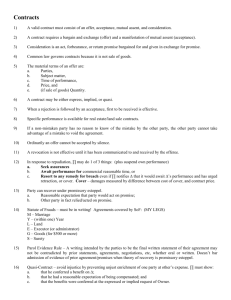

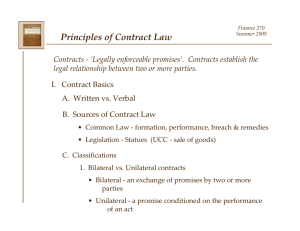

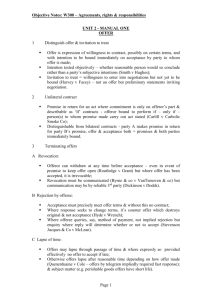

- UVic LSS

advertisement