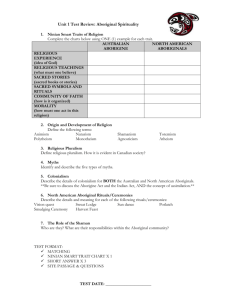

Aboriginal Beliefs and Spiritualities

advertisement

STUDIES OF RELIGION II PRELIMINARY Australian Aboriginal Beliefs and Spiritualities - The Dreaming ABORIGINAL HISTORY In Australia for at least 40 000 years – some say up to 100 000 years Origins uncertain Isolated for long period of time – developed culture and ways of living in isolation Some contact with Muslim people to north in what we now call Indonesia Before arrival of white people Aboriginal life was Nomadic or semi-nomadic Hunting and gathering Use of stone tools and wooden implements MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT ABORIGINES Apparently simple lifestyle of Aborigines led to misconceptions: That they were culturally uniform That they had little attachment to the land and made little use of it James Cook in his exploration of Australian coast described the land as terra nullius (Latin for ‘empty land’) This was despite opposition he received from Aborigines at places where he landed, e.g. Botany Bay DIVERSITY AMONG ABORIGINAL PEOPLE Diversity always part of Aboriginal society At time of white settlement there were 700 languages or dialects – now less than 250 Also diversity in songs, stories, dances, ceremonies, paintings – but also common features among Aboriginal society especially related to the highly developed, religious and complex associations with nature and land Archaeological evidence shows Aboriginal culture has altered and developed over long period of time WHO IS AN ABORIGINE? Two separate groups make up original Australians Aborigines Torres Strait Islanders Between these two groups and within the groups there are distinct differences in culture Indigenous Australia is sometimes used to refer to all these groups of Australians This is reflected in national body called ATSIC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission) SOME STATISTICS Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in 2001 Census is 460 140 Most live in New South Wales and most Aborigines live in urban centres Population before white settlement was in range of 315,000 – 1,000,000 Aboriginal population declined dramatically after European settlement as result of disease, brutal treatment, dispossession and social and cultural disruption and disintegration More recent times have seen large increase in Aboriginal population in Australia Distribution of Aboriginal Population 2001- ABS DREAMING Aboriginal spirituality takes many forms including many Aboriginal forms, the form of the Torres Strait Islands and European religious culture But most Aboriginal spirituality comes from a sense of belonging to the land or sea or to other people or to a person’s culture Although there are differences the common thread through all Aboriginal spirituality is ‘dreaming’ Dreaming is centre of Aboriginal religion and life explaining how the world works DREAMING – A DEFINITION Dreaming: A complex concept of fundamental importance to Aboriginal culture, embracing the creative era long past (when ancestral beings roamed and instituted Aboriginal society) as well as the present and the future DREAMING “Dreaming is the beginning of all things. It is when all the things we know in the world today were formed. More correctly, Dreaming refers to events and places rather than what Westerners would call time. The Aboriginal sacred stories are stories about events of the Dreaming and how Ancestor (Spirit) Beings formed the land, and founded life on the land.” W.H. Stanner DREAMING Dreaming is experienced in stories, songs, dances, art, symbols and rituals and ceremonies Dreaming is intimately related to the land - not just soil but the whole environment including people Humans are not seen to be separate from the land - Aborigines are part of the land and the land is part of them ‘THE’ DREAMING ‘The’ Dreaming is the whole complex of ideas, stories, ceremonies which is linked to the beginning of all things ‘The’ Dreaming tells the story of the creation but it is not limited to the past ‘The’ Dreaming is past, present and future ‘MY’ DREAMING ‘My’ dreaming may include the stories associated with the form of life with which ‘I’ am connected - e.g. the black swan, the eagle, the dolphin. ‘My’ Dreaming connects me back to ‘the’ Dreaming ‘My’ dreaming would be depicted for me in art and objects and in ceremonies DREAMING – PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE Leads to following beliefs of Aboriginal religion: Ancestral beings eternally leave the world full of signs of their goodwill towards the people they have also brought into being. If these people, with the wisdom about living given to them, can interpret outward signs to say that they have to follow a continuing pattern, then they will live always under the assurance of good fortune