Reconstructed-Narratives-of-Embodiment-James

advertisement

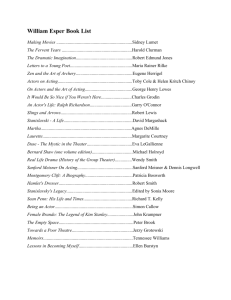

TaPRA 2013, Glasgow Performer Training Working Group Reconstructed Narratives of Embodiment: The Meisner Technique through Sanford Meisner on Acting By James McLaughlin . Sanford Meisner published only one book during his lifetime that was simply called, Sanford Meisner on Acting. In the introduction of this book, he hints at two earlier attempts to set his Technique in print. The first only came to two chapters that he abandoned because he did not understand them upon rereading. The second was never published, primarily because it lacked, ‘the drama inherent in our interaction’ (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: xviii). By way of explanation, he notes that, ‘the confessional mode is impossible to sustain at length in the theater, which is an arena where human personalities interlock in the reality of doing’ (ibid). Meisner’s analysis of the failure of his two earlier attempts of writing about his Technique suggests that the form of Sanford Meisner on Acting, a partly constructed narrative description of a year in one of his classes, edited and embellished by Dennis Longwell, is chosen deliberately and is necessary to successfully convey the Technique. There are of course powerful echoes of Stanislavsky’s choice to describe his System through a narrative account of a fictional classroom. However, it should not be assumed that Meisner is simply aping the Russian, to whom he acknowledges a great debt (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 137). The failure of the first two books that Meisner claims to either have not understood upon rereading, or that failed to make, ‘sufficiently apparent’, how he was able to, ‘uniquely transmit [his] ideas’, points to a much more powerful imperative for the form the book took. This suggests that the Meisner [1] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. Technique exists not only in the principles that underpin it, but also in the way those principles are imparted. This suggestion is strengthened by the divergence of the way his Technique is taught by his successors (Shirley, 2010: 210). From this we can conclude that it is not just the principles (or the content) of the Technique that is important, but also the larger situation in which those principles are transmitted. To capture the broad experiential dimension of the Meisner Technique I will be applying a selection of phenomenological perspectives to this discussion. These phenomenological interpretations are not the only way of looking at the Meisner Technique; an interesting alternative view is offered by Jonathan Pitches in Stanislavsky in America where he argues that, ‘the Meisner actor seems to be the very embodiment of the Watsonian Behaviourist project whose central concept … was to: “Avoid mentalistic concepts such as sensation, perception and emotion, and employ only behaviour concepts such as stimulus and response”’ (Pitches, 2006: 123). Pitches takes the, ‘action and reaction pattern that is first experienced in the Repetition Exercise’ (ibid), as the primary evidence of this in Meisner’s Technique and makes a compelling argument from the scientific perspective that he is occupying. Just as in any situation where foreign theory is applied to performance practices, it is important to remember that Meisner himself was neither a phenomenologist, nor a behaviourist, but a pragmatic acting teacher. However, these theoretical perspectives can both help us to understand processes operating at a deep level within the Meisner Technique. This paper arose from my PhD research in which I examined the phenomenal dynamic of Sanford Meisner’s technique of acting and its resonances with postmodern performance. It occurred to me in the course of this work that the narrative form of Sanford Meisner on [2] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. Acting had a particular power to communicate the spirit of the Meisner Technique as I learnt it from Michael Saccente, one of Meisner’s students. Once I had completed my phenomenal analysis of the Technique I felt an urge to return to this book to see if I could discover how it created this effect. In the course of trying to answer this question I discovered the work of Richard Gerrig, a cognitive psychologist whose work focuses on the intersection of art and psychology, and whose arguments and theories are routinely backed up with experimental data. Gerrig opens the door to the application of narratives to the transmission of acting methodologies in his 1993 work, Experiencing Narrative Worlds, where he notes: In many respects, the task of the reader is much like the task of the actor. Consider this excerpt from Constantin Stanislavski’s classic volume, An Actor Prepares: “We need a broad point of view to act the plays of our times and of many peoples. We are asked to interpret the life of human souls from all over the world. An actor creates not only the life of his times but that of the past and future as well. That is why he needs to observe, to conjecture, to experience, to be carried away with emotion.” Readers are called upon to exercise exactly this same range of skills. They must use their own experiences of the world to bridge gaps in texts. They must bring