Aspasia and Aristotle: The Parents of Rhetoric???

advertisement

Aspasia and Aristotle:

The First Lady and the Father of Greek Rhetoric

November 6, 2006

Grace Bernhardt and Shreelina Ghosh

Aspasia’s Background

Non-Athenian Greek female

From Miletus, one of the Greek colonies in Ionia

“it is logical to assume that she came in contact

with early philosophical thought in some form”

(J&O, 10)

Arrived in Athens in mid-440s B.C.E.

Sources: Aspasia: Rhetoric, Gender, and Colonial Ideology by Susan Jarratt and Rory Ong

Aspasia, pages 56-66 of Bizzell and Herzberg

Aspasia’s Background

Companion of Pericles, the democratic

leader of Athens

As foreigner, forbidden from marrying Pericles

Jarrat and Ong claim she did not fit categories

for Athenian women of wives, concubines,

hetaerae, or prostitutes; often mislabeled a

mistress or courtesan

Did she run a house of prostitution? Was she

a courtesan or hetaera? Does it matter?

Aspasia’s Background

Teacher of Rhetoric

Helped Pericles compose Funeral Oration

Taught Socrates (?)

Developed the Socratic method (?)

Kennedy makes no reference to Aspasia’s influence when

describing the Funeral Oration attributed to Pericles (204)

“It is easy to imagine that such an indirect method

originated with a woman who was legally powerless, in a

compromised and vulnerable position, but who attempted

to advise and influence men of great power.” (B&H, 59)

None of her texts have survived

Aspasia in Classical Sources

Several paragraphs of narrative in Plutarch’s

life of Pericles

Oration attributed to her in Plato’s dialogue

Menexenus

Allusions to Aspasia also made by four of

Socrates’ pupils

In works by Athenaeus

Dialogue attributed to her by Xenophon

Jarratt and Ong’s Purposes

“To reconstruct Aspasia as a rhetorician of

fifth-century B.C.E.” (9)

Part of a larger goal of “recovering women in

the history of rhetoric” (10)

To argue that Aspasia “marks the intersection

of discourses on gender and colonialism,

production and reproduction, rhetoric and

philosophy” (J&O, 10)

Bizzell and Herzberg’s Purposes

To explore the complexity of the role of

women in ancient Greece

To explore and present historical texts which

reference Aspasia

To question how Aspasia, a woman with no

surviving texts, can be included in a history of

rhetoric (while acknowledging that no texts of

Socrates exist either!)

Jarratt and Ong’s Motivating Questions

“Did Aspasia exist?”

“If so, can she be known?”

“And then, is that knowledge communicable?”

(9)

Bizzell and Herzberg’s Motivating Questions

How can we explain the existence of a

woman such as Aspasia in a Greek society

that limited women to the home?

Was Aspasia a hetaera when Pericles met

her?

How plausible is it that a woman could have

possessed the skills that Aspasia did?

Jarratt and Ong’s Methods

A review of the classic sources

An overview of the current commentary

An undertaking of interpretive histiographical

tasks

Bizzell and Herzberg’s Methods

Presentation and analysis of historical texts

referencing Aspasia

Aspasia in Plato’s Menexenus

Dialogue between Socrates and Menexenus

Socrates acknowledges that Aspasia was his

teacher and that she composed funeral

orations

The oration attributed to Aspasia is

“exaggerated in style, with just the sorts of

embellishments that Socrates elsewhere

condemns, and full of historical errors that

create an absurdly positive view of Athens.”

(B&H, 58)

Interpreting Plato’s Representation

Bloedow sees Aspasia as representative of

rhetoric and democracy (J&O, 17)

Jarratt and Ong look at Aspasia as “at the

intersection of the axes of gender and

colonialism” (J&O, 18)

Gender in Menexenus

“Reading the literary text against the social

text, we find Plato giving voice to a woman at

a time when women were mostly denied

public voice, and fixed most effectively in the

role of reproduction.” (J&O, 18)

On one level, Plato seems to expand

conception of female

Closer reading shows reversal

Gender in Menexenus

Plato’s attribution of epitaphios to a female

author emphasizes the purpose of women: to

reproduce warriors (J&O, 18)

Autochthony – the conception that men were

born directly from the soil of Athens

Aspasia’s oration talks at length about

autochthony—Plato “forc[es] her to testify to

her own devaluation as a female.” (B&H, 58)

Gender in Menexenus

Jarratt and Ong contend that Plato’s choice

to include Aspasia as author of oration serves

to downplay woman’s power and creativity

Bizzell and Herzberg present alternative

view— “Other scholars, however propose

that Socrates really did admire Aspasia and

that Plato is doing no more than poking fun at

this admiration.” (58-59)

Colonial Ideology in Menexenus

Plato emphasizes autochthony

“True mother” for Athenians (whole) and

“stepmother” for others (fractured)