Humans, made up of material and spiritual elements, have value for self and others, and there are spirits who care for them Main religious rituals are to renew and conserve life, including life-force that keeps inspiring word in which humans live are bonded in soul and spirit DREAMING – PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE Material part of life, including humans, under a discipline that requires people to understand sacred tradition of the group and to conform to the pattern of the tradition Life is a mixture of good and bad, joy and suffering, but all is to be celebrated Major rituals convey a sense of mystery by symbols points to ultimate or metaphysical realities that show themselves by signs Metaphysical: Those things that relate to the origin and structure of the universe and beyond the physical nature, e.g. time, space, cause, identity, essence World order comes from events where ancestral beings travel and transform themselves into sites – the ancestors have always existed – no question of who made them The Rainbow Serpent The Aboriginal people believe the Rainbow Serpent is the creator of all things. During the Dreamtime the Rainbow Serpent created the Aboriginal people, birds, trees, hills and mountains. During sacred ceremonies the Aboriginal Elders would tell stories to the tribe about the Rainbow Serpent and its power. The Rainbow Serpent was also called upon in times of need to protect the Aboriginal people from predators. A Rainbow Serpent Story The Rainbow serpent came from Northern Australia in an era when this country was in its dreaming origins. As it travelled throughout the length and breadth of this country, it created as it writhed over this land the mountainous geographic locations by pushing the land into many ranges and isolated areas. The Great Dividing Range is said to be a creation of the Rainbow Serpent’s movements. Throughout its journey over and under the land it created rivers, valleys, lakes, and was also careful to leave many areas flat, while shaping various land gradients for future water run-off. After it was satisfied with what it did, it came to a point in Central Australia where it ceased to create any more geographical land forms. From its inside, spirit people came out and began to move all over this country to create many different lifestyles, speak many languages and thus to evolve as different but similar entities in own allotted Dreamtime homelands. Mother Earth My young and beautiful mother who brought me into the world has guided and given me incentive – which path to take on my way. My elder and beautiful mother who holds my feet to her breast shows me all parts of nature which alone she knows best. My young mother with the beauty of the bright golden sunray showed me the feeling and love of nature when I was young at play. My elder and beautiful mother with her ochre colour of red that flows, one day she will make body, when? No one knows. My young and beautiful mother will pine and cry for me. My elder and beautiful mother will take my body to her breast with thee. But she knows she can’t hold my spirit, for in the Dreamtime It will for ever be! (From a Land Rights Poster, c. 1973, author unknown) THE LAND For Aborigines the land is sacred Places on earth share in the sacredness of the Dreaming since these places were formed by the journeys of the Ancestor Beings Mountains are seen as places where the Ancestor Being looked over the land and dry claypans are places where they camped Some Ancestor Beings are said to have gone up to the stars as final resting place For Aborigines the land is not dead but alive with power and the Ancestors who live in it The land belongs to ancestors and while land lives so do the ancestors The land is the centre of Aboriginal spirituality Uluru A sacred site to the Anangu people of Central Australia Aborigines believe that Uluru is hollow below ground, and that there is an energy source which they call 'Tjukurpa' or the Dreamtime. The Anangu know that the area around Uluru is inhabited by dozens of ancestral beings whose activities are recorded at many separate sites. At each site, the events that took place can be recounted, whether those events were of significance or whether the ancestral being just rested at a certain place before going on. “To understand our law, our culture and our relationship to the physical and spiritual world, you must begin with land. Everything about aboriginal society is inextricably woven with, and connected to, land. Culture is the land, the land and spirituality of aboriginal people, our cultural beliefs or reason for existence is the land. You take that away and you take away our reason for existence. We have grown that land up. We are dancing, singing, and painting for the land. We are celebrating the land. Removed