both facts and emotions to bear on the construction of the world of the text. And, just like actors performing roles, they must give substance to the psychological lives of characters. (Gerrig, 1993: 17) It is clear from this excerpt that Gerrig’s argument draws on the activity of acting to illustrate certain features of the experience of narratives. My intention with this paper is oriented in the opposite direction; I will draw on the processes of narrative experience to show how they might be applicable to the transmission of the Meisner Technique of acting. It should be noted that Gerrig is activating a particular paradigm of acting, as exemplified by An Actor Prepares, and what we might describe as modern, realistic drama, but as my point [3] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. of departure this does not determine the more specific arguments I will be setting forth here. From Gerrig’s analyses, there are three features of narrative experience that show it to be a particularly effective means of transmitting acting methodologies such as the Meisner Technique. The first is the very active nature of the experience of narratives, requiring the participation of the reader and therefore their virtual embodiment of the processes involved in an acting methodology contained within it. Secondly, narrative experience activates the perspective of the individual reader, a process that is also vital to the actor according to the Meisner Technique. Thirdly, Gerrig’s experiments show that narrative experience has measurable effects on real-world judgements and actions at a pre-conscious level, the dimension on which the Meisner Technique focuses. As this list makes clear, my focus here is on the Meisner Technique in particular, and I will explore the possibilities and difficulties of extending this to other methodologies once I have laid this argument out. Gerrig was intrigued by the recurrent reports of readers that they had been ‘transported’ by narratives and therefore set out to delineate the cognitive processes involved in this experience. The first important discovery that Gerrig makes is that the process of experiencing narratives is an active one. Therefore, rather than simply receiving the meaning intended by an author and passively being ‘transported’ into an imaginary world of someone else’s construction, the reader actively constructs this world and ‘transports’ themselves into it. Such a perspective picks up on a strong current within reader response theory, but is original in the extent to which it analyses the detail of the reader’s activity through the application of theory, and through experimental means. [4] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. Further to Gerrig’s invocation of Stanislavski, he claims that when they experience narrative worlds, ‘readers perform narratives’ (Gerrig, 1993: 12). When performing a narrative, a reader is called upon to actively engage with it, to be responsible for their own experience. Therefore, in Sanford Meisner on Acting, a reader is called upon to imaginatively construct the room in which the class is taking place, to endow the teacher and students with a semblance of life, and to live through the events of the narrative with them. Rather than passively absorbing information, Gerrig’s theory demonstrates that the reader actively participates in the narrative. Given this, the reader is going one step further than the claim, common to reader response theory, that the reader creates the meaning out of the text. In the terms of Gerrig’s discussion, readers do not create a body of objective knowledge, somehow separate from themselves, but instead establish a new set of relationships between themselves and the world that now includes elements that they have created out of the text. This distinction is important because rather than simply increasing their knowledge, they are forging new involvements. Gerrig proves that the reader participates in narratives by identifying ‘Participatory Responses’ in them. These p-responses, ‘refer to the non-inferential responses that … arise as a consequence of the readers’ active participation’ (Gerrig, 1993: 66). Gerrig distinguishes p-responses from inferential responses because they ‘do not fill gaps in the text’ (ibid), meaning that they are not strictly necessary in order to make sense out of the narrative. He notes that p-responses vary in the extent to which they arise unconsciously, or as the result of ‘more effortful problem solving’ (Gerrig, 1993: 68). In all cases along this continuum however, p-responses enable, ‘readers [to] draw themselves solidly into the narrative world’ (Gerrig, 1993 : 96). [5] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. For those who come to Sanford Meisner on Acting with the intention of learning or reinforcing their understanding of the Meisner Technique, the likelihood that they will exhibit p-responses is increased. This is because their intention is also the apparent intention of the students within the narrative. Gerrig notes that such, ‘identification promotes an investment of resources toward p-responding’ (Gerrig, 1993: 82). In other words, because the specially interested reader shares an intention with the characters within the narrative, they are more likely to participate imaginatively