should continue to use German distributors in China. He asserted that more than half of the textiles Britain exported to China passed through the hands of German firms. Any attempt to transfer the distribution work to British houses would constitute dangerous interference with market forces. Addis reasoned that existing international division of labour, whereby the British manufactured the textiles and the German distributed them in China, as taking advantage of the comparative advantage of each nation. Addis praised the “efficiency” of the German firms in China and said that if British merchants wished to obtain more distribution work, they ought to emulate the methods and work ethic of the Germans rather than looking to the government for artificial assistance in the form of the proposed ban. The views Addis presented at the conference were entirely consistent with those Addis expressed in internal HSBC correspondence, where he wrote “I regard with equal disfavour the attempts of The China Association and others to induce the Government to boycott German firms in China. A British firm here and there might benefit by only, as you have clearly shown, at the expense of British trade in general” (Addis to Stabb, 12 March 1915.) While Addis’s major arguments in favour of continuing to trade with German firms in China were essentially economic, he also invoked morality and the sanctity of private property in “trademarks” and “goodwill” when he, declared, rather naively, that “no one would seriously contend that a state of war justifies stripping even a German of his private property” (Addis, Memorandum on Conference with Runicman and Simon 4 May 1915). Despite Addis’s speech in a favour of the continuation of trade with Germans in China, the British government decided to ban trading with enemy alien firms and citizens in that country. In the summer 1915, an era of restricted trade with the enemy began. At this point, the British government prohibited exporters in the United Kingdom from sending substantial consignments of goods to German firms in China. British cotton mills and brokers that continued to use the services of German distributors faced the threat of criminal prosecution. For instance, in November 1915 two cotton brokers were convicted and fined £100 at a trial in Manchester for sending twenty cases of shirts to a German firm in Shanghai (Manchester Guardian, 16 November 1915). The rules for British-controlled firms physically located in the Far East were different. British companies were allowed to pay dividends to German shareholders resident in China and to supply German customers with water, gas, and electric current. British subjects in China were still permitted to shop in German-owned stores and to patronise German physicians (General Licences Under King’s Regulations, No 10 of 1915). HSBC’s branches in China continued to work with German clients to help these firms to eliminate their overdrafts with the bank (Inspector’s Report on Tsingtao branch, 24 July 1915). HSBC employees also tracked down and negotiated the release of goods belonging to German firms that had been in transit to Europe at the outbreak of the war and which had been seized by the Royal Navy. These goods had been stranded in ports on the routes linking China to Europe (Inspector’s Report on Shanghai, dated 22 October 1915, 28, 29). China declared war on Germany in 1917. At that point, Chinese officials seized the assets of German firms, arrested German citizens, and made the British-legal question of trade between British and German subjects moot (Hynd to Stabb, 17 August 1917; DeutschAsiatische Bank, 1927). Throughout the war, Charles Addis also used public statements and private letters to challenge the view that the disruption of German overseas trade would benefit rather than impoverish Britain (Addis to Mills, 17 May 1919; Nicholson to Addis, 10 December 1916). Addis also firmly distinguished the German government and its property from German private firms and their assets, suggesting that while it was legitimate to try to destroy “German militarism,” it would be immoral for the British state to “prey on private property” (Paper enclosed with Addis to Mills, 9 January 1915). Addis and the Politics of British Banking After 1918, Addis’s new status as a director of the Bank of England meant that he was a prominent voice in the lively wartime debates about the future of British banking. Critics of the City of London argued that the government’s laissez-faire policy with regard to finance had resulted in the excessive growth of finance at the expense of British manufacturing. Addis’s main contribution to the national conversation about the future of banking in the postwar error was his 1918 essay Problems of British Banking. This essay, which argued the government should refrain from imposing burdensome regulations on banks, contained extensive passages in which he praised particular features of the German