Week 1 PPT - WordPress.com

advertisement

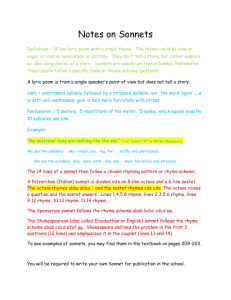

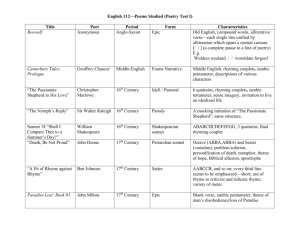

Love Poetry in the 19th Century Isobel Armstrong, Victorian Poetry • ‘ If the poet knows the act of representation is fraught with problems, and if it is not clear to what misprisions the poem might be appropriated, then a structure which analyses precisely the uncertainty, and which makes that uncertainty belong to the struggle and debate, a structure which fills that uncertainty with content, is the surest way to establish poetic form (14). Gordon Braden Petrarchan Love and the Continental Renaissance New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. • ‘the central tenacious fact of his life is his consuming, unending desire for one woman’ p. 14. • ‘What destiny of mine, what compulsion, or what deception brings me unarmed back to the field where I am always conquered? And if I escape from it, I shall marvel; if I die, the loss is mine. Not loss at all, but gain: so sweet in my heart are the sparks and the bright lightning that dazzle and torment it, and in which I take fire and am already burning for the twentieth year’ p. 14. (Canz. 221, 1-8) Gordon Braden Petrarchan Love and the Continental Renaissance New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. • Elsewhere Petrarch writes that ‘the attraction of women, the more fascinating it is, the more dreadful and baleful, to say nothing of their dispositions, than which there is naught more fickle or more inimical to the love of repose’ p. 16. • Petrarch affirms that ‘any ambition for literary success was wholly submerged in the helpless emotional turmoil of this experience’ p. 15. Catherine Bates ‘Desire, Discontent, Parody: The Love Sonnet in Early Modern England’ The Cambridge Companion to the Sonnet • ‘so long as she continues to deny her lover what he says he wants, the identity of that ‘I’ remains affirmed as that of a subject, a subject who desires. This is why the sonnet mistress is usually held at a strategic distance’ p. 107. Gordon Braden • ‘If only that knot which Love ties around my tongue when the excess of light overpowers my mortal sight were loosened, I would take boldness to speak words at that moment so strange that they would make all who heard them weep. But the deep wounds turn my wounded heart forcefully away; I become pale, and my blood hides itself’ p. 19 (Petrarch, Canzioniere 73, lines 79-90) Italian or Petrarchan Sonnet • Divided into octave and sestet. • Octave rhyme scheme abba abba • Change in rhyme for the sestet signifies change in subject: the volta or turn. • Sestet rhyme can have either 2 or 3 rhymes: cdcdcd, cdecde, cddcdc, cdeced, cdcedc. • No couplets to finish English or Shakespearean Sonnet • More flexible rhyme scheme • 3 quatrains and a couplet. • Quatrains divided by rhyme scheme: abab cdcd efef gg • Each quatrain develops a separate idea or metaphor • The turn in subject matter or the volta can be placed after the second or third quatrain W. K. Wimsatt, The Verbal Icon: Studies in the Meaning of Poetry, London: Methuen, 1970. • Rhyme imposes ‘upon the logical pattern of expressed argument a kind of fixative counterpattern of alogical implication’ 153. • ‘The words of a rhyme, with their curious harmony of sound and distinction of sense, are an amalgam of the sensory and the logical, or an arrest and precipitation of the logical in sensory form; they are the icon in which the idea is caught’ 165. Mermin • ‘In Sonnets from the Portuguese, however, the speaker casts herself not only as the poet who loves, speaks, and is traditionally male, but also as the silent, traditionally female beloved.’ P. 352 • Dorothy Mermin, ‘The Female Poet and the Embarrassed Reader: Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnets From the Portuguese’, ELH, Vol. 48, No. 2 (Summer, 1981), pp. 351-367.