from our lands, we are literally removed from ourselves.” Mick Dodson Mick Dodson Mick Dodson is one of Australia's most vocal and well-known advocates for Aboriginal rights, and has been appointed to the first Indigenous Chair at the Australian National University. He was Australia's first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. Now a professor, his job will be to develop and coordinate indigenous scholarship and research. One of his challenges will be to try and break down what he regards as snobbish attitudes at universities. In January 2009 he was named Australian of the Year. Aboriginal people, when speaking in English of the connection with land, often refer to land as "country". Anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose has described 'country' in this way: Deborah Bird Rose is an anthropologist who works at the Australian National University in Canberra. She has commented on Aboriginal people and the land "People talk about country in the same way that they would talk about a person: they speak to country, sing to country, visit country, worry about country, feel sorry for country, and long for country. People say that country knows, hears, smells, takes notice, takes care, is sorry or happy. …country is a living entity with a yesterday, today and tomorrow, with a consciousness, and a will toward life. Because of this richness, country is home, and peace; nourishment for body, mind, and spirit; heart's ease." Deborah Bird Rose LAND USE AND OWNERSHIP Ownership of land means responsibility to care for it and nurture it as a sacred trust to be preserved and passed on in a timeless cycle Land not only has an economic use (food, water and work) but also a ritual or spiritual use Aborigines therefore have a ‘ritual estate’ or a heartland of a local group – ‘My country’ My country contain sites of spiritual significance or sacred sites and it is a lifetime’s work to know the stories of ‘my country’ together with the rights and responsibilities an individual has for it Sometimes people have to travel over or use other people’s ritual estate (searching for food or water) and great care is needed not to break the Law of these people LAND USE AND OWNERSHIP Other people’s sacred sites must not be approached The stories of another country must not be talked about by someone travelling through or using it Punishments were traditionally very severe if the Law of a country was broken A person is safest in their own country where the rights and responsibilities are known by everyone and respected Ownership of land is based on division and distribution of ritual responsibility for land and sacred sites and not on the Western notion of owning, using or occupying land Traditionally Aborigines are very familiar with their country and are rarely lost in it Mervyn Rubuntja - Water Snake Dreaming This painting is by Mervyn Rubuntja, the son of the well known Arrernte artist Wenten Rubuntja. This is an older work by Mervyn, from 1989, and was painted in the Larapinta Valley south of Hermannsburg. It tells of the rainbow snake (Gunina) which came from Palm Valley to Boggy Hole (places near Hermannsburg). The snake still lives in Boggy Hole and "if you go swimming in Boggy Hole now, policeman find you dead". This large work has been beautifully painted, with fine dots and careful use of traditional symbols. Acrylic on canvas 1989 Bessie Nakamarra Sims Born: c.1932 Location: Yuendumu, Tanami Desert Language: Warlpiri Medium: acrylic paint on canvas and linen Bessie Sims is one of the strongest supporters of Warlukurlangu Artists. She has painted since the mid 1980s and has consistently exhibited nationally and internationally in group shows. Her husband is Paddy Japaljarri Sims with whom she occasionally collaborates on larger works. The main dreamings in her work are Ngarlajiyi (Small Yam), Janganpa (Possum), Pamapardu (Flying Ant), Karntajarra (Two Women), Yarla (Bush Potato) and Mukaki (Bush Plum). Darby Ross - Yankirri Jukurrpa Born c. 1910 This is the most recent work that Darby has done (2001). It depicts Ngarlikurlangu (north of Yuendumu). As a Jampijinpa man, Darby is kirda (owner) of this Yankirri (Emu) Jukurrpa. He has depicted the sacred place of Ngarlikirlangu and the woliya (footprints) of the emu as it travels the Jukurrpa. Paddy Japaljarri Sims Paddy is a Warlpiri speaker who was born some time around 1917 at Kunajarrayi (Mt Nicker) west of Yuendumu, in the Northern Territory. He is one of the truly outstanding artists of Yuendumu who has been an influential figure in the development of art in the region. He has a distinctive style and paints a number of dreamings (Jukurrpa) connected with his country: Witi (Ceremonial Pole), Yanjirlypiri (Star), Yiwarra (Milky Way), Munga (Night), Ngarlkirdi (Witchetty