Ideology hides unequal power relations

between men and women and the power of

cultural dominance

Colonial Ideology in Menexenus

“Defining the norm through a polar opposition

wipes out difference within each pole,

differences that, in this case, expose the

relations of production in an imperialist

economy.” (J&O, 21)

Aspasia represents the “stranger,”

“sojourner,” and “woman” all at once

Questions to Ponder

Bizzell and Herzberg conclude that

If indeed she did teach Socrates the so-called Socratic

method, her contribution to the history of both philosophy and

rhetoric is far-ranging. At the very least, recognizing her

activity here erects a monument to the rhetorical labors of

Aspasia and other classical women and marks the spot where

a more substantial edifice may be built if the search for textual

remains succeeds. (59)

Is it necessary for a rhetorician or philosopher to contribute a

“method” or theory in order to be included in history?

Are textual remains necessary for understanding a person’s role

in history?

How might we piece together the contributions of women to

Greek rhetoric in light of the fact that few, if any, artifacts have

survived?

Pandora’s Box: The Roles of Women in

Ancient Greece

Lecturer Ellen B.

Reeder, curator of the

Walters Art Gallery in

Baltimore

Fall of 1995 exhibit with

accompanying

catalogue

Reviews the lives of

Greek women and their

portrayal in art (mostly

pottery)

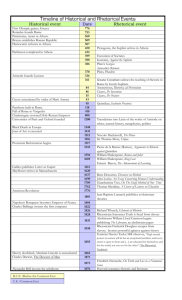

Aristotle

384-322 B.C.E.

Born to Greek parents in the Macedonian

town of Stagira around the time Plato opened

the Academy in Athens

Entered Academy at 17 years old

Stayed on as teacher, leaving 20 years later

upon Plato’s death

Sources: Aristotle, pages 169-240 of Bizzell and Herzberg,

Chapter 9: Rhetoric in Greece and Rome, Kennedy

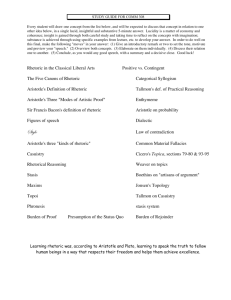

Aristotle’s Rhetorical Theory

Artistic proofs

Logos

Enthymeme

Maxim

Example

Pathos

Ethos

Inartistic proofs

Inventio

Topoi

Special group

Common group

Stasis

Conjectural

Definitional

Quantitative

Translative

Aristotle’s Three Types of Speeches

Forensic speeches

Deliberative speeches

Epideictic or ceremonial speeches

The Five Canons

Invention

Arrangement

Style

Memory

Delivery

Aristotle’s Rhetoric

Never published in Aristotle’s lifetime

Most likely not intended for publication

Began as notes for rhetoric classes in the

Academy

Divided into three books

“‘Published’ (hand-copied) for the first time by

Andronicus of Rhodes” around 83 B.C.E.

First printed edition published in 1475 B.C.E. by

George of Trebizond

Three Books of RHETORIC

Book One: Definition and

Kinds of Rhetoric

Book Two: Kinds of

Proofs

Book Three: Delivery

Questions for Discussion

Rhetoric is a productive knowledge in that it does "

'produce' persuasion, speeches, and texts'; but as a

discipline concerned with " 'seeing' the available

means of persuasion (thus not necessarily of using

them),' rhetoric also maintains a theoretical aspect.

Janet Atwill’s review of Classical Rhetoric : Its Christian and Secular Tradition (U

of North Carolina P, 1980) by George A. Kennedy

Discussion Prompt : Practical, Theoretical and

Productive aspects of Rhetoric

Epistēmē … Praxis … Poiēsis

Aristotle’s eudaimonia

Eudaimonia translates as “happiness” or “the

good life”

For Aristotle, distribution of eudaimonia is not

equal

Aristotle wrestles over whether eudaimonia is

an activity or a state

Sources: Aristotle and the Boundaries of the Good Life and

Aristotle’s Rhetoric and the Theory/Practice Binary by Janet M. Atwill

Aristotle’s Taxonomy of Knowledge

Theoretical knowledge

Philosophy

Metaphysics, math, natural sciences

“Highest knowledge”

Actual knowledge that is identical with its object

Contemplation of the notion of an “end,” or telos

Pursued for no practical or utilitarian end

Aristotle’s Taxonomy of Knowledge

Practical knowledge

Study of ethics and politics

Directed toward the end of eudaimonia

Concerned with action and human behavior

Aristotle’s Taxonomy of Knowledge

Productive knowledge

Technai of architecture, navigation, medicine, and

rhetoric (?)

Concerned with the contingent or “what can be

otherwise” (173)

Implicated in social and economic exchange

Purposeful knowledge resistant to determinate ends

“Productive knowledge always remains in exchange

because its end is in the user as opposed to the

artistic construct.” (174)

Where does rhetoric fit?

