Docx

advertisement

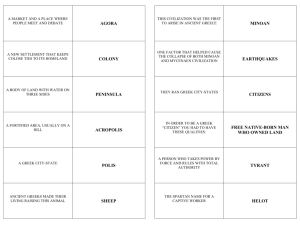

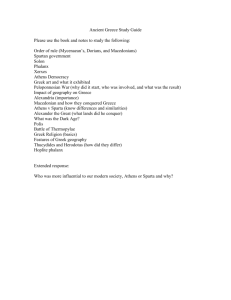

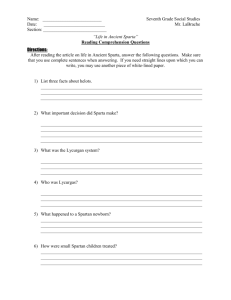

1 Archaic Greece and Classical Greece: the Introduction to Greek Warfare Introduction to the Lyric or Archaic Age of Greek History After the collapse of the Minoan and Mycenaean societies, Greece went through a period historians call the Dark Ages, circa 1100-800 B.C.E. Mainland Greece was invaded by the “Sea People” as the Ancient Egyptians called them. Greek historians call them the Dorians. These people were not literate, and the small vestiges of writing that had hitherto been evident in the previous ages was lost, and the Greek written language was gone. Two major enhancements did develop, which were the evolution of the polis or city-state and the colonization of Western Anatolia. Each of these city-states had a market place or agora, an acropolis or elevated area, and their own patron god or goddess. These poleis consisted of a town and the surrounding countryside where the people went daily to tend their crops or animals. As the populations grew, there was not enough arable land for farming, so the Greeks left for other islands, and what is now the Western coast of Turkey. These areas were similar in climate and soil to Greece, but thinly populated. Later on in the lyric or archaic age more migrations occurred to North Africa, Southern Italy, Southern France, Spain, and the Black Sea region. 2 Development of Various Forms of Governments for the Greek citystates in the Lyric or Archaic Age In the next age defined as the Lyric or Archaic age by scholars, more dramatic changes occurred. This period of Greek history lasted from circa 800-500 B.C.E. Various forms of governmental structures evolved over the centuries, and varied from city-state to city-state. Usually hereditary monarchies began in the ninth century B.C.E., where rule was by one man without absolute power. In the eighth century B.C.E. oligarchies or rule by the few were dominant. Rule by dictator or tyrant in the seventh century B.C.E., was where usurpers ruled without legal authority, although not all were oppressive. In the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. democracies surfaced as the common form of government, especially in Athens. Since more information is available to reconstruct the history of ancient Greece in Sparta and Athens, detailed information comparing and contrasting them is feasible. Comparison of the political structure of the city-states of Athens and Sparta: Athens Athens developed a prosperous trade and urban culture that ultimately led to its successful political structure called a democracy after a series of reforms. Solon (639-559 B.C.E.) is considered the founder of Athenian democracy. He formulated a constitution that reduced the powers of the 3 politically privileged nobles, and he created a new popular assembly open to all freemen. While this led to strife, it ultimately worked. Nearly six hundred nobles elected Solon archon, which was the chief magistrate of the polis.1 Cleisthenes in 510 B.C.E. made some significant changes and he is also known as the father of Athenian democracy. He used deme as the basis for democracy. The deme was a grouping of Athenians for governmental purposes, and eventually there were two hundred demes similar to modern ward or parish systems. He also enlarged the legislative authority of the Assembly to all male citizens who were born in Athens. This assembly met on Pnyx Hill, where the speaker’s podium faced a natural hillside amphitheater seating 18,000 persons. Once a year all male citizens were asked to vote on whether someone in the city ought to be banned as they might become a difficult or potentially dangerous politician. They needed not to have committed a crime, but were tending towards becoming a tyrant. All citizens who wanted to ban someone wrote his name on a piece of broken pottery or ostrakon, which is where we get the word ostracism. These ostrakons were deposited in the ballot box. Six thousands votes were needed to send a man into exile for ten years. As the assembly of all the citizens was usually too unwieldy, routine business was given to a council of five hundred representatives from the demes. This system attained full perfection in the Age of Pericles 461-429 B.C.E. A board of ten generals 1 America’s Senators are also referred to as Solons. 4 rose to positions roughly comparable to the British or American Cabinet, and they managed the army, navy, finances, and foreign affairs. Terms were one year, but eligible for reelection indefinitely. Pericles held the position of President or commander-in-chief for thirty years. He was really a benevolent dictator, but subject to approval of the Assembly. Pericles became the leader because he was the best orator. He and his mistress and then wife, Aspasia from Miletus, together built the Parthenon in honor of the goddess Athena, and beautified other parts of Athens with money from the Delian League. In the famous funeral oration by Pericles in 431 B.C.E. (probably co-authored by Aspasia), while honoring the fallen warriors of the ongoing Peloponnesian War, historians call Pericles’ speech a mighty tribute to democracy: “We are called a democracy for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while the law secures equal justice to all alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized. Neither is poverty a bar, but a man may benefit his country whatever be the obscurity of his condition.”2 Athens’ legal system was another clear sign of its democratic elements. Accusations were heard and judgments were given by enormous juries of from fifty to one thousand plus citizens. These juries were selected from the six thousand people who were chosen by random lot each year. Athens had no professional lawyers, and its citizens were discouraged from bringing 2 Herodotus 5 nuisance suits. If the accuser was not able to persuade at least 20% of the jury