Invasive Plants on the TCNJ Campus

advertisement

invasives.org Acer platanoides (Norway maple) Non-native Invasive Plants in Forests of The College of New Jersey Campus : A Call to Action by the students of Plants and People (BIO 315) : Osama Aly, Akua Asiamah*, Heather Brown*, Kirsten Calica, Jessica Dalpe, Camille Deering, Amanda diRenzo*, Joseph Hennelly, Michael Jung, Kelly Liszewski*, Malorie Meshkati, Emily Nowicki*, Alexandria Oliver*, Ana Park*, Sarah Sickels, Karm Trivedi, Tina Varghese, Carey Wu* (* primary authors) and Dr. Janet A. Morrison, Biology (editor) Fall 2009 1 Introduction We are students in Dr. Janet Morrison’s biology class, “Plants and People”. Throughout the semester, we have been learning about the important roles that plants can play in people’s lives, including food and medicine. Plants can also indirectly affect humans, however, through interactions within their natural environments. An example of this is non-native invasive plant species. Recently, it has come to our attention that there are a number of invasive plant species growing here on The College of New Jersey campus. Invasive species are nonnative species whose abundant presence in a particular natural environment, or ecosystem, can result in negative consequences. These can include detrimental effects to the environment and to native plants, economic harm, and harm to human health. The invasive species problem is so great that the federal government has a National Invasive Species Council (NISC) to coordinate 13 different agencies that devote resources to the problem (http://www.invasivespecies.gov) (the NISC web site is an excellent source for information on the invasive species problem and has informed this report). Invasive plants are often more aggressive than their native counterparts; they grow more rapidly and thus deprive native plants of necessary resources. They pose even greater problems to those species that are already threatened or endangered. The resulting decline of native plants has cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, since non-native invasive plants typically are poor resources for animal life, particularly insects, which themselves are food for other animals, particularly birds, and also provide essential ecosystem services such as pollination. Birds, in turn, are essential for seed dispersal for many plants. Invasive plants are often successful in new habitats because they have escaped their natural enemies with which they co-evolved in their own native range. Since there are few natural hindrances to their growth, it is therefore crucial that we take measures to prevent the spread of invasive plant species. We, as students at The College of New Jersey, feel compelled to call attention to the fact that there is an invasive plant species problem on campus. As a major land owner of natural areas, we feel that The College has a responsibility to protect the native plant species and biodiversity on campus. Not only is maintaining the ecology of these lands important, but it is also in The College’s best financial interest. Land owners that do not control the dispersal of invasive species often face more financial problems in the future, as the species become more entrenched and more difficult to eradicate. The United States loses billions of dollars each year due to unchecked invasive species. We at The College of New Jersey take pride in the beauty of our campus, and we recognize that the idea of natural beauty should include healthy wild communities as well as 2 manicured lawns and plantings. By taking action against troublesome invasive species, we can ensure that this beauty is maintained for generations to come. The necessary first step is to identify the extent of the invasive species problem within our campus natural areas. Our class chose to conduct a “bio-blitz” of TCNJ’s woodlands. This rapid assessment of the presence and abundance of species in an area provides a first look at which invasive species are present, their relative abundances, and their locations. This information can help set priorities for future management efforts aimed at reducing the impact of non-native invasive species on TCNJ’s lands. Protocol for Bio-blitz Dr. Morrison gave us a detailed invasive plant guide in order to identify non-native invasive plants in each of the four sites we blitzed. Also, in the woods behind the Music Building, she showed us how to identify the non-native invasive plants using the detailed guide we were given. This demonstration enabled us to identify non-native invasive plants correctly. We sampled five sites over two hours - the ecological study forest, the forest next to the Lake Sylva bridge, the forest across from the bridge, the forest adjacent to Lake Sylva and the right-of-way, and the forest between Lakes Sylva and Ceva. We identified the non-invasive plants using the guide, counting the number of single plants and patches of plants (when it was difficult to see distinct individuals) and recorded them on data sheets. The students worked in pairs and sampled each of the five sites by walking in parallel transects that were 2 meters wide. The 2 meter wide transects spanned the entire width of the forest site being sampled. The student pairs traversed the entire length of the site. There were 9 pairs of students performing the sampling of the nonnative invasive species of plants. The total number of hours dedicated to the sampling at the five forest sites on the TCNJ campus was 18 hours (2 hours x 9 student pairs). Results There were a total of 12 different invasive species discovered in the five sampled locations. Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) and multiflora rose (Rosa multi-flora) were present in all five sites, indicating that they are the most prevalent invasive species. Japanese stilt-grass (Microstegium vimineum) occurred in four sites; the other species were found in 1-3 of the studied sites. Norway maple (Acer platanoides) was 3 observed in just two forests, but was very abundant in both, especially in the forest between the two lakes (Table 1). The forest between the two lakes and the ecological study forest had the highest abundance of total invasive plants (Figure 1). These two sites also had the greatest species richness (number of species) (Figure 2). Table 1. Occurrence of non-native invasive plant species in five woodland sites at The College of New Jersey, Fall 2009. Species Japanese Honeysuckle Norway Maple Asiatic Bittersweet Garlic Mustard Japanese Stilt-Grass Japanese Barberry Wine Berry Autumn Olive English Ivy Winged Wahoo Multi-Flora Rose Amur Honeysuckle 4 Forest Between Lakes Single Plant Single Plant Single Plant Single Plant Single Plant Plants Patches Plants Patches Plants Patches Plants Patches Plants Patches Ecological Forest Forest by Bridge Forest Across From Bridge Lake Sylva Forest 6 11 1 2 1 0 17 26 10 36 29 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 72 35 11 7 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 17 10 0 0 3 8 4 6 3 7 0 9 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 4 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 8 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 35 26 0 0 0 0 1 0 6 10 13 8 4 1 0 1 15 6 6 5 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 2 5 NO. OF INDIVIDUALS + PATCHES 250 200 150 100 50 0 ECOL. FOREST FOREST BY BRIDGE FOREST ACROSS FOREST BY LAKE FOREST BETWEEN BRIDGE SYLVA LAKES No. of individuals + patches Figure 1. Abundance of all invasive species in each woodland. Japanese honeysuckle 100 Norway maple asiatic bittersweet 80 garlic mustard Japanese stilt-grass 60 Japanese barberry wine berry 40 autumn olive English ivy 20 winged wahoo multiflora rose amur honeysuckle 0 ECOL. FOREST FOREST BY BRIDGE FOREST ACROSS FOREST BY LAKE FOREST BRIDGE SYLVA BETWEEN LAKES Figure 2. Abundance of each non-native plant species in each woodland. 5 Discussion and Recommendations Our rapid bio-blitz assessment of non-native invasive plant species in TCNJ woodlands illustrates that our campus harbors at least 12 known invasive species that need management. In most of the sites we sampled we noted that there also was a very depauperate understory, in which the invasive plants were the most common. This observation indicates that TCNJ’s forested lands are in a state of crisis, with a significant lack of tree seedling recruitment and a lack of the plant species diversity necessary to maintain a healthy, functioning ecosystem. We urge TCNJ to develop an invasive species management plan for these woodlands. We suggest that the ecological study forest and the forest between the two lakes be the first targets since they are the most heavily impacted. We offer the following information from as a guide to management of these species. 6 Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) is a noxious, multi-stemmed, thorny, perennial shrub that is native to East Asia. It was first introduced in the late 1700s as a rootstock for ornamental rose and was widely planted as a living fence before its weedy characteristics were fully understood. The impenetrable thicket that it produces prevents access to many fields and is very costly to control. When the plant becomes established, it can produce a seed bank that can continue to produce seedlings for at least twenty years after the matured plant is removed. Young plants can be removed by hand and matured plants can be controlled through frequent cutting; herbicides can be used as well. Two naturally occurring biological controls affect multiflora rose to some extent: a native fungal pathogen (rose-rosette disease) that is spread by a tiny native mite and a nonnative seed-infesting wasp, the European rose chalcid. Winged burning bush (Euonymus alatus) is a perennial shrub native to northeastern Asia to central China. It was first introduced to North America around 1860 for use as an ornamental shrub. Once established, it can form dense thickets that displace native vegetation when planted near woodlands and pastures. It is a threat to woodland areas and fields because it out-competes native species. It can be easily controlled by weeding and herbicide may be applied if weeding is impractical. English ivy (Hedera helix) is an evergreen perennial vine that is native to Europe that was brought to the States by early settlers as an ornamental. It continues to be a popular ornamental and has been developed into a numerous varieties. Since it can grow both along the ground and climb up trees, it can displace both native ground species and can also kill trees by out-competition. controlled by cutting, grubbing, mulching and herbicidal control. 7 It can be Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) is a semi-evergreen to evergreen woody vine that was introduced from Japan in the early 1800s. Although initially valued as an ornamental, it is now planted in wildlife food plots as deer browse. It is the most commonly occurring invasive plant that is overwhelming and replacing native plants, as it occurs in dense arbors. It can be controlled with cutting and herbicides such as Escort. Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus obiculatus) is a deciduous, climbing, woody vine that was first introduced from China around 1860 as an ornamental. It has been shown to cross pollinate with American bittersweet which can potentially lead to a loss of genetic identity. Moreover, its prolific vine growth can allow it to twine into tree crowns forming thick arbor infestations which completely cover other vegetation and kill even large trees. A recommended method of control is to thoroughly wet all its leaves with a mixture of glyphosate herbicide, water and surfactant. Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a biennial herb, native to New England, that was likely introduced by settlers around 1868 for food and medicinal purposes. A high shade tolerance allows this plant to invade high-quality, mature woodlands, where it can form dense stands. These stands not only shade out native understory flora but also produce allelopathic compounds that inhibit seed germination of other species. It is also credited with the decline of the West Virginia white butterfly (Pieris virginiensis) because it produces toxic chemicals that prove to be fatal to the butterfly’s eggs. Cutting the flowering plant low to the ground in spring will prevent flowering and thus seed production. Japanese stilt grass (Microstegium vimineum) is an annual grass that is native to Asia and was introduced into North America around 1920. It commonly invades forested floodplains, ditches, forest edges, fields, and trails. It is shade tolerant and can displace native vegetation. Control methods include using the herbicide glyphosate, pre-emergent herbicides such as imazapic or pendimethalin, manual removal in mid-summer, or by mowing in late summer, before seed set. Wine raspberry (Rubus phoenicolasis) is a small, spiny perennial shrub that is native to eastern Asia and was introduced into the United States in 1890. It invades moist, open areas such as fields, roadsides, forest margins, open forests and prairies throughout the eastern U.S. It can form dense, extensive thickets that displace the native vegetation and restrict light that reaches the ground. Wine raspberry can be controlled by hand pulling or with a fork, and bagging the branches with berries to prevent spread. Chemical and mechanical methods can also be used. Amur honeysuckle can be controlled by grubbing or pulling seedlings and mature shrubs, and repeated clipping. Herbicides such as glyphosate and triclopyr can also be used. Norway maple (Acer platanoides) is a deciduous tree that is native to Europe and was first introduced into the United States in 1756, and is used as an ornamental. It has invaded forested ecosystems throughout northeastern U.S. and parts of the Pacific Northwest. It produces many seeds that are easily distributed by the wind. When it becomes established, it shades out the native understory and outcompetes native species, limiting the diversity of the area. Control methods include pulling young trees out of the ground, girdling the trunk, and cutting followed by treatment with triclopyr, a foliar herbicide. Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) is a small deciduous shrub native to Asia. It was introduced to the United States in 1863 as an ornamental. It is spread rapidly, is very shade-tolerant and forms dense stands which shade and displace native species. Control methods include manual removal, mechanical removal with a hoe, and treatments with herbicides glyphosate and triclopyr. Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) is a multi-stemmed, upright deciduous shrub that is native to eastern Asia. It was first introduced into North America in 1855, and has been planted as food and cover for wildlife as well as an ornamental. It invades open woodlands, old fields, and other disturbed areas. It spreads rapidly due to animal dispersion, and forms a dense thicket which can limit native plant growth and establishment. Autumn olive (Eleagnus umbellata) is a deciduous shrub that is native to China, Korea, and Japan. It was introduced to North America in 1830, and has been planted for mine reclamation, shelterbelts, and as a wildlife habitat. It invades old fields, woodland edges, and disturbed areas. It forms a dense layer which disperses native species and closes open areas. Repeated burning and cutting have been used to control spread, but herbicides offer more effective control. There are multiple methods to control invasive species, yet the main focus should be to avoid planting them in the first place. Many of these plants have been introduced as ornamentals, and have taken over areas by displacing native plants. Due to this fact, it should be noted that research should be done prior to planting a new species, and 8 native species should be planted instead. For invasive species that are already present on the TCNJ campus, it is recommended that further research be done to determine the best way to eliminate them. Biological controls are usually the best way to eliminate an invasive species, yet most of the aforementioned species do not have known ones. The use of herbicides should be utilized as a last resort. TCNJ expends considerable resources to maintain and beautify the developed part of the campus, but little to nothing on its natural areas. It is no longer possible in a suburban landscape to let nature takes its course if the goal is to maintain the native integrity of species diversity, which is crucial for ecosystem function and maintenance of necessary ecosystem services. Suburban woodlots face a dual, probably linked, challenge of invasion by non-native species and severe impacts from deer overabundance. Management of deer is a separate and vexing issue, but in the small parcels of woodlands that TCNJ owns, management of invasive plant species is achievable. As a major landowner in Ewing, TCNJ could be a leader in this aspect of environmental stewardship. 9

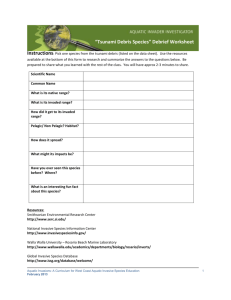

![[Type text] [Type text] Prof. Sandy M. Smith's Invasive Species Lab](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008211227_1-e00888e6c97e7f0ad17a5ec826a8ce37-300x300.png)