banking system and revealed that he had continued to follow developments in German banking since the outbreak of the war. Addis said that German banks had a “more efficient administration” than British ones becauseGerman bank boards included technical experts who were capable to evaluating loan issues. Drawing on his observations of bank board meetings in pre-war Berlin, Addis contrasted the quality of the debate with the discussions in City boardrooms. German board meetings about proposed loans were characterised by “animation” and the display of extensive “knowledge” by individual directors. A bank board meeting in London, however, involved the difficulty “of withdrawing its members even temporarily from their country pursuits” and “their obvious anxiety to lose no time in returning to them… only one or two here and there who had no train to catch are willing to discuss the matters in hand with attention.” Addis said that more generous compensation for directors might improve the quality of English bank governance by attracting talented individuals, but that English bank shareholders were reluctant to emulate their German counterparts by awarding directors higher fees. In addition to praising the German systems of bank governance and director compensation, Addis also commended the managers of the leading German banks for maintaining higher capital ratios than the leading English domestic banks (1918, 15). Addis mentioned the war had encouraged a wave of bank mergers in both Germany and England. The crucial difference between the two countries, he said, was that the newly merged banks in Germany “have increased their paid-up capital and reserves while the English banks have not.” Addis does not appear to have thought that his decision to praise the managers of Germany’s bank might have been perceived as unpatriotic in the context of ongoing slaughter on the Western Front. Ever fair-minded, Addis counter-balanced his praise for various elements of the German banking system with some comments about the benefits of Britain’s “decentralised” system of banking. Taking aim at the critics who wanted to regulate Britain’s banks so as to redirect bank lending away from foreign trade finance and towards domestic manufacturing, he said that the British tradition of “untrammelled competition” and “freedom” had made London into a global financial centre. Critics of the British banking system had noted that the German government intervenes “to ensure that the balance” between finance and industry “shall be fairly maintained” by stipulating that foreign loans issued by German banks contain a clause ensuring that related manufacturing contracts were placed with German firms. For Addis, this blurring of the lines between politics, industry, and finance was taking things too far. In this respect, he said, the pre-war British system was superior to that of Germany. The chief advantage of the British system of laissez-faire and openness was, according to Addis, that it had made London the financial centre of the world and the home of large numbers of foreign banks and commercial agencies. Commercial transactions between pairs of distant countries, he reminded his readers, was financed through credit extended in London. To illustrate this point, Addis used the example of a transaction between a Chinese merchant and a US company financed by a bill drawn on London. Prior to the war, some Britons had objected to the diversion of credit from domestic lending to the financing of trade between pairs of foreign firms on the ground that these operations did not benefit Britain’s domestic economy. To such critics, Addis replied that government intervention in international trade finance would “place in jeopardy the financial supremacy of London as the clearing house of the world. A free market means that anyone can send bills here for discount and be sure of getting gold for it when he wants it.” Addis grandly declared that “freedom is the breath of life for credit and commerce” and the “best service government can render the London money market is to leave its management and control to the bankers whose business it is to understand it” (Addis, 1918, 24-25). In his discussion of the wartime mergers of banks in Britain and Germany, Addis acknowledged that while there was often a strong business case for amalgamating banks, the current wave of bank mergers might eventually lead to increased state regulation of the financial sectors of the two countries. He reasoned that the newly-merged banks would be too big to fail and would thus enjoy a “virtual” guarantee from the State. “From government guarantees to Government control is but a step and but a step more to nationalization.” Referring to a prominent socialist intellectual, Addis wrote that “we are playing into the hands of Mr. Sidney Webb and the socialists.” Addis reported to his British readers the alarming news that the new Prussian Minister of Finance “is said to be