to vote to convict, the accuser had to pay a heavy fine. While there was no uniform penal code, respected laws had developed that were different from Mosaic or Babylonian laws. Greek law was not intended to carry out the will of either an omnipotent monarch or of a deity. Greek law was aimed entirely at improving the lot of humans. These ideas were passed on to the Romans, and ultimately to modern law codes. Novel ways of dealing with the punishment of crimes were evident for the Greeks. For example, in the case of accidental homicide, there was a prescribed route in Athens for the perpetrator to leave town. As long as the killer stuck to the route he was safe from revenge, and he had to stay out of town until the dead man’s relatives forgave him. For the most serious crimes, citizens had to drink poison from the hemlock bush. Death came quickly and without great suffering. Socrates’ demise will be discussed later. In Athenian democracy there was no separation of powers as the citizens directly participated in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. There were no career bureaucrats, and there was one vote per person regardless of one’s wealth. Majority ruled. Citizens spent hours every day arguing politics. No one was allowed to say anything considered actually dangerous to the state or insulting to the gods. Politics were therefore considered man’s natural occupation. Someone who did not interest himself in politics was both scorned and pitied. Pericles stated: “A man who shirked 6 responsibilities of citizenship was regarded as a useless character.” Athenian citizens were more ambitious for glory and power in civic affairs or war than acquiring personal wealth or social status within the private society. Sparta Sparta was the other major city-state that did not go in the direction of Athens with democratic rule, but instead evolved into a form resembling a modern elite dictatorship in various nations of the world. Why did this occur? Their location was more isolated surrounded by mountains, lack of good harbors, and they were economically backward. Sparta resembled early near Eastern monarchies and modern totalitarian regimes. They even had secret police agents among the helots to head off uprisings. There was no middle class that arose to aid the common people and the Spartans’ main endeavor was fighting. Not content to live in the area originally conquered as part of the Dorian invasion in the Dark Ages, the Spartans desired more fertile land. They succeeded in conquering Messenia and annexed the area. An unsuccessful revolt by Messenia led to a tremendous crackdown, and the Spartans murdered or expelled the leaders of the revolt. The rest of the people were turned into slaves called helots. Thereafter, Spartan’s foreign policy was basically defensive. They had two kings, but most of the power was vested in a Board of Governors of five men, called the Ephorate. It 7 controlled all aspects of Spartan society: education, distribution of property, veto power over all legislation, and most egregious was they determined the fate of all newborn infants. If they were sickly or too many were born, then the infants were exposed or thrown off the cliffs. Because of these draconian practices, Sparta eventually became the leading military power in Greece. The Helots or slaves did the farming work as Spartans considered agriculture labor demeaning, while many of the Athenians did some of their own farming. Every Spartan man was allotted land and given state-owned helots to work it. Every year the Spartan Government officially declared war on their helots. This was done not to engage in actual battle, but to justify their treatment of them. As officially at war with the Helots, the Spartans could kill them without a trial. No other polis was like this. Spartan Military, Cultural and Social Customs When the Spartan boys reached seven there were taken from their families to be raised and trained in their age cohort. These young males were never given enough food to satisfy their hunger, so they were encouraged to steal food, and whatever else they needed. Even after Spartan men finished active duty and married, they took their meals with men of the same age instead of with their families. Their fearless courage in war especially against the Persians was legendary. When told the Persians were so numerous at one battle and that Persian arrows would blot out the 8 sun, then one Spartan replied: “Good, we will fight in the shade.” With their long flowing hair and brevity of speech, the Spartans impressed other Greeks as living remnants of the Heroic Age. Life for the Spartans had merits that the adjective Spartan suggests. The English word Spartan means stoic, frugal, and highly disciplined. Spartan citizens were intensely patriotic and dominated most of the states in the Peloponnesus. It is said that they were not addicted to idle talk, and the adjective laconic, name of the Spartan plain was another characteristic of these people. Yet Sparta was undermined by its system, for in the prime of her society in the fifth century B.C.E. it is estimated there were only about four thousand adult male citizens, and its preoccupation with military achievements arrested her cultural development. After the sixth century B.C.E., Sparta contributed almost nothing to Greek greatness in sculpture, architecture, drama, literature, and philosophy. Fear became the foundation of the Spartan state: fear of money, rebellion, defeat by foreign troops, and of foreign ideas. Fear explains their conservatism and their resistance to change. They discouraged outside travel, and even prohibited trade with the outside world. Family and marriage customs of the Spartans were different from the rest of the Greeks too. Husbands carried off their wives on their wedding nights by a show of force. According to the Roman writer, Plutarch, because they saw so little of them afterwards, it sometimes happened that men had 9 children before they ever