within it. Along with the p-responses that arise unconsciously during the experience of the narrative, a narrative in which characters with who the reader identifies are set tasks to complete towards the attainment of their shared intentions also calls into play the ‘more effortful’ p-responses associated with problem solving. Thus as Meisner sets his class the task of finding an Independent Activity that is difficult, urgent, and that they must complete for a compelling personal reason (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 39), the reader who is trying to grasp the material is encouraged to think of tasks that might fulfil those criteria for themselves. Such moments of activity draw the reader into the narrative world, increasing the investment they have in it and in turn increasing the degree of identification they are able to experience with the students it portrays. In the start of a positive feedback loop, this identification further ‘promotes an investment of resources toward p-responding’ and so cycles back through the process again. Gerrig identifies a particularly productive form of p-response that arises as events in the narrative are revealed. He notes that, ‘once readers are made privy to particular outcomes, they mentally begin to comment on them, often engaging in an activity I call replotting … [through] which readers consider alternatives to the real events’ (Gerrig, 1993: 90-91). He [6] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. later specifies that replotting is, ‘often a specific, directed use of readers’ power to carry out simulations’ (Gerrig, 1993: 93). If the reader of Sanford Meisner on Acting has been presponding sufficiently to the narrative, when Meisner discusses the reason for an exercise failing (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 42-3), they might simulate an iteration of the exercise in which the same mistakes were not made. Such simulations that require the creation of moments that are not necessary to make sense of the narrative, but provide a fuller grasp of the methodology which is its subject, are one way that narratives have a particular power to transmit acting methodologies such as the Meisner Technique. These simulations are reminiscent of the second stage of Husserl’s transcendental phenomenological reduction, that he calls, ‘criticism of the transcendental experience’, or the ‘eideitic reduction’ (Husserl, 1995: §13). This process involves the phenomenological investigator freely imagining variations of their direct perceptual experience in order to come to an understanding of the necessary and sufficient conditions that define that type of experience. It is this step in Husserl’s phenomenology that allows the analysis of the phenomenologist to move beyond the particularities of their experience and to establish a more universal description of experience. This analogy is relevant to us here because the simulations that the reader runs in their replotting activity function in a similar way by allowing them to move beyond the particular events conveyed in the narrative to a broader and deeper understanding of the type of experience is describes. Therefore, just as Husserl moves from his own perceptual experience of listening to a melody (for instance), to a theory of listening to melodies in general through his eidetic reduction (Husserl, 1991: §11), the replotting that the reader engages in allows them to move from an experience of the particular events of Sanford Meisner on Acting to a broader grasp of the Technique. [7] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. By invoking the intentions of the reader to illustrate how p-responses can be reinforced by identification with characters within the narrative world, we have already seen how the individual perspective of the reader can have an effect on the extent to which the narrative might affect them. However, in the case of the Meisner Technique the activation of the individual’s perspective has a much greater resonance. Meisner’s programme, from the observation exercises, through Repetition and Independent Activities, stresses that what matters in the student’s work is not the ‘right’ or ‘correct’ answer, but what they perceive of the world around them (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 19). Meisner repeatedly makes it clear to his students that their acting should spring from what matters to them, what gives them the impulse to act (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 157). Every observation they make of their environment, or their fellow performer in the advanced Repetition exercise, is couched in terms of how they see it (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 21). This stress on the impulses and feelings of the individual actors might easily be interpreted as a reification of the ‘essential self’ of the actor, but might just as legitimately be seen as an awakening of perspective that shifts the focus away from the actor’s self as a centre of meaning and disperses it into the relationships the actor has with their environment and their fellow performers. Because Sanford Meisner on Acting transmits the Meisner Technique via a narrative, the reader’s individual perspective is activated by both the general processes of narrative cognition and the