Comprehensiveness of Care: Concept and Importance

advertisement

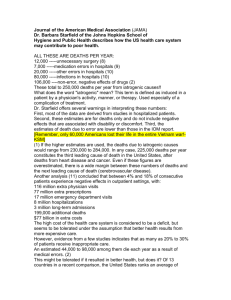

Comprehensiveness of Care: Concept and Importance Barbara Starfield, MD Presented at: RNZCGP Annual Quality Symposium Wellington, NZ February 14, 2009 “Basic Coverage” versus Comprehensive Primary Care “Basic coverage”: e.g., all ages, care by doctors, hospitals, prescription drugs, lab/diagnostic tests. (HEALTH SYSTEM responsibility) Comprehensive primary care: a range of services broad enough to care for all health needs except those too uncommon to maintain competence. (Who provides and Where) Starfield 01/09 COMP 4117 What Is Comprehensiveness in Primary Care? Dealing with all health-related problems or interventions except those too uncommon to maintain competence (“common” = encountered in at least one per thousand patients in a year) Starfield 01/07 COMP 3536 Comprehensiveness is the feature of primary care practice that is most salient in distinguishing primary care-oriented countries from other countries. Starfield 01/07 COMP 3571 System Features Important to Primary Health Care Resource Allocation Progressive Cost Compre(Score) Financing* Sharing hensiveness Belgium France Germany US 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0** 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 Australia Canada Japan Sweden 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 Denmark Finland Netherlands Spain UK 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 0 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 Sources: Starfield. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Oxford U. Press, 1998. van Doorslaer et al. Equity in the Finance and Delivery of Health Care: An International Perspective. Oxford U. Press, 1993. *0=all regressive 1=mixed 2=all progressive **except Medicaid Starfield 11/06 EQ 3500 n Criteria for Comprehensiveness In US studies: universal provision of extensive and uniform benefits for children, the elderly, women, and other adults; routine OB care; mental health needs addressed; minor surgery; generic preventive care In European studies: treatment and follow-up of diseases (e.g., hypothyroidism, acute CVA, ulcerative colitis, workrelated stress, n=17); technical procedures (e.g., wart removal, IUD insertion; removal of corneal rusty spot; joint injections); taking cervical smears; group health education; family planning and contraception Sources: Starfield &Shi, Health Policy 2002; 60:201-18; Boerma et al, Br J Gen Pract 1997; 47:481-6; Boerma et al, Soc Sci Med 1998; 47:445-53. Starfield 10/07 COMP 3891 Specialty services are more costly than primary care services, both from the systems viewpoint and from the viewpoint of individuals followed over time. This is especially the case for medical subspecialists. Sources: Starfield & Shi, Health Policy 2002; 60:201-18. Franks & Fiscella, J Fam Pract 1998; 47:105-9. Baicker & Chandra, Am Econ Rev 2004; 94:357-61. Starfield 05/06 SP 3417 Although specialists usually do better at adhering to disease-oriented guidelines, generic outcomes of care (especially but not only patient-reported outcomes) are no better and are often worse than when care is provided by primary care physicians. Studies finding specialist care to be superior are more likely to be methodologically unsound, particularly regarding failure to adjust for case mix. Sources: Hartz & James, J Am Board Fam Med 2006; 19:291-302. Chin et al, Med Care 2000; 38:131-40. Donohoe, Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:1596-1608. Bertakis et al, Med Care 1998; 36:879-91. Harrold et al, J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14:499-511. Smetana et al, Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:10-20. Other studies reported in: Starfield et al, Milbank Q 2005; 83:457-502. Starfield 04/07 SP 3700 Resource Use, Controlling for Morbidity Burden* • More DIFFERENT specialists seen: higher total costs, medical costs, diagnostic tests and interventions, and types of medication • More DIFFERENT generalists seen: higher total costs, medical costs, diagnostic tests and interventions • More generalists seen (LESS CONTINUITY): more DIFFERENT specialists seen among patients with high morbidity burdens. The effect is independent of the number of generalist visits. That is, the benefits of primary care are greatest for people with the greatest burden of illness. *Using the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACGs) Source: Starfield et al, Ambulatory specialist use by patients in US health plans: correlates and consequences. J Ambul Care Manage 2009 forthcoming. Starfield 09/07 CMOS 3854 SP 2964 • The higher the ratio of medical specialists to population, the higher the surgery rates, performance of procedures, and expenditures. • The higher the level of spending in geographic areas, the more people see specialists rather than primary care physicians. • Quality of care, both for illnesses and preventive care, are no better in higher spending areas, and in most cases are worse. (Data controlled for sociodemographic characteristics, co-morbidity, and severity of illness) Sources: Welch et al, N Engl J Med 1993; 328:621-7. Fisher et al, Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:273-87. Baicker & Chandra. Health Aff 2004; W4(April 7):184197 (http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/reprint/hlthaff.w4.184v1.pdf). Starfield 09/04 04-145 SP 2964 Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons Task Force to Review Fundamental Issues in Specialty Education GENERALISM SPECIALISM Knowledge Breadth Depth Multidisciplinary Single discipline Undifferentiated Differentiated Prevention, investigation/ management/ rehabilitation and chronic care Investigation/management Disease is considered in the context of multiple systems and the whole. Disease is considered in the context of a single system. Community- and hospital-based Hospital-based Skills Predominantly non-invasive Predominantly invasive Attitudes Holistic Reductionist Starfield 01/09 SP 4085 Comprehensiveness is a critical feature of primary care because it is responsible for avoiding referrals for common needs in the population and hence for saving unnecessary expenditures. Comprehensiveness is measured by the availability in primary care of a wide range of services to meet common needs, and by demonstrating that care is, indeed, provided for a broad range of problems and needs. Starfield 09/08 COMP 4065 Assessment of Comprehensiveness • Assess the range of services available in primary care: diagnosis and management of all common problems in the population, mental health problems, minor surgery, indicated screening for disease, common minor procedures, common follow-up needs. (Normative measure) • Determine the cumulative percentage contributed by visits for the most common problems. The higher the percentage, the greater the breadth of services provided. (Empirical measure) Sources: Rivo et al, JAMA 1994; 271:1499-1504. Boerma et al, Br J Gen Pract 1997; 47:481-6. Starfield 01/07 COMP 3538 Comprehensiveness in Primary Care Wart removal IUD insertion IUD removal Pap smear Suturing lacerations Tympanocentesis Removal of cysts Vision screening Joint aspiration/injection Foreign body removal (ear, nose) Setting of simple fractures Sprained ankle splint Age-appropriate surveillance Family planning Immunizations Smoking counseling Remove ingrowing toenail Hearing screening Behavior/MH counseling Home visits as needed Electrocardiography Nutrition counseling Examination for dental status OTHERS? Starfield 03/08 COMP 4008 In New Zealand, Australia, and the US, an average of 1.4 problems (excluding visits for prevention) were managed in each visit. However, primary care physicians in the US managed a narrower range: 46 problems accounted for 75% of problems managed in primary care, as compared with 52 in Australia and 57 in New Zealand. Source: Bindman et al, BMJ 2007; 334:1261-6. Starfield 01/07 COMP 3537 Assessment of Comprehensiveness May Differ from Place to Place Comprehensiveness means that primary care meets all health-related needs of the population except those that are too uncommon to maintain competence. This will differ from place to place. Starfield 04/04 04-047 2817 COMP Primary Care Oriented Health Services CAPACITY Provision of care PERFORMANCE Receipt of care HEALTH STATUS (outcome) Biologic endowment and prior health Source: Starfield. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Oxford U. Press, 1998. Personnel Facilities and equipment Range of services Organization Management and amenities Continuity/information systems Knowledge base Accessibility Financing Population eligible Governance Problem recognition Diagnosis Management Reassessment Community resources Cultural and behavioral characteristics Person-focused relationship Utilization Acceptance and satisfaction Understanding Participation Longevity Comfort Perceived well-being Disease Achievement Risks Resilience Social, political, economic, and physical environments Starfield 04/08 HS 4139 n The Health Services System: Comprehensiveness Range of services CAPACITY Provision of care Problem recognition PERFORMANCE Receipt of care HEALTH STATUS (outcome) Source: Starfield. