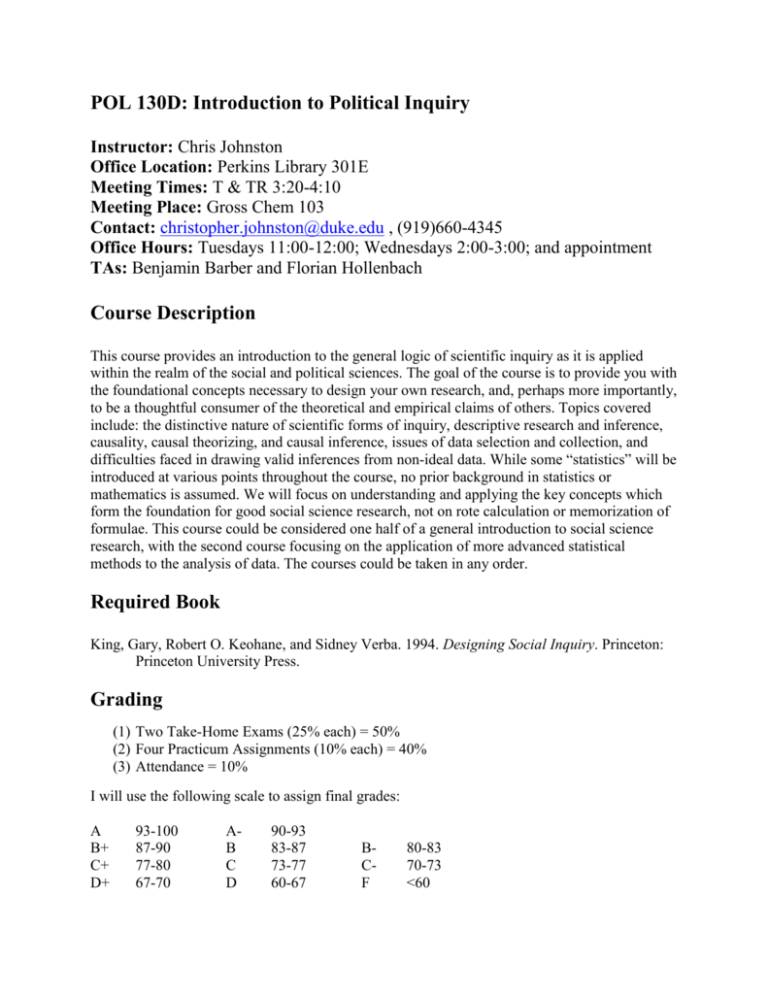

POL 130D: Introduction to Political Inquiry

Instructor: Chris Johnston

Office Location: Perkins Library 301E

Meeting Times: T & TR 3:20-4:10

Meeting Place: Gross Chem 103

Contact: christopher.johnston@duke.edu , (919)660-4345

Office Hours: Tuesdays 11:00-12:00; Wednesdays 2:00-3:00; and appointment

TAs: Benjamin Barber and Florian Hollenbach

Course Description

This course provides an introduction to the general logic of scientific inquiry as it is applied

within the realm of the social and political sciences. The goal of the course is to provide you with

the foundational concepts necessary to design your own research, and, perhaps more importantly,

to be a thoughtful consumer of the theoretical and empirical claims of others. Topics covered

include: the distinctive nature of scientific forms of inquiry, descriptive research and inference,

causality, causal theorizing, and causal inference, issues of data selection and collection, and

difficulties faced in drawing valid inferences from non-ideal data. While some “statistics” will be

introduced at various points throughout the course, no prior background in statistics or

mathematics is assumed. We will focus on understanding and applying the key concepts which

form the foundation for good social science research, not on rote calculation or memorization of

formulae. This course could be considered one half of a general introduction to social science

research, with the second course focusing on the application of more advanced statistical

methods to the analysis of data. The courses could be taken in any order.