considering a state monopoly of banking” in the country (1918, 10). Addis appears to have felt sympathy for the German bankers who were now forced to deal with this dangerous demagogue. Addis and the Carthaginian Peace Addis attempted to influence British policy towards Germany. From 1916 onwards, a political debate raged in Britain about whether punitive reparations payments should be imposed on post-war Germany. In 1916, the economists John Maynard Keynes and William Ashley had authored a government report urging that Britain not seek to impose such reparations and instead focus on reviving Anglo-German trade as quickly as possible at the conclusion of the hostilities. The debate about whether to impose a collective punishment on the German people pitted different interest groups in the British economy against each other (Bunselmeyer, 1975). Reparations were favoured by many protectionist manufacturing companies, especially those that had complained loudly about German competition before the war. Such firms demanded the peace settlement that John Maynard Keynes would famously call the “Carthaginian Peace” (Skidelsky, 1983, 386) Within the manufacturing sector, the chief proponent of soft peace terms for Germany was William Lever, the founder of Lever Brothers, a multinational soapmaking company that just happened to have a manufacturing subsidiary in the German city of Mannheim. Lever’s German factory meant that he had a compelling interest in seeing that the purchasing power of German consumers was not destroyed by the imposition of punitive reparations. In May 1916, Lever gave a public address advocating peace terms that would permit the German economy to make a speedy recovery. Paralleling arguments that were indirectly derived from Richard Cobden and Norman Angell and which were later used by Addis, Lever maintained that Germany’s economic recovery would benefit Britain as a trading nation (Knight to Lever, 15 May 1916, LBC 846). In 1918, Lever, who was now Lord Leverhulme, reiterated his support for this policy and for the restoration of international Free Trade immediately after Germany’s surrender (Leverhulme, 1918, 12-13). Addis had the opportunity to present his views, which were similar to those of Leverhulme, to senior policymakers. On 26 November 1918, Britain’s Imperial War Cabinet formed a committee to investigate the issue of a war indemnity to be levied on Germany. It was chaired by Billy Hughes, the Labor Party Prime Minister of Australia. The thinking of Hughes and many other Australian trade-unionists was strongly influenced by British Social Imperialism (Dyrenfurth, 2012), which meant that his world-view was radically different from that of Addis. Hughes, who was a staunch advocate of imposing a massive war indemnity on Germany, ensured that those who agreed with him dominated the committee. The other members of the committee on German reparations included the Finance Minister of Canada, two Conservative MPs, and two businessmen who had been handpicked by Hughes. The MPs were, according to Keynes, prominent protectionists. Prior to the war, they had demanded the introduction of protective tariffs to shut German manufactured goods out of the British market. The two businessmen on the committee, Lord Cunliffe and one Gibbs, were also noted protectionists (Skidelsky, 1983, pp 355–356). Addis testified before the British War Cabinet to the effect that any indemnity imposed on Germany should be no more than £60 million per annum. Addis claimed that Hughes and other hostile members of the committee repeatedly “heckled” him during his presentation. In his testimony, Hugo Hirst of the General Electric Company recommended that Germany be given a soft peace and a maximum reparations bill of no more than £125 million. When he reported back to the Imperial War Cabinet, Hughes was dismissive of the opinions of Addis and Hirst, noting that both men had “German interests and associations” (IWC, 24 December 1918). Ignoring the advice of Addis and Hirst, the Hughes Committee decided that Germany should be required to pay the entire costs of the war, £24 billion. The annual interest and amortization costs on this debt load would amount to £1.2billion, a figure vastly greater than that suggested by Addis (Dayer, 1988, 103). When the Paris Peace Conference was underway at Versailles, Addis and his allies in the City launched a campaign to persuade the British delegates to oppose the heavy indemnities advocated by the French. As part of this campaign, Addis presented a paper on the economics of a war indemnity to the Institute of Bankers (5 March 1919). Addis began by conceding that Germany ought to pay something in compensation to the allies. However, he stressed that while the allies might be morally right to exact a large indemnity, insisting on all of one’s moral rights was impractical. A war indemnity, he said, “should be moderate in amount and, as Bagehot said of poetry, soon over.” According