The Unification of Italy and Germany

advertisement

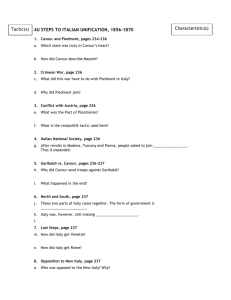

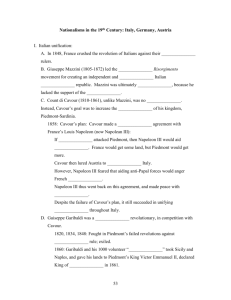

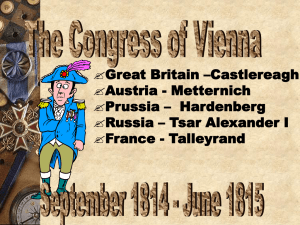

NATIONAL UNIFICATION IN ITALY AND GERMANY In both Italy and Germany, nationalism first emerged as a democratic movement inspired by Rousseau. In both Italy and Germany, after 1849 many nationalists looked to their most powerful monarchs for leadership. 1859/60: Unification of Italy (except for Rome and Venice) under the leadership of Piedmont and Cavour. 1864: Danish War (Prussia under Bismarck allies with Austria to conquer Schleswig-Holstein). 1866: Prussia defeats Austria in Seven Weeks War; Italy annexes Venice. 1870/71: Franco-Prussian War leads to foundation of the German Empire; Italy annexes Rome. Italy after the Congress of Vienna The muscle and the brains of the Risorgimento: Garibaldi first meets Giuseppe Mazzini in 1833 MAZZINI’S VISION OF ‘THE NATION’ WAS DEMOCRATIC & EGALITARIAN “Without Country you have neither name, token, voice, nor rights, no admission as brothers into the fellowship of the Peoples…. Soldiers without a banner, Israelites among the nations, you will find neither faith nor protection. Do not beguile yourselves with the hope of emancipation from unjust social conditions if you do not first conquer a Country for yourselves; where there is no Country there is no common agreement to which you can appeal; the egoism of self-interest rules alone. Do not be led away by the idea of improving your material conditions without first solving the national question. You cannot do it…. Votes, education, the right to work are the three main pillars of the nation; do not rest until our hands have solidly erected them.” “The Republic of Rome Rings the Bell of Liberty” (1849) Garibaldini in the Republic of Rome, July 1849 French troops enter Rome to restore Papal rule, April 30, 1849, on the orders of President Louis Napoleon Count Camillo di Cavour, Prime Minister of Piedmont Emperor Napoleon III THE FRANCO-PIEDMONTESE ALLIANCE, concluded at Plombières in July 1858 (see Western Heritage, 665-66) Napoleon III promised to support Piedmont in a war to expel the Austrians from Italy, but only if it was a “nonrevolutionary” war. Piedmont would cede Nice and Savoy to France in exchange for military aid against Austria. Piedmont should annex northern Italy, but the Pope and King of Naples would be left alone. The Pope would be invited to serve as president of a loose Italian Confederation. “Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino, 24 June 1859” (the Franco-Sardinian army lost 17,000 men killed; the Austrians, 22,000) Garibaldi in 1860 (chromolithograph): He appealed for “Red Shirt” volunteers to carry on the crusade for national unification The Embarcation of the Thousand, Genoa, May 1860 The Liberation of Palermo, May 27, 1860 “The Man in Possession. Victor Emmanuel: ‘I wonder when he will open the door.’” “The Right Leg in the Boot at Last.” Garibaldi: “If it won’t go on, Sire, try a little more powder!” (London, 1860) ENDURING DIVISIONS WITHIN “UNIFIED” ITALY 1. The Vatican excommunicated any Catholic who accepted government office. 2. Italy was unified through a plebiscite, endorsing annexation by Piedmont, not a constitutional convention. 3. Only about 2% of the population could vote. 4. Piedmont’s Free Trade policy ruined the less efficient manufacturers of the South, so the economic gap between North & South widened after 1860. 5. Most government officials in Naples and Sicily came from the North. The German Confederation of 1815-1866 “Is That Where the Problem Lies?” (1859): Germany’s Nationalist Association sees the path blocked by the princely houses Prussia’s King William I appointed Otto von Bismarck as prime minister in 1862 BISMARCK’S VIEW OF HISTORY SPEECH TO THE PRUSSIAN HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, September 30, 1862: “Germany does not look to Prussia's liberalism but to its power. Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden may indulge liberal impulses, but nobody will cast them in Prussia's role for that reason. Prussia must gather its forces and maintain them for the favorable moment, which has already been missed several times. The borders established for Prussia at the Vienna Congress are not favorable for the healthy life of the state. The great issues of the day are not decided through speeches and majority resolutions--that was the great error of 1848 and 1849--but through blood and iron.” “In the Circus”-- Bismarck tames the Progressives (January 1864) Schleswig-Holstein on the eve of the war of 1864 The conquest of Schleswig-Holstein by Prussia & Austria, 1864 THE SEVEN WEEKS’ WAR, 1866: Three Prussian armies converged swiftly in Bohemia Christian Sell, “The Battle of Königgratz,” July 3, 1866 (225,000 Prussians rout 215,000 Austrians) Victory Parade, Berlin, September 1866 THE INDEMNITY BILL (passed by a vote of 230 : 75 in the Prussian House of Representatives on September 3, 1866) ARTICLE 1. The government is granted indemnity for all administrative acts undertaken since the beginning of the year 1862 without a legally established state budget…. ARTICLE 2. The government is authorized to expend up to 154 million Taler on administration for the year 1866. “The German Pasture,” Kladderadatsch, 31 March 1867: Germania tells Bismarck to “Protect my sheep” from Napoleon III THE GERMAN INVASION OF FRANCE, AUGUST-OCTOBER 1870 German artillery park at Sedan, September 1870: The new Krupp breech-loading steel cannon Ernest Meissonier, “The Siege of Paris” (1870-1884) William I hailed as German Kaiser, Versailles, January 18, 1871 John Trumbull, “The Declaration of Independence” (1819) The German victory parade down the Champs Elysées, March 1, 1871 The borders of the German Empire, 1871-1918 BISMARCK’S IDEAL FOR THE GERMAN EMPIRE (1871-1918): “Monarchic Constitutionalism” A new Reichstag was elected by universal and equal manhood suffrage. But the Chancellor served at the pleasure of the Kaiser, and there was no civilian control of the military. No measure could become law unless approved by an upper house of delegates appointed by the state governments (creating a disguised royal veto). Important powers were reserved to the states (Prussia, Bavaria, etc.), e.g., the right to impose direct taxes on property and income. Prussia and most other state governments retained a 3-class suffrage where the weight of your vote depended on how much you paid in taxes.