Grub), Liwirringki (Burrowing Skink), Jungunypa (Marsupial Mouse), Mala (Rufous Hare Wallaby), Wakulyarri (Rock Wallaby), Warlu (Fire), Wanakiji (Bush Tomato), Ngalyipi (Snake Vine) and Jurlpu (Bird). Art of the Western Desert Aborigines of the Western Desert traditionally made sand paintings using coloured soils. The most characteristic quality of these works was the use of dots and cirlces. Today Aborigines use acrylic paint to construct these works. ART, STORIES, SONGS, SACRED OBJECTS AND CEREMONIES All have important place in Aboriginal life and Dreaming - not separate from or additional to beliefs Art important aspect of religion and expression of belief in creation and working of universe – art connects Aboriginal people with Dreaming Rock paintings for example are thought to have been left behind by Ancestor Beings Art connects people with ‘my country’ and is often in form of a map Some Aboriginal art (e.g. desert regions) is: abstract, full of mythological symbolism such as circles and lines which contain meanings Other art (e.g. Kimberley, Arnhem Land, Cape York) is more representational Modern example of desert art Symbols used in desert art Traditional - 1912 ART, STORIES, SONGS, SACRED OBJECTS AND CEREMONIES Despite regional differences all Aboriginal art has strong design and harmonic features Some art was very secret while other art was less secret – difference between sacred/secret & public What appears to be abstract is really symbolic No written literature in tradition Aboriginal society but large amount of oral stories/tradition passed on from generation to generation Stories have many versions and layers, e.g. children’s, women’s & male versions Secret/sacred stories associated with particular sites and ceremonies, e.g. initiation ART, STORIES, SONGS, SACRED OBJECTS AND CEREMONIES Stories record travels/activities of Dreaming Ancestors – closely related to shape of land As living people move over land stories give them knowledge of land, e.g. waterholes Song-cycles are used to recall tracks of Ancestral Beings – each song recalls activities of a Being at a site and become part of ritual at sites Songs often accompanied by dancing People who know and perform songs gain status and respect Groups are responsible for their songs An Uluru Story In the creation period, Tatji, the small Red Lizard, who lived on the mulgi flats, came to Uluru. He threw his kali, a curved throwing stick, and it became embedded in the surface. He used his hands to scoop it out in his efforts to retrieve his kali, leaving a series of bowlshaped hollows. Unable to recover his kali, he finally died in this cave. His implements and bodily remains survive as large boulders on the cave floor. The Bell-Bird brothers, were stalking an emu. The disturbed animal ran northward toward Uluru. Two bluetongued lizard men, Mita and Lungkata, killed it, and butchered it with a stone axe. Large joints of meat survive as a fractured slab of sandstone. When the Bell-Bird brothers arrived, the lizards handed them a skinny portion of emu, claiming there was nothing else. In revenge, the Bell-Bird brothers set fire to the Lizard's shelter. The men tried to escape by climbing the rock face, but fell and were burned to death. The gray lichen on the rock face is the smoke from the fire and the lizard men are two half-buried boulders. In several caves in Uluru, rock represents many stories of the Dreamtime. The paintings are regularly renewed, with layer upon layer of paint, dating back many thousands of years. SACRED OBJECTS Sacred objects are used to give knowledge and power These include: stones with markings, carved boards and poles Some marked rocks are only brought out on special occasions and are thought to have been left by the Ancestral Beings Here is a picture of a sacred pole from Arnhem Land ART, STORIES, SONGS, SACRED OBJECTS AND CEREMONIES Ceremonies in two groups: Rites of passage where people move life stages Periodic ceremonies performed at various times for a variety of reasons Reasons for ceremonies include: Enjoyment Promoting health and well-being of whole group Ceremonies can be combination of public and sacred/secret rituals Sacred/secret are restricted to initiated – noninitiated and non-Aboriginals cannot attend CEREMONIES - INITIATION Initiation for boys and girls is most important event in traditional Aboriginal life Initiation is part of the perpetuation and celebration of the Dreaming Initiation can symbolise death of child and birth of adult where new roles in tribe are given Initiation admits boy/girl to sacred/secret life Preceded by period of seclusion away from larger group where sacred/secret rituals take place and knowledge given On return new status is celebrated as man or woman and education continues under supervision of elders Education continues