Required Book

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

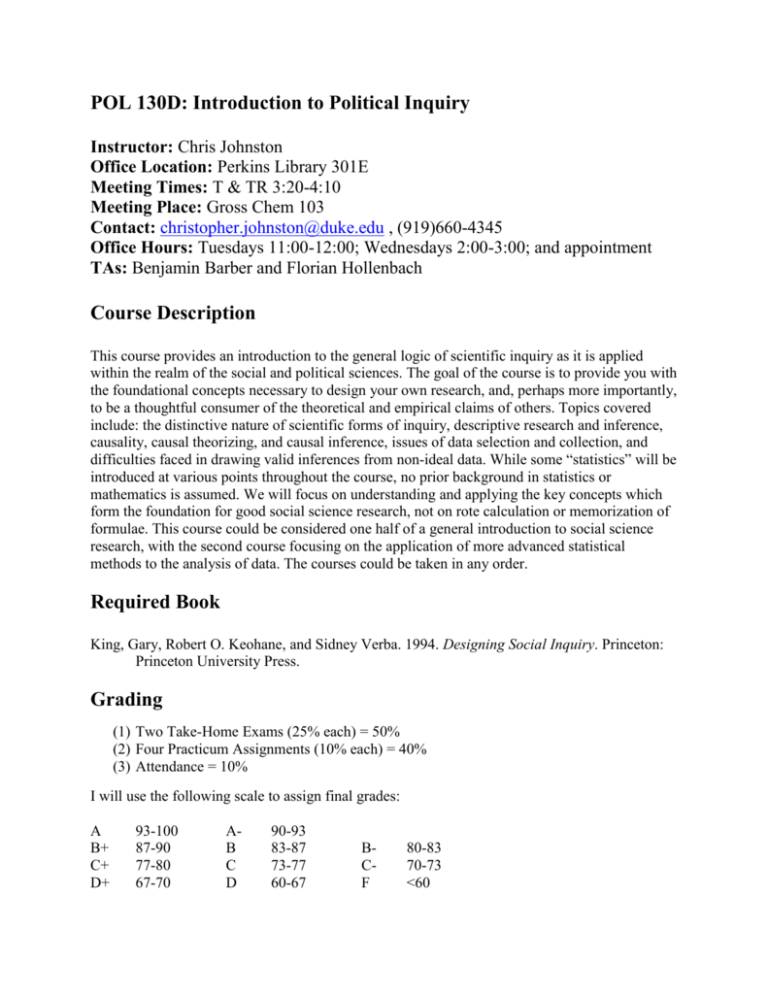

Grading

(1) Two Take-Home Exams (25% each) = 50%

(2) Four Practicum Assignments (10% each) = 40%

(3) Attendance = 10%

I will use the following scale to assign final grades:

A

B+

C+

D+

93-100

87-90

77-80

67-70

AB

C

D

90-93

83-87

73-77

60-67

BCF

80-83

70-73

<60

Attendance Policy

Attendance is 10% of your final grade, and, in addition to ensuring you do well in the course, is

an easy way to get points. Success in this course will likely be difficult without regular

attendance. I will grade attendance as follows:

(1) TAs will take attendance in sections. There are 13 total section meetings during the

semester. You may miss 3 sections (for any reason) with no penalty. After 3, your section

attendance grade will decline by one letter grade for each section missed.

(2) I will pass around an attendance sheet for each lecture, and you will sign next to your

name. You may miss 5 lectures (for any reason) with no penalty. After 5, your lecture

attendance grade will decline by half a letter grade for each lecture missed.

(3) Your final attendance grade will be a simple average of (1) and (2).

Extra Credit

Extra credit will be given for participation in departmental research projects. Students may

participate in up to three hours of projects, earning one point on their FINAL grade for each

hour. Thus, each student may earn up to three points on their final grade. As this is fairly

generous, and requires minimal time investment and effort, no other extra credit will be given;

no exceptions (except the exception below), so please do not ask.

