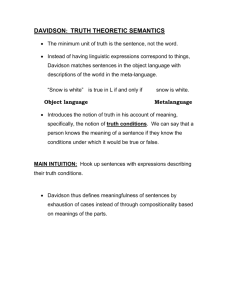

Objectivity and Skepticism: Davidson versus

advertisement