saw their wives’ faces in daylight. Wives main duty was to produce vigorous offspring. Young maidens engaged in gymnastics and other vigorous sports to achieve the ideal body type for fertility. Wives and mothers were not to lament if their loved ones were killed in war as it was more heroic to die that way than return after losing a war. The soldiers were told to come home “with” your shield or “on” it. Greek Warfare in the Classical Period From 500-338 B.C.E. this period of history is referred to as the Classical Greek period. While many notable creative cultural advances were made, omnipresent war was usually in tandem with these other activities. Warfare was tremendously exciting to the Greeks. Participation in war as in politics was man’s natural occupation. There was a sense of camaraderie in the army. Fighting and winning with their friends developed a psychological high that nothing in peacetime could duplicate. War was considered a confrontation between two willing political communities carried out according to rules of war. A declaration of war was necessary, and made after deliberation of the kings or council and assembly. All Greek citizens engaged in physical exercise for the purpose of keeping fit for battle. The Olympic Games was a natural outgrowth of this. Spartans wore magenta tunics and scarlet cloaks so the blood would not show. The government presented the formal cause of war: self defense, gross impiety, or 10 immorality of the enemy. Most wars saw the final results generally inconclusive. If one side clearly won then the other side had to surrender. This was humiliating and devastating as all citizens’ possessions and property went to the victors, and the women and children became slaves of winners. Sons of citizens all trained in warfare. In most Greek cities, young men eighteen to thirty spent almost all of their time in military activities, but also might be called to participate in war into their sixties. Early Greeks fought with their men in chariots, but in the classical period most of the armies were composed of infantrymen called hoplites. Foot soldiers were a lot cheaper than horses and chariots. Everyone provided their own armor and weapons. They had a round shield, breastplate, bronze helmet that covered the top of the head and much of the face with often a plume or crest on top. Greaves were often worn, but no shoes were worn into battle. The main weapons were the sword, short spear, and longer javelins for throwing. Wealthy men rode horses since they could afford the monetary outlay. As there were no saddles or stirrups riding was difficult in battle, but they served as the military commanders. Naval battles were rare except for the wars against the Persians. At this time Athens was able to dominate the peninsula because her fleet was made up of triremes. Before grappling and boarding operations began, the ship rammed other ships with its metal prow almost like a torpedo. Wars between the Greeks and Persians 11 When the Greek Ionian cities revolted against their Persian rulers in 494 B.C.E, Athens initially intervened to aid them. Initially the Persians were able to subdue all the Greek city-states except Sparta and Athens. With their Royal Road and great supply network, the Persians made use of these advancements. When 100,000 Persians went up against 20,000 Athenians formally at the Battle of Marathon, they were trounced. It is said that the Greek success was due to the phalanx formation eight rows deep. Spartan’s army arrived too late to fight. Not only was this one of the most decisive battles in history, but this battle has been immortalized when a runner from this battle raced to Athens to bring the triumphal news, only to fall dead upon arrival, but the distance of 26.2 miles is now the mileage for the Marathon races world-wide. In 480 B.C.E. Xerxes, the Persian emperor led another massive attack on the Greeks, one at the Pass of Thermopylae, which the Greeks lost, but the Spartans achieved immortality with three hundred hoplites supposedly detaining the Persians long enough for the rest of the Greek army to go on the offensive.3 Athens was defeated then, but in a short time the Athenian navy defeated the Persian navy at the Battle of Salamis. One final battle between the Greeks and Persians in 479 B.C.E. at Plataea, led to the final defeat of the Persians. Herodotus, ( circa 485-425 B.C.E.) who is considered the father of history writing, wrote his History of the Greek and Persian Wars, which became one of the most entertaining 3 Hollywood has immortalized this event in history with its movie 300 12 books ever written as he included the history, customs and beliefs of the Greeks, Persians, Egyptians, and Scythians, bringing to life these cultures. Peloponnesian War When the Persian Wars ended, Sparta and Athens dominated the Greek world. Pericles organized Athens into a confederacy of other Greek city-states, dependent on her naval strength called the Delian League. Meanwhile Sparta was becoming paranoid of Athens’ growing strength and aggressive imperialism. Sparta then formed the Spartan League with her allies, with Sparta supreme on land and Athens on the sea. These two leagues then began the Peloponnesian War that lasted from 431-404 B.C.E. There was extreme brutalization on both sides, and the Greek exiled general and first scientific Historian, Thucydides, produced a great work on this conflict. “My work is not a piece of writing designed to meet the taste of an immediate public, but was done to last forever.” 4 When Persia assisted Sparta she was victorious. Plague devastated Athens in 430 B.C.E., claiming thousands of lives, including Pericles. While the Spartan League officially won the war, both leagues were devastated, and this war would eventually see the downfall of the Greek world when the Macedonian King Philip and then his son Alexander the Great would conquer the Greeks and continue on to victory over the Persians. 4 Thucydides The Peloponnesian War