to Addis, the interdependence of nations “makes it impossible to cripple Germany without to some extent crippling British trade.” The aim of policymakers, he implied, was to restore the pre-war division of labour as quickly as possible. Addis also pointed out that any German indemnity would be paid not to British individuals but to the British government, and that governments had very mixed track records in managing funds wisely. Here, Addis was arguing that the private sector in Britain would be better off if the proposed indemnity payment was left in the pockets of consumers in Germany rather than being transferred to the public sector in the United Kingdom. Classical liberalism, much like modern-day neoliberalism, is characterised by the view that it is better to allocate resources via the private sector than through the public sector. Addis’s belief in the superiority of the private sector was so strong that he was willing to leave resources in the private sector of an enemy nation than in the coffers of his own nation’s elected government. Conclusion and Implications for the Present As we have seen, Charles Addis continued to espouse ideas associated with commercial cosmopolitanism throughout the First World War. The fact he did so publicly and in a social context marked by intense xenophobia is testament to the power of the ideas that structured his thinking about the world economy. The fact he and other City figures were able to continue trading, albeit in a limited fashion, with German financial institutions is suggestive of the class and sectoral biases that influenced how the British government applied its laws against trading with enemy alien citizens and firms. What are the implications for the present of the historical research presented in this paper? In the more recent past, the members of the TCC have used ideologies such as neoliberalism to justify their activities, much as Addis and his contemporaries drew on classical-liberal principles. The ideology of neoliberalism fit the ethos of the decade or so after the end of the Cold War, when it appeared to some observers that history had ended (Fukuyama, 1989) and that that free-market capitalism was destined to dominate the world. In the 1990s, the advent of a unipolar international system characterized by a single remaining superpower and the absence of really serious conflict between the world’s leading economies reinforced this view. Some observers have concluded that we are witnessing a transition from an essentially unipolar world back to a multipolar international system (Zakaria, 2011; Ikenberry, 2013; Tyler and Thomas, 2014). Some authors have suggested that the world economy is transitioning to a period of heightened political risk, economic nationalism (Bracken et al., 2008), and the re-emergence of Great Power rivalries similar to those that led to the First World War (Glaser, 2011; Shambaugh, 2012; Coker, 2014). Many academics and policymakers have analogised the current Sino-American relationship to the pre-1914 AngloGerman relationship, noting that Germany and the United Kingdom were both geopolitical rivals and interdependent trading partners. Many find this analogy persuasive because Germany was a rising economic power, particularly in manufacturing, and was intent on challenging Britain’s longstanding international hegemony (Mearsheimer, 2010; Nye, 2014). Other observers of international business focus their concerns on Sino-Indian tensions or the relations between Russia and the NATO countries. Speaking in Davos in January 2014, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe explicitly compared his country’s current relations with China with Britain’s pre-1914 relationship with Germany. The alarming implications of his use of this historical analogy were not lost on the journalists and businesspeople who heard these remarks (Rachman, 2014). When juxtaposed against the historical research presented in this paper, Prime Minister Abe’s comments raise important questions. For instance, how would Japanese corporations with substantial investments in China respond to, say, a diplomatic crisis involving the two countries? Equally uncertain is the likely reaction of US companies such as Apple to serious naval or military tension between China and the United States. We simply do not know how Davos Man would respond to rising Great Power rivalries and the militarization of existing international tensions. The experience of the international banker Charles Addis, suggest that twenty-first century members of the TCC would be torn between the need to display loyalty to their home nation and the practical realities of running companies with complex transnational value chains. Works Cited Archival Materials “Not A Lawyer. ” (1916). (Pseudonym). Letter to Editor of the North China News, May 1916. Clipping in National Archives of the United Kingdom, Foreign Office 22/82683. Addis, C. (1915). Memorandum on Conference with Runicman and Simon 4 May 1915. In Charles Addis Papers, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, PP MS 14/495 1915 Addis, C. S. Diary.