throughout life as further knowledge of land, people and Law Initiation often includes face or body painting, piercing or cutting as well as music and dancing CEREMONIES – DEATH AND BURIAL Aborigines see death not as end of life but last ceremony in present life Spirit of dead return to Dreaming Places they came from as part of eternal transition of life-force of Dreaming Burial grounds and spirits of dead are greatly feared – names of dead cannot be spoken (this has been acknowledged by media in recent times and permission must be sought to say names) Dead must be buried in own country and spirits properly sung to rest (or in caves, rock platforms, trees, hollow logs, special houses for the dead – sometimes cremated) Burial ceremonies vary widely from place to place and in accordance with status of person Ceremonies can continue for months or even years Pukumani Poles Mortuary Ceremony Tiwi Islands This ceremony ensures that the spirit of the dead person goes from the living world into the spirit world. The Pukumani is a public ceremony and provides a forum for artistic expression through song, dance, sculpture and body painting. It occurs approximately six months after the deceased has been buried. The Tiwi believe that the dead person's existence in the living world is not finished until the completion of the ceremony. The final Pukumani is the climax of a series of ceremonies that traditionally continued for many months after the burial of the dead. There is usually one iliana (minor ceremony) at the time of death and then many months later the final Pukumani. The ceremony culminates in the erection of monumental carved and decorated Pukumani poles which take many months to prepare and are impressive gifts to placate the spirit of the dead. These poles are placed around the burial site during the ceremony. They symbolise the status and prestige of the deceased. Participants in the ceremony are painted with natural ochres in many different designs, transforming the dancers and providing protection against recognition by the spirit of the deceased. A series of dances (yoi) is performed. Aside from creative and illustrative performances there are those that certain kin such as the mother, father, sibling and widow - must dance. When all is concluded and the last wailing notes of the amburu (death song) have died away, the grave is deserted and the burial poles allowed to decay. THE LAW Aboriginal Law encoded in each group’s Dreaming Ancestor Being decided rights and responsibilities and the behaviour of all things they made Human organisation – relationships, ritual responsibilities to land and rights over it – are encoded in Dreamtime stories and handed on from generation to generation in dance, music, art and ceremonies Gatherings of Aborigines were to settle disputes Today Aboriginal outstations still use what is called ‘Aboriginal customary law’ to settle disputes and punish offences and this is recognised by the Australian legal system SETTLEMENT White settlement usually resulted in death of Aborigines or disruption to lifestyle and economy Settler wanted water, good land, shelter and access to food like fish – all of which were important to Aborigines as well White settler altered landscape by clearing trees and building fences – this caused conflict As settlement continued Aboriginal numbers decreased and way of life destroyed Survivors lived within or on fringes of European communities Some Aborigines came freely because whites gave them food and tobacco but others were rounded up by police and forced in missions or government settlements Aborigines were often rounded up like animals and driven off their land to settlements by the police. This picture of a round up was painted in Western Australia in the 1840s. Aborigines rounded up and placed in chains are paraded for the camera in early 20th century Chained Aborgines Victoria Late 19th Century SETTLEMENT Some Aborigines became attached to cattle and sheep stations and worked for rations/clothing Aborigines became at mercy of missions, government settlements or pastoralists Some had active policy of destroying Aboriginal culture such as language, art and ceremonies and they would not allow relatives to visit Children were often separated from parents Some tried to work within Aboriginal culture adapting their teachings to local conditions Some pastoralist allowed big gatherings of Aborigines at sacred sites but most did not In all states the movement of Aboriginal people was harshly controlled SETTLEMENT In other places contact with non-Aboriginal communities had significant impact: Gold rush areas – violence and drunkenness Sealers stole women and killed men and children Pearlers stole young boys Missions and settlement compacted Aborigines together not allowing them to spread out – this meant ceremonies could not be carried out Extinction or near extinction undermined whole culture – lack of numbers meant complex religious and cultural practices were not maintained Aboriginal Law and authority and relationship with land was undermined or destroyed Land was lost to more powerful white settlers LAND RIGHTS Driving Aborigines off land did more than deprive them of property Also deprived them of independence, culture, spiritual world 1970s – ‘land rights’ was termed used for what had been a source of protest for many years – that is, protest against loss of Aboriginal land 1888 Australian centenary celebrations were boycotted by Aborigines – no one noticed 1938 sesquicentenary was declared a Day of Mourning for Aboriginal people and protests were held in Sydney 5 days later delegation met with PM to protest about treatment of Aborigines – esp. housing, education, working conditions, welfare and land purchases Aboriginal Day of Mourning declared by Aboriginal protest groups on Australia Day, 1938 Australia Day Protest, 1988 LAND RIGHTS But not until 1967 that referendum overwhelmingly voted YES that: Aboriginals counted in national census Commonwealth have power to make laws for them 1963 – Yirrkala people of NT presented bark petition for land to Commonwealth Govt. Gained momentum – Gurindji people living and working on Wave Hill Station went on strike to press their claim about adequate wages for work 1970 – bicentenary of Cook’s arrival at Botany Bay – Aboriginal protest for land rights 1972 – tent embassy appeared on lawns of Parliament House Canberra – Aboriginal Embassy or Tent Embassy Aboriginal flag flown for the first time here Yirrkala Bark Petitions - 1963 View text of Yirrkala and read background at: http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/places/cth/cth15.htm Wave Hill Strike - 1966 In August 1966 Gurindji people led by Vincent Lingiari at Wave Hill cattle station went on a nine year strike demanding better wages and conditions and a return of some of their traditional lands. Wave Hill Station was owned by an Englishman, Lord Vestey. The demand was rejected but the Gurindji continued to camp on their traditional country establishing a settlement at Daguragu - they broke the white man's law but obeyed their own. The campaign was taken up by supporters in Australia's cities and eventually the Gurindji won title to part of their land. The Ration Wave Hill Vincent Lingiari 1966 The Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra has maintained a constant presence since 1972. It aims to keep Aboriginal issues like Land Rights alive and to embarrass the Government. A fire burns continuously at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra to show that this is a meeting place for all Aborigines on what was once Aboriginal land. Site of Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Canberra in its early days following 1972. Media reporters and visitors from all over the world saw the protest just across the road from Parliament House. Despite attempts to evict the protestors it has always been rebuilt. Many Aborigines from around Australia support the protest by working at the Embassy. In 1995 the Australian Heritage Commission recognised the Tent Embassy as a site of special cultural significance and it was entered on the Register of the National Estate – list of natural and cultural heritage places. LAND RIGHTS Land Rights: claims by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to repossession and compensation for White use of their lands and sacred sites Native Title: Name given by High Court of Australia to indigenous property rights recognised by the courts as handed down in the Mabo Decision (3 June, 1992) Land Rights Acts in most Australian states: NT in 1976; SA in 1981; NSW in 1983; Qld in 1991 Limited land rights in WA but in NT 42% of land is Aboriginal land under inalienable freehold title Aboriginal Elder Vincent Lingiari and Prime Minister Gough Whitlam at the hand over of Daguragu to the Gurindji in NT, 1975. This was one of the first successful land rights claims to be settled. Whitlam symbolically places the earth in Lingiari’s hand to show Aboriginal ownership of the Land. NATIVE TITLE 1992 – High Court of Australia ruled in what was called ‘The Mabo Decision’ that native title to land existed in 1788 Justice Brennan in 1992 overthrew terra nullius arguing: “The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary laws in this country .. The common law of this country would perpetuate injustice if it were to continue to embrace the enlarged notion of terra nullius and to persists in characterising the indigenous inhabitants of the Australian colonies as people too low in the scale of social organisation to be acknowledged as possessing rights and interests