processes of the Meisner Technique that it describes. In this way Sanford Meisner on Acting is encouraging a pre-conscious sympathy with the nature of the Meisner Technique and helping readers to grasp it before they consciously and objectively understand it. [8] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. This distinction between grasping the Meisner Technique subjectively and objectively understanding it is fundamental to this discussion. Sanford Meisner is at pains to stress that he is, ‘a very non-intellectual teacher of acting. [His] approach is based on bringing the actor back to his [sic] emotional impulses and to acting that is firmly rooted in the instinctive’ (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 37). This principle is ingrained in every stage of Meisner’s training, from the earliest observation exercises through Repetition and Independent Activities, and into scene work. Accordingly, the Meisner Technique is based in a holistic, phenomenological engagement with the world rather than a more logical, rational approach of the sort that objective knowledge might generate. I would argue that rather than applying a rational formula to the craft of acting, Meisner is training his actors to interact with their environment in a way that is compatible to Merleau-Ponty’s theories of worldly engagement such as ‘the intentional arc’. Merleau-Ponty describes the power of this concept in the following passage from Phenomenology of Perception: ...the life of consciousness–cognitive life, the life of desire or perceptual life–is subtended by an ‘intentional arc’ which projects round about us our past, our future, our human setting, our physical, ideological and moral situation, or rather which results in our being situated in all these respects. It is this intentional arc which brings about the unity of the senses, of intelligence, of sensibility and motility. (Merleau-Ponty, 2002: 157) This makes it clear that it is the intentions of the subject that determine their perception of the world they inhabit and therefore their, ‘physical, ideological and moral situation’, as well as, ‘the unity of the senses, of intelligence and motility’ (ibid). Therefore, according to Merleau-Ponty, when Meisner bases his acting methodology in the subjective realm of instinct and impulse, he is empowering the intentional arc to alter that student’s perception of reality – to literally shift their perception of their physical, ideological and moral situation through a manipulation of their intentions. When we draw into this picture the fact that the [9] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. readers’ intentions, arising from their subjective perspective, are able to draw them into the narrative world through the instruments of identification and p-response, we can see that the narrative form allows Meisner to activate his readers’ subjective perception of the world in order to instinctually grasp his methodology, just as his training process does in his classroom. It might initially seem counterintuitive that an inanimate book might hold the power to alter reader perceptions to the extent that they are able to virtually embody the Meisner Technique of acting. It is more in line with common sense that by reading a book we are able to gain abstract knowledge, to add to the store of facts we have of a given subject. According to such an account, the idea that one might practically grasp the significant elements of a craft such as acting, that involves the whole body and mind in its practice, from a book is absurd. If a narrative was simply a list of facts and information that the reader acquires and retains in abstract storage until it can be applied through the body, this might be the case. However, as Gerrig has shown, narratives allow readers to ‘transport’ themselves into narrative worlds by harnessing their intentions to enhance identification and the production of p-responses. Because the Meisner Technique is deliberately nonintellectual, and works on the instinctual dimension of the actors’ subjectivity, the imaginative embodiment of the Technique through participation within the narrative is an ideal way to approach the Technique. This leads to the question of whether grasping the Meisner Technique through the experience of narrative could ever be as effective as studiobased learning at the hands of a good teacher. Of course there are many facets of training where actual psychophysical practice cannot be rivalled. For instance, there is a huge difference between how we may believe we are behaving and how others interpret our [10] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. behaviour. Much of the text of Sanford Meisner on Acting, and much of the footage from the Masterclass DVD, involves Meisner clarifying and correcting the intentions and behaviour of his students when they believe that they had been performing appropriately. As Nick Moseley recognises, ‘the process is endlessly diagnostic, and each actor engaging in it has to be side-coached and nurtured through each stage, otherwise the work can result in little more than confusion and frustration’ (Moseley, 2012: 8). The psycho-physical doing and the objective judgement of these attempts is one feature of studio work that could never be replaced by the experience of