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Oxford U. Press, 1998. Starfield Starfield1999 1999 HS 99-014 1441 PCAT: Comprehensiveness Subdomains Services available Services provided (received) Starfield 01/02 02-022 PCM 2047 Primary Care Domains and Subdomains: Comprehensiveness Comprehensiveness: services available • Availability of 11 specific services, e.g., family planning. Comprehensiveness: services provided • Services received from the primary care source, e.g., discussions of ways to stay healthy. Starfield Starfield05/96 1996 PCM 96-24 1017 PCAT: Comprehensiveness (Services Available*) Following is a list of services that you or your family might need at some time. For each one, please indicate whether it is available at your PCP’s office. 1. 2. 3. 4. Family planning or birth control methods Counseling for mental health problems Sewing up a cut that needs stitches Vision screening *Examples Starfield 01/02 02-027 PCM 2052 PCAT: Comprehensiveness (Services Provided*) In visits to your PCP, are any of the following things discussed with you? 1. Advice about healthy foods and unhealthy foods 2. Ways to handle family conflicts that may arise from time to time 3. Advice about appropriate exercise for you 4. Checking on and discussing the medications you are taking *Examples Starfield 01/02 02-028 PCM 2053 Specialist societies are often strong enough to prevent primary care from providing services that are provided in primary care elsewhere and despite evidence that they can be provided safely in primary care. • • • • • • monitoring anticoagulant therapy in atrial fibrillation routine colonoscopy early voluntary abortion management of insulin-dependent diabetes (Belgium) reduction of dislocated toe injection of vitamin B12 in iatrogenic pernicious anemia secondary to gastric bypass • H. pylori screening Sources: Heneghan et al, Lancet 2006;367:404-11. Wilkins et al, Ann Fam Med 2009;7:56-62. Shaw et al, Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:369-74. Gervas J, Personal communication 2008. Shaffrey TA, Personal communication 2009. Starfield 01/09 SP 4118 We know that 1. Inappropriate referrals to specialists lead to greater frequency of tests and more false positive results than appropriate referrals to specialists. 2. Inappropriate referrals to specialists lead to poorer outcomes than appropriate referrals. 3. The socially advantaged have higher rates of visits to specialists than the socially disadvantaged. 4. The more the training of MDs, the more the referrals. A MAJOR ROLE OF PRIMARY CARE IS TO ASSURE THAT SPECIALTY CARE IS MORE APPROPRIATE AND, THEREFORE, MORE EFFECTIVE. Source: Starfield et al, Health Aff 2005; W5:97-107 (http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/reprint/hlthaff.w5.97v1). van Doorslaer et al, Health Econ 2004; 13:629-47; Starfield 08/05 SP 3241 Use of Specialists in the US • REFERRAL rates from primary care to specialty care in the US are HIGH. • Between 1/3 and 3/4 (depending on the type of specialist) of visits to specialists are for routine follow-up. • The percentage of people SEEN BY a specialist in a year is high, especially in the presence of high morbidity burden. Sources: Forrest et al, BMJ 2002; 325:370-1. Valderas et al, Ann Fam Med 2008, in press. Starfield 03/06 SP 3396 Percentage of People Seeing at Least One Specialist in a Year US Canada (Ontario) 40% of total population; 54% of patients (users) 31% of population (68% at ages 65 and over) UK about 15% of patients (at ages under 65) Spain 30% of population; 40% of patients (users) Sources: Peterson S, AAFP (personal communication, January 30, 2007). Jaakkimainen et al. Primary Care in Ontario. ICES Atlas. Toronto, CA: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2006. Sicras-Mainar et al, Eur J Public Health 2007; 17:657-63. Starfield et al, submitted 2008. Starfield 01/07 SP 3529 n Patients receiving care from specialists providing care outside their area of specialization have higher mortality rates for community-acquired pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Source: Weingarten et al, Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:527-32. Starfield 09/04 04-141 SP 2963 The greater the co-morbidity, the greater the chance of referral in individual visits. The more common the condition in primary care visits, the less the likelihood of referral, even after controlling for a variety of patient and disease characteristics. When co-morbidity is very high, referral is more likely, even in the presence of common problems. Source: Forrest & Reid, J Fam Pract 2001;50:427-32. Starfield 01/09 RC 4119 How Frequently Do Specialists Take Care of People with “Specialty” Conditions? % of