More information on this option is available at http://www.duke.edu/web/psrp. If you wish to

participate, you can register at: http://duke-psrp.sona-systems.com. Please direct all questions

regarding the PSRP to the site administrator, David Sparks, at d.sparks@duke.edu.

The only exception pertains to the first practicum assignment, which entails making a forecast

for the 2012 Presidential Election. The student (or students in the case of a tie) with the best

forecast will receive a prize of 1 extra credit point on his or her final grade. “Best” will be

defined as the forecast closest to the actual value in absolute terms (see below for more

information).

Policy

I will follow Duke University’s procedures to establish whether absences from any event related

to this class are justified (e.g. illness, sport events) and merit ad hoc arrangements. Other than in

the very restrictive cases contemplated by the university, make up exams are not an option. Late

assignments will be reduced by one full letter grade for each day beyond the deadline.

I will also follow the University’s policy in any event of plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Grade complaints: You have the right to dispute a grade if you disagree with it. You must do so

in writing, no more than 3 working days after we have returned the exam/paper to you. Upon

receiving your appeal, I will reevaluate your grade. Please note that I will reevaluate the entire

assignment. Thus, if we have made an error in your favor, this will also be corrected.

Practicum Assignments

You are required to complete four practicum assignments that are intended to reinforce what you

learn in lecture through application to real problems in political science. Time has been allotted

to sections for developing skills relevant to these projects, and to working on them, and you

should take advantage of this. Your TAs will be a great resource for these assignments. A

description of each assignment is given below, and we will discuss each further in class and in

sections.

Assignment 1: Forecasting the 2012 Presidential Election

Your first assignment, corresponding with the Descriptive Inference section of the course, is to

generate a forecast for the 2012 Presidential Election. More specifically, you are to generate a

prediction of the difference in the proportion of the popular vote won by Obama versus Romney.

In other words, if p = the proportion of the popular vote won by Obama, and q = the proportion

of the popular vote won by Romney, you want to generate an estimate of (p – q). You should

also generate an uncertainty bound for your estimate. Finally, on the basis of your estimate and

uncertainty calculations, you should estimate the probability that Obama will win the popular

vote (i.e., that (p – q) > 0). You should use publically available polling data to generate your

estimate, and you may utilize these data any way you choose. You will be graded on your

justification for your choices as well as your calculations.

You will turn in, to be graded:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

A short paper describing what you did and why

Any data you used to generate your estimate (i.e. the raw values)

Any calculations you performed to obtain your estimate

The final forecast with an uncertainty estimate for that value, and probability of victory

You MAY NOT:

(1) Use a single, previously published forecast as your forecast (e.g., Nate Silver’s at the

NYT)

(2) Use a single, political prediction market to generate your forecast (e.g., the price of

Obama winning the election on InTrade)

(3) Copy someone else’s procedure within the class. You MAY discuss any problems or

theoretical issues in sections, with classmates, with me, and with TAs. The end product,

however, must be a result of your own efforts (e.g., data collection, calculations, paper

write-up, etc.). Note that you need to justify what you did in the paper. If you do not

understand what you did and why, this will be apparent in your write-up.

As an added incentive to do your best, the person with the “best” forecast in each section will

receive 1 point extra credit on his or her final grade for the course. “Best” will be defined as the

forecast closest (in absolute terms) to the actual difference in proportions.

Assignment 2: Estimate the Effect of One Variable on Another

Your second assignment is to estimate the causal effect of one variable on another. In other

words, your goal is to generate an estimate of what happens to some dependent variable as some

independent variable changes values. You will be graded both on execution (proper use of data,

calculations, etc.) and your justification for claiming that your estimate is a “good” one. Note

here the importance of referring to our discussions in class. If there are limitations to the

inferences you can justifiably make, you should discuss these. You may choose any question or

problem you wish. The only restriction is, as always, that you do your own work.

