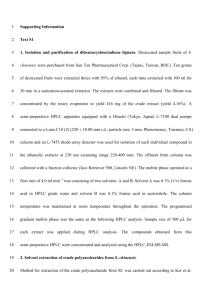

Specialist Assessment and Interventions Program (SAIP) Report

advertisement