episodes Cardiologists 36% of those with cardiac disease Orthopedists 22% of of those with musculoskeletal disease Neurologists 40% of those with nervous system disease Factors other than age, gender, and overall “morbidity burden” determine whether a patient will be seen by a specialist or not, and how much it will cost. Episodes in which a specialist is seen are more expensive. Source: Spitzer, ACG Users Conference, 9/2000. Starfield Starfield10/00 2000 SP 00-078 1744 Expected Resource Use (Relative to Adult Population Average) by Level of CoMorbidity, British Columbia, 1997-98 Acute conditions only Chronic condition High impact chronic condition None 0.1 Low 0.4 Medium 1.2 High 3.3 Very High 9.5 0.2 0.2 0.5 0.5 1.3 1.3 3.5 3.6 9.8 9.9 Thus, it is co-morbidity, rather than presence or impact of chronic conditions, that generates resource use. Source: Broemeling et al. Chronic Conditions and Co-morbidity among Residents of British Columbia. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, 2005. Starfield 09/07 CM 3867 n Management focused primarily on diseases does not make sense for primary care. The benefits of primary care (person-focused, comprehensive, and coordinated) are greatest for people with high morbidity burdens. This is at least part of the reason why disease management has not proven useful in improving health. Even the chronic care model will not be useful unless it is carried out in the context of good primary care. Sources: Mangione et al, Ann Intern Med 2006;145:107-16. Tsai et al, Am J Manag Care 2005;11:478-88 Starfield 01/09 D 4108 Comprehensiveness in primary care is necessary in order to avoid unnecessary referrals to specialists, especially in people with co-morbidity. Starfield 02/09 COMP 4148 Assessment of Specialty Care Orientation • percentage of population seeing one or more specialists in a year • visits to specialists per person in a year • percentage of patients seeing one or more specialists in a year • visits to specialists per patient per year • percentage of patients referred in a year • ability of patients to go directly to specialists for new and/or re-visits) ALL of the above are also relevant for the type of specialist, and for the reason for visit. Starfield 04/07 SP 3636 Proposed Benefits of Subspecialization • • • • • • • • Quicker potential access Improved patient and/or practitioner satisfaction Make primary care more intellectually rewarding Reduced referrals to secondary care Career development (circular reasoning!) Improved communication with specialists* Clinical benefits* Financial benefits* *No evidence to date Source: based on Leese, Comprehensiveness v special interests: Family medicine should encourage its clinicians to subspecialize. In Kennealy & Buetow. Ideological Debates in Family Medicine. New York, NY: Nova Publishing, 2007. Starfield 01/07 SP 3524 Evidence on the Impact of Subspecialization • Increases referrals without improving outcomes • Increases costs and administrative challenges • May improve patient’s view of access to care • Practitioners may function more as specialists than as primary care physicians. Source: Starfield & Gervas, Comprehensiveness v special interests. Family medicine should encourage its clinicians to specialize: Negative. In Kennealy & Buetow, Ideological Debates in Family Medicine. New York, NY: Nova Publishing, 2007. Starfield 01/07 SP 3549 Making More Efficient Use of Specialists • Consider when specialist referrals can be avoided by direct consultation between the primary care physician and the specialist, without the patient having to be present. • Develop a strong secondary (community) level of care for diagnostic testing. • Periodic specialist (secondary level) visits to primary care, perhaps involving group visits where appropriate. Starfield 01/07 SP 3533 Questions Needing Answers 1. Is the greater use of diagnostic technology among specialists only because of higher prior probability of a positive result, or is there some inherent predisposition to using diagnostic tests among specialty-oriented physicians? Starfield 02/03 03-041 SP 2425 Questions Needing Answers 2. Is co-morbidity associated with more hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC) because there is simply more pathology or because medical care does a poor job of detecting and treating co-morbidity? 3. Can we clearly specify what it is that specialists can do that primary care physicians can’t do? Starfield 02/03 03-042 SP 2426 Questions Needing Answers 4. At what time during an episode of illness should one refer to a specialist? How can this appropriate time be measured? 