Atwill argues that it is easy to exclude rhetoric

from theoretical knowledge because such

knowledge is concerned with day-to-day

functions of the state

It is harder to separate rhetoric from practical

knowledge because that means saying

rhetoric is distinct from ethics and an aim at

the good life (163)

Atwill’s Placement of Rhetoric

Atwill argues we should place rhetoric in

productive knowledge

“while it may seem strange to praise rhetoric

for failing either to consist of the highest

knowledge or to be driven by the end of the

“good life,” Aristotle’s greatest contribution to

rhetoric may have been his willingness to

allow it these two failures.” (164)

Theory/Practice Binary

Atwill states that the greatest barrier to

understanding productive knowledge is the

modern opposition of theory to practice (164)

This binary causes thought to have only two

forms—theoretical and practical

Binary then overshadows the triad and

productive knowledge gets left out

The Theory/Practice Binary

Gayatri Spivak writes in Explanation and

Culture: Marginalia {JAC 10.2 (1990)},

Aristotle’s techne is a “dynamic and

undecidable middle term” between theory and

practice.

Can writing bridge the binary?

Productive knowledge and rhetoric

Cope: art must be a form of productive

knowledge, but rhetoric is more of a practical

knowledge

Lobkowicz: notes that rhetoric is compared to

medicine as a kind of productive knowledge

Grimaldi: dismisses domain of productive

knowledge and puts rhetoric in theoretical

domain

Grimaldi and Rhetoric as

Theoretical Knowledge

Rhetoric’s relationship to philosophy

and ethics strongly indebted to

structural linguistics

Enthymeme is the “general method of

reasoning” and unites the three

rhetorical proofs of ethos, pathos and

logos.

Probabilities can be sufficiently rooted

to object reality to make an inference

from eikos.

Aristotle’s 28 koinoi topoi are ways in

which the mind naturally and readily

reasons.

Aristotle’s Application of Criteria

Aristotle’s definition of rhetoric emphasizes that

rhetorical knowledge is contingent on context,

time, and history (175)

“rhetoric must conform to the key criterion of

productive knowledge—the capacity to be

‘otherwise’” (175)

Aristotle’s triangular relationship between the

speaker, subject and audience makes clear

relationship of rhetoric and productive

knowledge with social exchange

Subjects of Productive Knowledge

Subjects of productive knowledge are

redefined by their use of techne and act of

social exchange

Techne can never be private property;

therefore, users and makers of techne

cannot be private, stable entities (185)

Subjects exist at point of competition

Productive knowledge crosses boundaries

of knowledge and subjectivity

Robyn’s Journal Comment

Anyway, I also think this quote contradicts

Kennedy's general belief that rhetoric is

conservative. I guess Atwill is not specifically talking

about rhetoric, but she is saying that rhetoric is a

techne and so it has these features, right? Anyway,

it seems she is saying the opposite of Kennedy: any

techne, including rhetoric, is not in the business of

"securing boundaries," but of "transgression and

renegotiation." Subjects of productive knowledge

are always crossing boundaries, always questioning.

Philosophy: Isocrates v. Aristotle

Isocrates: emphasizes the organizing power

of philosophy and its ability to help us

understand life; does not separate philosophy

from the art of discourse

Aristotle: philosophy is a higher order thinking

available when necessities of life are fulfilled;

places rhetoric in the domain of techne rather

than philosophy

Aristotle wins!

Philosophy has taken Aristotle’s definition

Aristotle’s taxonomy left room for art and

placed rhetoric in the domain of techne rather

than philosophy

Atwill states that “What is lost in the

taxonomy, however, is the sense of the art of

rhetoric as a valued mode of intervention into

existing conditions and a means for the

invention of new possibilities.” (189)

Ideal States: Plato v. Aristotle

Both are confronted with problem of how to

distribute rights, benefits and honors in a

state in which both order and value are

defined by class function. (178)

For Aristotle, distribution of eudaimonia is not

equal. Aristotle wrestles over whether

eudaimonia is an

activity or a state

Aristotle and Plato :

School of Athens by

Raphael

Ideal States: Plato v. Aristotle

Plato believes the philosopher/king rules in

ideal republic; compromise state is ruled by

laws

Aristotle’s ideal is aristocracy; compromise

state is a polity (mixed constitution that gives

political responsibility to the middle class)

Plato relies on technai to define hierarchy of

state

Aristotle relies on eudaimonia as basis for

state’s order

Analyzing Orators

Questions to Guide your Analysis

What appeals or strategies does the orator

use in their speech to convince their

audience?

What topoi does the orator use?

What type of speech is this, according to

Aristotle’s three types of speeches?

In what ways could the orator strengthen their

speech in Aristotle’s opinion?