narrative worlds. However, there are aspects of the Technique that might be transmitted more effectively by the experience of narrative worlds than by direct studio-based work. These arise because narratives are inherently distillations of reality; moments are selected for representation and others are omitted, leaving the reader to fill in the gaps with inferences and presponses. In this way, narratives direct the perception of the reader to what the author wants them to perceive. However, as we have argued in this paper, how the reader perceives those events, how they bridge these episodes to construct a coherent account, what replotting they engage in – in short the whole narrative world that forms around these selected moments – are determined by the reader’s unique perspective. The reality of the studio on the other hand is constituted by a much denser milieu of perceptions, time flows more evenly rather than collecting around significant moments, and attention is much less forcibly directed. The actor in the studio is therefore forced to sort through, distil, and construct their own interpretation of the Meisner Technique from a confusing collection of perceptions. Of course, this is exactly where the role of the teacher in the studio is vital. If the teacher is able to ‘side-coach’ and ‘nurture’ the student through the confusing and [11] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. potentially frustrating phases of the Technique, they are able to accomplish just what the narrative does when it directs the readers’ focus to particular moments and offers potential ways of understanding them. The added benefit, as I mention above, is that in the studio the psycho-physical doing and interactive judgement and analysis provide an even stronger basis for inhabiting and knowing the Technique. However, even when undertaking studio training with a very good teacher, by complementing this with the experience of another classroom and further iterations of scenarios and the ‘interlocking’ of different personalities in the ‘reality of doing’, the student’s grasp of the Technique has the potential to be enhanced. Studio work and narrative experience might therefore be seen to constitute two valuable tools for the training of Meisner actors. By alternating between the two routes to learning the Technique, the student might broaden and strengthen their grasp of it. My suggestion that the experience of the narrative of Sanford Meisner on Acting might have an effect on the reader’s real world grasp of the Meisner Technique is reinforced and taken one step further by Gerrig’s discovery that narratives can affect the real world judgements of readers at a pre-conscious level. His arguments for this conclude that, ‘persuasion by fiction is the default position’ (Gerrig, 1993: 227, original emphasis). He draws on Gilbert’s Spinozian concept of belief fixation when he claims that, ‘acceptance of belief is an automatic concomitant of comprehension. “Unacceptance” may follow later, but the initial product of cognitive processing is a belief in the understood propositions’ (ibid). Gerrig sums up his position by saying that, ‘the account I am advocating, therefore, replaces a “willing suspension of disbelief” with a “willing construction of disbelief.” The net difference is that we cannot possibly be surprised that information from fictional narratives has a real world effect’ (Gerrig, 1993: 231). Although Gerrig is talking about blatantly fictional [12] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. narratives here, his argument applies to all narratives, fictional and non-fictional, but specifies fiction in this instance because it is the type of narrative most commonly accused of having no real world effects. Gerrig’s discussion here is especially relevant to transmitting the Meisner Technique because of Meisner’s preference for what he calls, ‘actor’s faith’. Meisner’s wonder and admiration are easy to detect when he tells his class of an instance when Eleanor Duse began to blush in the middle of a scene as the character she was playing was embarrassed. Meisner tells his class that this reaction, ‘came from living truthfully under imaginary circumstances. Preparation could never have induced that. It came from her genius, her completeness in living truthfully under imaginary circumstances’ (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 87). On another occasion he explains why he considers Maureen Stapleton, who premiered the lead role in Tenesse Williams’, The Rose Tattoo, and won an academy award for her performance as Emma Goldman in Reds, to be an exemplary actress: “She has great actor’s faith,” Meisner says. “What is actor’s faith?” “She believes that the imaginary circumstances are truer than true,” Joseph says. “Let’s just say that she believes they are true. What else? Ralph?” “You’re willing to believe it even though you may doubt that it’s true.” “A real actor finds a way of eliminating the doubt.” (Meisner and Longwell, 1987: 61) These examples might allow us to summarise Meisner’s definition of ‘actor’s faith’, as a quality that allows the actor to believe the imaginary circumstances to be true and to live through those circumstances truthfully. What is striking about such a definition is that there is apparently no pretence