(1914-1919). Charles Addis Papers, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Addis, C. to B. Blackett. (1915). Letter of 16 December 1915. In National Archives of the United Kingdom, NAC Kew T 1/11875. Addis, C. to D. Mills. (1914). Letter of 9 August 1914. In Charles Addis Papers, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, PP MS 14/175 1914 Addis, C. to N. Stabb. (1915). 4 December 1915. In Charles Addis Records in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0029. Addis, C. to N. Stabb. (1915). Letter of 12 March 1915. In Charles Addis Records in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0029. Addis, C. to N. Stabb. (1915). Letter of 15 January 1915. In Charles Addis Records in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0029. Addis, C. to N. Stabb. (1915). Letter of 7 December 1915. In Charles Addis Records in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0029. Anonymous. (1915). “German and Austrian Firms: Extent and Nature of Trade.” 17 July 1915 in National Archives of the United Kingdom, ADM 137/2833. Auswärtiges Amt to Embassy of the United States of America. (1915). 22 April 1915. In National Archives of the United Kingdom, FO 383/33. Deutsch-Asiatische Bank. (1927). Translation of Report Issued by the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank, Shanghai for years 1915-1927 in HSBC Archive, London HQ SHGII 0578 Governor of Hong Kong to Secretary of State for the Colonies. (1915). Letter of 29 March 1915 in National Archives of the United Kingdom, Colonial Office 323/652. Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. (1915). Circular of 29 January 1915, in HSBC Archive, London, HQHSBCK 0140/GHO/0049 Circular Letters. Hynd, R.R. to N.J. Stabb. (1917). Letter of 17 August 1917. In Extracts from Shanghai s/o letter files includes correspondence between Shanghai, London and head office in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0115 Imperial War Cabinet. (1918). Discussion of 24 December 1918. In National Archives of the United Kingdom CAB23/42 Inspector’s Report on Shanghai. (1915). Report dated 22 October 1915. In HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0123. Inspector’s Report on Tsingtao Branch. (1915). Report dated 24 July 1915. In HSBC Archive, London HQ LOHII 0123. Knight to W. Lever, 15 May 1916, LBC 846. Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight. Standing Sub-Committee on the Committee of Imperial Defence. (1912). Reports and Proceedings of the Standing Sub-Committee on the Committee of Imperial Defence on Trading with the Enemy, 1912. National Archives of the United Kingdom, CAB 16/18A. Stephen to C. Addis. (1917). Letter of 5 February 1917. In Extracts from Shanghai s/o letter files includes correspondence between Shanghai, London and head office in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0115 Stephen to E. Fraser. (1916). Letter of 11 January 1916. In Extracts from Shanghai s/o letter files includes correspondence between Shanghai, London and head office in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0115 Stephen to Stabb. (1916). Letter of 16 August 1916. In Extracts from Shanghai s/o letter files includes correspondence between Shanghai, London and head office in HSBC Archive, London, HQ LOHII 0115 United Kingdom Board of Trade. (1915). Transcript of Conference of 4 May 1915. In National Archives of the United Kingdom, T 198/65. United Kingdom Government. (1914). Trading with the Enemy Act, 1914. United Kingdom Government. (1915). “General Licences Under King’s Regulations. No 10 of 1915” in National Archives of the United Kingdom, Colonial Office, 323/675. Wileman’s Brazilian Review. (1915). 7 September 1915 in National Archives of the United Kingdom, ADM 137/2833. Non-Archival Materials Anderson, O. (1967). A liberal state at war: English politics and economics during the Crimean War. London; Melbourne [etc.]: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's P.. Barrett, P.M. (2015). “Can Banks Be Held Liable for Terrorism?” 18 March 2015, Bloomberg Businessweek http://businessweekme.com/Bloomberg/newsmid/190/newsid/479. Beneria, L. (1999). Globalization, gender and the Davos Man. Feminist Economics, 5(3), 6183. Berry, C. J. (2013). The Idea of Commercial Society in the Scottish Enlightenment. Edinburgh University Press. Blaug, M. (1958). The Classical Economists and the Factory Acts--A Re-Examination. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 211-226. Bonar Law, A. (1918). Speech in Parliament. House of Commons Debates, 20 March 1918 vol 104 cc984-5. Broadberry, S., & Howlett, P. (2005). ‘The united kingdom during World War I: business as usual?’ in The Economics of World War I, Broadberry, S. N., and M. Harrison, (Eds). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 206-34. Bunselmeyer, R. E. (1975). The Cost of the War, 1914-1919: British Economic War Aims and the Origins of Reparation. Hamden, CT: Archon Books. Carroll, W. K., & Carson, C. (2003). The network of global corporations and elite policy groups: a structure for transnational capitalist class formation?. Global Networks, 3(1), 29-57. Ceadel, M. (2011). ‘The founding text of International Relations? Norman Angell’s seminal yet flawed The Great Illusion (1909–1938)’. Review of International Studies, 37(04), 16711693. Chirol, V. to G.E. Morrison. (1909). Letter of 13 September 1909 in Wood, H. J. (1977). The Correspondence of GE Morrison. Volume 1: 1895–1912. Edited by Lo Huimin. New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1976. Chirol, V. to G.E. Morrison. (1909). Letter of 19 August 1909 in Wood, H. J. (1977). The Correspondence of GE Morrison. Volume 1: 1895–1912. Edited by Lo Huimin. New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1976. Coker, C. (2014). Improbable War: China, the United States and Logic of Great Power Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dayer, R. A. (1988). Finance and Empire: Sir Charles Addis, 1861-1945. Basingstoke: Macmillan. Dayer, R. A. (2013). Bankers and Diplomats in China 1917-1925: The Anglo-American Experience. London: Routledge. Deutsch-Asiatische Bank. (1916). GeschäftS'Bericht für das Jahr 1914, Tagesordnung für dem 29. April 1916 ordentliche Generalversammlung. Berlin: Deutsch-Asiatische Bank. Deutsche Bank. (1918) Achtundvierzigster Geschäfts-Bericht des Vorstands der Deutschen Bank für die Zeit vom I. Januar bis 31. Dezember 1917. Berlin: Deutsche Bank. Dicken, P. (2010). Global Shift Mapping the Changing Contours of the World Economy. New York, Guilford Publications. Dyrenfurth, N. (2012). ‘Conscription is Not Abhorrent to Laborites and Socialists’: Revisiting the Australian Labour Movement’s Attitude towards Military Conscription during World War I. LABOUR HISTORY A Journal of Labour and Social History, (103), 145-164. Edwards, J. R. (2004). ‘Plender, William, Baron Plender (1861–1946).’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. L. Goldman. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35542 Emmett, R. B. (2011). Economics and Theology After the Separation. Available at SSRN 1951511. Erhardt, N. L., Werbel, J. D., & Shrader, C. B. (2003). ‘Board of director diversity and firm financial performance’. Corporate Governance: An International Review,11(2), 102-111. Faber, G. (1918). Speech in Parliament. House of Commons Debates, 20 March 1918 vol 104 cc984-5. Fainsod, M. (1969). International Socialism and the World War. Doubleday. Farrer, J. (2010). ‘ ‘New Shanghailanders’ or ‘New Shanghainese’: Western Expatriates' Narratives of Emplacement in Shanghai’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(8), 1211-1228. Ferguson, N. (2006). ‘Political risk and the international bond market between the 1848 revolution and the outbreak of the First World War’. The Economic History Review, 59(1), 70-112. Financial Times. (1905). ‘German Trade with China’. November 6, 1905. Findlay, R., & O'Rourke, K. H. (2007). Power and plenty: trade, war, and the world economy in the second millennium (Vol. 51). Princeton: Princeton University Press. Frieden, J. A. (2006). Global capitalism: Its fall and rise in the twentieth century. New York: WW Norton. Fukuyama, F. (1989). The end of history? (Vol. 16, pp. 3-18). National Affairs, Incorporated. Gilpin, R. (2011). Global political economy: Understanding the international economic order. Princeton University Press. Glaser, C. (2011). ‘Will China's Rise Lead to War-Why Realism does Not Mean Pessimism’. Foreign Affairs 80. Gwynne, R. Speech in Parliament. (1916). vol 87 cc450-1W House of Commons Debates, 9 November 1916 Gwynne, R. Speech in Parliament. (1916). House of Commons Debates, 14 November 1916 vol 87 cc590. Hamer, D. A. (1968). John Morley: liberal intellectual in politics. Clarendon Press Herzog, L. (2013). Inventing the market: Smith, Hegel, and political theory. Oxford University Press. Heslop, F.W. (1919). “War Indemnity And Prosperity” in Economist [London, England] 15 Mar. 1919: 448. Himmelfarb, G. (2012). The Moral Imagination: From Adam Smith to Lionel Trilling. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Höpfl, H. M. (1978). From savage to Scotsman: Conjectural history in the Scottish enlightenment. The Journal of British Studies, 17(02), 19-40. Ikenberry, G. J. (2011). ‘Future of the liberal world order: Internationalism after America’. Foreign Affairs 90, 56. Ikenberry, G. J. (2013). ‘East Asia and Liberal International Order: Hegemony, Balance, and Consent in the Shaping of East Asian Regional Order’. in Inoguchi, T., & Ikenberry, G. J. (Eds) The Troubled Triangle: Economic and Security Concerns for the United States, Japan, and China. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Ingham, G. K. (1984). Capitalism divided?: the city and industry in British social development. Macmillan Publishers Limited. James, H. (2011). ‘International order after the financial crisis’. International Affairs, 87(3), 525-537. Ji, Z. (2003). A History of Modern Shanghai Banking: The Rise and Decline of China's Finance Capitalism. Armonk, N.Y: ME Sharpe. Jones, C. A. (1987). International business in the nineteenth century: the rise and fall of a cosmopolitan bourgeoisie. Wheatsheaf books. Jones, G. (2000). Merchants to multinationals: British trading companies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (p. 1850). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jones, G., & Khanna, T. (2006). Bringing history (back) into international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4), 453-468. Jones, G., & Lubinski, C. (2012). ‘Managing Political Risk in Global Business: Beiersdorf 1914–1990’. Enterprise and Society, 13(1), 85-119. Joynson-Hicks, W. (1916) Speech in Parliament. House of Commons Debates, 8 November 1916 vol 87 cc208-9 Jung, J. (2013). ‘Political Contestation at the Top: Politics of Outsider Succession at US Corporations’. Organization Studies, 0170840613508398. Kayaoglu, T. (2010). Legal imperialism: sovereignty and extraterritoriality in Japan, the Ottoman Empire, and China. Cambridge University Press. Kennedy, G. (2014). The ‘Invisible Hand Phenomenon in Economics. Propriety and Prosperity’: New Studies On the Philosophy of Adam Smith. Kennedy, P. M. (1980). The rise of the Anglo-German antagonism, 1860-1914(pp. 18701945). London: Allen & Unwin. Kindleberger, C. P. (1986). ‘International public goods without international government’. The American Economic Review, Vol. 76, No. 1, 1-13. Kindleberger, C. P. (1986). ‘International public goods without international government’. The American Economic Review, Vol. 76, No. 1, 1-13. Kirca, A. H., Hult, G. T. M., Deligonul, S., Perryy, M. Z., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2012). ‘A Multilevel Examination of the Drivers of Firm Multinationality’. A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Management, 38(2), 502-530. Kobrak, C., & Hansen, P. H. (Eds.). (2004). European business, dictatorship, and political risk, 1920-1945. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Kroeze, R., & Keulen, S. (2013). Leading a multinational is history in practice: The use of invented traditions and narratives at AkzoNobel, Shell, Philips and ABN AMRO. Business history, 55(8), 1265-1287. Lambert, N. A. (2012). Planning Armageddon British economic warfare and the First World War. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press. Leaf, W. and R.V. Vassar Smith. (1917). Enemy banks (London agencies). Report of Messrs. Walter Leaf and R. V. Vassar Smith, with appendix, dated 12th January 1917, on the progress made in discharge of the liabilities of the enemy banks in London. London, HMSO. Leverhulme, W.H. (1918). “ Prevention of strikes” in Labour and Capital After the War, by Various Writers, with an Introduction by the Right Hon. J. H. Whitley,... Edited by S. J. Chapman. London: J. Murray. Levy, D. M. (2002). How the dismal science got its name: Classical economics and the urtext of racial politics. University of Michigan Press. Levy, J. S., & Barbieri, K. (2004). ‘Trading with the enemy during wartime’. Security Studies, 13(3), 1-47. Liébert, G. E. (1906). Rapport de Mr Liebert, Consul de France à Hongkong, sur le développement de l'action économique des Allemands dans la zone commerciale desservie par Hongkong et dans l'ensemble des mers de Chine. Saïgon: Bulletin Économique de l'IndoChine. Longstreth, F. (1979). The City, industry and the state. State and economy in contemporary capitalism, 157-90. Mak, R. K. (2004). ‘The German community in 19th century Hong Kong’. Asia Europe Journal, 2(2), 237-255. Manchester Guardian. (1908). ‘China Trade Agencies: Brazilian Coffee Markets Mail News Outward’. 17 June 1908. Manchester Guardian. (1915). ‘China Business With Germans’. 15 March 1915. Manchester Guardian. (1915). ‘Manchester and the China Trade’. 16 November 1915. Manchester Guardian. (1915). ‘Trade with Germans in China’. 13 May 1915. Manchester Guardian. (1915). ‘Trading With the Enemy: Merchants Sentences at the Assizes’. 22 February 1917. Marshall, J. N. (2013). A geographical political economy of banking crises: a peripheral region perspective on organisational concentration and spatial centralisation in Britain. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society,6(3), 455-477. McDermott, J. (1997). ‘Trading With the Enemy: British Business and the Law During the First World War’. Canadian Journal of History, 32(2). McKenna, R. (1916). Speech in Parliament. House of Commons Debates, 8 November 1916 vol 87 cc208-9 McKenna, R. (1916). Speech in Parliament. House of Commons Debates, 9 November 1916 vol 87 cc450-1W McLean, D. (1973). ‘The Foreign Office and the First Chinese Indemnity Loan, 1895’. The Historical Journal, 16(02), 303-321. Mearsheimer, J. J. (2010). ‘The gathering storm: China’s challenge to US power in Asia’. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 3(4), 381-396. Merseyside Maritime Museum (2015). Lusitania: life, loss, legacy http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/maritime/events/lusitania-listings.aspx Millar, D. (1915). Trading With the Enemy Prosecutions. Written answers (Commons) of Tuesday, 9th March, 1915. United Kingdom, House of Commons Hansard (1914-16) 5th Series, Vol. 70 Columns: 1261-1270. Millman, B. (2014). Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain. Routledge. Mollan, S., & Michie, R. (2012). The City of London as an International Commercial and Financial Center since 1900. Enterprise and Society, khr027. Morgan, G. (2012). Supporting the City: economic patriotism in financial markets. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(3), 373-387. Morris, S. (2015). “HSBC's Long List of Troubles Just Got Even Longer.” Bloomberg Business News, 10 April 2015. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-10/hsbc-slong-list-of-troubles-just-got-even-longer Morrison, G.E. to E.G. Hillier. (1909). Letter of 27 July 1909 in Wood, H. J. (1977). The Correspondence of GE Morrison. Volume 1: 1895–1912. Edited by Lo Huimin. New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1976. Morrison, G.E. to V. Chirol. (1905). 8 June 1905 in Wood, H. J. (1977). The Correspondence of GE Morrison. Volume 1: 1895–1912. Edited by Lo Huimin. New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1976. Murray, J. (2014). Evidence of a transnational capitalist class‐for‐itself: the determinants of PAC activity among foreign firms in the Global Fortune 500, 2000–2006. Global Networks, 14(2), 230-250. Nishimura, S. (2012). ‘1870-1914: An Introductory Essay’ in The Origins of International Banking in Asia: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Nishimura, S., Suzuki, T., & Michie, R. C. (Eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ohmae, K. (1990). The Borderless World: Management Lessons in the New Logic of the Global Market Place. London, Collins. Palen, M. W. (2010). Protection, Federation and Union: The Global Impact of the McKinley Tariff upon the British Empire, 1890–94. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38(3), 395-418. Panayi, P. (2014). Enemy in our Midst: Germans in Britain during the First World War. Bloomsbury Pott, F. L. H. (1928). A Short History of Shanghai, Being an Account of the Growth and Development of the International Settlement. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh. Prettyman, E. (1916). Speech in Parliament. House of Commons Debates, 14 November 1916 vol 87 cc591. Rachman, G.(2014)."Davos leaders: Shinzo Abe on WW1 parallels, economics and women at work." Financial Times, 22 January. http://blogs.ft.com/the-world/2014/01/davos-leadersshinzo-abe-on-war-economics-and-women-at-work/ Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (2003). The great reversals: the politics of financial development in the twentieth century. Journal of financial economics, 69(1), 5-50. Roberts, R. (2013). Saving the City: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914. Oxford University Press. Robinson, W. I. (2012). Capitalist Globalization as World-Historic Context: A Response. Critical Sociology, 0896920511434273. Rosenberg, E. S. (Ed.). (2012). A world connecting: 1870-1945 (Vol. 5). Harvard University Press. Rowe, W. T. (2010). China's last empire: the great Qing. Harvard University Press. Rubinstein, W. D. (1977). Wealth, elites and the class structure of modern Britain. Past and Present, 99-126. Ruparel, R. (2014). "The Battle Of Londongrad -- How Exposed Is The City To Sanctions On Russia?" Forbes, 24 March 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/raoulruparel/2014/03/24/the-battle-of-londongrad-how-exposedis-the-city-to-sanctions-on-russia/ Searle, G. R. (1998). Morality and the market in Victorian Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shambaugh, D. (Ed.). (2012). Tangled Titans: The United States and China. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Skidelsky, R. (1983). John Maynard Keynes Hopes Betrayed 1883–1920. London: Macmillan. Sklair, L. (1997). Social movements for global capitalism: the transnational capitalist class in action. Review of International Political Economy, 4(3), 514-538. Sklair, L. (2012). Transnational capitalist class. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Slater, B. (1914). ‘German Trade in China’. The Financial Times (London, England),Monday, August 31, 1914. Smith, C.T. (1994). ‘The German Speaking Community of Hong Kong, 1846-1918’. Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 34 . Trentmann, F. (2009). Free trade nation: commerce, consumption, and civil society in modern Britain. OUP Catalogue. Western Mail (Perth, Western Australia). (1915). ‘Money for Germany’. Friday 31 December 1915, page 43