El Libertador del Norte y El Libertador del Sur - Course

advertisement

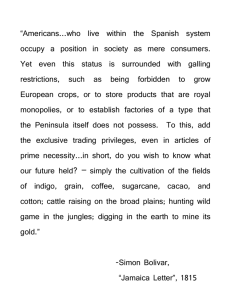

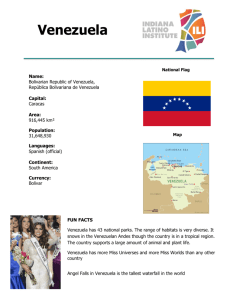

El Libertador del Norte y El Libertador del Sur Simon Bolivar and Jose de San Martin lived during roughly the same time period and both worked toward Latin American independences. Simon Bolivar lived from 1783 to 1830, and, known as the “El Liberator,” he is most famously associated with Venezuela’s liberation. His methods and motives were differing from that of San Martin, evident by the peoples’ reactions to his attempts. He became a lieutenant coronel in a junta that, in 1811, declared the First Republic of Venezuela after taking Caracas from the Spanish. He ruled Venezuela for a short time, but rebellion soon forced to flee to New Granada. From this point he initiated his first introduction of outside help to liberate Venezuela. Through his Cartagena Manifesto Bolivar explained to the Colombians that it would benefit them in the future fighting to aid Venezuela now. They avidly responded, and with their help he took Caracas back in 1803. Once again he ruled as a dictator for a short time before a royalist group forced him to flee to Jamaica. In Jamaica he spread his government ideas through his “Jamaica letter,” and he petitioned for support in Haiti after that. Eventually he took Venezuela again in 1816. He also became president of a new country dubbed Gran Colombia, which included Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador. It was during his next ambition, to liberate Peru, that he crossed paths with San Martin. After he achieved that, he attempted to return to his presidency of Gran Colombia, but it was falling apart, including the receding of Venezuela and Ecuador. In 1830, he was exiled yet again but soon died. He was buried in Colombia, too, since Venezuela refused to allow him to be buried on their land. In conclusion, he was unpopular at the beginning and end of his quests, but his actions in between aided Latin America. Jose de San Martin was born in 1778 and died in 1850. He is loosely called the Liberator of the South, being known primarily for freeing Argentina. Unlike Bolivar’s guerilla warfare, San Martin was a military man. He initially served under the Spanish in wars against the French and later in opposition against Napoleon. He left for Buenos Aires in 1811 after resigning from his military career in Spain. He was immediately accepted and ordered by the government to create a cavalry to be known as the Mounted Grenadiers. He soon led the group to success against Spanish ships in 1813, and, in 1814, obtained leadership over another part of Buenos Aires’ army. His next ambition included the seizure of Lima, Peru’s capital. The plan was to enter via the Andes through Chile, so he and 4,000 men began the trek in January of 1817. A month later, San Martin was declared Supreme Dictator in the city of Santiago de Chile, which he resigned, allowing Bernardo O’Higgins to be elected. Opposition struck in 1818 when Spanish forces attacked the city, but the Argentine-Chilean army was able to defeat them in the battle of Maipu, silencing Spanish advancements into Chile. A water-way path to take Lima was opened, and in 1820 a new fleet was built and on route to Lima. San Martin successfully proclaimed independence in Lima and is designated Protective of Peru in 1821. In 1822, as mentioned before, San Martin and Bolivar meet privately for more than four hours. The result is the “retirement” of San Martin, who resigns later that year and returns to Buenos Aires. After his wife’s death in 1823, he and his little daughter moved to France, where he lived until his death in 1850. pg. 1 Bolivar accomplished much in his life and certainly held great ambitions for Venezuela’s independence. However, he had a less of a public appeal than San Martin, who was regarded with admiration all his life. San Martin also began on the Spanish side, fighting in their military while Bolivar was born in Venezuela. San Martin experienced relatively more success and was never exiled. Bolivar, on the other hand, was exiled 3 times from his own country before his death. San Martin was more solely interested in people’s liberation rather than ruling them. Bolivar, however, ruled as dictator on numerous and brief occasions. Bolivar’s more impulsive ways led to a less consistent strain of success, and San Martin’s method was more effective but had to develop over time. Works Cited pg. 2 Nosostro, Rit. "Simon Bolivar." HyperHistory.net. 2 Sept. 2010. Web. 27 Nov. 2011. <http://www.hyperhistory.net/apwh/bios/b4bolivarsimon.htm>. "Biography of San Martin (summary)." La Página De Pablo A. Chami. Web. 27 Nov. 2011. <http://pachami.com/English/ressanmE.htm>. "José De San Martín vs. Simón Bolívar." Coursework.Info. 25 Mar. 2004. Web. 27 Nov. 2011. <http://www.coursework.info/GCSE/History/Modern_World_History/Vietnam_19541975/Comparative_Essay__Jos_eacute__de_San_Ma_L61563.html>. pg. 3