involved. Instead the actor has a pre-conscious acceptance – a belief without doubt – that the circumstances that govern their character apply to them personally. Many of the exercises in Meisner’s training programme are explicitly designed to train and nurture this quality, and it is therefore a crucial element of the Technique that [13] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. any method of transmission must find a way to inculcate. The ‘belief fixation’ that makes belief in the truth of a narrative the ‘default position’ of cognitive processing is particularly well-suited to achieve this as it trains the reader to accept the truth of the narrative without doubt, an acceptance that is mirrored in the processes that the actors within the narrative are trying to learn. The Spinozian assertion that, ‘acceptance of belief is an automatic concomitant of comprehension’, would also apply to non-narrative tracts that present facts in a more objective manner, but the instruments of identification and p-response that draw the reader into the world of the narrative reinforce this ‘acceptance of belief’. Again we can see that a narrative medium facilitates the subjective orientation of the reader in just such a way as the exercises within Meisner’s class do for his students. This is a further reason that the experience of narrative worlds is a fitting method of transmitting acting methodologies such as the Meisner Technique. As I mention above, a non-narrative book may be able to participate in some of the processes that I am discussing here, but only to a limited extent. This is not to say that such a book is inferior, only that it takes a different route to the transmission of the Technique and has a different set of strengths that a narrative book does not possess. An excellent case in point is Nick Moseley’s 2012 book, Meisner in Practice. This volume is subtitled, ‘A Guide for Actors, Directors and Teachers’, and as such it is without peer in the cluster of works published about the Meisner Technique. The only account that comes close to the style of Moseley’s work is the brief chapter in Mel Gordon’s, Stanislavsky in America, where he provides a brief contextualisation of Meisner’s work and a short instruction of how to execute the Repetition exercise (Gordon, 2010: 176-180). Meisner in Practice takes this to significantly greater depths by working through the different stages of the training and [14] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. providing at each, ‘description, analysis and practical example’ (Moseley, 2012: viii), of the processes under discussion. As a guide for actors, directors and teachers, it is an invaluable tool as it allows the various practitioners objective insight into the purpose, operation, and effects of the various parts of the training. This is of tremendous worth for those seeking to solve particular acting dilemmas, communicate effectively and practically with actors, and plan dynamic workshops. What it does not do, that a more narrative medium such as Sanford Meisner on Acting does, is to subjectively orient the reader to the processes involved in the Technique. Moseley’s guide is an excellent example of a book that provides a store of objective knowledge that must then be translated into embodied knowledge through direct application in the studio. Where Sanford Meisner on Acting is different is that it bridges the gap between theory and practice from the outset, allowing the reader to virtually embody the processes of the Meisner Technique purely through an investment in the narrative world it presents. As I note above, this knowledge must also be actualised in the studio, but I would argue that it orients the student more effectively to a pre-conscious sympathy for the approach Meisner advocates. Another example that highlights the processes I am discussing by its contrast to them is the 2006 DVD, Masterclass, released by The Sanford Meisner Centre. This DVD centres around eight hours of footage of Meisner’s teaching intercut with an interview with Martin Barter, a senior teacher at The Sanford Meisner Centre. The resulting work has an effect similar to Moseley’s Meisner in Practice, in that it presents practical examples, descriptions and brief analyses of the major aspects of Meisner’s training. However, because the practical examples are not embedded within a narrative frame the viewer is prevented from investing in them to the extent that they are able to when reading Sanford Meisner on [15] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. Acting. The DVD allows the viewer to objectively understand the various exercises and to see how they are applied in the studio, but does not encourage them to subjectively grasp the exercises as the narrative does. However, just as Nick Moseley’s book is especially useful for certain purposes, this DVD is the most detailed record of Meisner’s pedagogical techniques and would be a perfect resource for a prospective teacher who is attempting to grasp the ‘nurturing’ and ‘side-coaching’ that Moseley identifies as essential for the teaching of the Technique. As a second contra-example, Masterclass demonstrates exactly where the experience of narrative worlds might be useful in the transmission of acting methodologies. Where Masterclass offers a host of