in land” NATIVE TITLE Terra nullius meant that Australia was ‘empty (or nothing) earth’ – land without ordered society that could be called civilisation Terra nullius had allowed Europeans to occupy land and ignore Aboriginal claims and culture because they said nothing existed here The High Court of Australia overturned this argument and said that native title existed where traditional customs and laws applied Freehold land (private ownership) was not part of the land where native title existed Eddie Mabo 1936-1992 A Torres Strait Islander who believed that white laws about land ownership were wrong and who fought to change them. He fought a ten year battle through the courts which culminated in the Mabo Decision of 1992 by the High Court of Australia. Eddie Mabo was able to prove in court that he and his family had ownership of their land on Murray Island in the Torres Strait. This implication of this decision was that terra nullius was overthrown and the argument that there was no native title was defeated. This had implications for all Australians. NATIVE TITLE ACT, 1993 1993 – Native Title Act passed through Commonwealth Parliament. This Act: Set up a National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) to help mediate claims - http://www.nntt.gov.au Provided for Indigenous Land Fund to assist those whose native title had been extinguished Protected native title by requiring that traditional owners be consulted in advance if government were considering granting leases to mining companies or others Since 1993 Native Title and agreements on land use have been reached THE WIK DECISION, 1996 The Howard Government, elected in March, 1996, had policy of amending the Native Title Act to make it more ‘workable’ In December, 1996, the High Court of Australia handed down the Wik Decision which said that native title could co-exist with other rights on land held under a pastoral lease – court said each lease must be determined on its own merits PM John Howard introduced his ‘Ten Point Plan’ to put the Wik Decision into action – among these points was severe reduction of right of Aborigines to negotiate 1998 – Native Title Amendment Act passed Commonwealth Parliament – empowered states and territories to legislate their own native title methods WHAT DOES WIK DECISION MEAN? The Wik Decision is a decision of the High Court of Australia in December 1996, following a case brought by the Wik people of Cape York in North Queensland. It concerns only their right of access to the land held under pastoral leases (ie Crown land used - but not owned - by pastoralists for cattle grazing). The court decided (4 judges to 3) that indigenous people who can prove a connection to the land may have rights to hold ceremonies and perform other traditional activities - as long as they don't interfere with the pastoralists' legitimate activities. In other words, pastoral leases do not automatically give exclusive possession to the pastoralist, and therefore do not necessarily extinguish native title. This had been a major assumption upon which the Commonwealth Native Title Act had first been drafted. The Wik Decision holds that native title might co-exist on pastoral leases, but the rights of pastoral leaseholders prevail over any inconsistent rights that native title holders might have. FRANCES BELLE PARKER Frances (born 1982) is a young Aboriginal artist who tries to Integrate her aboriginality and Christian spirituality In 2000 Frances won the prestigious Blake Prize for Religious Art with her painting ‘The Journey’ The Journey A painting by Frances Belle Parker won the Blake Prize for Religious Art in 2000. What is the message of the painting? Reconcile Sacred Soul Share with me Unity A Case Study Balgo Catholic Parish Western Australia Band at Catholic Church at Balgo in Western Australia Madonna and Child by Aboriginal artist Christ in the Desert A series of Aboriginal art works showing the combination of Christian and Aboriginal spirituality Artist unknown. This banner, hanging in the Jesuits' Kutjungka Catholic Church in Wirramanu, Western Australia, is an example of Aboriginal artists' combination of Christian elements and Aboriginal design. Artist unknown. In this depiction of Pentecost, twelve tongues of flame hover above the crescent shapes that represent the apostles sitting. Artist unknown. The Church at Wirramanu is steward of a number of paintings that reflect meldings of Aboriginal design and Christian elements. “Nativity” The central figure represents the infant Jesus; crescents represent the seated figures of Mary and Joseph. Artist unknown. This infant Jesus lies in a coolomon, a hollowed-out wooden vessel used as a crib by Aborigines. Crescent shapes represent figures, more accurately, the impression seated figures would leave on the ground.