You will turn in, to be graded:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

A short paper describing what you did, why you did it, and a theoretical discussion

Any data you used to generate your estimate (i.e. the raw values)

Any calculations you performed to obtain your estimate

The final estimate (the estimate of the causal effect) with an uncertainty estimate for that

value

Assignment 3: Critical Analysis of a Published Research Design

For your third assignment, you will utilize our discussions in class and sections to critically

evaluate the research design of a published research article (of my choosing). Your goal is to

identify any problems with the design, and the broader implications of those problems for

making valid inferences about the parameter of interest to the authors. You will be graded on the

cogency of your arguments.

You will turn in, to be graded:

(1) A 2-4 page paper critically assessing the research design of the article

Assignment 4: Design a Study to Test a Hypothesis

For your final assignment, you will design a study to test a hypothesis of your choosing. In this

case (in contrast to Assignment 2), you must explicitly address problems of causal inference and

their potential solutions. We will discuss these in class. You may test any hypothesis you wish,

and you may test that hypothesis any way you wish. You will be graded on the logic of your

research design, and the cogency of your arguments for why your design is a valid test of your

hypothesis. The only restriction is, as always, that you do your own work.

You will turn in, to be graded:

(1) A 3-5 page paper which introduces your question, states your hypothesis, and describes

your research design and its justification.

Course Outline

8/28: Course Introduction and Syllabus

8/30: NO CLASS

8/30 and 8/31: NO SECTIONS

Why Political Science?

9/4: Why Political Science?

Watts, Duncan. 2011. “The Myth of Common Sense.”

Nyhan, Brendan. 2012. “Do Campaign Gaffes Matter? Not to Voters.”

Listen/Watch: Haidt, Jonathan. 2011. “The Bright Future of Post-Partisan Social Psychology.”

9/6: What Makes Political Science Science?

KKV: Preface & Chapter 1, pp. 3-12

Gerber, Alan S., Donald P. Green, and Christopher W. Larimer. 2008. “Social Pressure and

Voter Turnout: Evidence from a Large-Scale Field Experiment.” American Political

Science Review 102 (1): 33-48.

9/6 and 9/7: Sections

Introductions with TAs

9/11: What Political Scientists Do (Or Should Do)

KKV: Chapter 1, pp. 12-28

9/13: Recent Attacks on (Political) Science

“Amendment Offered by Mr. Flake.” Congressional Record of the U.S. House of

Representatives, 5/9/2012, pgs. H2543-H2544.

Stapel and Data Falsification

Stevens, Jacqueline. 2012. “Political Scientists are Lousy Forecasters.”

Watch: Krosnick on “Trust in Science”

9/13 and 9/14: Sections

Discussion of NSF debate, scientific integrity, etc.

Descriptive Inference

9/18: On the General and the Particular

KKV: Chapter 2, pp. 34-49

Petrocik, John R. 2009. “Measuring Party Support: Leaners are not Independents.” Electoral

Studies 28: 562-572.

9/20: Data Collection, Summary, and Statistics

KKV: Chapter 2, pp. 49-55

9/20 and 9/21: Sections

Work on Assignment 1 with TAs; collecting and organizing data from the internet

9/25: Random Variables

KV: Chapter 2, pp. 55-63

9/27: Uncertainty and Its Interpretations

KV: Chapter 2, pp. 55-63

Green, Donald P., and Bradley Palmquist. 1990. “Of Artifacts and Partisan Instability.”

American Journal of Political Science 34 (3). Read only 872-881.

9/27 and 9/28: Sections

Work on Assignment 1 with TAs; calculating uncertainty bounds for estimates

10/2: Unbiasedness

KV: Chapter 2, pp. 63-65

Erikson, Robert S., and Kent L. Tedin. 2007. “Bad Sampling: Two Historical Examples.” In

American Public Opinion, 7th edition, Robert S. Erikson and Kent L. Tedin (Eds.). New

York: Pearson Longman. (On Sakai)

10/4: Efficiency and Mean Squared Error

KKV: Chapter 2, pp. 66-74

10/4 and 10/5: Sections

Work on Assignment 1 with TAs; questions and help

Causal Inference

10/9: Counterfactuals and Causality

KKV: Chapter 3, pp. 75-85

Gelman, Andrew, and Jennifer Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and

Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Chapter 9, pages 167-173.