5. Is there evidence for a threshold of frequency such that something is too rare for primary care physicians to maintain competence? 6. Is it good (or bad) that the rich see specialists more than the poor? Starfield 02/03 03-043 SP 2427 Augmenting the Potential of Primary Care: Comprehensiveness • Caring for all but uncommon conditions Starfield 08/02 02-140 2166 COMP Primary Care Orientation of Health Systems: Rating Criteria • Practice Characteristics – First-contact – – – – – Longitudinality Comprehensiveness Coordination Family-centeredness Community orientation Source: Starfield. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Oxford U. Press, 1998. Starfield Starfield11/02 11/02 PC 02-406 2367sc n Primary Care Scores, 1980s and 1990s 1980s 1990s Belgium France* Germany United States 0.8 0.5 0.2 0.4 0.3 0.4 0.4 Australia Canada Japan* Sweden 1.1 1.2 1.2 1.1 1.2 0.8 0.9 Denmark Finland Netherlands Spain* United Kingdom 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.7 1.7 1.5 1.5 1.4 1.9 *Scores available only for the 1990s Starfield 07/07 ICTC 3758 n Practice Characteristics (Rank*) System (PHC) and Practice (PC) Characteristics Facilitating Primary Care, Early-Mid 1990s 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 GER FR BEL US SWE JAP CAN FIN AUS SP DK NTH UK 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 System Characteristics (Rank*) *Best level of health indicator is ranked 1; worst is ranked 13; thus, lower average ranks indicate better performance. Based on data in Starfield & Shi, Health Policy 2002; 60:201-18. Starfield 03/05 ICTC 3099 n Distribution of Reasons for Referral: Badalona, Spain Diabetes 24.4% (ophthalmology) Local inflammation/mass 16.5% (dermatology) 10.7% (general surgery) 13.0% (dermatology) 11.5% (ophthalmology) Molluscum contagiosum Visual signs and symptoms Lipoma Benign/undefined skin neoplasia 11.4% (general surgery) 10.8% (dermatology) Auditory signs and symptoms 10.5% (ENT) Notes: 1. More than one reason is common. 2. Although orthopedic referrals are the most common specialist referrals, the percentage of reasons for any one is low. Starfield 01/07 SP 3530 Condition-specific Analysis of Referral Rate by Practice Prevalence for Selected Conditions with Adequate Sample Size (n=65) NOTE: The data are from the 1989 to 1994 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys. Axes are on the logarithmic scale. Medical conditions are represented by the circles, surgical conditions by the triangles, and other conditions (gynecologic and psychosocial) by the squares. EDC denotes expanded diagnosis clusters. Source: Forrest & Reid, J Fam Pract 2001; 50:427-32. Starfield 01/09 RC 4124 Average Number of Visits Per Year to Primary Care and Specialists by Morbidity Burden, Co-morbid Conditions, Managed Care Organizations, 1996 9 Mean Number of Visits 8 7 5.68 6 * 5 4.32 3.46 4 * 3 2 1 1.69 1.81 * 0.68 0 Low-medium High Very high Morbidity Group *p<.0001 Primary Care Physician Based on data in Starfield et al, Ann Fam Med 2003; 1:8-14. Specialist Starfield 08/08 SP 4054 n Average Number of Visits Per Year to Primary Care and Specialists by Morbidity Burden, Co-morbid Conditions, Medicare 8.95 9 * Mean Number of Visits 8 6.57 7 6 5 3.9 * 4 3 2 2.12 4.32 * 1.8 1 0 Low-medium High Very high Morbidity Group *p<.0001 Primary Care Physician Source: Starfield et al, Ann Fam Med 2005; 3:215-22. Specialist Starfield 08/08 SP 4055 n Co-morbidity and Volume of Visits to Primary Care Physicians The number of visits to primary care physicians for OTHER conditions is greater than the number of visits to specialists for OTHER conditions AND the number of visits to primary care physicians for OTHER conditions is greater than the number of visits for the index condition. Starfield 04/01 01-062 1869 CMOS Co-morbidity and Visits to Specialists For most common chronic conditions, non-elderly people with a lot of comorbidity see specialists less than primary care physicians for BOTH the index and OTHER conditions. For elderly patients with high and very high co-morbidity, use of specialists (at least in the US) is much greater. Starfield 09/03 03-147 2530 CMOS Co-morbidity: Conclusions about Use and Type of Services • Primary care providers are the major providers of care BOTH for index and chronic conditions and for OTHER conditions, in people with all degrees of co-morbidity, EXCEPT for uncommon conditions, e.g., diabetes in children. • Disease case management by specialists in the condition does NOT appear to be an appropriate strategy. Co-morbidity is what drives the difference in number of visits to both primary care physicians and specialists. Starfield 04/01 01-063 1870 CMOS