principles and examples of their application, Sanford Meisner on Acting brings together the objective principles and subjective understanding so that when it comes time to apply the theory in practice the reader has already integrated elements of the Technique into their perception of the world. The experience of the narrative world allows the reader to shape their intentional arc in such a way that makes the practical application of the Technique more natural by engendering in them a pre-conscious sympathy for its processes. This paper has been intentionally limited in terms of its application. As I stated in the introduction, my background and research interest is in the Meisner Technique in particular. I have argued that it is the phenomenological orientation of this acting methodology that makes it particularly well-suited to being grasped through narrative experience. So much of the Meisner Technique is about the imaginative perception of reality and therefore a medium that brings the student to the Technique in a similar manner undoubtedly has an advantage over one that functions more objectively. For more systematic approaches, that access the actors’ rational faculties more than their subjective instinct, this will not be the [16] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. case. Those methodologies that consider themselves more ‘outside-in’, than ‘inside-out’, that are influenced by Diderot and Brecht, or that prioritise system and logic over feeling and intuition, are outside of the scope of these arguments. Constantine Stanislavski provides an interesting case that is most clearly defined in the debate between the ‘Method of Physical Actions’ and ‘Active Analysis’. Kedrov’s application of Stanislavski in the ‘Method of Physical Actions’ relies on a mechanistic picture of acting and ties into interpretations of Stanislavski’s work as a ‘System’. Maria Knebel’s ‘Active Analysis’ on the other hand, uses the physical score that a role offers, but adds to this the ‘character’s rhythmic energy and trajectory of desire’ (Carnicke, 2009: 191). This approach allows actors to, ‘draft performances by exploring the dynamics of human interaction through improvisation’ (Carnicke, 2009: 3). This more subjective, intuitive, and experiential approach to a role is closer to my interpretation of the Meisner Technique and might therefore be more susceptible to the arguments I have presented here. What makes Stanislavski’s case particularly interesting is that out of Creating a Role, An Actor Prepares, and Building a Character, only the first is presented in a direct, nonnarrative style. This might suggest that Stanislavski came to appreciate the benefits that a narrative presentation of his acting methodology might offer as his teaching and writing evolved. This debate, however, is much broader than the parameters of this paper. What I hope to have laid out here is a solid basis for the suggestion that certain aspects of particular acting methodologies, such as the Meisner Technique, might be particularly well transmitted by narratives. The reasons that this is so are embedded in the cognitive processes involved in experiencing narrative worlds, specifically that this experience is active, awakens the subjective perspective of the reader, and has measureable effects on [17] ©James McLaughlin, 2013. real-world judgements. These findings can be interpreted from a selection of phenomenological perspectives that allow us to connect the cognitive processes of narrative experience to the phenomenal dynamics involved of the Meisner Technique. These arguments suggest that narrative experience is a particularly productive method to transmit aspects of subjective, intuitive performance methodologies. This might have implications for the teaching of acting within institutions and studios, suggesting a greater role for narratives to assist students situate themselves imaginatively within the particular worldly engagements demanded by particular acting methodologies. Bibliography Carnicke, Sharon Marie. (2009). Stanislavsky in Focus: An Acting Master for the Twenty-First Century. Second Edition, Routledge: London. Gerrig, Richard J. (1991). Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading. London: Yale University Press. Gordon, Mel. (2010). Stanislavsky in America: An Actor's Workbook. London: Routledge. Husserl, Edmund. (1991). On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time. J. Brough (trans.). Dorcrecht: Kluwer. Husserl, Edmund. (1995). Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology. D. Cairns (trans.). Dorcrecht: Kluwer. Meisner, Sanford. (2006). Sanford Meisner: Masterclass, [DVD] The Sanford Meisner Centre, Open Road Films. Meisner, Sanford and Longwell, Dennis. (1987). Sanford Meisner on Acting. New York: Vintage Books. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. (2002). Phenomenology of Perception. Colin Smith (trans.). London: Routledge. Moseley, Nick. (2012). Meisner in Practice: A Guide for Actors, Directors and Teachers. London: Nick Hern Books. Pitches, J. (2006). Science and the Stanislavsky Tradition. Routledge: London. Shirley, D. (2010). '"The Reality of Doing": Meisner Technique and British Actor training' in Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 1:2, pp.199-213. [18] ©James McLaughlin, 2013.