10/11: Causal Effects and Causal Uncertainty

KKV: Chapter 3, pp. 75-85

Fox, Richard L., and Zoe M. Oxley. 2003. “Gender Stereotyping in State Executive Elections:

Candidate Selection and Success.” The Journal of Politics 65 (3): 833-850.

10/11 and 10/12: Sections

Work on Assignment 2 with TAs; obtaining and organizing publically available data

TURN IN ASSIGNMENT 1

10/16: FALL BREAK

10/18: Assumptions for Estimating Causal Effects

KKV: Chapter 3, pp. 91-97

10/18 and 10/19: Sections

Review for exam

TAKE-HOME EXAM RELEASED ON 10/19 AFTER LAST SECTION

10/23: Unbiasedness and Efficiency for Causal Effects

KKV: Chapter 3, pp. 97-99

TAKE HOME EXAM DUE AT BEGINNING OF CLASS

10/25: Constructing Good Causal Theories

KKV: Chapter 3, pp. 99-114

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1981. “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of

Choice.” Science 211: 453-458.

10/25 and 10/26: Sections

Work on Assignment 2 with TAs; calculation of uncertainty bounds; other help

Selecting Observations for Study

10/30: Indeterminacy and Its Sources

KKV: Chapter 4, pp. 115-124

11/1: The Ideal of Random Selection

KKV: Chapter 4, pp. 124-128

11/1 and 11/2: Sections

Examples and discussion of observation-selection methods and their advantages/disadvantages

TURN IN ASSIGNMENT 2

11/6: Types of Selection Bias and Their Implications

KKV: Chapter 4, pp. 128-139

Wiblin, Robert. 2012. “Middle-Aged Not Miserable, Just Too Busy to Answer Surveys.”

11/8: Intentional Selection

KKV: Chapter 4, pp. 139-50

He, Kai. 2013. “Case Study and the Comparative Method: Why Do States Join Institutions?” In

Political Science Research in Practice, Akan Malici and Elizabeth S. Smith (Eds.). New

York: Routledge.

11/8 and 11/9: Sections

Critiquing research designs, examples and discussion

Making Good Inferences

11/13: Measurement and Measurement Error

KKV: Chapter 5, pp. 150-168

11/15: Implications of Measurement Error

KKV: Chapter 5, pp. 150-168

Sullivan, John L., James Piereson, and George E. Marcus. 1979. “An Alternative

Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s-1970s.” American

Political Science Review 73 (3): 781-794.

11/15 and 11/16: Sections

Work on Assignment 4 with TAs; issues of measurement with examples

TURN IN ASSIGNMENT 3

11/20: THANKSGIVING BREAK

11/22: THANKSGIVING BREAK

11/27: Spuriousness and Omitted Variable Bias

KKV: Chapter 5, pp. 168-185

11/29: The Logic of Control

KKV: Chapter 5, pp. 168-185

Levitt, Steven D., and James M. Snyder Jr. 1997. “The Impact of Federal Spending on House

Election Outcomes.” The Journal of Political Economy 105 (1): 30-53.

11/29 and 11/30: Sections

Work on Assignment 4 with TAs; questions and help

12/4: Endogeneity and “Reverse Causality”

KKV: Chapter 5, pp. 185-196

12/6: Control through Random Assignment (i.e. Experimentation)

KKV: Chapter 5, pp. 196-208

Druckman, James N., Donald P. Green, James H. Kuklinski, and Arthur Lupia. 2006. “The

Growth and Development of Experimental Research in Political Science.” American

Political Science Review 100 (4): 627-635.

12/6 and 12/7: Sections

Review for Final Exam

HAND IN ASSIGNMENT 4