Oxford Monitor of Forced Migration Vol. 3, No. 2

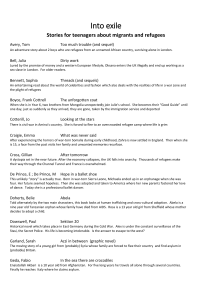

advertisement